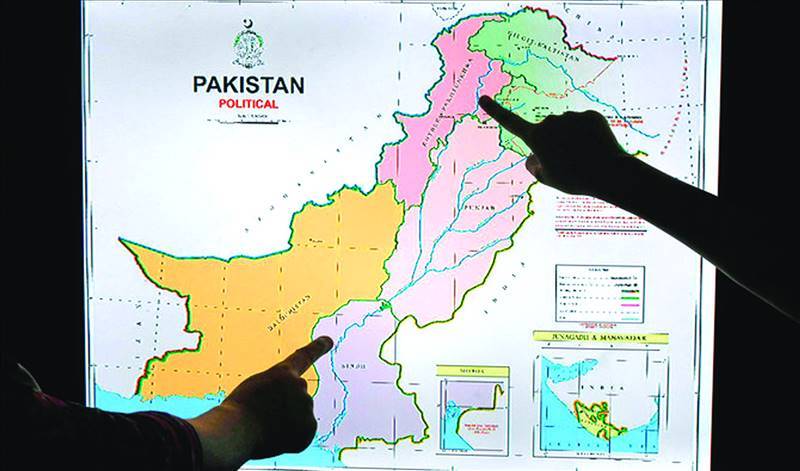

Exactly a year after Prime Minister Modi annulled the special status of Kashmir and annexed the region into the Indian territory, Pakistan responded by unveiling with great fanfare its own new political map.

The new map not only shows the entire Jammu and Kashmir region as Pakistani territory it also lays claims to the Indian regions of Junagadh and Manavadar and highlights Pakistan’s position on Sir Creek: a perfect tit-for-tat to the release last year by India of a political map that showed Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan as its territory.

But is responding in the same coin to every Indian move the correct approach and has it “strengthened our principled stance” on Kashmir as Imran Khan has claimed?

Despite UN resolutions, India has never regarded Kashmir as disputed territory and always considered it as its own. That is why India has claimed that annulment of the special status of Kashmir is in line with its stated policy and ‘a principled stand.’

But what has been Pakistan’s principled stand on Kashmir for the past over 70 years? We have always regarded Kashmir as disputed territory and that its future will be determined by the people of Kashmir themselves and not by anyone else.

If this indeed has been our principled position for decades, how does the new political map advance our principled stand on the disputed territory? How can Islamabad draw a map of the region that it believes is disputed? How can it claim entire Kashmir without even slightest hint that Kashmiri people had been consulted?

The new political map is a new political statement: the people of Kashmir figure nowhere in the calculus of Kashmir dispute, the territory belongs to Pakistan.

It was a grave mistake for Pakistan to make the announcement from its capital Islamabad. In politics optics are important. Any announcement about Kashmir should be seen to have been made by the Kashmiris themselves from their own territory, not by Pakistani officials from Islamabad.

In responding to Indian provocation, Pakistan abandoned its principled stand about who can legitimately decide on the fate of Kashmir.

Pakistan’s Kashmir policy has gone haywire and lost direction. We refuse to do some hard thinking and introspection. Despite publicly acknowledging that Kashmiris alone will determine their fate, we naively assume that the oppressed Kashmiris would want to replace their violent annexation by India with joining Pakistan as one of its federating units. Is there any basis for this wishful assumption?

Has it been debated whether the Kashmiris would really want to be part of the federation of Pakistan which is already at loggerheads with its federating units and people? That, in their desperation to get rid of the Indian occupation army, the Kashmiris would welcome over lordship by another army?

Let us face it: from what is happening inside our own country, the troubles of our own people and of the federating units, Pakistan’s position to be an effective advocate for oppressed Kashmiris has been undermined. It will be no surprise if the new political map only amplifies voices in AJK for independence.

Our responses to various challenges have been knee-jerk and without due deliberations. Releasing Indian air force pilot Abhinandan Varthaman was sensible. But could it not be tied to some quid pro quo instead of designing it to project Prime Minister Imran Khan as a man of peace and deserving of Nobel Peace Prize?

Not opposing India at the time of election to a seat on the UN Security Council was understandable, but what was there to stop Pakistan from highlighting the issue of human rights violations in Indian Kashmir and seek some linkage?

To have a Kashmir Affairs ministry is right, but has a thought ever been given to who heads it? The seriousness of commitment to Kashmir’s cause is brought into question when one sees how ignorant Kashmir Affairs ministers have been about it.

Allowing Afghan transit trade to India was a right decision. But what message was sent out when the next day the Afghan borders at Chaman and other locations along the Pakistan-Afghan borders were closed, thereby nullifying the Afghan transit trade to India?

Implementing the verdict of International Court of Justice (ICJ) in the matter of Indian spy Kulbhushan Jadhav is right, but it did not ask Pakistan to itself file appeal for review and appoint and pay the lawyers for this purpose.

The ICJ verdict provided a great opportunity to the parliament to revisit the seriously flawed military justice system. We did not want the parliament to look into issues in the military justice system. So it was bypassed by issuing an ordinance. It did not matter if it ended up in having to defend Kulbhushan ourselves in the court.

Highlighting enforced disappearances, torture and Indian Kashmir as a vast prison is right. But can our protestations arouse any credibility with the world when citizens and journalists in Pakistan also disappear with impunity and opaque internment centres, the Guantanamo bay prisons operate in former tribal areas without any oversight?

When in power, the army has extended a warm hand of friendship towards India. Zia’s cricket diplomacy and Musharraf’s giving up unilaterally Pakistan’s principled position on UN Kashmir Resolutions readily come to mind. But when it is not in direct power, it demands adopting of a hard line. Remember accusing Shaheed Benazir Bhutto of demolishing the Kashmir House signboard from the route taken by Rajiv Gandhi to please India? Or, the Kargil misadventure soon after Prime Minister Vajpaee visited Lahore at the invitation of Nawaz Shairif? Or, Mumbai mayhem soon after President Zardari offered no first nuclear use talks to India?

It is such inconsistencies in policy that need to be addressed, instead of drawing up new political maps.

The writer is a former senator

The new map not only shows the entire Jammu and Kashmir region as Pakistani territory it also lays claims to the Indian regions of Junagadh and Manavadar and highlights Pakistan’s position on Sir Creek: a perfect tit-for-tat to the release last year by India of a political map that showed Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan as its territory.

But is responding in the same coin to every Indian move the correct approach and has it “strengthened our principled stance” on Kashmir as Imran Khan has claimed?

Despite UN resolutions, India has never regarded Kashmir as disputed territory and always considered it as its own. That is why India has claimed that annulment of the special status of Kashmir is in line with its stated policy and ‘a principled stand.’

But what has been Pakistan’s principled stand on Kashmir for the past over 70 years? We have always regarded Kashmir as disputed territory and that its future will be determined by the people of Kashmir themselves and not by anyone else.

If this indeed has been our principled position for decades, how does the new political map advance our principled stand on the disputed territory? How can Islamabad draw a map of the region that it believes is disputed? How can it claim entire Kashmir without even slightest hint that Kashmiri people had been consulted?

The new political map is a new political statement: the people of Kashmir figure nowhere in the calculus of Kashmir dispute, the territory belongs to Pakistan.

It was a grave mistake for Pakistan to make the announcement from its capital Islamabad. In politics optics are important. Any announcement about Kashmir should be seen to have been made by the Kashmiris themselves from their own territory, not by Pakistani officials from Islamabad.

In responding to Indian provocation, Pakistan abandoned its principled stand about who can legitimately decide on the fate of Kashmir.

Pakistan’s Kashmir policy has gone haywire and lost direction. We refuse to do some hard thinking and introspection. Despite publicly acknowledging that Kashmiris alone will determine their fate, we naively assume that the oppressed Kashmiris would want to replace their violent annexation by India with joining Pakistan as one of its federating units. Is there any basis for this wishful assumption?

Has it been debated whether the Kashmiris would really want to be part of the federation of Pakistan which is already at loggerheads with its federating units and people? That, in their desperation to get rid of the Indian occupation army, the Kashmiris would welcome over lordship by another army?

Let us face it: from what is happening inside our own country, the troubles of our own people and of the federating units, Pakistan’s position to be an effective advocate for oppressed Kashmiris has been undermined. It will be no surprise if the new political map only amplifies voices in AJK for independence.

Our responses to various challenges have been knee-jerk and without due deliberations. Releasing Indian air force pilot Abhinandan Varthaman was sensible. But could it not be tied to some quid pro quo instead of designing it to project Prime Minister Imran Khan as a man of peace and deserving of Nobel Peace Prize?

Not opposing India at the time of election to a seat on the UN Security Council was understandable, but what was there to stop Pakistan from highlighting the issue of human rights violations in Indian Kashmir and seek some linkage?

To have a Kashmir Affairs ministry is right, but has a thought ever been given to who heads it? The seriousness of commitment to Kashmir’s cause is brought into question when one sees how ignorant Kashmir Affairs ministers have been about it.

Allowing Afghan transit trade to India was a right decision. But what message was sent out when the next day the Afghan borders at Chaman and other locations along the Pakistan-Afghan borders were closed, thereby nullifying the Afghan transit trade to India?

Implementing the verdict of International Court of Justice (ICJ) in the matter of Indian spy Kulbhushan Jadhav is right, but it did not ask Pakistan to itself file appeal for review and appoint and pay the lawyers for this purpose.

The ICJ verdict provided a great opportunity to the parliament to revisit the seriously flawed military justice system. We did not want the parliament to look into issues in the military justice system. So it was bypassed by issuing an ordinance. It did not matter if it ended up in having to defend Kulbhushan ourselves in the court.

Highlighting enforced disappearances, torture and Indian Kashmir as a vast prison is right. But can our protestations arouse any credibility with the world when citizens and journalists in Pakistan also disappear with impunity and opaque internment centres, the Guantanamo bay prisons operate in former tribal areas without any oversight?

When in power, the army has extended a warm hand of friendship towards India. Zia’s cricket diplomacy and Musharraf’s giving up unilaterally Pakistan’s principled position on UN Kashmir Resolutions readily come to mind. But when it is not in direct power, it demands adopting of a hard line. Remember accusing Shaheed Benazir Bhutto of demolishing the Kashmir House signboard from the route taken by Rajiv Gandhi to please India? Or, the Kargil misadventure soon after Prime Minister Vajpaee visited Lahore at the invitation of Nawaz Shairif? Or, Mumbai mayhem soon after President Zardari offered no first nuclear use talks to India?

It is such inconsistencies in policy that need to be addressed, instead of drawing up new political maps.

The writer is a former senator