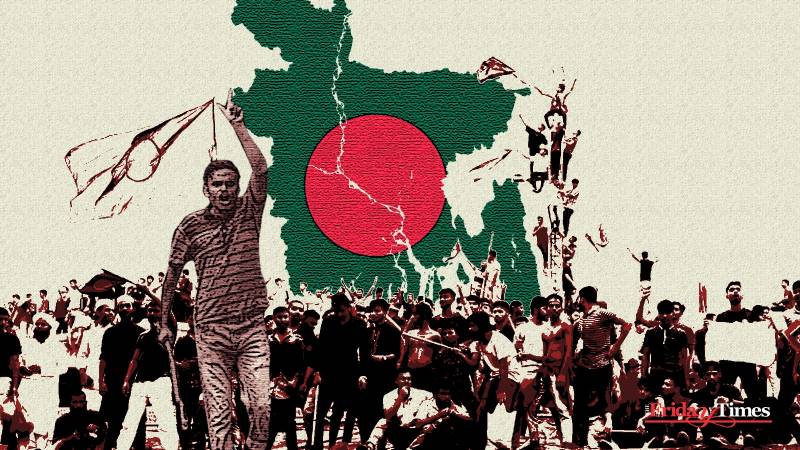

August 5 will go down in history in Bangladesh, akin to a second liberation day, marking the end of Sheikh Hasina’s 15-year authoritarian rule. It was a day when the people seized power, setting aside their differences and uniting in their quest for freedom and a brighter future. How the nation manages this transition will be pivotal in shaping its trajectory as a democracy and a burgeoning economic force in South Asia. The uprising in Bangladesh offers valuable lessons for struggling democracies worldwide.

One, the cost of abrupt, violent change is unaffordable for most nations. Scenes of joy sharply contrast with scenes of destruction and chaos. Victories can lead to looting and destruction. Angry mobs seek revenge and punish both the guilty and the innocent. The breakdown of law after a government’s collapse often harms peace and prosperity. The Bangladeshi people need to envision a future without seeking retribution and vengeance, following the brutality of the Hasina regime and the excitement of their triumph.

Revolutions and power vacuums are very unpredictable. They happen because of economic inequality, political repression, cultural tensions, and public discontent. These things build up over time to overthrow the established order. The specific triggers for a revolution are often impossible to predict, as they can be something as innocent as the public self-immolation of a street vendor or the killing of innocent students.

When a revolution starts, it doesn’t follow a set path. Instead, it is unpredictable and chaotic. Different groups form and vie for power, making the outcome uncertain. Throughout history, we’ve seen that popular uprisings like in Bangladesh can swiftly overthrow stable governments.

The people do not owe their leaders gratitude for simply fulfilling their essential obligations, such as maintaining public order, providing services, and protecting the rights and well-being of citizens. These are the minimum expectations of any competent government, not some generous gesture deserving of endless appreciation.

During revolutions, different groups form and compete for power, creating a chaotic and uncertain outcome that replaces old ways of life with new political and social structures. Their unpredictability makes them both scary and thrilling to witness.

Second, the concept that ordinary people should feel grateful for Hasina’s kindness is flawed and self-serving. Those in power often promote it. Good governance is not a special privilege granted to the masses but a fundamental duty and responsibility of those in authority. The people do not owe their leaders gratitude for simply fulfilling their essential obligations, such as maintaining public order, providing services, and protecting the rights and well-being of citizens. These are the minimum expectations of any competent government, not some generous gesture deserving of endless appreciation.

In reality, those in power, like Hasina, must prove themselves worthy of the public’s trust by demonstrating consistent, ethical, and effective leadership that prioritizes the needs and interests of the people. The public has the power to grant legitimacy to those in authority, and it’s their responsibility to ensure that the governing class fulfills its mandate with diligence, integrity, and a steadfast commitment to the public good. Only then can there be true harmony between the rulers and the ruled, based on mutual accountability and a shared vision for the betterment of society?

Third, while it’s positive that many countries have seen strong economic growth and reduced poverty, these improvements don’t tell the entire story about a nation’s well-being and stability. Even in countries like Bangladesh, which have made good progress in increasing their income and helping many people out of poverty, there are still deep-rooted, systemic problems such as youth unemployment and extremism.

Economic growth is not the only yardstick of progress and development. It is also the extent to which a nation’s citizens have equal access to opportunities, a flourishing democracy, and the essential rights and freedoms that enable them to thrive.

One of the critical issues is the harmful effects of greed and corruption, which can concentrate wealth and power in the hands of a small group of privileged people while leaving most citizens marginalized and without a voice. In addition, the increasing influence of authoritarian rule and the weakening of democratic norms and institutions make life even more challenging for the people.

When intolerant despots like Hasina, elected in flawed democratic processes, gain more control and limit civil liberties, they use the same systems meant to help and protect the people. This harmful cycle, where personal interests and the desire for power take priority over the common good, creates an unstable and unsustainable environment that endangers long-term stability and shared prosperity despite impressive economic figures.

Moreover, economic growth is not the only yardstick of progress and development. It is also the extent to which a nation’s citizens have equal access to opportunities, a flourishing democracy, and the essential rights and freedoms that enable them to thrive. Without addressing these deep-rooted societal problems, even substantial GDP growth is meaningless.

Finally, let us applaud the people of Bangladesh for getting rid of authoritarianism. We are now moving into a new era with hope but also caution. The challenge ahead is to guide the energy of these protests into constructive and meaningful dialogue so that progress benefits everyone, not just a few.