There is a constant debate in Pakistan between the so-called liberals and the more conservative elements that both use — and distort — the message of Mr. Jinnah. The former argue that Jinnah was “secular” by citing his speech to the Constituent Assembly on 11 August 1947. They point to the lines in which Mr. Jinnah said that Pakistanis were free to worship, the Hindus in their temples, the Christians in their churches, and the Muslims in their mosques. The argument assumes that Islam somehow is intolerant of its minorities. That is not the correct Muslim position whatever the realities of Pakistan today. If we are to take the example of the Holy Prophet of Islam (PBUH) himself, the Treaty of Medina guaranteed freedom of worship for the Jews and the Prophet’s (PBUH) letter to St. Catharine’s Monastery in Egypt, guaranteed the same for Christians. Besides, when Lord Mountbatten came down to Karachi to preside over another session of the Constituent Assembly just three days later and proposed that the model for Pakistan should be Akbar, the Mughal Emperor, Jinnah rejected the idea, pointing out that they already had their own role model to inspire them, which was the holy Prophet of Islam. In order to understand Jinnah we need to put both speeches together, and a clear picture of a just, orderly, and compassionate society emerges. He condemned nepotism, provincialism and corruption while emphasizing special care of the poor in society. The Quaid was adamant however that Pakistan would not be a “theocracy.”

Realizing the importance of Mr. Jinnah and in order to understand him better, I had spent most of the decade in the 1990s in conceiving and completing the Jinnah Quartet, which comprised the feature film Jinnah, a documentary film, an academic book and a graphic novel. I received both adulation and vitriol for my efforts. Lies were told in print especially about the Jinnah film (ignoring the detailed audit report which was conducted in 2000 by a British firm – see the Jinnah Film Audit Report which is on-line).

Dr. Mushtaq, a gentle and scholarly man, had written to me that Pakistanis only honor their heroes after they die and he predicted that after my death Pakistanis would love me and name a day in my honor. Before his theory could be tested, I decided it was time to leave.

The situation warrants a long-term and radical strategy to re-establish the writ of the state. It needs to be holistic and long-term. The path ahead will be difficult and will require courage, wisdom and compassion from the leaders of Pakistan.

[quote]Lies were told in print about the film Jinnah[/quote]

The first most vital step is to establish the writ of the state. This can only be done by the reconstitution of a strong, neutral, just, and compassionate civil service, police, and judicial structure in the districts. The elected representatives need to work in tandem with the bureaucracy. The argument that high quality civil servants no longer exist is not correct. Even on this trip I had the privilege of meeting over lunch some of the legendary officers of the old Frontier Province like Omar Khan Afridi and Azam Khan who could be persuaded to advise and guide the service. Even younger officers like Khalid Aziz need to be actively involved in this process. They all agree with my thesis in The Thistle and the Drone that without the reconstruction of a strong political administration and tribal leadership the Tribal Areas will not be stabilized. But the process would not be successful unless the army was withdrawn and the traditional structures were allowed to function. The army needs to change its role in Pakistan’s affairs. Its soldiers are not trained in civil administration but to keep the borders safe. Of course they need to assist bureaucracy when the situation demands. But without the army returning to the barracks, the civil administration will not be able to grow. It is therefore a Catch 22 situation for both.

The army still remains largely intact, its command and control structure in place, in spite of the debilitating and long drawn war on the periphery. The appointment of a charismatic new army chief, General Sharif, has raised hopes among Pakistanis of a leader capable of confronting the challenges that Pakistan faces.

I also noted the energy and vitality in the genuinely free media, in the arts and in literature. There was so much impressive talent in Pakistan. And most important there was a freedom in the air which offset the real challenges of electricity and gas shortages, the high prices and collapsing law and order.

Pakistan must also reach out to its neighbors, especially India and Afghanistan, and convert the prickly relationship to a friendly one – as Mr. Jinnah envisaged. There is so much in common between Pakistan and the two countries in cultural and historical terms that could be built on. Bolder foreign policies on both sides of the border are needed to bring people together. With the population explosion and depletion of resources combined with the collapsing law and order situation in the country, Pakistan simply cannot afford to be entangled in complicated hostile relations with its neighbors.

Pakistani Homecoming

In spite of the gloom and doom of the elite and the law and order situation, my trip to Pakistan went very well. I was overwhelmed by the love and hospitality I received everywhere I went.

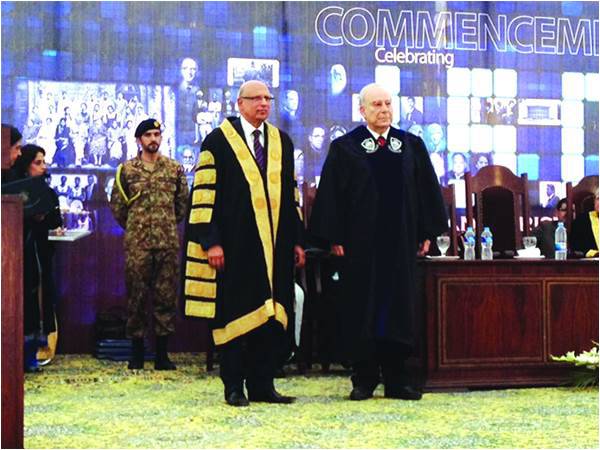

My wife Zeenat and I had flown in to Lahore from Washington, DC at the end of November as guests of Dr. Jim Tebbe, the Rector of Forman Christian College, where I was to receive an honorary Ph.D. at the convocation. The award was given in an impressive ceremony by Mr. Mohammad Sarwar, the Governor of the Punjab. It was a great honor for me and I found the event deeply moving. I felt nostalgic as I wandered about the beautiful Forman campus lost in memories of one of the happiest periods of my life.

Zeenat and I were delighted to be with our daughter Dr. Amineh Hoti and son-in-law Arsallah Khan Hoti in Islamabad and to see how much they were contributing to Pakistan in their own fields. Both were promoting better understanding and better citizenship through notions of insaniat (humanity), ilm (knowledge) and adab (culture). We were privileged and thrilled to be present when Dr. Hoti launched the Center for Dialogue and Action at Forman in Lahore and Arsallah was appointed to the important post of Member of the Privatization Commission.

[quote]Jinnah was adamant that Pakistan would not be a theocracy[/quote]

As a family we were blessed to participate in interfaith bridge building. We visited Nankana Sahib not far from Lahore to pay respects to the birthplace of the great prince of peace Guru Nanak who founded the Sikh faith. We celebrated Christmas with the poorest section of the Christian community living in the midst of the opulence in Islamabad. The Pastor welcomed us to take part in the ceremonies and Dr Hoti spoke beautifully from the pulpit conveying a message of peace and harmony.

I was delighted to be able to reconnect with old friends like Wasim Sajjad, my class fellow from school in Abbottabad and the former president of Pakistan and chairman of the Senate, and Kamal Hyat, my close friend from my Forman College days, and relatives such as Syed Ahmed Masood. Another school friend, former Ambassador Anwar Kemal, lived just outside Islamabad on a farm and generously provided us with a regular supply of the “best” home produced egg in Islamabad.

I also felt privileged to meet some of the most important men of the land, for example Mian Shahbaz Sharif and General Raheel Sharif (no relationship between the two in spite of similar sir names). Chaudhry Shujaat Hussain, the former Prime Minister and another Formanite, treated my family and me with the warm hospitality and affection for which he is famous.

Sartaj Aziz, the elder statesman of Pakistani politics, graciously chaired the book launch of The Thistle and the Drone at the Institute of Strategic Studies Islamabad. Because he is the Foreign Affairs and Security Advisor to the Prime Minister the media was in attendance in full force and next day the headlines were about Mr. Aziz condemning drone strikes in Pakistan.

It is these intelligent, patriotic, and committed Pakistanis — and there are thousands of Pakistanis of this caliber — who are keeping the country functioning and giving it optimism in spite of the chaos around them. I sometimes marvel at the courage of these Pakistanis. I know that most Americans would not be able to live in these conditions with any sense of equanimity and calmness.

I was also able to discuss my ideas at a lunch hosted for me by the Dean of the Ambassadors in Islamabad, the popular Argentinean Ambassador Rodolfo Martin Saravia, who had invited several of his fellow ambassadors.

Senator Mushahid Husain, a high profile public intellectual, invited me to the Senate to address a large gathering of Senators and Parliamentarians from the government and opposition benches in the grand Banqueting Hall of the Senate. Senator Sabir Baloch, Deputy Chair of the Senate, introduced me affectionately in his welcome address by saying that we had met decades ago when I took over as Commissioner of Makran Division, which is his home. He said because I was related to Sir Sayyed Ahmed Khan, I emphasized education and within a week of arrival announced that I would build the first big public school of Makran. When I was told there was no money in the budget, he said with a chuckle, I declared a tax on any Makrani wanting a gun license. With these guns, the Senator recounted, I said you kill each other, and with the school you will be able to educate yourselves.

Through the friendship and bonhomie of the gathering, two themes cropped up which I had heard in many other gatherings: That the United States was bent on destroying Pakistan and that interfaith dialogue was dangerous because it was a conspiracy to “dilute” the purity of Islam. I made the point repeatedly that the suspicion of Americans that so many Pakistanis harbor and their view of Americans as a hostile monolith is a mirror image of what many Americans think of Pakistan – a hostile Islamic population bent on spreading terrorism in the cause of their faith and determined to attack Americans. As for interfaith dialogue, I believe these distinguished Parliamentarians were unaware of Islamophobes in the US like Robert Spencer who argued exactly the opposite that interfaith dialogue was an attempt by Muslim scholars like me to convert Americans to Islam and that Islam was a dangerous and evil religion. Dialogue and bridge-building were the need of the hour. Besides, I pointed out the crisis in Pakistan could only be managed by Pakistanis themselves. The majority of the Senators responded positively to my message of understanding and bridge-building.

I had met, it seemed, everyone there was to meet, appeared on the major television chat shows, and addressed various gatherings, including the top Universities and young Pakistanis in schools, but one thing was still missing, and that was a meeting with a living mystic.

Then on the eve of my departure, my friend and comrade of many decades, Dr. Ghazanfar Mehdi conveyed an invitation from Pir Naqeeb-ur-Rahman of Rawalpindi and his wife for a dinner in my honor at their house. The Pir was a leading Sufi spiritual leader, linked to Zeenat’s direct ancestors like the legendary Akhund of Swat and the Wali of Swat. With his green hat, long flowing hair and talk of universal love, the Pir is a prime target for the Taliban who specifically attack such spiritual leaders as they speak of a universal and inclusive Islam. He is also easily accessible which makes him more vulnerable. As a sign of Islamic duty to the less fortunate, he runs a langar which provides cooked meals round the clock for the poor, who may at any time, without invitation, come and eat.

There was a festive air at the Pir’s large compound that night with strings of bright lights twinkling in different colors. It was an auspicious time: the celebration of the birthday of the Prophet of Islam (PBUH). Sufis in particular celebrate the occasion with great joy and praise the Prophet (PBUH) as a “mercy unto mankind”.

The Pir and his followers were on hand to greet us with honor. Remarkably, the Pir’s wife is an articulate leader for interfaith dialogue among women and has been active in this field with the American Ambassador’s wife. She had also worked with Dr. Hoti and the two were happy to re-connect. As we sat on carpets for dinner, the families joining us, Dr. Mehdi read a beautiful Urdu poem composed by him in honor of the Prophet (PBUH). The Pir then organized the showing of my video poem, “I, Saracen,” on a large screen TV. He appreciated it with kind words and blessed my efforts in building bridges.

This was the perfect ending of my visit to Pakistan, a dinner hosted for me by a leading Pir in which we could celebrate the Prophet’s (PBUH) birthday and talk of the message of peace and compassion for all humanity.

The future would be difficult for Pakistan, but I could see hope. Despite the chaos and mayhem of contemporary Pakistan, there was still wisdom and compassion deep in the soil of Pakistan. This, I thought to myself that night, was after all the land of Data Sahib, Bulleh Shah, Baba Fareed, Rahman Baba and so many other mystics and spiritual leaders throughout Pakistan who advocated faith and peace. Their mystic verses had influenced the great Guru Nanak and his followers invited Mian Mir to lay the foundation stone of their most revered house of worship, the Golden Temple in Amritsar. This land was rich with bridge-builders.

The arc of my visit had been completed. I left Pakistan feeling optimistic.

Akbar S. Ahmed is the Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic Studies at American University, Washington, DC, the former Pakistani High Commissioner to the UK and former member of the Civil Service of Pakistan. His latest book is The Thistle and the Drone: How America’s War on Terror Became a Global War on Tribal Islam (Brookings 2013)

Realizing the importance of Mr. Jinnah and in order to understand him better, I had spent most of the decade in the 1990s in conceiving and completing the Jinnah Quartet, which comprised the feature film Jinnah, a documentary film, an academic book and a graphic novel. I received both adulation and vitriol for my efforts. Lies were told in print especially about the Jinnah film (ignoring the detailed audit report which was conducted in 2000 by a British firm – see the Jinnah Film Audit Report which is on-line).

Dr. Mushtaq, a gentle and scholarly man, had written to me that Pakistanis only honor their heroes after they die and he predicted that after my death Pakistanis would love me and name a day in my honor. Before his theory could be tested, I decided it was time to leave.

The situation warrants a long-term and radical strategy to re-establish the writ of the state. It needs to be holistic and long-term. The path ahead will be difficult and will require courage, wisdom and compassion from the leaders of Pakistan.

[quote]Lies were told in print about the film Jinnah[/quote]

The first most vital step is to establish the writ of the state. This can only be done by the reconstitution of a strong, neutral, just, and compassionate civil service, police, and judicial structure in the districts. The elected representatives need to work in tandem with the bureaucracy. The argument that high quality civil servants no longer exist is not correct. Even on this trip I had the privilege of meeting over lunch some of the legendary officers of the old Frontier Province like Omar Khan Afridi and Azam Khan who could be persuaded to advise and guide the service. Even younger officers like Khalid Aziz need to be actively involved in this process. They all agree with my thesis in The Thistle and the Drone that without the reconstruction of a strong political administration and tribal leadership the Tribal Areas will not be stabilized. But the process would not be successful unless the army was withdrawn and the traditional structures were allowed to function. The army needs to change its role in Pakistan’s affairs. Its soldiers are not trained in civil administration but to keep the borders safe. Of course they need to assist bureaucracy when the situation demands. But without the army returning to the barracks, the civil administration will not be able to grow. It is therefore a Catch 22 situation for both.

The army still remains largely intact, its command and control structure in place, in spite of the debilitating and long drawn war on the periphery. The appointment of a charismatic new army chief, General Sharif, has raised hopes among Pakistanis of a leader capable of confronting the challenges that Pakistan faces.

I also noted the energy and vitality in the genuinely free media, in the arts and in literature. There was so much impressive talent in Pakistan. And most important there was a freedom in the air which offset the real challenges of electricity and gas shortages, the high prices and collapsing law and order.

Pakistan must also reach out to its neighbors, especially India and Afghanistan, and convert the prickly relationship to a friendly one – as Mr. Jinnah envisaged. There is so much in common between Pakistan and the two countries in cultural and historical terms that could be built on. Bolder foreign policies on both sides of the border are needed to bring people together. With the population explosion and depletion of resources combined with the collapsing law and order situation in the country, Pakistan simply cannot afford to be entangled in complicated hostile relations with its neighbors.

Pakistani Homecoming

In spite of the gloom and doom of the elite and the law and order situation, my trip to Pakistan went very well. I was overwhelmed by the love and hospitality I received everywhere I went.

My wife Zeenat and I had flown in to Lahore from Washington, DC at the end of November as guests of Dr. Jim Tebbe, the Rector of Forman Christian College, where I was to receive an honorary Ph.D. at the convocation. The award was given in an impressive ceremony by Mr. Mohammad Sarwar, the Governor of the Punjab. It was a great honor for me and I found the event deeply moving. I felt nostalgic as I wandered about the beautiful Forman campus lost in memories of one of the happiest periods of my life.

Zeenat and I were delighted to be with our daughter Dr. Amineh Hoti and son-in-law Arsallah Khan Hoti in Islamabad and to see how much they were contributing to Pakistan in their own fields. Both were promoting better understanding and better citizenship through notions of insaniat (humanity), ilm (knowledge) and adab (culture). We were privileged and thrilled to be present when Dr. Hoti launched the Center for Dialogue and Action at Forman in Lahore and Arsallah was appointed to the important post of Member of the Privatization Commission.

[quote]Jinnah was adamant that Pakistan would not be a theocracy[/quote]

As a family we were blessed to participate in interfaith bridge building. We visited Nankana Sahib not far from Lahore to pay respects to the birthplace of the great prince of peace Guru Nanak who founded the Sikh faith. We celebrated Christmas with the poorest section of the Christian community living in the midst of the opulence in Islamabad. The Pastor welcomed us to take part in the ceremonies and Dr Hoti spoke beautifully from the pulpit conveying a message of peace and harmony.

I was delighted to be able to reconnect with old friends like Wasim Sajjad, my class fellow from school in Abbottabad and the former president of Pakistan and chairman of the Senate, and Kamal Hyat, my close friend from my Forman College days, and relatives such as Syed Ahmed Masood. Another school friend, former Ambassador Anwar Kemal, lived just outside Islamabad on a farm and generously provided us with a regular supply of the “best” home produced egg in Islamabad.

I also felt privileged to meet some of the most important men of the land, for example Mian Shahbaz Sharif and General Raheel Sharif (no relationship between the two in spite of similar sir names). Chaudhry Shujaat Hussain, the former Prime Minister and another Formanite, treated my family and me with the warm hospitality and affection for which he is famous.

Sartaj Aziz, the elder statesman of Pakistani politics, graciously chaired the book launch of The Thistle and the Drone at the Institute of Strategic Studies Islamabad. Because he is the Foreign Affairs and Security Advisor to the Prime Minister the media was in attendance in full force and next day the headlines were about Mr. Aziz condemning drone strikes in Pakistan.

It is these intelligent, patriotic, and committed Pakistanis — and there are thousands of Pakistanis of this caliber — who are keeping the country functioning and giving it optimism in spite of the chaos around them. I sometimes marvel at the courage of these Pakistanis. I know that most Americans would not be able to live in these conditions with any sense of equanimity and calmness.

I was also able to discuss my ideas at a lunch hosted for me by the Dean of the Ambassadors in Islamabad, the popular Argentinean Ambassador Rodolfo Martin Saravia, who had invited several of his fellow ambassadors.

Senator Mushahid Husain, a high profile public intellectual, invited me to the Senate to address a large gathering of Senators and Parliamentarians from the government and opposition benches in the grand Banqueting Hall of the Senate. Senator Sabir Baloch, Deputy Chair of the Senate, introduced me affectionately in his welcome address by saying that we had met decades ago when I took over as Commissioner of Makran Division, which is his home. He said because I was related to Sir Sayyed Ahmed Khan, I emphasized education and within a week of arrival announced that I would build the first big public school of Makran. When I was told there was no money in the budget, he said with a chuckle, I declared a tax on any Makrani wanting a gun license. With these guns, the Senator recounted, I said you kill each other, and with the school you will be able to educate yourselves.

Through the friendship and bonhomie of the gathering, two themes cropped up which I had heard in many other gatherings: That the United States was bent on destroying Pakistan and that interfaith dialogue was dangerous because it was a conspiracy to “dilute” the purity of Islam. I made the point repeatedly that the suspicion of Americans that so many Pakistanis harbor and their view of Americans as a hostile monolith is a mirror image of what many Americans think of Pakistan – a hostile Islamic population bent on spreading terrorism in the cause of their faith and determined to attack Americans. As for interfaith dialogue, I believe these distinguished Parliamentarians were unaware of Islamophobes in the US like Robert Spencer who argued exactly the opposite that interfaith dialogue was an attempt by Muslim scholars like me to convert Americans to Islam and that Islam was a dangerous and evil religion. Dialogue and bridge-building were the need of the hour. Besides, I pointed out the crisis in Pakistan could only be managed by Pakistanis themselves. The majority of the Senators responded positively to my message of understanding and bridge-building.

I had met, it seemed, everyone there was to meet, appeared on the major television chat shows, and addressed various gatherings, including the top Universities and young Pakistanis in schools, but one thing was still missing, and that was a meeting with a living mystic.

Then on the eve of my departure, my friend and comrade of many decades, Dr. Ghazanfar Mehdi conveyed an invitation from Pir Naqeeb-ur-Rahman of Rawalpindi and his wife for a dinner in my honor at their house. The Pir was a leading Sufi spiritual leader, linked to Zeenat’s direct ancestors like the legendary Akhund of Swat and the Wali of Swat. With his green hat, long flowing hair and talk of universal love, the Pir is a prime target for the Taliban who specifically attack such spiritual leaders as they speak of a universal and inclusive Islam. He is also easily accessible which makes him more vulnerable. As a sign of Islamic duty to the less fortunate, he runs a langar which provides cooked meals round the clock for the poor, who may at any time, without invitation, come and eat.

There was a festive air at the Pir’s large compound that night with strings of bright lights twinkling in different colors. It was an auspicious time: the celebration of the birthday of the Prophet of Islam (PBUH). Sufis in particular celebrate the occasion with great joy and praise the Prophet (PBUH) as a “mercy unto mankind”.

The Pir and his followers were on hand to greet us with honor. Remarkably, the Pir’s wife is an articulate leader for interfaith dialogue among women and has been active in this field with the American Ambassador’s wife. She had also worked with Dr. Hoti and the two were happy to re-connect. As we sat on carpets for dinner, the families joining us, Dr. Mehdi read a beautiful Urdu poem composed by him in honor of the Prophet (PBUH). The Pir then organized the showing of my video poem, “I, Saracen,” on a large screen TV. He appreciated it with kind words and blessed my efforts in building bridges.

This was the perfect ending of my visit to Pakistan, a dinner hosted for me by a leading Pir in which we could celebrate the Prophet’s (PBUH) birthday and talk of the message of peace and compassion for all humanity.

The future would be difficult for Pakistan, but I could see hope. Despite the chaos and mayhem of contemporary Pakistan, there was still wisdom and compassion deep in the soil of Pakistan. This, I thought to myself that night, was after all the land of Data Sahib, Bulleh Shah, Baba Fareed, Rahman Baba and so many other mystics and spiritual leaders throughout Pakistan who advocated faith and peace. Their mystic verses had influenced the great Guru Nanak and his followers invited Mian Mir to lay the foundation stone of their most revered house of worship, the Golden Temple in Amritsar. This land was rich with bridge-builders.

The arc of my visit had been completed. I left Pakistan feeling optimistic.

Akbar S. Ahmed is the Ibn Khaldun Chair of Islamic Studies at American University, Washington, DC, the former Pakistani High Commissioner to the UK and former member of the Civil Service of Pakistan. His latest book is The Thistle and the Drone: How America’s War on Terror Became a Global War on Tribal Islam (Brookings 2013)