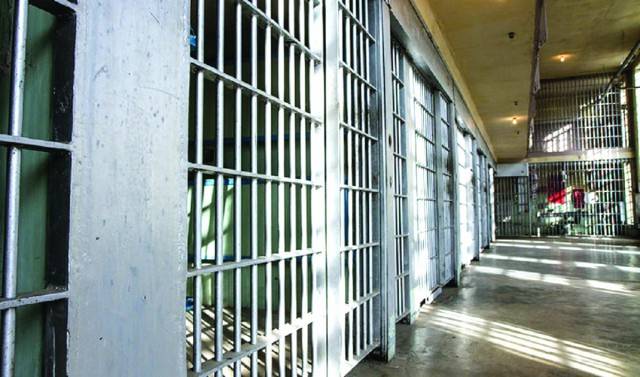

Rukhsana*, a mother of two, was imprisoned in Dhaban Jail in Saudi Arabia for almost five years. She recently returned home to her family on Eidul Azha in 2020.

“I was imprisoned for four years and seven months. I couldn’t be away from my children, not even for a minute. But I said to God, if I am not at fault, then give me my life. And if death comes, let it be when I’m with my children, with my loved ones,” she says. “I was poor and I wanted to see God’s House. But I was betrayed. I was given a box of sweets to take with me. I didn’t know what was really in them. I still cannot understand how or why someone would do such a thing. There are so many women like me in prison. They have little children like me, and just like I came home, I hope God looks over them and brings them back to their homes.”

Over two years ago, on February 18, 2019, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s (KSA) Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman made a gracious gesture. In response to a special request for compassion for Pakistani prisoners by Prime Minister Imran Khan, he promised to return over 2,000 Pakistanis imprisoned in Saudi jails back to their homeland.

This promise, however, remains yet to be fulfilled. According to Justice Project Pakistan, only 89 prisoners had returned by late 2019 since the promise was made. A list of repatriated prisoners submitted to the Lahore High Court by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in December 2019 showed that less than five percent of those who had returned had come back after February 2019. The number of Pakistani citizens still imprisoned in Saudi jails is nearly 2,500.

The holy month of Ramzan is an excellent opportunity to reflect on the principles of forgiveness, mercy and compassion enshrined in Islam. These Pakistani citizens have spent a long time imprisoned in a foreign country, away from their homes, families, and loved ones.

Many of the remaining prisoners are men and women, some of them elderly, deceived into smuggling controlled substances into the Kingdom, under the guise of being sponsored for Umrah or Hajj. They are also often asked to take sweets or fruits with them which, unbeknownst to them, are filled with controlled substances. As soon as these people land in Saudi Arabia, they are immediately arrested and detained. Their families learn of their arrest weeks or months afterwards, once the prisoner is able to call home. According to interviews with detainees and their family members back home, embassy officials rarely visited them or provided any assistance, unlike embassy officials from other countries.

Pakistanis convicted for drug offences are particularly vulnerable to being sentenced to death and likely to be executed in countries that carry out the death penalty. An analysis of 97 executions of Pakistanis carried out in Saudi Arabia and Iran shows that, since January 2016, every nine out of 10 executions have been in relation to drug offences. Research conducted by Justice Project Pakistan also shows that most of these prisoners are victims of weakly regulated recruitment regimes, often deceived and coerced into trafficking drugs.

There has been an increase in the number of Pakistanis on death row abroad and the number of executions carried out globally between 2014 and 2019. Pakistani citizens accounted for 57 per cent of the reported Saudi death-row population and 35 percent of the foreign nationals executed by the Kingdom in 2019.

However, according to a recent report by Harm Reduction International (HRI), confirmed executions for drug offences in Saudi Arabia dropped 94 percent between 2019 and 2020. This is an excellent opportunity for the Kingdom to continue helping prisoners and their families by showing mercy. In the spirit of Ramzan, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia should return the remaining Pakistani prisoners to their homes as soon as possible.

*Name has been changed to protect identity

“I was imprisoned for four years and seven months. I couldn’t be away from my children, not even for a minute. But I said to God, if I am not at fault, then give me my life. And if death comes, let it be when I’m with my children, with my loved ones,” she says. “I was poor and I wanted to see God’s House. But I was betrayed. I was given a box of sweets to take with me. I didn’t know what was really in them. I still cannot understand how or why someone would do such a thing. There are so many women like me in prison. They have little children like me, and just like I came home, I hope God looks over them and brings them back to their homes.”

Over two years ago, on February 18, 2019, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s (KSA) Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman made a gracious gesture. In response to a special request for compassion for Pakistani prisoners by Prime Minister Imran Khan, he promised to return over 2,000 Pakistanis imprisoned in Saudi jails back to their homeland.

This promise, however, remains yet to be fulfilled. According to Justice Project Pakistan, only 89 prisoners had returned by late 2019 since the promise was made. A list of repatriated prisoners submitted to the Lahore High Court by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in December 2019 showed that less than five percent of those who had returned had come back after February 2019. The number of Pakistani citizens still imprisoned in Saudi jails is nearly 2,500.

Many of the remaining prisoners are men and women, some of them elderly, deceived into smuggling controlled substances into the Kingdom,

under the guise of being sponsored

for Umrah or Hajj

The holy month of Ramzan is an excellent opportunity to reflect on the principles of forgiveness, mercy and compassion enshrined in Islam. These Pakistani citizens have spent a long time imprisoned in a foreign country, away from their homes, families, and loved ones.

Many of the remaining prisoners are men and women, some of them elderly, deceived into smuggling controlled substances into the Kingdom, under the guise of being sponsored for Umrah or Hajj. They are also often asked to take sweets or fruits with them which, unbeknownst to them, are filled with controlled substances. As soon as these people land in Saudi Arabia, they are immediately arrested and detained. Their families learn of their arrest weeks or months afterwards, once the prisoner is able to call home. According to interviews with detainees and their family members back home, embassy officials rarely visited them or provided any assistance, unlike embassy officials from other countries.

Pakistanis convicted for drug offences are particularly vulnerable to being sentenced to death and likely to be executed in countries that carry out the death penalty. An analysis of 97 executions of Pakistanis carried out in Saudi Arabia and Iran shows that, since January 2016, every nine out of 10 executions have been in relation to drug offences. Research conducted by Justice Project Pakistan also shows that most of these prisoners are victims of weakly regulated recruitment regimes, often deceived and coerced into trafficking drugs.

There has been an increase in the number of Pakistanis on death row abroad and the number of executions carried out globally between 2014 and 2019. Pakistani citizens accounted for 57 per cent of the reported Saudi death-row population and 35 percent of the foreign nationals executed by the Kingdom in 2019.

However, according to a recent report by Harm Reduction International (HRI), confirmed executions for drug offences in Saudi Arabia dropped 94 percent between 2019 and 2020. This is an excellent opportunity for the Kingdom to continue helping prisoners and their families by showing mercy. In the spirit of Ramzan, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia should return the remaining Pakistani prisoners to their homes as soon as possible.

*Name has been changed to protect identity