On a day when you have over-worked yourself, there is nothing more indulgent than coming home and switching on a sitcom as a panacea for stress. Of the shows that are currently dominating the air space, two that take my fancy are Outsourced and Citizen Khan. Both are hilarious, but where one is positively hilarious, the other can be offensively so.

Outsourced airs on NBC (USA), Global (Canada), Universal (Singapore, Indonesia, Thailand, Honk Kong), Comedy Central (Pakistan, Bangladesh, India and Sri Lanka) and other countries in the Middle East, Australia, and across the rest of the world. Populated with an almost all Indian-descent cast, it is set in a business call-centre in Mumbai, India, where a single good-looking young American, Todd Dempsy (Ben Rappaport), heads the company with a diverse group of male and female employees. It depicts the Indian workplace as friendly and fun, if a little innocently “bungal-wala” type. Todd Dempsy’s job is to explain American popular culture to the employees while trying to comprehend the complexities of Indian culture. Attractive as the more alluring bits of Indian culture are, the actors discuss saris, the colours of India, Diwali—all this playing into the glamourous image of India that has been painstakingly and successfully constructed over the past decades.

Outsourced works well as a comedy because it plays up human elements deftly – romance, mistakes, the challenges of everyday work and life and the friction and attractions between people working together – creating a heady flavour of India that could stimulate the appetite of any viewer around the world to go and visit the vast Indian land of elephants, colour, and multiple cultures.

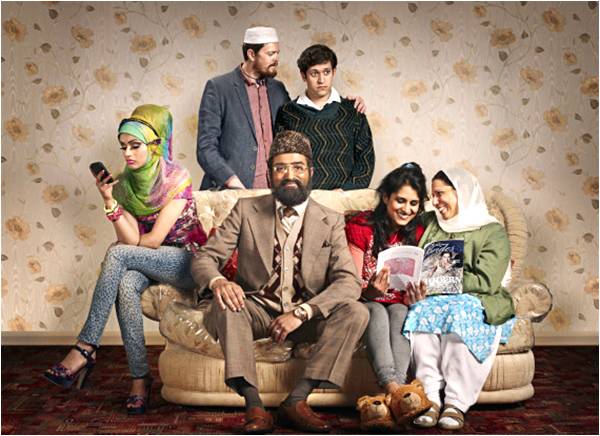

Immediately after Outsourced, Comedy Central shows Citizen Khan (produced by the BBC). As a Pakistani it leaves you fidgeting in your seat. In complete contrast to Outsourced, yet parallel to it, the show revolves around the central character of Mr. Khan with a heavy desi accent, who is a patriarchal self-appointed community leader in the local mosque in Sparkhill, Birmingham, UK. Citizen Khan – and here is the catch – is played by an almost all-Indian cast and developed and written by Anil Gupta and played by British-Pakistani Adil Ray. Mr Khan has a straggly beard and a Jinnah topi with a brown suit that is just a little too small on him, as if it had shrunk in the washing machine. He lives in a terraced house with two daughters, Shazia and Alia (played by Maya Sondhi and Bhavna Limbachia) and a long-suffering wife (played by Shobu Kapoor) who is always moaning and groaning. One daughter comes across as a genuine, simple and nice person but because she doesn’t wear the hijab she is not Mr. Khan’s favourite. The other has full makeup on, wears tight clothes, and sneaks out of her house to see her male friends, but because she wears the hijab she is the favoured daughter. Mr. Khan’s house is gaudy with garish wallpaper—in “paindu-style” the sofas are covered with plastic to protect them from dirt – all of which leaves us with the impression of a man who is unsophisticated and a bit crude. He invites a philanthropist to the mosque, but when an Englishwoman arrives just before the mosque committee does, he throws her out of the window in panic!

These two shows can be taken as a reflection of the different audiences they address and from the different cultures they emanate.

Outsourced as representative of American humour that, in this case, romanticizes the orient while blurring the image of the perceived “other”, whereas British humour is more slapstick, like Shakespeare’s plays: throwing people out of the window and laughing at oneself part and parcel of being British.

But more interestingly these two shows depict the different stereotypes associated with Indian and Pakistani cultures and the manner in which the two countries are currently perceived in the West. In Outsourced we see an ‘India shining’, an India shoulder to shoulder with America, able to outsource its goods. Even if the characters are caricaturized from time to time, they are also allowed to be seen as full people whose culture, even if depicted in a romantically Orientalist manner has aspects worth celebrating and emulating. Citizen Khan, on the other hand, seems to perpetuate tired old stereotypes about Pakistani families, serving to reinforce the image of a backward Pakistan and a forward looking India. Even then, the small mercy of it not depicting them as terrorists might be reason enough for most Pakistanis to embrace the show.

But to expect the British or the Americans to depict Pakistan or Pakistani characters in a nuanced fashion is reminiscent of a colonial hangup. It is Pakistanis themselves who need to create and showcase the vast array of Pakistaniness that occupies a large arc of the human spectrum. We have many issues on which a happy, “halal” comedy can be based. So while Citizen Khan may be an archaic and limited depiction of a Pakistani household, at least it is a depiction. And one that mercifully relies on comic tropes rather than those of violence to depict a ‘backward’ Pakistaniness. It is we ourselves who need to springboard from there and create depcitions of a Pakistan that our current television plays absolutely refuse to acknowledge, a Pakistan of humour, compassion, self-deprecation and irony.

Outsourced airs on NBC (USA), Global (Canada), Universal (Singapore, Indonesia, Thailand, Honk Kong), Comedy Central (Pakistan, Bangladesh, India and Sri Lanka) and other countries in the Middle East, Australia, and across the rest of the world. Populated with an almost all Indian-descent cast, it is set in a business call-centre in Mumbai, India, where a single good-looking young American, Todd Dempsy (Ben Rappaport), heads the company with a diverse group of male and female employees. It depicts the Indian workplace as friendly and fun, if a little innocently “bungal-wala” type. Todd Dempsy’s job is to explain American popular culture to the employees while trying to comprehend the complexities of Indian culture. Attractive as the more alluring bits of Indian culture are, the actors discuss saris, the colours of India, Diwali—all this playing into the glamourous image of India that has been painstakingly and successfully constructed over the past decades.

Outsourced works well as a comedy because it plays up human elements deftly – romance, mistakes, the challenges of everyday work and life and the friction and attractions between people working together – creating a heady flavour of India that could stimulate the appetite of any viewer around the world to go and visit the vast Indian land of elephants, colour, and multiple cultures.

Immediately after Outsourced, Comedy Central shows Citizen Khan (produced by the BBC). As a Pakistani it leaves you fidgeting in your seat. In complete contrast to Outsourced, yet parallel to it, the show revolves around the central character of Mr. Khan with a heavy desi accent, who is a patriarchal self-appointed community leader in the local mosque in Sparkhill, Birmingham, UK. Citizen Khan – and here is the catch – is played by an almost all-Indian cast and developed and written by Anil Gupta and played by British-Pakistani Adil Ray. Mr Khan has a straggly beard and a Jinnah topi with a brown suit that is just a little too small on him, as if it had shrunk in the washing machine. He lives in a terraced house with two daughters, Shazia and Alia (played by Maya Sondhi and Bhavna Limbachia) and a long-suffering wife (played by Shobu Kapoor) who is always moaning and groaning. One daughter comes across as a genuine, simple and nice person but because she doesn’t wear the hijab she is not Mr. Khan’s favourite. The other has full makeup on, wears tight clothes, and sneaks out of her house to see her male friends, but because she wears the hijab she is the favoured daughter. Mr. Khan’s house is gaudy with garish wallpaper—in “paindu-style” the sofas are covered with plastic to protect them from dirt – all of which leaves us with the impression of a man who is unsophisticated and a bit crude. He invites a philanthropist to the mosque, but when an Englishwoman arrives just before the mosque committee does, he throws her out of the window in panic!

These two shows can be taken as a reflection of the different audiences they address and from the different cultures they emanate.

Outsourced as representative of American humour that, in this case, romanticizes the orient while blurring the image of the perceived “other”, whereas British humour is more slapstick, like Shakespeare’s plays: throwing people out of the window and laughing at oneself part and parcel of being British.

Citizen Khan seems to perpetuate tired old stereotypes about Pakistani families

But more interestingly these two shows depict the different stereotypes associated with Indian and Pakistani cultures and the manner in which the two countries are currently perceived in the West. In Outsourced we see an ‘India shining’, an India shoulder to shoulder with America, able to outsource its goods. Even if the characters are caricaturized from time to time, they are also allowed to be seen as full people whose culture, even if depicted in a romantically Orientalist manner has aspects worth celebrating and emulating. Citizen Khan, on the other hand, seems to perpetuate tired old stereotypes about Pakistani families, serving to reinforce the image of a backward Pakistan and a forward looking India. Even then, the small mercy of it not depicting them as terrorists might be reason enough for most Pakistanis to embrace the show.

But to expect the British or the Americans to depict Pakistan or Pakistani characters in a nuanced fashion is reminiscent of a colonial hangup. It is Pakistanis themselves who need to create and showcase the vast array of Pakistaniness that occupies a large arc of the human spectrum. We have many issues on which a happy, “halal” comedy can be based. So while Citizen Khan may be an archaic and limited depiction of a Pakistani household, at least it is a depiction. And one that mercifully relies on comic tropes rather than those of violence to depict a ‘backward’ Pakistaniness. It is we ourselves who need to springboard from there and create depcitions of a Pakistan that our current television plays absolutely refuse to acknowledge, a Pakistan of humour, compassion, self-deprecation and irony.