In a previous article, the authors detailed how South Asia experiences some of the worst air quality in the world, which poses a significant risk to human health. In Lahore—Pakistan’s second most populous city and the capital of Punjab province—reducing particulate matter (PM2.5) levels to the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) standards would lead an average resident to gain 7.5 life years. To increase awareness, several cities have attempted to provide residents with air quality data, but it remains unreliable and inaccessible to a vast majority.

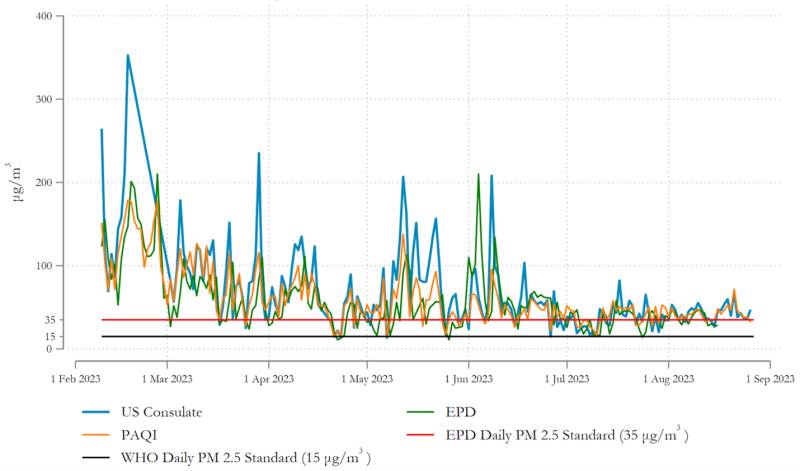

Comparing Lahore’s daily PM2.5 levels from February – August 2023 from three different sources along with the local Environmental Protection Department’s (EPD’s) daily PM2.5 mandated standard shows how far the levels are from the WHO’s daily PM2.5 recommended safe standard. The trends reveal that Lahore’s air pollution levels exceeded the mandated and recommended safe standards almost throughout the six-month period. On an overwhelming majority of days, pollution levels remained considerably higher than the standards.

Recent evidence demonstrates that residents of developing cities exhibit a substantial willingness to pay for air pollution information—specifically, pollution forecasts. Residents are willing to pay, on average, 60 percent of the cost of 4G internet services to receive pollution forecasts through SMS for three months. Consuming pollution forecasts further increases demand for avoidance goods such as particulate filtering masks and improves the alignment of outdoor time with actual pollution levels. Thus, scaling air pollution information within cities can yield large public benefits.

Daily PM2.5 levels in Lahore from 3 sources, compared to the EPD’s daily PM2.5 mandated standard (red horizontal line) and the WHO’s daily PM2.5 daily recommended safe standard (black horizontal line)

Providing air quality data can be challenging

Governments in developing countries, however, struggle to consistently provide air quality readings. Often, a lack of resources and capacity inhibits governments’ ability to maintain the infrastructure for gathering and disseminating information. Governments also perversely withhold information to obscure the true extent of air quality deterioration.

If the person believes that the public sources’ quality is lower relative to the private source’s quality, they may exhibit a lower willingness to pay for the public forecasts.

To fill the data void created by governments, several private initiatives have sprung up, offering residents alternative sources of air quality information. In Lahore, the Pakistan Air Quality Initiative (PAQI)—a private citizens group—crowd-sources low-cost air pollution monitors across the city, reporting hourly readings on Twitter and a mobile app at no charge.

Private sources such as the PAQI may improve access to air quality information, but their efficacy depends on how accurate citizens find the information and how these citizens’ beliefs on accuracy shape which sources they prefer. Given competing information sources, we don’t know whether actual service quality or beliefs about the sources’ quality drive the demand for such information.

For example, suppose a person wants air pollution forecasts and must choose between a public source and a private source to receive them. The sources’ forecast quality is identical, but the person does not know this facet. If the person believes that the public sources’ quality is lower relative to the private source’s quality, they may exhibit a lower willingness to pay for the public forecasts.

What we ask and how we answer our questions

Our research studies developing city citizens’ beliefs about and demand for air quality information. We ask the following broad questions: are citizens willing to pay for air quality information regardless of its source? Does willingness to pay for air quality information vary by source? Does the source affect beliefs about service quality and the state of air pollution? Does exposure change preferences for sources?

To answer our questions, we conducted a randomized controlled trial with roughly 1,000 residents of a lower-middle-income neighborhood in Lahore, Pakistan. We first developed a forecast model of day-ahead air pollution using data from both government and private sources. We then provided the forecasts through SMS to all our respondents daily for two months. But we randomized the disclosed source of information—in one treatment arm, we informed respondents that we constructed the forecasts using a government source (Environmental Protection Department Punjab [EPD]), while in the other treatment arm, we informed respondents that we constructed the forecasts using data from a private source (PAQI). Thus, we provided respondents with identical forecasts while varying the attributable information source.

We elicit four (primary) outcomes: 1) willingness to pay for air pollution forecasts; 2) beliefs about the next day’s air pollution level; 3) beliefs about the accuracy of our forecasts; and 4) willingness to donate to government and private agencies. To elicit truthful responses, we incentivized the four outcomes.

What do we find?

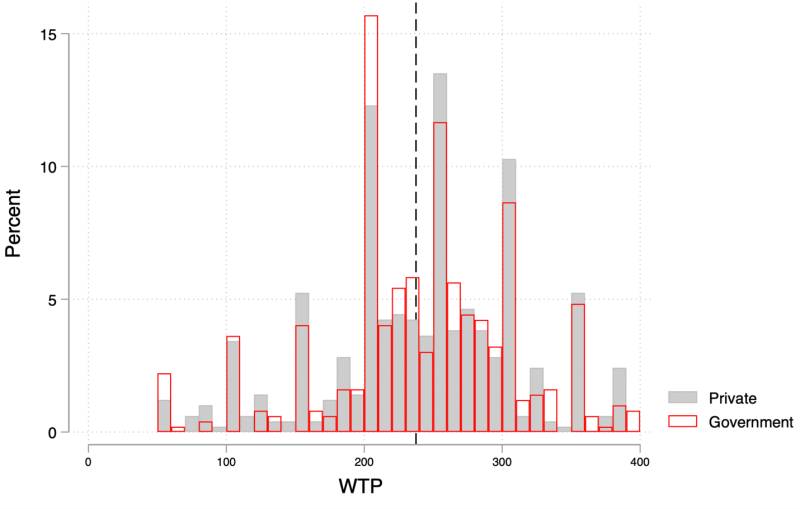

First, residents of developing cities value air pollution information—this corroborates what we knew before. We find that our respondents—residents of a working-class neighborhood of Lahore—are willing to pay Pakistani Rupees (PKR) 238 on average to continue receiving air pollution forecasts for another two months. This amount roughly translates into the cost of monthly prepaid mobile and data services. Thus, scaling the service across the city—with close to 14 million residents—will lead to large public benefits.

Investing in pollution monitoring and forecasting would considerably enhance public welfare—the benefits within cities dwarf the costs.

Second, the source of information doesn’t matter. We do not find evidence that telling respondents that the forecasts they receive stem from a government source or a private source leads to differences in willingness to pay for the forecasts. Respondents are satisfied with the forecast service regardless of the source.

Third, the source of information doesn’t change respondents’ beliefs about air pollution levels, but it does slightly shift beliefs about the accuracy of the forecasts. Respondents who receive forecasts attributed to the government expect a 12 percent higher error in the forecast relative to the private arm. Thus, respondents in the government arm believe that the government provides lower-quality service yet are willing to pay as much for the service as those in the private arm.

The willingness to pay (WTP) for air pollution forecasts

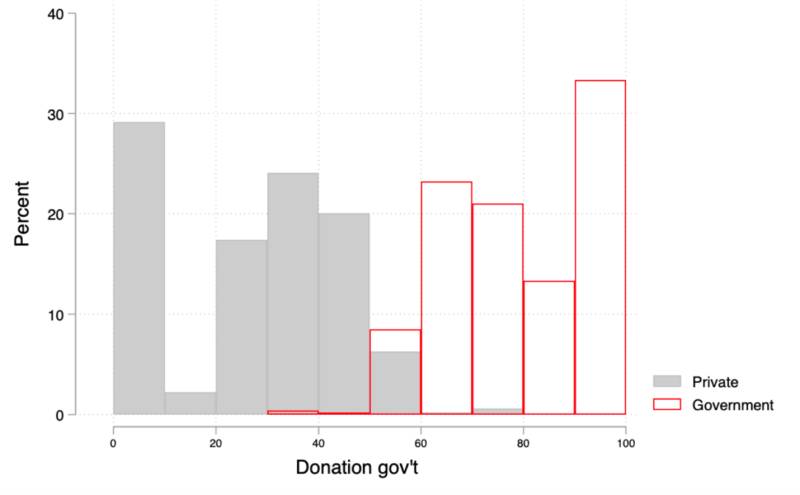

Fourth, recipients prefer the source that we assign to them. In a baseline survey conducted before we started the forecast service, most respondents equally split an endowment of PKR 100 between the EPD (government source) and the PAQI (private source). However, after receiving the forecasts for two months, the respondents split the endowment roughly 75:25 in favor of the source that we assign to them. Thus, citizens’ preferences for air quality sources are relatively malleable.

Donation to government vs private source of air quality information: how respondents within each treatment arm allocate a PKR 100 endowment to the EPD. The grey bars represent respondents who receive forecasts attributed to the PAQI (private source). The red bars represent respondents who receive forecasts attributed to the EPD (government source).

Policy takeaways

Our work demonstrates that developing-city citizens value air pollution information, exhibiting considerable demand for pollution forecasts even when this information isn’t broadly available. Investing in pollution monitoring and forecasting would considerably enhance public welfare—the benefits within cities dwarf the costs.

We also find that the source of information doesn’t change citizens’ demand for it. Those who receive government data value it as much as those who receive private data. Policymakers can leverage private sources to scale up the provision of air quality information, complementing the government’s own data.

Our findings also point to opportunities for private firms to sell air quality information in developing country markets.

This blog is based on our recent ICG report—titled “Beliefs, signal quality, and information sources: Experimental evidence on air quality in Pakistan.” The International Growth Center (IGC) generously supported this work