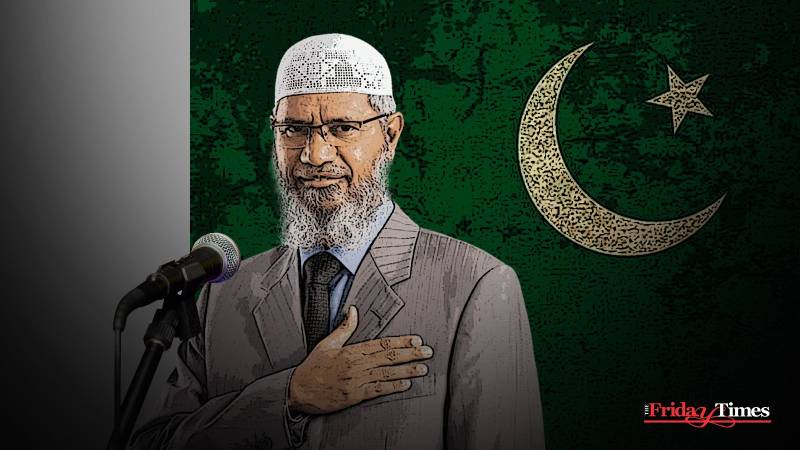

The announcement that Dr Zakir Naik’s would be visiting Pakistan ignited a wave of mixed reactions. For some, it was welcomed as a visit by a scholar renowned for his mastery of interfaith dialogue and comparative religion, who had inspired numerous non-Muslims to embrace Islam. For others, it was an unnecessary gesture to invite a televangelist to Pakistan, a country where 96% of the population is Muslim. Do Muslims, already in the overwhelming majority, need to become more devout? Or is there an underlying presumption that the faith they practice lacks some essential element of true Islam?

More concerning was the nature of his visit as a state guest. When a foreigner accepts an invitation from a political government to be hosted as a state guest, their visit inevitably assumes a political dimension, leaving them open to political scrutiny and criticism, whether they are a religious scholar or otherwise.

Dr Naik appeared ill-prepared for such a reception, and even less so for the rigorous questions that tested his religious knowledge on public forums across Pakistan. The first of these encounters took place at the Governor’s House in Karachi, where a young woman asked about the blasphemy laws in the context of societal intolerance. Dr Naik promptly sidestepped the question, stating that he preferred to first take questions from non-Muslims. In response, a Christian from Sindh province raised concerns about the public rebuke and social discrimination he faced due to his faith. Once again, Dr Naik evaded a direct response. It seemed that these topics were either not his preferred areas of discussion or perhaps his state hosts had advised him to steer clear of such contentious issues.

However, the most revealing moment of the visit was yet to come. And indeed, it arrived during his public appearance in Karachi.

It was a Pashtun girl who posed a poignant question about the society in which she lived – a society where Islam is, in many ways, practiced in the strict manner that a devout mindset might favour. Women do not leave their homes unnecessarily, they are fully veiled when they do venture out, and men are diligent in attending the mosque, and so on. Yet, within this so-called Islamic society, adultery, pedophilia, and other social vices are rampant. Why?

What prompted the Pakistani authorities to extend an invitation to such a controversial figure as a state guest, especially given the poor display of his knowledge of Islam at the public gathering in Karachi? How does this serve an already divided society, fractured along religious and ethnic lines? More importantly, how does it benefit Pakistan?

Dr Naik, rather surprisingly, took issue with both the question and the girl herself. According to him, her question was self-contradictory because she referred to a society with such vices as 'Islamic.' He even went so far as to suggest that if she were to raise this question before God, she would be in trouble.

It was clear, however, that her intent was to highlight that enforcing practices such as keeping women indoors, making them observe purdah, and frequent mosque attendance does not necessarily ensure a virtuous Islamic society or even one with basic decency and moral integrity. Her question demanded a philosophical discourse, yet Dr Naik reduced it to a matter of semantics – mere wordplay. He even presumed to read God’s mind, positioning himself as a divine spokesperson, speculating on how God would respond to her query. To put it mildly, Dr Naik's approach to the question was dismissive, rude, and entirely inadequate.

It further raises questions about the wisdom of inviting someone like Dr Naik as a state guest, particularly when his entry is banned in countries such as the UK, USA, Canada, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka. He is also prohibited from delivering public speeches in many Gulf countries. So, what prompted the Pakistani authorities to extend an invitation to such a controversial figure as a state guest, especially given the poor display of his knowledge of Islam at the public gathering in Karachi? How does this serve an already divided society, fractured along religious and ethnic lines? More importantly, how does it benefit Pakistan?

Dr Naik was received by the Speaker of the National Assembly, the Prime Minister, and several members of his cabinet, as well as other government officials. These meetings were prominently featured on national television. However, his visit to Maulana Fazlur Rehman was of particular interest. It was a far more subdued affair, with Dr Naik meeting only Maulana’s inner circle. He was not invited to address the students from the 25,000 madrasas run by the Maulana, despite their shared Deobandi affiliation. As a seasoned politician, Maulana likely recognised the political undertones of Dr Naik’s visit and opted to downplay the significance of their meeting.

There were rumours circulating upon the announcement of Dr Naik’s visit that the intention behind his invitation was to distract the public from the contentious 26th Amendment, which the government was attempting to pass through parliament without having the required votes. There were also whispers within political circles that Dr Naik was preparing the ground for the introduction of some form of Khilafat – a rule of absolute authority – which the proposed 26th Amendment allegedly sought to establish. While such speculation may be mere hearsay, it undoubtedly contributed to the controversy surrounding his visit. Some even suggested that his presence was intended to undermine and overshadow the rallies and protests of the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI).

Regardless of the true intentions behind inviting the televangelist, one critical aspect of his visit appears to have been entirely overlooked: How will the world perceive Pakistan for hosting a controversial religious figure whose entry is banned in several countries, including the United States, on whom Pakistan heavily relies for its economic and defence needs? Not to mention the much-needed IMF bailout package that the government and establishment have secured with great difficulty. Now, consider this visit in the context of the ongoing developments in the Middle East and Pakistan’s precarious position as a nation teetering on the edge of economic collapse. What message is being sent out? And how prepared is Pakistan for a potentially strong response from its international donors?

Dr Naik will conclude his visit in the coming days. The 26th Amendment may never pass, and even if it does, it will not undo the damage that this televangelist’s visit has inflicted on our society and, undoubtedly, on how the world will perceive us—as an extremist nation. A reflection of this might be seen during the upcoming Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) annual conference, to be held in Islamabad on October 15, where the Indian External Affairs Minister may seize the opportunity to launch further criticism.