The arrival of a niece from Karachi, who’s an English major, gave us the impetus to visit Tao House, which is only a 15-minute drive from our house. But it’s one of those attractions that the mind dismisses as being “too close to merit a visit,” even though it is maintained by the US National Park Service and attracts visitors from around the globe.

We had visited it years ago but did not remember much about the house. This time we were greeted by a tour guide who was not only knowledgeable about the architecture of the house but equally knowledgeable about O’Neill’s contribution to literature. She made O’Neill come alive.

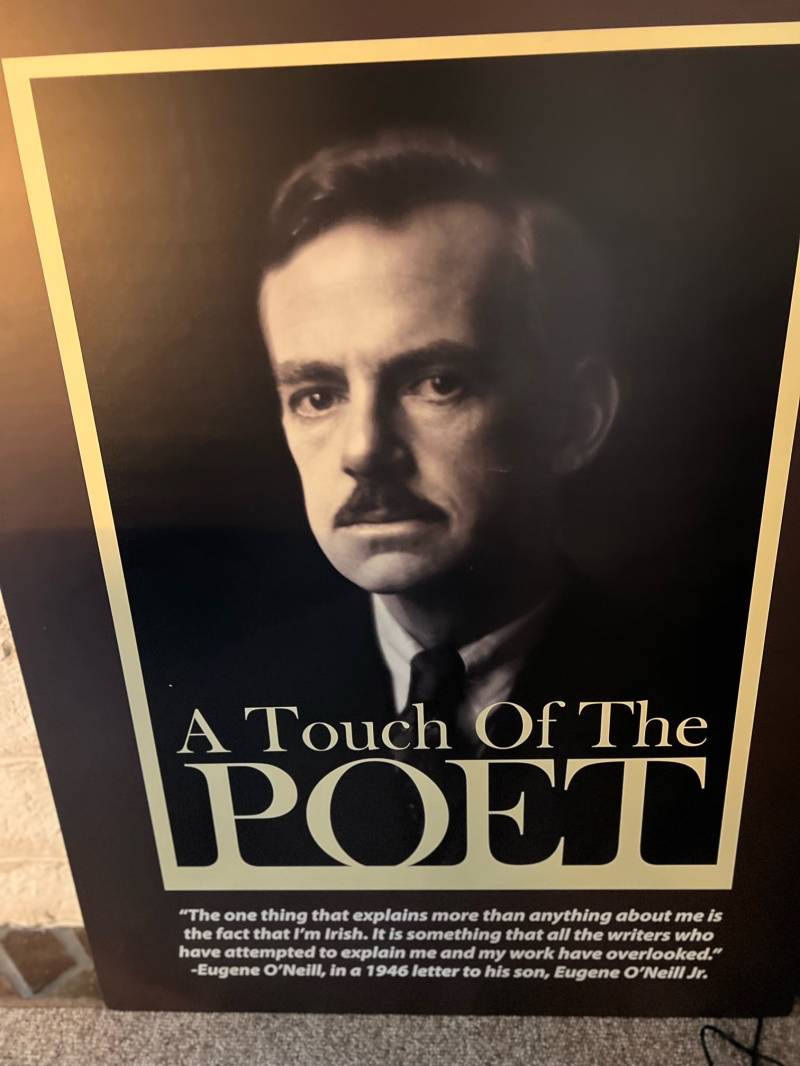

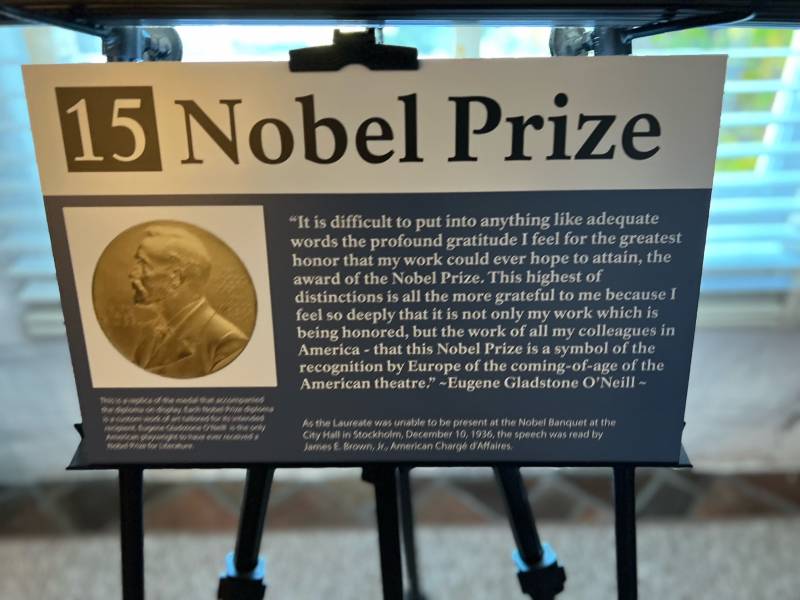

O’Neill is the only American playwright to get a Nobel Prize in Literature. His most famous play, Long Day’s Journey into the Night, was written here, between 1937 to 1944. After leaving Tao House, he never wrote another play. He had won three Pulitzer Prizes before being awarded the Nobel and would win a fourth after the Nobel.

He was born in a small town in Connecticut to Irish American parents. His father was a stage actor who performed The Count of Monte Cristo several thousand times. O’Neill studied at Princeton University but for reasons that are murky, quit after a year. He joined the merchant marine and relished being a sailor. But an illness forced him to quit and that’s when he turned to art.

He was plagued with depression and turned to alcohol, but it was only when he quit alcohol that he wrote his best plays. At some point, he developed tuberculosis and had to live in a sanitarium. Later, he developed Parkinson’s. What killed him in the end was a rare disorder of the brain.

They named it Tao House, reflecting Eugene’s interest in Asian philosophy and Carlotta’s interest in style. The architecture exudes Taoism

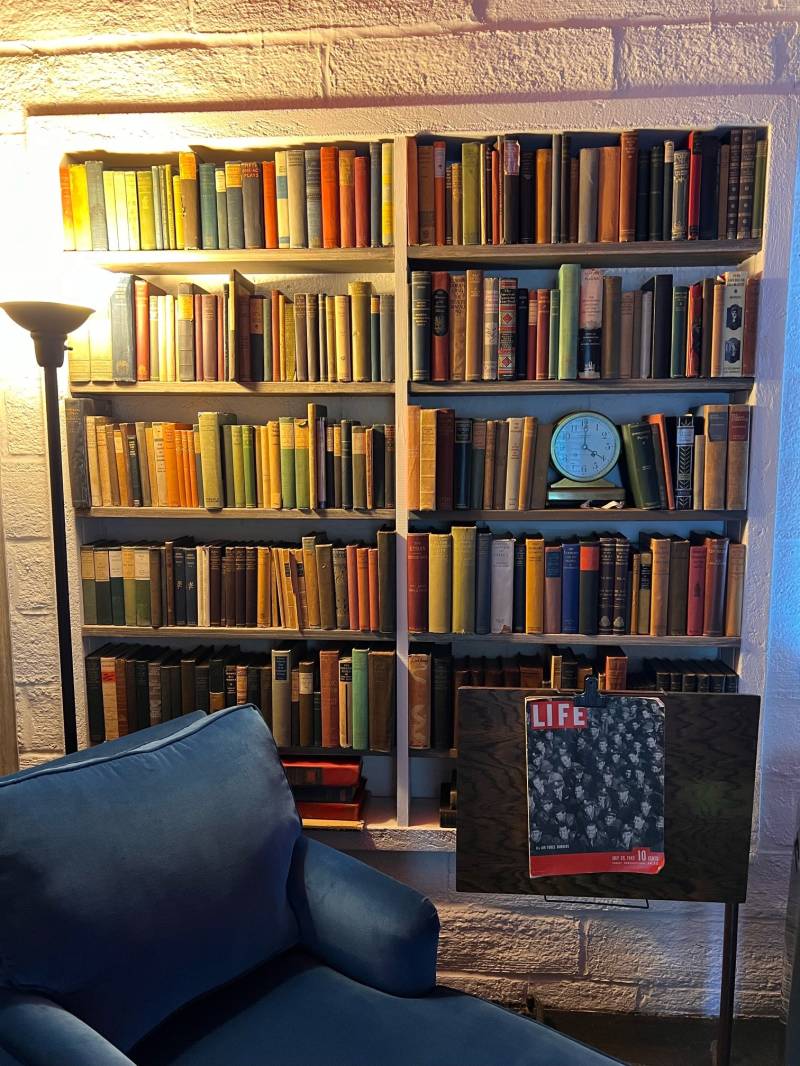

A voracious reader since the age of seven, he wrote fifty plays. After being awarded the Nobel Prize in November 1936, Eugene and his third wife, Carlotta, used the prize money to get away from the hustle and bustle of the East Coast and build a retreat in the Las Trampas Hills that lie some 45 miles east of San Francisco. They bought 158 acres of a ranch and built a house on it.

They named it Tao House, reflecting Eugene’s interest in Asian philosophy and Carlotta’s interest in style. The architecture exudes Taoism. There are heavy basalt brick walls, a roof of black colored tiles, and doors that open out to several porches and patios. Inside, the dark blue ceilings and colored mirrors provide the chic look Carlotta wanted. The fireplace contains two Chinese characters, and the railings of the stairs that go up to the second floor have wooden lions carved at the ends.

The house offers sweeping views of Mt. Diablo, which is nearly 4,000 ft tall, and of the surrounding valleys. From his study, O’Neill could see the oak-studded hills in the west and walnut and fruit orchards in the east. To the north, he could see the waters of the Carquinez Strait. In 1937, he wrote to a friend: “We have a beautiful site in the hills of the San Ramon Valley with one of the most beautiful views I’ve ever seen. This is the final home and harbor for me. I love California. Moreover, the climate is one I know I can work and keep healthy in. Coastal Georgia was no place for me.”

On the grounds is a swimming pool, which O’Neill used often, and the grave of O’Neill’s dog, to whom he was so attached that he even wrote its Last Will and Testament. The dog was often found roaming the streets of the town at the bottom of the hills.

O’Neill did not get along with his children. When his daughter married Charlie Chaplin, he disowned her, perhaps because of their age difference. He and Carlotta quarreled several times over the years. They often lived away from each other but never divorced.

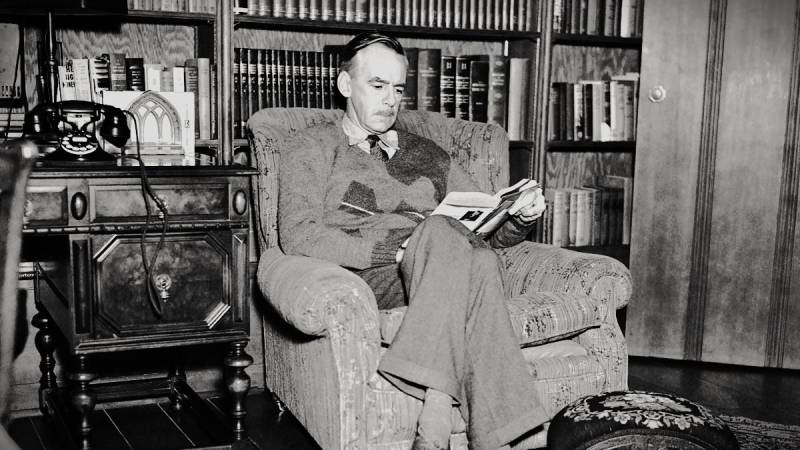

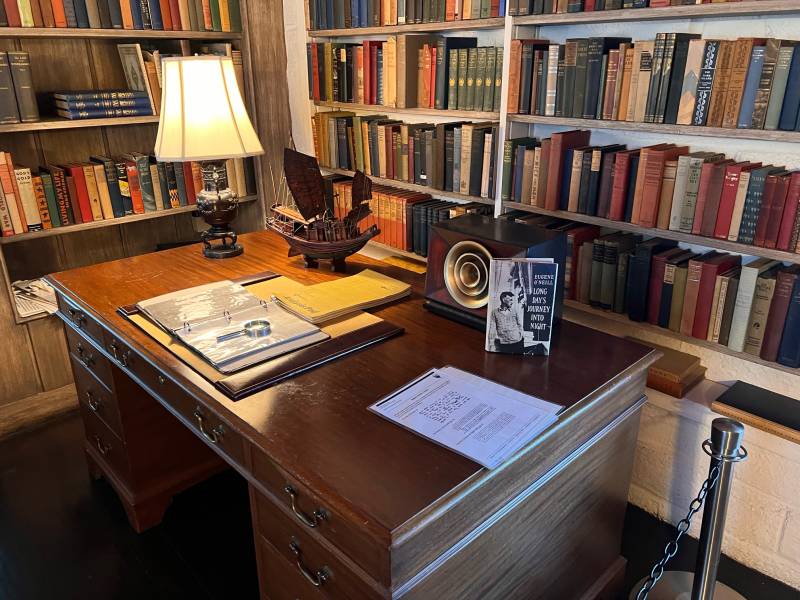

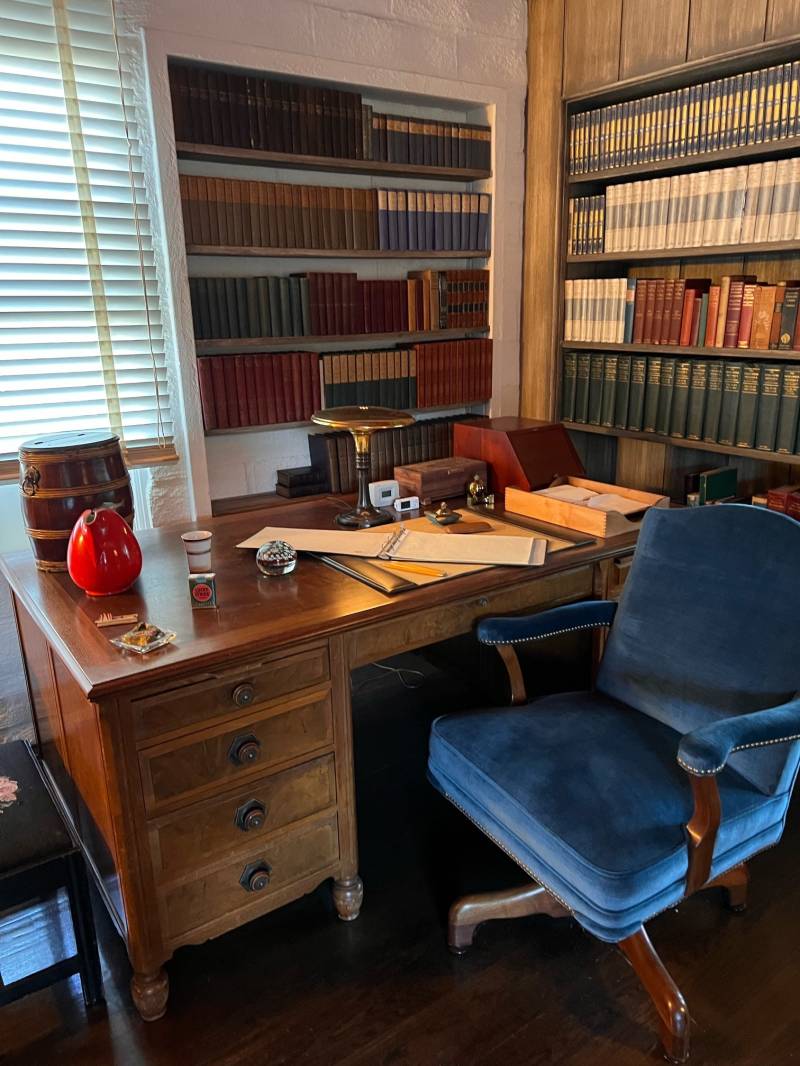

His study was lined with books and had two desks. He would spend 10-12 hours a day in it and would alternate between the desks depending on which play he was writing. He did not type and wrote in long hand. But as the years progressed, a tremor developed in his right arm. His writing grew smaller and smaller, becoming almost illegible by the time he wrote his last play. Carlotta had to use a magnifying glass to type up the text. He tried tape recording his plays but that simply shut off the inspiration to write.

In “Long Day’s Journey into Night,” the action occurs on a single day in August 1912, but there was no such single day. The play captures the tensions that permeated his early life. The play is autobiographical in character and is laced with tragedy. O’Neill was the youngest of three brothers, the second of whom had died during childbirth. He kept thinking he was a poor substitute for that brother. His mother had to be administered morphine when O’Neill was born. She would develop a life-long addiction to that drug, something which Eugene discovered many years later and which haunted him with guilt for the rest of his life.

Eugene did not want this play to be published until 25 years after his death and did not want it to be ever enacted on stage. However, on his death, Carlotta, who was the executor of his will, decided to have it published and performed. It went on to become the most famous of his works.

In the irony of ironies, he was born in a hotel room in 1888 in New York and died in a hotel room in Boston in 1953. When asked to name O’Neill’s best play, a literature student said that his life was the best play. Reflecting on his life, the New York Times wrote that the tallest skyscraper in New York is Eugene O’Neill. In my view, if anyone deserves to be called America’s Shakespeare, it is O’Neill.