125 years ago in August 1897, the might of the British empire was challenged by the Pakhtun tribes around the Peshawar valley. This was the biggest uprising in South Asia against the British since 1857. The cause of this tribal assault against the imperial forces was the promulgation of the 1893 Durand Line as a border, and Britain’s attempts in the years immediately following 1893 to impose its authority in tribal lands by building and occupying forts amongst the tribes.

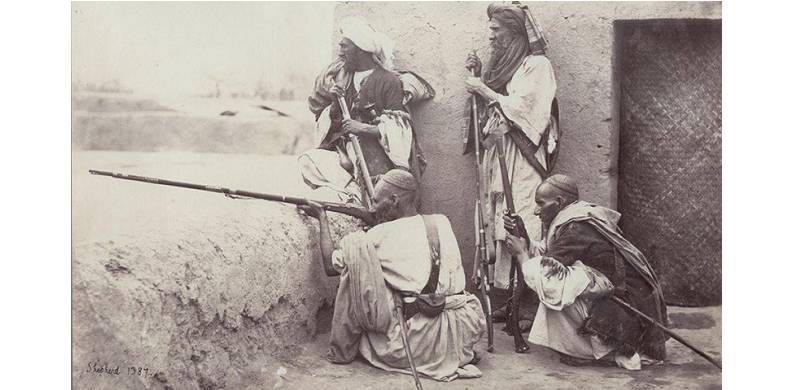

On 23 August 1897, the Afridis rose up to liberate the Khyber Pass and Captain L.J. Shadwell, who served in the battle against the Afridis, wrote a memorable account published in 1898 entitled Lockhart’s Advance through Tirah. In 1898, Shadwell had this to say:

“The loss of the Khyber Pass must undoubtedly have affected the prestige of the British Government and Afghanistan[…] but the capture of Landi Kotal (fort), with its fifty thousand rounds of ammunition, was a great prize.”

The Orakzai tribe, after seeing the splendid victory of the Afridis against the British, also rose up with the Afridis to target the forts on the Samana range, including Fort Saragarhi. Sara means red in Pashto and Garhi means a mud fort, typical of the Pakhtun homes with a tower. Fort Saragarhi was a signalling post between two other forts on the Samana range – which were Fort Lockhart and Fort Gulistan. Lockhart and Gulistan are hidden from one another by an intervening hill.

The 11th of September passed without incident, but the Sikhs would not witness Monday the 13th of September 1897. On Sunday 12 September 1897, the 21 Sikhs of Saragarhi would meet their Lord, along with their Muslim cook. Shadwell writes “On the 12th of September an overwhelming number of tribesmen surrounded the little fort of Saragarhi[…] For nearly seven hours this little band of heroes held out.” However, Shadwell points to the reason the fort fell, which was that it was not constructed as strongly from a defensive position as it should have been. The attackers were able to exploit a blind spot to make an opening into the fort wall: “[…]the fort in which they were, not calculated to stand such a determined attack as was made upon it, for at the corner of the flanking tower was a dead angle[…] a portion of the wall could not have fire brought to bear on it from any portion of the parapet or from loopholes. One or two of the enemy having crept up to this dead angle managed to loosen a corner stone.”

The end game was now beginning: “This sealed the fate of the twenty-one Sikhs, for one stone after stone fell; and the enemy finally crowded into the fort. But all was not over, even yet; for those of the garrison who were still capable of fighting defended an inner enclosure, till the enemy climbed on all sides.”

Shadwell claims: “One wounded Sikh lying on a bed shot four of the enemy before he was himself killed, and the last remaining man having shut himself in the guard room accounted for nearly twenty Pathans till they in desperation set fire to the house.” However, since there were no survivors at Saragarhi, it is implausible for Shadwell to suggest what actually happened in the fort. Shadwell claims he learned about the high casualties allegedly inflicted upon the Pakhtun tribesmen from some of the victorious Pakhtun men who wiped out the occupying Sikh force. It is quite possible that Shadwell was told what he wanted to hear in the hope of eliciting some benefit for the story-teller in return. Nor can Shadwell actually know whether those that told him the accounts of the ‘heroic’ resistance of the Sikhs at Saragarhi actually participated in the battle. The incredible notion that the last surviving Sikh accounted for 20 Pakhtun casualties appears to suggest that the Sikh avenged his 20 fallen comrades before dying. Such attempts at mythologising supposedly brave deeds that never happened deserve utter derision because these claims are mere propaganda.

We need to be clear there is no place for any memorial monuments in Pakistan to the mercenaries that served the colonial forces. To do otherwise is an undignified insult to the many brave Afridi and Orakzai men and women who sacrificed themselves in the freedom struggle

While their Sikh comrades were purportedly bravely holding out at Saragarhi for seven hours, no Sikh or Briton ventured forth from Fort Gulistan or Fort Lockhart to help their brothers in arms to push back the Pakhtun forces from Saragarhi. Shadwell claims that the Pakhtun tribal forces were so strong that it was not possible to do so: “Both of them attempted to send aid from the very slender garrisons they had at their disposal; but the detachments had to be at once recalled, as the enemy were seen in overwhelming numbers, to be trying to outflank them and cut off their line of retreat.” (p.41 Shadwell (1898)).

Shadwell writes of the inaction of Major Des Voeux British commanding officer at Fort Gulistan, describing his inaction to defend his comrades in arms at Saragarhi as being through compulsion, “Major Des Voeux, had to look on at the capture of Fort Saragarhi without being able to afford any assistance.” The good major had 165 men with him, yet Shadwell claims these men would gallantly sally out and engage the surrounding Pakhtuns, even capturing three Pakhtun tribal standards, Shadwell writes “A gallant sortie was made by a Sikh sergeant with sixteen men to capture a standard which the enemy had brought up close to the wall but they were found in great strength, and several of the Sikhs were wounded. Another native sergeant sallying out with more men to the assistance of the first party, the whole force, about twenty-five in number, charged with the bayonet, captured no less than three standards and brought back all their wounded into the fort[…]its complete success greatly raised the morale of the garrison, and at the same time lowered that of the section of the tribesmen to whom the standards belonged.”

The real reason remains unexplained, therefore, as to why the Sikhs at Saragarhi were abandoned. Those at Fort Gulistan could not have been smelling of roses at this time. The smell of their Saragarhi comrades’ roasting flesh under the burning embers of the Fort at Saragarhi in all probability hung heavy in the air. Saragarhi had fallen because Major Des Voeux was more interested in preserving the defence of Gulistan, where according to Shadwell, the foolish Major had his wife with him and their two children. There was also a nurse named Miss Mcgrath. Had these ladies fallen into Pakhtun hands with the fall of Fort Gulistan then the embarrassment that Ajab Afridi inflicted upon the British in 1923 by abducting a British Captain’s daughter and taking her with him into Afridi tribal territory, would have had an earlier precedence amongst his tribal forebears. It appears therefore that Saragarhi was sacrificed by Major Des Voeux, because he feared for the wellbeing of his own family or through general British cowardice by the commanding officers of both Forts. The British had lost women in 1842 to be captured by Sirdar Mohammed Akbar Khan during the first Anglo-Afghan war, had again lost British women to Indians in 1857 and to do so in 1897 would have smacked off carelessness or rather lack of a warrior spirit or manliness.

The real reason remains unexplained, therefore, as to why the Sikhs at Saragarhi were abandoned. Those at Fort Gulistan could not have been smelling of roses at this time. The smell of their Saragarhi comrades’ roasting flesh under the burning embers of the Fort at Saragarhi in all probability hung heavy in the air. Saragarhi had fallen because Major Des Voeux was more interested in preserving the defence of Gulistan, where according to Shadwell, the foolish Major had his wife with him and their two children. There was also a nurse named Miss Mcgrath. Had these ladies fallen into Pakhtun hands with the fall of Fort Gulistan then the embarrassment that Ajab Afridi inflicted upon the British in 1923 by abducting a British Captain’s daughter and taking her with him into Afridi tribal territory, would have had an earlier precedence amongst his tribal forebears. It appears therefore that Saragarhi was sacrificed by Major Des Voeux, because he feared for the wellbeing of his own family or through general British cowardice by the commanding officers of both Forts. The British had lost women in 1842 to be captured by Sirdar Mohammed Akbar Khan during the first Anglo-Afghan war, had again lost British women to Indians in 1857 and to do so in 1897 would have smacked off carelessness or rather lack of a warrior spirit or manliness.The Pakhtun fighters’ numbers at Saragarhi have been grossly inflated for purposes of creating religious tensions by the Bollywood movie industry through the film Kesari released in 2019, which laid claim to a totally ridiculous figure of 10,000 Pakhtun men battling against 21 Sikhs who bravely made a last stand

Shadwell claims the attacking Pakhtun forces on the Samana range were between 10,000 to 15,000 in number. These are inflated figures designed to portray the overall weaknesses of the comparative numerical numbers of the British Indian forces. The exaggerated numbers also serve to protect those such as Major Des Voeux from criticism for failing to rise to the challenge of riding out to save the men at Saragarhi. What appears to be a humiliating defeat is described as being inevitable due to the force of numbers that the British Indian troops allegedly faced. It is unlikely that the terrain around Saragarhi would have supported such vast thousands as Shadwell imagined were assailing Saragarhi. Indeed, Lt Gen HS Panag wrote that “Saragarhi had a cliff facing towards the south and a narrow spur linking it to the ridge. It was not practical for more than 80-100 men to attack at one time, but adequate reserves were available for repeated attacks. Rest of the Pashtuns were cutting/blocking the route to Lockhart and Gulistan and also investing Gulistan and other forts.”

Panag believes the total Pakhtun force that assaulted Saragarhi numbered not more than 1,000 to 1,500.

Shadwell wrote his account one year after the conflict and does not give any definitive number for Pakhtun casualties. Had thousands of Pakhtun martyrs fallen in the capture of Saragarhi, then it follows that Shadwell would surely have mentioned this. Indeed, we can point to Shadwell mentioning two incidents of alleged Sikh bravery at Saragarhi resulting in 24 Pakhtun dead. Had there been a higher number of Pakhtun casualties, then Shadwell would have detailed these.

In 1941, Blackwood magazine published a small book entitled Tales from the Outposts-small wars of the Empire which states that the “enemy admitted a loss of two hundred in the capture of the fort.” The figure of 200 fallen Pakhtuns detailed must be treated with suspicion, given that it appears to be a very exact rounded up figure. The likely number of Pakthun martyrs may well have been much less than the 200 claimed. Potentially we could divide the figure of two hundred by two to come to a more realistic estimate of up to 100 fallen for liberating Saragarhi. Shadwell reveals the truth in his book.

The Pakhtun fighters’ numbers at Saragarhi have been grossly inflated for purposes of creating religious tensions by the Bollywood movie industry through the film Kesari released in 2019, which laid claim to a totally ridiculous figure of 10,000 Pakhtun men battling against 21 Sikhs who bravely made a last stand. While Kipling talked of colonialism in India and the ‘white man’s burden’ to civilise the natives, the truth was a little different. The Sikhs dubbed a ‘martial race’ by the British bore the uncomfortable brown man’s burden of dying to protect white masters, that is of dying for a white man’s empire that exploited them like slaves. This is what happened at Saragarhi.

The only heroics played out at Saragarhi was on the part of the local Pakhtuns, the Afridis and Orakzais who rose with their long-barrelled rifles to the challenge of occupation by giving a bloody nose to the British Indian army that dared invade their territory. Indeed, this is how Shadwell describes the Afridis: “masters of guerrilla warfare, amply provided with arms and ammunition, fleet of foot as goats and inhabiting a country as difficult as any in the world.”

Further the Pakhtun man consumed far less than the Briton or their Indian mercenaries, “A frontier tribesman can live for days on the grain he carries with him, and […]on a few dates.” Man for man the Pakhtun was more than a match for the Briton or their Indian hireling. That was also true for Major-General Yeatman Biggs, the commanding officer of British Indian forces at Fort Lockhart, who spent most of the time when the battle was on going busy with bowel movements as opposed to troop movements.

“The great fatigues and hardships he had gone through at the end of August and in the month of September, when he was engaged in constant movements up and down the Samana range in connection with the attacks made on Forts Gulistan, Saragarhi and other outlying posts had brought on a severe attack of dysentery[…]he was incapable of any severe exertion.”

The Afridis would not needlessly incur casualties on an all-out assault without making a breach through the exterior wall of the fort. This is what Shadwell has to say on Pakhtun casualties which were low in number: “No wonder is it if our losses have been severe in comparison with what we inflicted on them in return.”

The ‘victory’ that the British achieved over the Pakhtun tribes was one in which the British waged a scorched earth campaign against the Pakhtun communities. The aim was to deprive the Pakhtun families of the means to survive through the destruction of animals, crops and food stuffs, as Shadwell reveals:

The ‘victory’ that the British achieved over the Pakhtun tribes was one in which the British waged a scorched earth campaign against the Pakhtun communities. The aim was to deprive the Pakhtun families of the means to survive through the destruction of animals, crops and food stuffs, as Shadwell reveals:“Though of course, we have killed far fewer of them than would have been the case had they opposed us in stand-up fights, still the damage we have done them in consumption of fodder and grain, and in the destruction of their fortified houses and towns has been incalculable. These factors will doubtless be taken into account when the voices of the greybeards make themselves heard above those of the young hot-bloods, and they consider the question of giving in…or indefinitely continuing the war.”

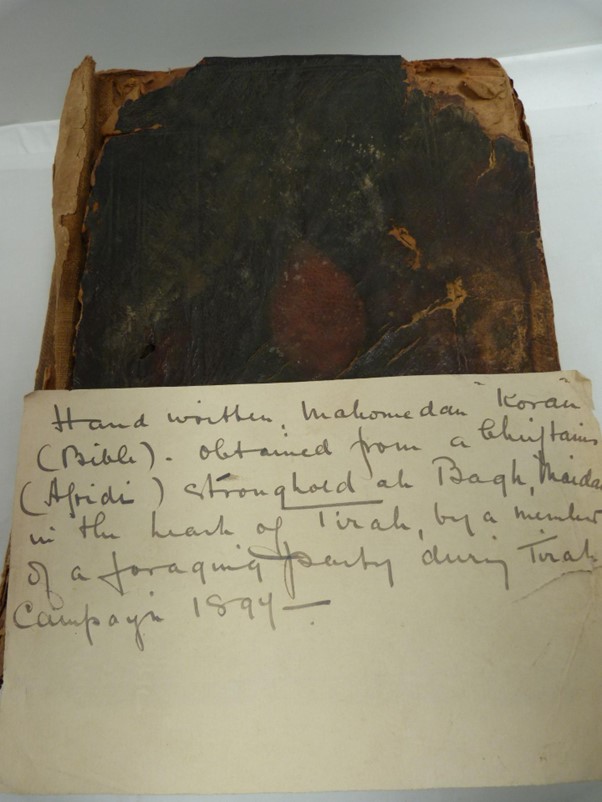

The destruction of Pakhtun homesteads and food stocks was accompanied by looting on the part of the British Indian forces. In particular, the British and Indian troops targeted the Quran for theft. Such stolen Quran appear in British auction houses for sale and the example below was put up for sale in 2020, described as being stolen from an Afridi Chieftain’s home in Bagh Maidan, Tirah.

The British Sikh community is busy celebrating the success of their heroes such as Ranjit Singh and of the supposedly brave deeds at Saragarhi. In 2019 a Saragarhi memorial was unveiled at Wolverhampton, England, depicting a Sikh soldier pulling his sword from his sheath. To glorify imperialism and wars in Wolverhampton through the creation of a colonial-era Sikh soldier statue in an era when statues of those who enslaved black Africans or colonialists like Winston Churchill are being attacked in Britain is perverse. Those who glorify oppressors through such statues in the modern era are handmaidens of imperialism.

The British Sikh community is busy celebrating the success of their heroes such as Ranjit Singh and of the supposedly brave deeds at Saragarhi. In 2019 a Saragarhi memorial was unveiled at Wolverhampton, England, depicting a Sikh soldier pulling his sword from his sheath. To glorify imperialism and wars in Wolverhampton through the creation of a colonial-era Sikh soldier statue in an era when statues of those who enslaved black Africans or colonialists like Winston Churchill are being attacked in Britain is perverse. Those who glorify oppressors through such statues in the modern era are handmaidens of imperialism.Unlike the handmaidens of imperialism serving the British at Saragarhi, the Pakhtun women defended their land alongside their men. “Men and women could be seen by telescope from the Samana Range busily engaged in preparing the pass for defence by erecting sangars, or stone entrenchments, whilst the numerous watch-fires which were visible at night, both in the Khanki valley and on the heights showed that the tribesmen were concentrating their forces.”

Today a painting of Ranjit Singh is on display at the Peshawar Fort. A beautiful Mughal-era fort and Palace complex occupied the grounds on which the present Peshawar Fort stands. The Mughal fort complex was destroyed by the forces of Ranjit Singh. To hang a portrait of this man who destroyed the beautiful Peshawar Mughal Fort, destroyed the Jehanara Begum Jamia Mosque that had stood in Gor Khattri, banned the Azan and forbade the Pakhtun delicacy of a beef chappali kebab is an insult to the people of Peshawar. A Sikh memorial monument has been proposed for Saragarhi.

We need to be clear there is no place for any memorial monuments in Pakistan to the mercenaries that served the colonial forces. To do otherwise is an undignified insult to the many brave Afridi and Orakzai men and women who sacrificed themselves in the freedom struggle.

The British have celebrated their military disasters in movies such as Dunkirk (2017), the Indians followed in the path of the white sahib with their movie Kesari (2019). Let us remember the brave Pakhtun martyrs who wiped the stain of enemy occupation from the homeland.

There are some in the Pakistani state who seek to glorify the people that occupied their lands for imperialism, in the hope of earning money from Sikh tourists. These people need to hold their heads in shame. It is instead time to honour our heroes of yesteryear and our contemporary heroes. If we do not respect the deeds of our brave fellows of yesteryear, we are a people with no respect for ourselves or for valuing the battle against imperialism.