The deletion of Concurrent List and various entries contained in the Federal Legislative List by the 18th Amendment provided new avenues to the provinces for raising revenues to spend more money for social services. It is, however, extremely painful that even after 13 years having elapsed, the provinces have not realised the importance of these changes because all of them have failed to expand their tax base using the new taxation powers.

There is no political will on the part of provinces to levy and collect taxes from the rich and mighty by imposing progressive taxes like estate duties, wealth taxes and taxes on the gain of immovable property. The power to levy duties in respect of succession to property and estate duties in respect of property under items 45 and 46 respectively of the Federal Legislative List, before omission by the 18th Amendment, was with the Federation. Now it exclusively lies with the provinces by virtue of Article 142(c) of the Constitution.

While the provinces are not levying or collecting progressive taxes, including agricultural income tax from rich absentee landowners, the federal government is unlawfully collecting income tax on gain of immovable property, based on a misreading of the amended position of item 50, Part I of the Federal Legislative List (FLL), Fourth Schedule to the Constitution [hereinafter “Entry 50”].

The National Assembly, through the Finance Act 2012 amended section 37(5) of the Income Tax Ordinance, 2001 and for the first time levied capital gains tax (CGT) on the disposal of immovable property. Punjab Assembly reintroduced CGT in Finance Act 2013, which had been abolished in 1979, contesting the Parliament’s legislative competence.

Who has the right under the Constitution to levy this tax? Entry 50 of FLL, Fourth Schedule to the Constitution [hereinafter “Entry 50”] gives exclusive power to the provincial assemblies to levy “taxes on immovable property”. Under Entry 50, the Parliament can only levy taxes on capital value of assets excluding taxes on immovable property. After the 18th Amendment, provinces failed to contest unlawful act of the federal government of collecting tax on gain of immoveable property.

There has been no serious debate until today on whether the imposition of CGT on immovable property by the National Assembly in 2012 was in line with the Constitution or not. Was it based on a correct interpretation of the amended language of Entry 50, Part I of FLL, Fourth Schedule to the Constitution, especially when the Punjab Assembly also used the same in 2013?

The right to tax gains on immovable property situated within their territories is exclusively with the provinces. Strangely, no province, except Punjab, till today has taken cognizance of the fact that the right to impose CGT, Capital Value Tax (CVT) or wealth tax etc on immovable property indisputably vests with provinces after the 18th Amendment. The Punjab Assembly correctly read Entry 50 and levied CVT on immovable property vide Finance Act 2012 and CGT through section 9 of Finance Act 2013 that reads as under:

“Capital gains tax on immovable property– (1) This section shall have effect notwithstanding anything contained in any other law.

(2) For purposes of this section–

(a) “acquisition” means transfer of property through any mode including gift, bequest, will, succession, inheritance, devolution, dissolution of an association of persons or, winding up or liquidation of a company;

(b) “Board of Revenue” means the Board of Revenue established under the Punjab Board of Revenue Act, 1957 (XI of 1957);

(c) “Collector” means the Collector of the district appointed under the Punjab Land Revenue Act, 1967 (XVII of 1967) and includes the Collector of a subdivision or any other officer specially empowered by the Board of Revenue to exercise and perform the functions of the Collector;

(d) “Government” means Government of the Punjab;

(e) “person” includes–

(i) an individual;

(ii) an association of persons;

(iii) a company;

(iv) a body corporate;

(v) a foreign government;

(vi) a political subdivision of a foreign government; and

(vii) a public international organization;

(f) “recorded value” means the value declared by the transferor in the instrument, provided that the declared value of the property shall not be less than the value specified in the valuation table notified by the Collector of the district; and

(g) “tax” means capital gains tax on sale of an immovable property and includes any penalty, fee and charge or any sum or amount leviable or payable under this section.

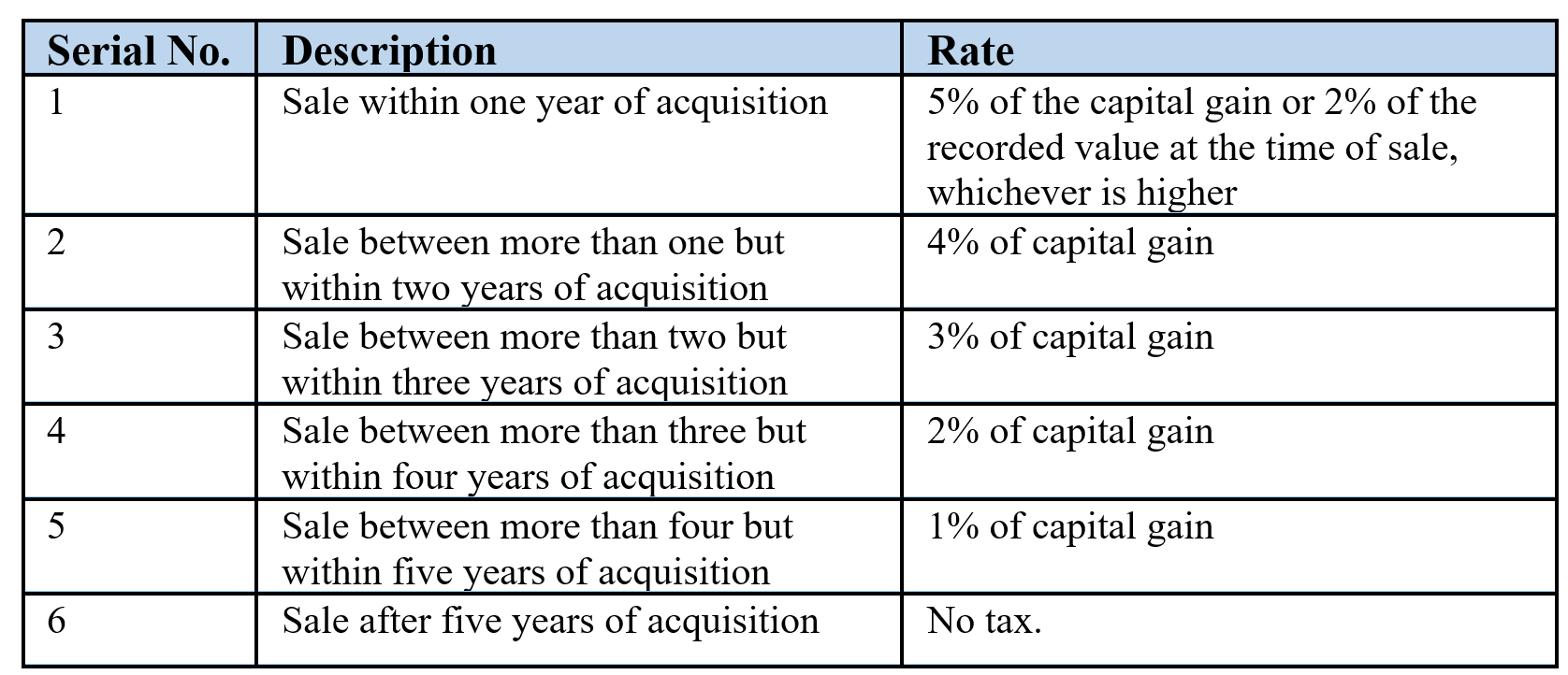

(3) A gain occurring from the sale of immovable property by a person in a tax year shall be chargeable to tax in that year at the following rate:

(4) The Collector shall determine the capital gain through calculating difference in valuation at the time of acquisition and sale on the basis of valuation table notified by the Collector of the district under section 27-A of the Stamp Act, 1899 (II of 1899) or the recorded value in the transfer deed, whichever is higher.

(5) The Collector shall assess and collect the tax, and for this purpose, may exercise any power of the Collector under section 6 of the Punjab Finance Act 2010 (VI of 2010).

(6) For purposes of appeal, review or revision, an order passed under this section shall be deemed to be an order of a Revenue Officer within the meanings of sections 161, 162, 163 and 164 of the Punjab Land Revenue Act 1967 (XVII of 1967).

(7) Where the tax has been recovered from a person not liable to pay the same or in excess of the amount actually payable, an application may, in writing, be made to the Collector for the refund of the tax or the excess amount within one year of the payment of the tax.

(8) The Board of Revenue may, by notification in the official Gazette, make provisions relating to the collection and recovery of the tax or for ancillary matters.

(9) The Government may, by notification in the official Gazette, exempt a class of immovable property or a class of persons from the levy or recovery of the tax subject to such conditions as may be specified in the notification”.

In 2010, the Revenue Advisory Council (RAC) of the Federal Board of Revenue (FBR) recommended the imposition of CGT on disposal of immoveable property. Purportedly, FBR obtained a “favorable” opinion from the Law & Justice Division of Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs that after the 18th Amendment, the Federal Government was entitled to levy CGT on immoveable property.

In the light of recommendation of Law & Justice Division of Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs, RAC asked the FBR to propose to the government methodology for the imposition of CGT on immovable property. In the past, a group working on tax reforms proposed to the government 10% CGT on the sale of immoveable property after excluding impact of inflation, depreciation of rupee and actual price paid on the purchase from the present market price.

The FBR was of the view that the real issue in the imposition of CGT was not constitutional bar after 18th Amendment, but the correct valuation of immoveable properties as sellers and buyers conceal actual payment—in majority of the cases, sale deeds were three times lower than the fair market value of actual transaction.

Prior to the amendment in Entry 50 through 18th Amendment, the National Assembly had no power to levy capital gain tax on disposal of immovable property.

Entry 50 of Part I of the Federal Legislative List, as amended by the 18th Amendment, reads as under:

“50. Taxes on the capital value of the assets, not including taxes on immovable property”.

Prior to the amendment, the language of Entry 50 of the Federal Legislative List read, “50. Taxes on the capital value of the assets, not including taxes on capital gains on immovable property”.

Historically, gains on the disposal of immovable property fell outside the ambit of income taxation. Section 37(5)(c) of the Ordinance before amendment provided that “capital asset does not include any immovable property”. However, after misinterpretation of amended Entry 50 by Law & Justice Division, the Finance Act 2012 removed these words to bring gain on disposal of immovable property, including agricultural lands, within the ambit of income tax. Through Finance Act 2012 a new section 236C was also inserted in the Income Tax Ordinance, 2001 for collection of tax from the seller at the time of transfer of property. It was explained by FBR in Circular No. 2 of 2012 as under:

"To overcome the administrative problems in respect of collection of CGT on disposal of immoveable property and to keep a track of the transactions of immoveable property adjustable advance withholding tax @ 0.5% of the consideration received on sale/transfer of immoveable property was levied on sellers/transferors of immoveable property under section 236C of the Income Tax Ordinance, 2001.

It is clarified that the advance tax to be collected under section 236C has been introduced for the purposes of providing a mechanism for collection of capital gain tax on disposal of immoveable property. The actual quantum of capital gain and tax payable thereon is to be computed at the time of filing of return of income. Section 236C is not an independent provision and does not operate in isolation. Since Capital Gain Tax has been imposed only on disposal of properties held for a period up to two years therefore, advance tax is also to be collected from sellers who held the immoveable properties for a period up to two years.”

In 2012, at the time of imposition of capital gain tax on disposal of immovable property FBR said: “It would help in broadening of tax base and substantially enhance revenue. It would play a major role in plugging one of the loopholes for whitening untaxed money in the name of capital gains. The imposition of the CGT on immovable property is in line with the principle that every income is taxable unless specifically exempted. It would also bring stability in the prices of immovable property conveying healthy message to the masses”.

None of the above goals set by FBR has been achieved since imposition of CGT. Collection by FBR, as per official documents, is still miserably low and the prices of immovable property since then have skyrocketed beyond anybody’s imagination.

Later, section 236K was also inserted in the Ordinance in 2014 for collection of advance tax from buyers at the time of purchase/transfer of immovable property. The Finance Act, 2019 afterwards enhanced rates of advance tax on sale and purchase of immovable property as well as on capital gains arising out of its disposal.

Entry 50 clearly debars the federation from levying any kind of tax on immovable property. The Law Ministry and FBR did not realise that even CVT on immoveable property was transferred to provinces in the wake of 18th Amendment. If federal government cannot levy any tax on immovable property, how can it impose “capital gain” arising out of immovable property? This simple proposition was ignored by both Law Ministry/FBR and even Sindh and Lahore High Court in some recent judgements.

It is worthwhile to mention that the erstwhile Wealth Tax Act, 1963, levied under Entry 50 was challenged under Article 199 of the Constitution. The matter went up to the Supreme Court of Pakistan. In its decision reported as Haji Mohammad Shafi and Others v Wealth tax Officers and Others 1992 PTD 726, the Supreme Court held that Parliament under Entry 50 of Federal Legislative List was competent to levy wealth tax on the value of assets. It was held that the manner in which valuation of any immovable asset was made could not be termed as “tax on capital gain”. Before the amendment in Entry 50 by the 18th Amendment, the federation was barred from taxing “capital gain on immovable asset.” Now this bar has been extended to “taxes on immovable property”.

One wonders how by just omission of words “capital gains” in Entry 50 of the Federal Legislative List, FBR and Law & Justice Division concluded that right to taxation was shifted to the federal government. They failed to see that second part of Entry 50 is couched in a negative phrase.

The phrase “not including taxes on immovable property” in Entry 50 cannot be read to “include taxes on capital gains on immovable property.” A plain reading of Entry 50 of Federal Legislative List, as it stands now, confirms that the National Parliament can levy taxes on capital value of moveable assets but has no authority to levy taxes, including capital gain tax, on immovable property. It is obvious that taxes include tax on capital gains.

The Punjab Assembly correctly read Entry 50 and levied tax on gain of immovable property in 2013. If the federal government is of the view that its interpretation of Entry 50 of Federal Legislative List is correct it should refer the matter to the Supreme Court under Article 184(1) of the Constitution that has exclusive jurisdiction in any dispute between any two or more Governments.

It is an established law that entries contained in the Fourth Schedule to the Constitution are mutually exclusive and for one taxable event two entries cannot be invoked—Pakistan International Freight Forwarding Association v Province of Sindh & Another 2017 PTD 1 followed in Pakistan Mobile Communication Ltd & 2 Others v Federation of Pakistan & Others (2022) 125 TAX 401 (H.C. Kar.). This has not been discussed in the latest order [Muhammad Osman Gull v Federation of Pakistan etc in Writ Petition No. 52559 of 2022] of Lahore High Court issued on April 6, 2023 holding that National Assembly can levy CVT on immoveable property even after the 18th Amendment. It appears that proper assistance to the Court was not rendered. Hopefully, the above points will be agitated when the order is challenged through intra-court appeal.