If one were to go by what one reads in print media or watches on TV, they could be forgiven for having no idea about the ghastly death of Arman Luni - allegedly at the hands of police. But then, going by mainstream media in general, one could easily be forgiven for not having any idea about what Pakhtun Tahaffuz Movement (PTM) is and why its demands, discourse and provenance are such a source of anxiety for official quarters in Pakistan.

Mainstream media has - for the most part - dutifully stuck to a policy of ignoring the PTM, what it does and what is done to it. Whether or not powerful quarters in Pakistan actually “recommended” that the media take this approach, the fact remains that the policy of silence speaks volumes for what Pakistan’s media moguls and editors imagine official policy to be.

An anecdote will suffice to show how some influential quarters in Pakistani officialdom view such issues - unofficially, of course.

Two people from Pakistan – a writer and an official – sat down over coffee in Europe. They were not friends, but the meeting was necessary between these two important people; each needed to understand what the other side was thinking on a range of topics. Freedom of expression was also discussed.

“The news of censorship and controls over the media is very worrying sir,” the writer said. “Why must it be that way?”

The military man smiled, as if there was a simple answer to this question that the writer could not comprehend. “Let us put it this way: imagine one has a daughter who does not behave in ways society considers respectable or honourable. She parties all night and hangs around with boys. Now, I do not have a problem with such a thing; one can do as they please, as long as it is done privately and quietly. Now, imagine this girl has a younger brother – who means well and speaks the truth. I do not have a problem with the truth; but I cannot allow my son to go around telling the world that my daughter is dishonouring the family.”

He waited for the weight of his words to sink in.

The son is, of course, the electronic and print media in Pakistan. The daughter is everything else. The son seems to have been silenced or at least made more pliant, but this family – intent on burying all its secrets in the backyard – underestimated the cry of a newborn in the neighborhood: social media.

It was social media that highlighted the brutal murders of a family by some Counter Terrorism Department officials in Sahiwal last month. It was when the public watched videos of the two children who lost their parents and their sister in the ‘encounter’ that there was an outcry over the highhandedness of security officials and the government was forced into action.

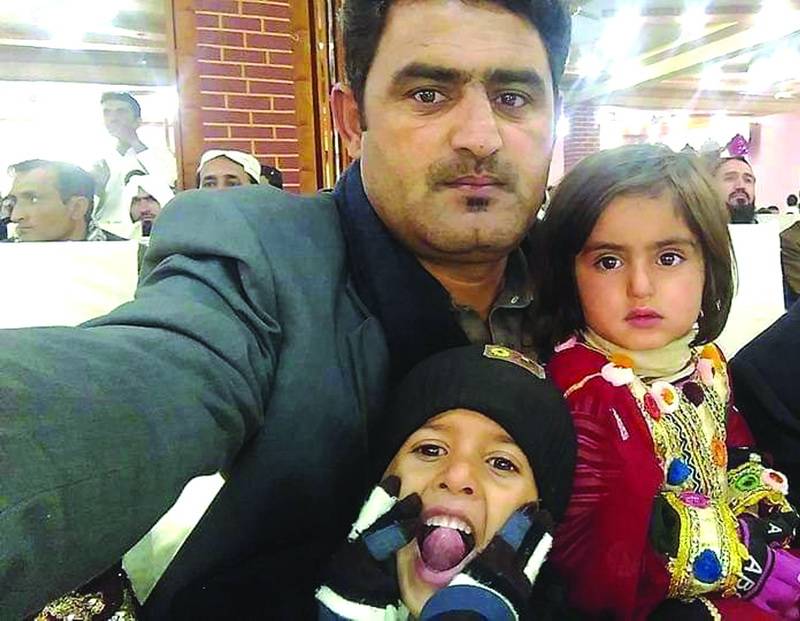

It was also social media that broke the news of the killing of Arman Luni, a core committee member of the PTM in Loralai on February 2. It was a dark moment for the young people organizing with the PTM. Only a few hours earlier, the main trend on their forums was the one-year anniversary of the movement. It was a moment for one to examine the canvas as it appears so far – the successes in this short time and the challenges ahead. But if there was any celebration, it was short-lived: Luni’s death – indeed the first casualty for the PTM – served as a brutal reminder of the state’s continued unease with the burgeoning movement in the former Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) and also became an indicator of some of PTM’s troubles ahead.

Where does this unease and nervousness come from? Some quarters within the PTM that believe over the last one year, the presence and the vibrancy of the movement in certain zones have made it difficult for the state to maintain havens for proxies to influence affairs in Afghanistan. These voices within the PTM believe that the state would like to contain their activities to certain areas and wants to maintain certain other districts as havens for assets to be used in Afghanistan.

The PTM, campaigning for civil liberties, has gained momentum in north and south Waziristan, Dera Ismail Khan, Tank and Bannu. Some commentators believe that it would suit certain quarters to regain control of South Waziristan and prevent the PTM from gaining traction in the Pakhtun districts of Balochistan. This is why Arman Luni’s death in Loralai is significant: he had organized a peaceful sit-in to protest the killing of 9 policemen by the TTP. The death of a central organiser in Balochistan signaled that this was hostile territory.

Other voices in the PTM believe that this issue is beyond unease and nervousness. A few weeks ago, an interview by DG ISPR Asif Ghafoor was aired in which he was quoted saying that the state was like a mother and it should have a maternal relationship with its citizens. “We are with the PTM and their friends as they pursue their legitimate demands.” This statement had raised many eyebrows and many had wondered if this was some kind of signaling to deescalate tensions.

In several other statements, the ISPR, through its spokesman Major General Asif Ghafoor, maintained that the PTM should not go beyond their original three demands:

“They have three demands; missing persons, reduction in check-posts and clearance of mines. Pakistan Army has reduced number of check posts and with the completion of fence on Pak-Afghan border next year, the security situation would further improve,” DG ISPR had told media in December.

“We can’t call back the troops given the cross border threats from Afghanistan. 43 teams are working on mines in different districts and they have cleared 44 percent areas,” he had said.

At the same time, he had also warned the PTM to not cross “red lines” – which he did not clearly define.

There is a feeling incidents such as the killing of Arman Luni at the hands of a policeman, arrests of protesting activists on Tuesday and a security escort opening fire on a car transporting Manzoor Pashteen, Ali Wazir and Mohsin Dawar after Luni’s funeral all point to an intent to provoke some kind a violent reaction. This would then, presumably, justify some sort of larger crackdown.

Non-violent resistance has been an essential character of this movement, and some commentators believe that such incidents are meant to elicit an angry response from the young men and women leading this moment. This is why, these voices within the PTM say, it is imperative to remain peaceful. And this is why many PTM activists cheerfully courted arrest when police came to round them up from Islamabad Press Club on Tuesday.

Since the legal and administrative reforms outlined at the time of FATA’s merger into Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa last year have not yet been implemented, it is believed that tensions between the people and the state will persist. Absence of judicial and civilian institutions to take up day-to-day issues of the people will continue to bring the PTM and the security forces to a head.

One hopes, at the end of the day, that all stakeholders involved here understand the importance of a political, non-violent solution to the problem. Also, one dares to hope that the Powers That Be acknowledge the need to give the PTM a fair hearing.

The author can be contacted on

Twitter @aimamk

Mainstream media has - for the most part - dutifully stuck to a policy of ignoring the PTM, what it does and what is done to it. Whether or not powerful quarters in Pakistan actually “recommended” that the media take this approach, the fact remains that the policy of silence speaks volumes for what Pakistan’s media moguls and editors imagine official policy to be.

An anecdote will suffice to show how some influential quarters in Pakistani officialdom view such issues - unofficially, of course.

Two people from Pakistan – a writer and an official – sat down over coffee in Europe. They were not friends, but the meeting was necessary between these two important people; each needed to understand what the other side was thinking on a range of topics. Freedom of expression was also discussed.

Non-violent resistance has been an essential character of this movement, and some commentators believe that such incidents are meant to elicit an angry response from the young men and women leading this moment

“The news of censorship and controls over the media is very worrying sir,” the writer said. “Why must it be that way?”

The military man smiled, as if there was a simple answer to this question that the writer could not comprehend. “Let us put it this way: imagine one has a daughter who does not behave in ways society considers respectable or honourable. She parties all night and hangs around with boys. Now, I do not have a problem with such a thing; one can do as they please, as long as it is done privately and quietly. Now, imagine this girl has a younger brother – who means well and speaks the truth. I do not have a problem with the truth; but I cannot allow my son to go around telling the world that my daughter is dishonouring the family.”

He waited for the weight of his words to sink in.

The son is, of course, the electronic and print media in Pakistan. The daughter is everything else. The son seems to have been silenced or at least made more pliant, but this family – intent on burying all its secrets in the backyard – underestimated the cry of a newborn in the neighborhood: social media.

It was social media that highlighted the brutal murders of a family by some Counter Terrorism Department officials in Sahiwal last month. It was when the public watched videos of the two children who lost their parents and their sister in the ‘encounter’ that there was an outcry over the highhandedness of security officials and the government was forced into action.

It was also social media that broke the news of the killing of Arman Luni, a core committee member of the PTM in Loralai on February 2. It was a dark moment for the young people organizing with the PTM. Only a few hours earlier, the main trend on their forums was the one-year anniversary of the movement. It was a moment for one to examine the canvas as it appears so far – the successes in this short time and the challenges ahead. But if there was any celebration, it was short-lived: Luni’s death – indeed the first casualty for the PTM – served as a brutal reminder of the state’s continued unease with the burgeoning movement in the former Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) and also became an indicator of some of PTM’s troubles ahead.

Where does this unease and nervousness come from? Some quarters within the PTM that believe over the last one year, the presence and the vibrancy of the movement in certain zones have made it difficult for the state to maintain havens for proxies to influence affairs in Afghanistan. These voices within the PTM believe that the state would like to contain their activities to certain areas and wants to maintain certain other districts as havens for assets to be used in Afghanistan.

The PTM, campaigning for civil liberties, has gained momentum in north and south Waziristan, Dera Ismail Khan, Tank and Bannu. Some commentators believe that it would suit certain quarters to regain control of South Waziristan and prevent the PTM from gaining traction in the Pakhtun districts of Balochistan. This is why Arman Luni’s death in Loralai is significant: he had organized a peaceful sit-in to protest the killing of 9 policemen by the TTP. The death of a central organiser in Balochistan signaled that this was hostile territory.

Other voices in the PTM believe that this issue is beyond unease and nervousness. A few weeks ago, an interview by DG ISPR Asif Ghafoor was aired in which he was quoted saying that the state was like a mother and it should have a maternal relationship with its citizens. “We are with the PTM and their friends as they pursue their legitimate demands.” This statement had raised many eyebrows and many had wondered if this was some kind of signaling to deescalate tensions.

In several other statements, the ISPR, through its spokesman Major General Asif Ghafoor, maintained that the PTM should not go beyond their original three demands:

“They have three demands; missing persons, reduction in check-posts and clearance of mines. Pakistan Army has reduced number of check posts and with the completion of fence on Pak-Afghan border next year, the security situation would further improve,” DG ISPR had told media in December.

“We can’t call back the troops given the cross border threats from Afghanistan. 43 teams are working on mines in different districts and they have cleared 44 percent areas,” he had said.

At the same time, he had also warned the PTM to not cross “red lines” – which he did not clearly define.

There is a feeling incidents such as the killing of Arman Luni at the hands of a policeman, arrests of protesting activists on Tuesday and a security escort opening fire on a car transporting Manzoor Pashteen, Ali Wazir and Mohsin Dawar after Luni’s funeral all point to an intent to provoke some kind a violent reaction. This would then, presumably, justify some sort of larger crackdown.

Non-violent resistance has been an essential character of this movement, and some commentators believe that such incidents are meant to elicit an angry response from the young men and women leading this moment. This is why, these voices within the PTM say, it is imperative to remain peaceful. And this is why many PTM activists cheerfully courted arrest when police came to round them up from Islamabad Press Club on Tuesday.

Since the legal and administrative reforms outlined at the time of FATA’s merger into Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa last year have not yet been implemented, it is believed that tensions between the people and the state will persist. Absence of judicial and civilian institutions to take up day-to-day issues of the people will continue to bring the PTM and the security forces to a head.

One hopes, at the end of the day, that all stakeholders involved here understand the importance of a political, non-violent solution to the problem. Also, one dares to hope that the Powers That Be acknowledge the need to give the PTM a fair hearing.

The author can be contacted on

Twitter @aimamk