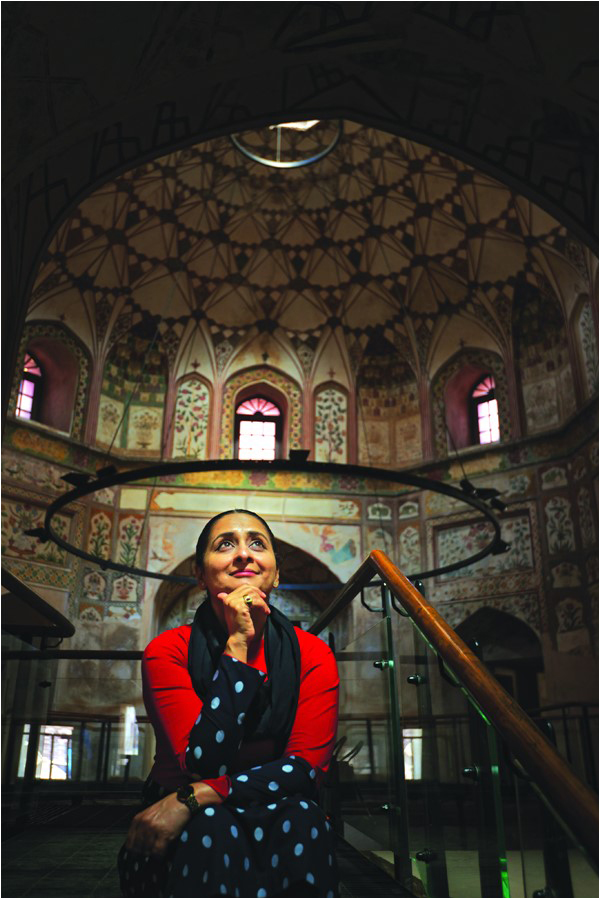

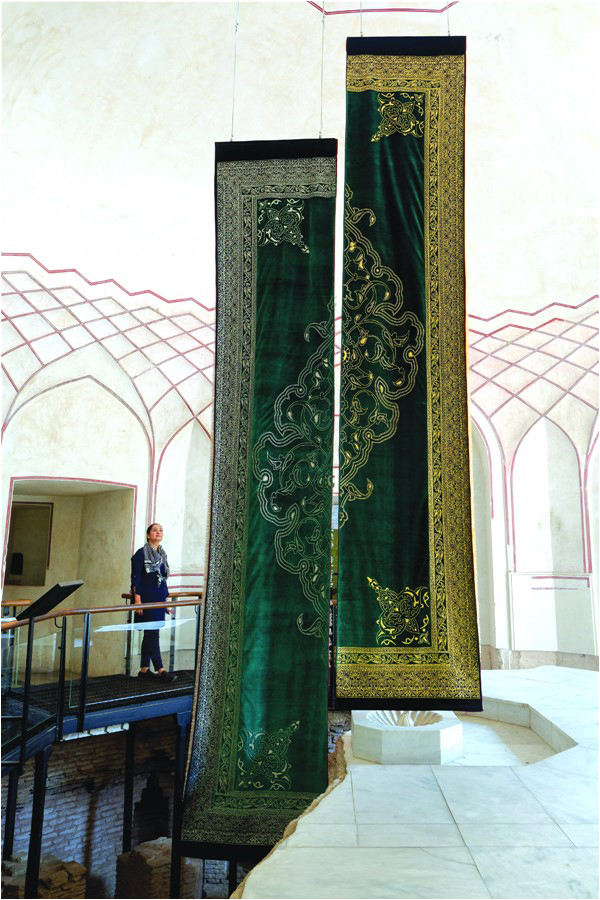

Every one connects with a work of art differently. At times it requires conscious effort but sometimes it happens effortlessly. Aisha Khalid’s “Your way begins on other side” (2014) is a piece of work that captivated me effortlessly. Despite its size (6 feet by 18 feet) and opulence – made with stainless and gold plated pins on velvet and silk – the gigantic drapery immediately puts the viewer in a trance. Khalid is one of the main protagonists of contemporary miniature emerging from Pakistan and has used her skills to do paintings, textiles and installations on a much bigger scale than is usual, and also to indulge in performance work.

Khalid belongs to the generation of artists who were taught traditional miniature by Ustad Bashir Ahmed in the early 1990s at the National College of Arts, Lahore. Not among the favoured students, she was once given a difficult assignment on Persian miniature with minimal instructions. An extremely hardworking, disciplined and no-nonsense person, Khalid ably produced the required result in the assignment. A typical ustad, Ahmed checked her hands to assess if she did the work herself. Once content on that count, Ahmed, as she vividly remembers, declared that he was seeing success in her hands.

As a youngster Khalid liked doing embroidery and even stitched her own clothes. She kept a collection of unstitched cloth pieces and laces to garnish her products in a goody bag. In her first trip abroad she was able to visit Makkah and was captivated by the image of the “Gilaf-e-Kaaba.” Moving backwards on her oeuvre, it is easy to link the dots in her works especially tapestries like “Your way begins on the other side”, which are rooted in the sensibility attained through doing embroidery and her spiritual experience and images of the Holy Kaaba.

Her work features some key elements. These include geometric patterns, flower and amoebic patterns. Figures appeared in her work but then disappeared many years ago. So has the imagery of the veil.

The amoebic design in her work is the hem of the traditional covering garment or burqa. It represents an opening or a vortex depicting the human presence in Khalid’s work.

The flowers in her work are characters. It started with the typical lotus of miniature, became a rose and then turned into a tulip in the Netherlands. Khalid has also used the tulip to portray women in the Western world in her work.

As an artist Khalid has moved from addressing local social and gender issues to a post-9/11 global concern for identity and roots in her work. Just around September 2001, she got the opportunity to study in the Netherlands, where her quest to find her own roots started in that short sojourn abroad. As she travelled more she moved away from the stereotypical issues expected to be addressed by artists from her part of the world to questioning the stereotypes imposed by the West on these artists.

Khalid says that she does not want to be bracketed in a certain category as is done for many artists from the developing world. “I am a Pakistani woman and I represent all women in Pakistan” she insists.

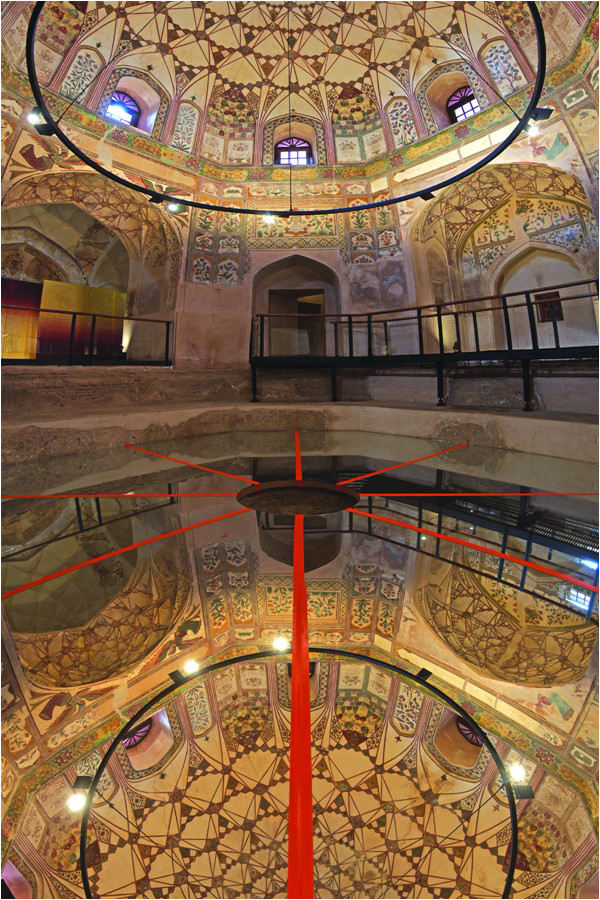

Khalid’s work became more intense with geometric patterns as she moved out of canvas and attempted larger scale site specific commissions in Kabul (2008), Venice (2009) and then in Manchester, titled “Larger than Life” (2012). Here geometry is the language that she chooses to project her imagery conceived in miniature practice and spirituality.

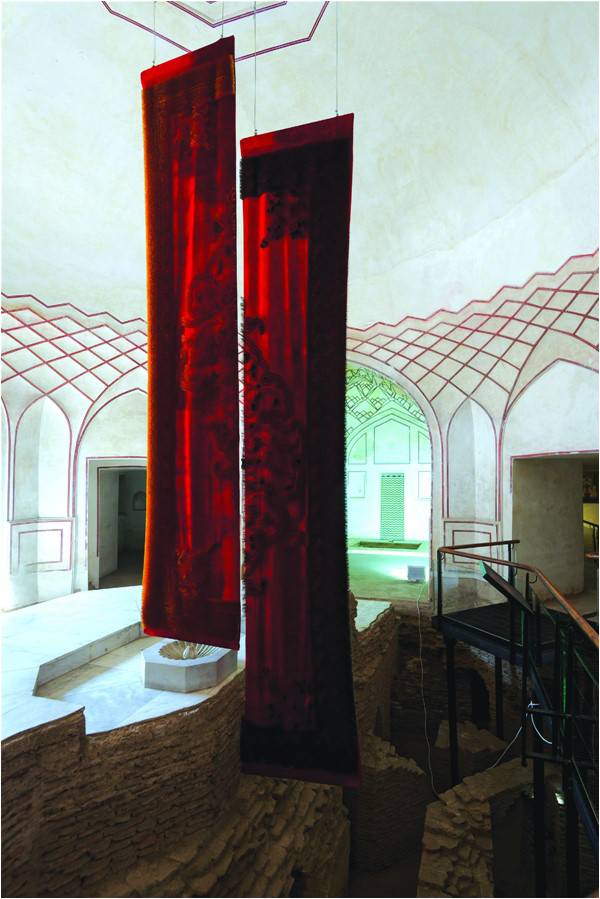

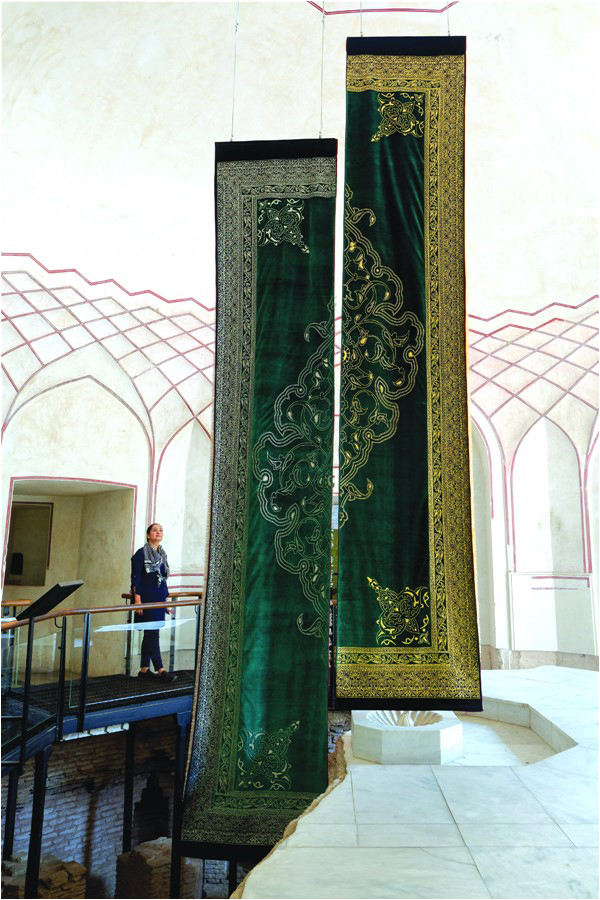

In her work Khalid uses softer tones of miniature but mostly intense shades of colours. As a result we see black and shades of dark green, red and gold used to ornate her work – be it textile, painting or installations.

Though she did embroidery work earlier, her critical foray into textiles started with her 2011 Sharjah Biennale work “Kashmiri Shawl” and “Appear as you are, Be as you appear” – a jacket done in pins and needle. “Time and Patience”, though a bit raw, followed in the 2013 Moscow Biennale.

Her tapestries carry the traditional chahar bagh structure and on closer scrutiny show battling creatures. It communicates the essence of a spiritual journey where dark forces coexist with beauty and ease with suffering – symbolised by a velvety surface and carefully inserted designs and gold-plated pins.

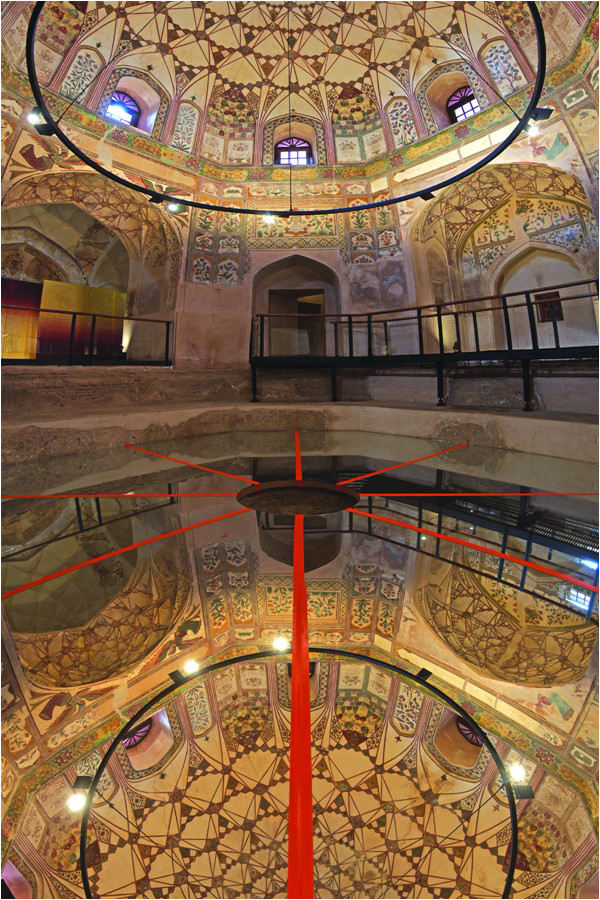

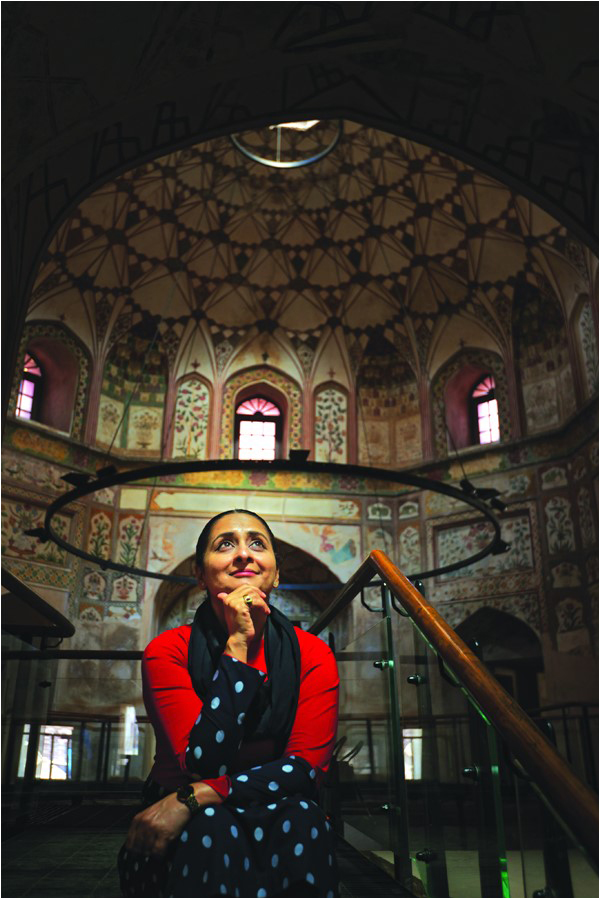

Khalid has used mirrors to paint and create a four-dimensional effect. Her work at the Venice Biennale 2009 “If you are everywhere you are nowhere, if you are somewhere you are everywhere” was a site specific installation at Mohatta Palace Museum Karachi in 2010. Her recent work for the 2018 Lahore Biennale at the Shahi Hamam was titled “More beautiful for having been broken.” Her latest commission at the newly opened Islamabad airport is dazzling.

Last year, Khalid with her husband Imran Qureshi, did the biggest show of her career in Pakistan “Two wings to fly not one.” After seeing the show Ustad Bashir Ahmed acknowledged that his student has taken the traditional art form taught by him to a new level. The Ustad’s prophecy about his student has come to fruition.

The writer can be reached at smt2104@caa.columbia.edu

Khalid belongs to the generation of artists who were taught traditional miniature by Ustad Bashir Ahmed in the early 1990s at the National College of Arts, Lahore. Not among the favoured students, she was once given a difficult assignment on Persian miniature with minimal instructions. An extremely hardworking, disciplined and no-nonsense person, Khalid ably produced the required result in the assignment. A typical ustad, Ahmed checked her hands to assess if she did the work herself. Once content on that count, Ahmed, as she vividly remembers, declared that he was seeing success in her hands.

As a youngster Khalid liked doing embroidery and even stitched her own clothes. She kept a collection of unstitched cloth pieces and laces to garnish her products in a goody bag. In her first trip abroad she was able to visit Makkah and was captivated by the image of the “Gilaf-e-Kaaba.” Moving backwards on her oeuvre, it is easy to link the dots in her works especially tapestries like “Your way begins on the other side”, which are rooted in the sensibility attained through doing embroidery and her spiritual experience and images of the Holy Kaaba.

Her work features some key elements. These include geometric patterns, flower and amoebic patterns. Figures appeared in her work but then disappeared many years ago. So has the imagery of the veil.

The amoebic design in her work is the hem of the traditional covering garment or burqa. It represents an opening or a vortex depicting the human presence in Khalid’s work.

Aisha Khalid has moved from addressing local social and gender issues to a post-9/11 global concern for identity and roots in her work

The flowers in her work are characters. It started with the typical lotus of miniature, became a rose and then turned into a tulip in the Netherlands. Khalid has also used the tulip to portray women in the Western world in her work.

As an artist Khalid has moved from addressing local social and gender issues to a post-9/11 global concern for identity and roots in her work. Just around September 2001, she got the opportunity to study in the Netherlands, where her quest to find her own roots started in that short sojourn abroad. As she travelled more she moved away from the stereotypical issues expected to be addressed by artists from her part of the world to questioning the stereotypes imposed by the West on these artists.

Khalid says that she does not want to be bracketed in a certain category as is done for many artists from the developing world. “I am a Pakistani woman and I represent all women in Pakistan” she insists.

Khalid’s work became more intense with geometric patterns as she moved out of canvas and attempted larger scale site specific commissions in Kabul (2008), Venice (2009) and then in Manchester, titled “Larger than Life” (2012). Here geometry is the language that she chooses to project her imagery conceived in miniature practice and spirituality.

In her work Khalid uses softer tones of miniature but mostly intense shades of colours. As a result we see black and shades of dark green, red and gold used to ornate her work – be it textile, painting or installations.

Though she did embroidery work earlier, her critical foray into textiles started with her 2011 Sharjah Biennale work “Kashmiri Shawl” and “Appear as you are, Be as you appear” – a jacket done in pins and needle. “Time and Patience”, though a bit raw, followed in the 2013 Moscow Biennale.

Her tapestries carry the traditional chahar bagh structure and on closer scrutiny show battling creatures. It communicates the essence of a spiritual journey where dark forces coexist with beauty and ease with suffering – symbolised by a velvety surface and carefully inserted designs and gold-plated pins.

Khalid has used mirrors to paint and create a four-dimensional effect. Her work at the Venice Biennale 2009 “If you are everywhere you are nowhere, if you are somewhere you are everywhere” was a site specific installation at Mohatta Palace Museum Karachi in 2010. Her recent work for the 2018 Lahore Biennale at the Shahi Hamam was titled “More beautiful for having been broken.” Her latest commission at the newly opened Islamabad airport is dazzling.

Last year, Khalid with her husband Imran Qureshi, did the biggest show of her career in Pakistan “Two wings to fly not one.” After seeing the show Ustad Bashir Ahmed acknowledged that his student has taken the traditional art form taught by him to a new level. The Ustad’s prophecy about his student has come to fruition.

The writer can be reached at smt2104@caa.columbia.edu