Much time has passed since Faiz had said:

Once again the lamps will extinguish if the wind gathers speed

Better to bring a sun to the party: pay heed!

In the swift wind – or rather dark storm – of superstition, narrow-mindedness and prohibition, any attempt at lighting the lamp of freedom of opinion is welcome. Especially when that person’s very memory has the potential to infuriate opponents of free, critical thinking.

Admittedly, the tradition of freedom of thought is very ancient in Farsi and Urdu literature. But this freedom of expression was the preserve of poets alone. They would say whatever they liked against the powers of oppression and the constraints of rituals and restrictions, and nobody would object. And so, there is hardly a poet from Omar Khayyam and Hafez to Ghalib and Iqbal who has not challenged traditional ideas about the Divine, religion, Paradise, Hell, reward, punishment, Resurrection and tumult. And in doing so, these poets heaped satire and derision upon the censor and theologian, saint and mystic, preacher and zealot, magistrate and judge – those traditional figures of authority, conformity and punishment. But whenever any person of vision became a witness of truth in prose rather than poetry, they had to sacrifice their life – much like Hallaj and Sarmad.

Sir Syed was the first rationalist writer who raised the flag of freedom of opinion in the field of prose and obtained the ‘trophy’ of fatwas questioning his faith from his rivals. He made intellect his guide and evaluated our traditional beliefs and thoughts on the touchstone of modern knowledge. He privileged intellect over blind repetition and copying, rational interpretation of sacred texts over mere narration, ijtihad (innovation) over blind following and conducted his own jihad against the relentless ancestor-worship that plagued many Muslim thinkers of his time.

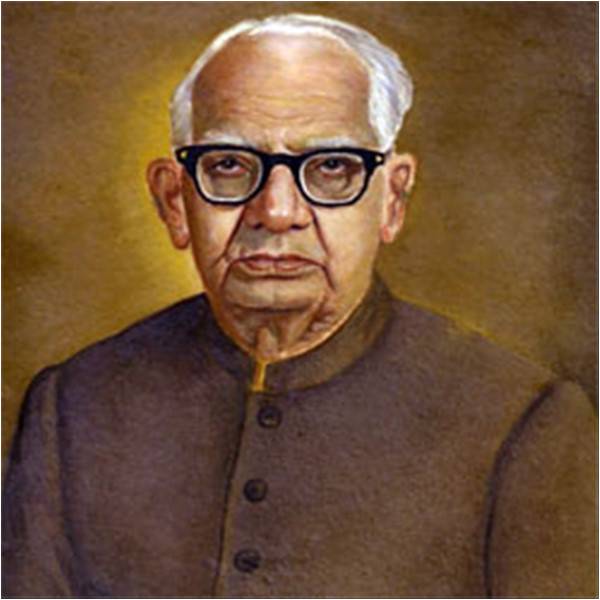

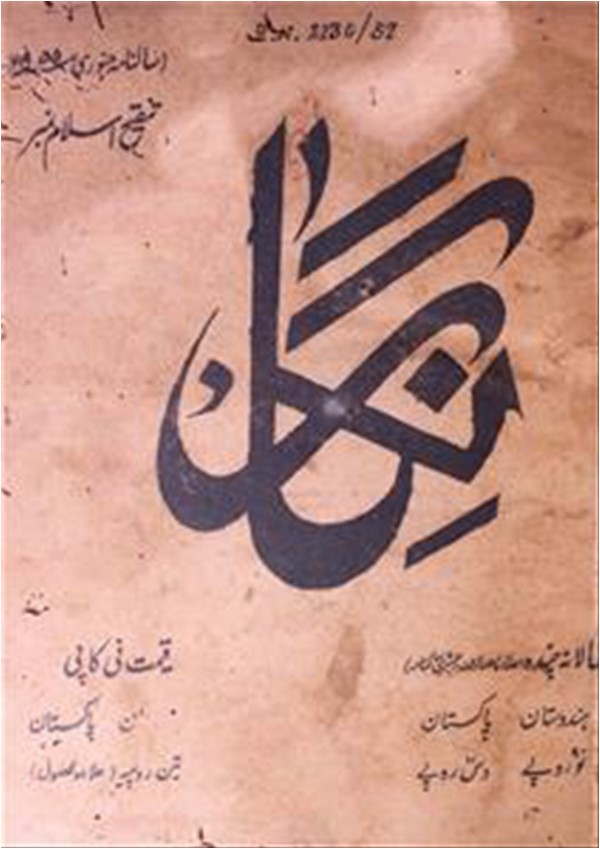

Following Sir Syed, the Urdu language produced many great intellectuals who awakened and illuminated our social consciousness. But the dedication and single-mindedness with which Allama Niaz Fatehpuri – who passed away in Karachi, 52 years ago on the 24th of May last month – carried forward the tradition of enlightenment from Sir Syed is unique. The intellectual training of whole generations is indebted to him and his journal Nigar. He played a historic role in freeing those generations from the spell of mullahism. Not for nothing does he share his death anniversary with another fellow critical thinker and ‘heretic’, the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus, who also passed away 475 years ago on the 24th of May – his book On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres demonstrating that the Earth moved around the Sun, an idea which was heretical for its time, and condemned by the Catholic Church.

The golden age of Niaz Fatehpuri and Nigar was the period between the First and Second World Wars. This period is also the time of our cultural renaissance when new capacities and perspectives appeared in the independence movement. Our social and literary values changed, and so did our taste and temperament. New waves of life sprang up in every branch of art and our aesthetic taste began to look for new directions. A determination sprang up to create a new world and a new kind of human. Niaz Fatehpuri was both a product of this renaissance and its symbol.

The late Maulvi Abdul Haq used to say that the Urdu language needs French Encyclopaedists like Rousseau, Voltaire and Diderot who can rid our minds of centuries of accumulated debris and reflect on our intellectual and societal problems in the light of knowledge.

Niaz Fatehpuri’s Encyclopaedist ability cannot be denied, but he was neither the Voltaire nor Rousseau of his time. And he did not, of course, have the capability to lead a revolutionary institution or movement.

But his contributions in the realm of free thought amongst Muslims are immense.

Like Allama Iqbal, Niaz Fatehpuri, too, considered mullahism to be a great impediment in the progress of freedom of thought. Mullahism for him does not belong to any particular country or religion, but it is a global intellectual condition – a manner of thought and action which relies on intimidation rather than rational arguments to have its beliefs accepted by others. It mixes the poison of fear within the hearts of the simple-minded and forces people to be obedient and submissive. It says that whatever had been written down long ago by scholars and theologians must be accepted without hesitation – even if it is very much against Reason. Arrogance and disdain are inherent to it. Its heart is bereft of feelings of love and sympathy. Finding a cure and sympathising is not its method. Instead of supporting the fallen, it serves them with kicks of curses and accusations, and shuts off all doors of reform and salvation by delivering fatwas of unbelief on the ‘misguided’. Niaz Fatehpuri writes:

“The term mullahism […] is the expression of a particular mentality which shuts the door of reason and understanding on the entire world except itself, and does not hesitate to fulfil its worst carnal motives using the excuse of religiosity by putting locks over people’s mind and judgement. This is a great demon which has spread countless deaths in the world from the dawn of Islam to the present day, of which the biggest death is the scattering of the binding of the national togetherness, making brother fight brother and separating the skin from the nail”

Niaz Fatehpuri was educated in Arabic madrasas. His principled opposition to obscurantism by religious authorities was a result of experiences with his teachers there. He says:

“My nature from the very beginning has been that I ponder over the reason and result of every matter and unless there is a valid reason, I can hardly accept anything. But when I presented my doubts before the teachers, apart from reproof and reproach, they did not give a satisfactory answer and always sought to silence me saying that to exercise reason in religion is the work of unbelievers and apostates […]”

This led him to wonder if he belonged to the same faith as his detractors!

He frequently expressed these same views openly in Nigar, but predictably, mullahism had no answer to the views of Niaz Fatehpuri except fatwas questioning his faith.

Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic and award-winning translator and dramatic reader currently teaching in Lahore. He is also the president of the Progressive Writers Association in Lahore. His most recent work is an introduction to the reissued edition (HarperCollins India, 2016) of Abdullah Hussein’s classic novel ‘The Weary Generations’. He can be reached at razanaeem@hotmail.com

Once again the lamps will extinguish if the wind gathers speed

Better to bring a sun to the party: pay heed!

In the swift wind – or rather dark storm – of superstition, narrow-mindedness and prohibition, any attempt at lighting the lamp of freedom of opinion is welcome. Especially when that person’s very memory has the potential to infuriate opponents of free, critical thinking.

Admittedly, the tradition of freedom of thought is very ancient in Farsi and Urdu literature. But this freedom of expression was the preserve of poets alone. They would say whatever they liked against the powers of oppression and the constraints of rituals and restrictions, and nobody would object. And so, there is hardly a poet from Omar Khayyam and Hafez to Ghalib and Iqbal who has not challenged traditional ideas about the Divine, religion, Paradise, Hell, reward, punishment, Resurrection and tumult. And in doing so, these poets heaped satire and derision upon the censor and theologian, saint and mystic, preacher and zealot, magistrate and judge – those traditional figures of authority, conformity and punishment. But whenever any person of vision became a witness of truth in prose rather than poetry, they had to sacrifice their life – much like Hallaj and Sarmad.

Sir Syed was the first rationalist writer who raised the flag of freedom of opinion in the field of prose and obtained the ‘trophy’ of fatwas questioning his faith from his rivals. He made intellect his guide and evaluated our traditional beliefs and thoughts on the touchstone of modern knowledge. He privileged intellect over blind repetition and copying, rational interpretation of sacred texts over mere narration, ijtihad (innovation) over blind following and conducted his own jihad against the relentless ancestor-worship that plagued many Muslim thinkers of his time.

Following Sir Syed, the Urdu language produced many great intellectuals who awakened and illuminated our social consciousness. But the dedication and single-mindedness with which Allama Niaz Fatehpuri – who passed away in Karachi, 52 years ago on the 24th of May last month – carried forward the tradition of enlightenment from Sir Syed is unique. The intellectual training of whole generations is indebted to him and his journal Nigar. He played a historic role in freeing those generations from the spell of mullahism. Not for nothing does he share his death anniversary with another fellow critical thinker and ‘heretic’, the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus, who also passed away 475 years ago on the 24th of May – his book On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres demonstrating that the Earth moved around the Sun, an idea which was heretical for its time, and condemned by the Catholic Church.

The golden age of Niaz Fatehpuri and Nigar was the period between the First and Second World Wars. This period is also the time of our cultural renaissance when new capacities and perspectives appeared in the independence movement. Our social and literary values changed, and so did our taste and temperament. New waves of life sprang up in every branch of art and our aesthetic taste began to look for new directions. A determination sprang up to create a new world and a new kind of human. Niaz Fatehpuri was both a product of this renaissance and its symbol.

The late Maulvi Abdul Haq used to say that the Urdu language needs French Encyclopaedists like Rousseau, Voltaire and Diderot who can rid our minds of centuries of accumulated debris and reflect on our intellectual and societal problems in the light of knowledge.

Niaz Fatehpuri’s Encyclopaedist ability cannot be denied, but he was neither the Voltaire nor Rousseau of his time. And he did not, of course, have the capability to lead a revolutionary institution or movement.

The intellectual training of whole generations is indebted to Niaz Fatehpuri and his journal Nigar

But his contributions in the realm of free thought amongst Muslims are immense.

Like Allama Iqbal, Niaz Fatehpuri, too, considered mullahism to be a great impediment in the progress of freedom of thought. Mullahism for him does not belong to any particular country or religion, but it is a global intellectual condition – a manner of thought and action which relies on intimidation rather than rational arguments to have its beliefs accepted by others. It mixes the poison of fear within the hearts of the simple-minded and forces people to be obedient and submissive. It says that whatever had been written down long ago by scholars and theologians must be accepted without hesitation – even if it is very much against Reason. Arrogance and disdain are inherent to it. Its heart is bereft of feelings of love and sympathy. Finding a cure and sympathising is not its method. Instead of supporting the fallen, it serves them with kicks of curses and accusations, and shuts off all doors of reform and salvation by delivering fatwas of unbelief on the ‘misguided’. Niaz Fatehpuri writes:

“The term mullahism […] is the expression of a particular mentality which shuts the door of reason and understanding on the entire world except itself, and does not hesitate to fulfil its worst carnal motives using the excuse of religiosity by putting locks over people’s mind and judgement. This is a great demon which has spread countless deaths in the world from the dawn of Islam to the present day, of which the biggest death is the scattering of the binding of the national togetherness, making brother fight brother and separating the skin from the nail”

Niaz Fatehpuri was educated in Arabic madrasas. His principled opposition to obscurantism by religious authorities was a result of experiences with his teachers there. He says:

“My nature from the very beginning has been that I ponder over the reason and result of every matter and unless there is a valid reason, I can hardly accept anything. But when I presented my doubts before the teachers, apart from reproof and reproach, they did not give a satisfactory answer and always sought to silence me saying that to exercise reason in religion is the work of unbelievers and apostates […]”

This led him to wonder if he belonged to the same faith as his detractors!

He frequently expressed these same views openly in Nigar, but predictably, mullahism had no answer to the views of Niaz Fatehpuri except fatwas questioning his faith.

Raza Naeem is a Pakistani social scientist, book critic and award-winning translator and dramatic reader currently teaching in Lahore. He is also the president of the Progressive Writers Association in Lahore. His most recent work is an introduction to the reissued edition (HarperCollins India, 2016) of Abdullah Hussein’s classic novel ‘The Weary Generations’. He can be reached at razanaeem@hotmail.com