The State cannot survive without the collection of sufficient taxes. Pakistan’s energy and water crises pose a greater threat to its existence than India or other, real or imagined, enemies. Yet the public discourse in Pakistan, particularly on television channels, is heavily focused on personalities and power politics. One major reason is that the so-called anchors have assumed the mantle of public intellectuals. Their fame has given them power which some have used to make fortunes.

A few mean rather well, but exercise self-censorship or are otherwise constrained by the business interests of their owners who place advertising revenues and ratings above anything else. This has left very little room for the discussion of the real issues that concern the people, for example, energy, water, and education. But all require mobilisation of resources (especially taxes) and Pakistan needs to mobilise these more than ever given that this is the worst economic crisis the country is facing since 1998. Given the proliferation of “breaking news” on the idiot box and video and audio clips on social media, the greatest casualty has been the quality of public discourse with serious implications for our collective political and social consciousness.

The Imran Khan phenomenon has made the public discourse even more binary and polarised. The truth is very few in the media, politics, or the establishment understand the complexity and gravity of Pakistan’s existential crises. It is not about civil-military tensions or perceived or real security threats from India or Afghanistan. Pakistan’s number one issue is the intellectual bankruptcy and short-sightedness of its military, political, business, media, and land owing elites. They need to understand that they can never have it so good anywhere else in the world because they won’t be able to compete.

Hence, it is in their supreme interest to make Pakistan a tenable state. Currently, it is a national security state that seems to have greatly stretched its ability to extract geo-strategic rents and is in a state of slow-motion implosion as a consequence of debilitating conflicts within the elite classes while about 78 percent of the population survives on $5.5 a day income and 40 percent of households suffer from moderate to severe food insecurity, according to the World Bank.

The Common Interests of Traditional Elites

No government in Pakistan has made a serious effort to mobilise domestic resources and reform the tax system. The parties make claims that are mostly misleading and hide the true picture. The reason is they are all part of a system that thrives on plundering the state resources and they are all in it. Malik Riaz’s case shows how intertwined class interests are. The media has been rocked by audio tapes which allegedly point to Riaz’s close links with Imran Khan and Zardari. Malik Riaz is one of the richest persons in Pakistan and owns Bahria Town, the largest privately held real estate development company in Pakistan. Riaz started as a clerk and became a multi-millionaire real estate developer with the full backing of the military. He also has had close ties with Nawaz Sharif’s family.

More than £190m of assets, including a £50m mansion overlooking Hyde Park in London, were seized from him after a settlement in a UK police “dirty money” investigation. Riaz had bought this mansion from Hasan Nawaz, Nawaz Sharif’s son, for £42.5 million in 2016. Malik Riaz is a microcosm of Pakistan’s real political economy where all the state institutions and major political actors act in concert to protect their class and corporate interests.

The Military Inc.

The military has ruled Pakistan, directly or indirectly, since 1977 and holds the real power. The first martial law in 1958 promised to eradicate corruption, but ended up institutionalising corruption with Ayub Khan’s family members becoming multi-millionaires.

According to a United Nations Development Program (UNDP) report, the military establishment owns the largest conglomerate of business entities in Pakistan, besides being the country’s biggest urban real estate developer and manager, with wide-ranging involvement in the construction of public projects. These functions often confer privileges to senior armed forces personnel, and enable the provision of extensive services, including healthcare and education, to the military’ s rank and file. In effect, the military establishment has emerged as a somewhat parallel structure to Pakistan’s civil governance institutions.

Pakistan’s military establishment essentially runs its business activities through two entities: the Fauji Foundation (FF) and the Army Welfare Trust (AWF). The Fauji Foundation is a conglomerate of four fully-owned companies and 21 associated companies. These operate in diverse industries and services, such as fertilizers, cement, food, power generation, gas exploration, liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) marketing and distribution, marine terminals, financial services, employment services, and security services.

The combined estimated value of these companies’ assets was RS 443 billion (US$2.64 billion) in 2017. These assets have grown rapidly, at a rate of over 13 percent per year.

In 2017, the Fauji Foundation’s net profits amounted to RS 33 billion, equivalent to a return of 6 percent on turnover. One-third of these profits are used to finance welfare activities for soldiers and their families. In addition, the military establishment runs foundations like Bahria and Shaheen. Askari Bank, owned by the military establishment, facilitates access to finance.

This medium-sized bank offers advances that total RS 284 billion, largely to Fauji Foundation companies. The interlocking of finance with industry has enhanced the competitive edge of these entities.

The Army Welfare Trust, formed in 1972, owns and operates 18 corporate entities. It has assets worth a total of RS 30 billion, and annual profits in the range of RS 2 billion. Currently, it provides almost 25,000 jobs. The Army Welfare Trust has sought an income tax exemption on the grounds that it is effectively a charitable institution that provides welfare services.

In terms of their economic role, Defence Housing Authorities (DHAs) are much bigger in scale than the Fauji Foundation or the Army Welfare Trust. Defence Housing Authorities operate in eight of Pakistan’s metropolitan cities: Karachi, Lahore, Islamabad–Rawalpindi, Bahawalpur, Gujranwala, Multan, and Quetta.

When the British colonised India, they built cantonment areas more or less on the periphery of major cities. Over the years, urban growth has led to many of these cantonment areas becoming centrally located.

The prime land they control has, for some time, been used for residential and commercial development. As such, low-density development activities in cantonment areas have pre-empted the emergence of central business districts in Pakistan’s major cities.

Cantonment boards, the mother entities of Defence Housing Authorities, enjoy two significant privileges. First, retail sales by outlets established by these boards are exempt from the 17 percent federal sales tax. In effect, all DHA residents enjoy this exemption. Clearly, this impacts the sales and profitability of retail outlets located outside of cantonment areas. Second, property tax collected in the DHAs is earmarked to the cantonment boards, which do not share these revenues with municipal or provincial governments. This is the case despite the fact that municipal and/or provincial governments provide trunk infrastructure to the DHAs. The revenue loss that results from these concessions has not been quantified due to a lack of data.

Residential land developed within the DHAs is initially allocated to members, a large number of whom are senior army personnel, usually in the officer cadre. Plot sizes range from eight marla (approximately 200 square yards) to four kanals (almost 2,000 square yards). Today, over 10,000 acres of land have been developed. However, no major low-cost housing schemes for non-commissioned personnel have been implemented in the DHAs.

The capital gains and rental income (net of depreciation) are conservatively valued at a rate of 11 percent of the property value on an annual basis. Therefore, the DHAs generate a total annual income of RS 170 billion, part of which accrues in the form of unrealised capital gains. This does not include the flow of income from commercial properties or the significant capital gains on vacant land.

The military’s other major role is as a contractor in public projects through the Frontier Works Organization (FWO). A large and vibrant construction firm, the organisation is engaged in the ongoing construction of highways, bridges, infrastructure, dams, and water supply projects. The estimated annual value of construction work by the organisation is RS 230 billion, yielding an annual net income of approximately RS 35 billion.

Furthermore, the National Logistics Cell (NLC) operates goods and transport vehicles, as well as undertakes construction activities. Information is not available on its net income.

The overall income generated from the military establishment’s economic activities was estimated at Rs257 billion in 2017–2018.

The taxation system benefits the elites at the cost of the overwhelming majority and is a major aspect of the dysfunctional political economy.

Trading Class

The retail sector in Pakistan has been amongst the fastest-growing markets, contributing almost 20% to the national GDP. It is the third-largest sector of the country and the second-highest employer, employing 15% of the labour force. With an estimated 2.8 million firms, traders have emerged as a powerful economic and civil society force in Pakistan. Committed to defending the interests of the traders, they are quick to mobilise and have resisted efforts to document the economy and pay their due share of taxes.

It is not all confrontation between traders and the state, however – on issues such as perceived affronts to Islam and national sovereignty, this same force comes out in strong support of state-sanctioned ideologies, allying itself with the military, Islamic forces, and political elites. Be it protests against the state’s purported intention to repeal blasphemy laws or against ‘Indian aggression’ and in explicit support of the Pakistan Army, for four decades now traders have been on the ‘right’ side of history and gaining organisational strength.

Sham Tax Reforms

The report of General Musharraf’s June 2000 Task Force on Reform of Tax Administration stated:

“Pakistan’s fiscal crisis is deep and cannot be easily resolved. Taxes are insufficient for debt service and defence. If the tax to GDP ratio does not increase significantly, Pakistan cannot be governed effectively, essential public services cannot be delivered and high inflation is inevitable. Reform of tax administration is the single most important economic task for the government.”

According to the World Bank, tax revenue collection as a share of GDP is only 15 to 20% in lower and middle-income countries but over 30% in upper-income countries. By this measure, Pakistan stands well behind even the developing countries.

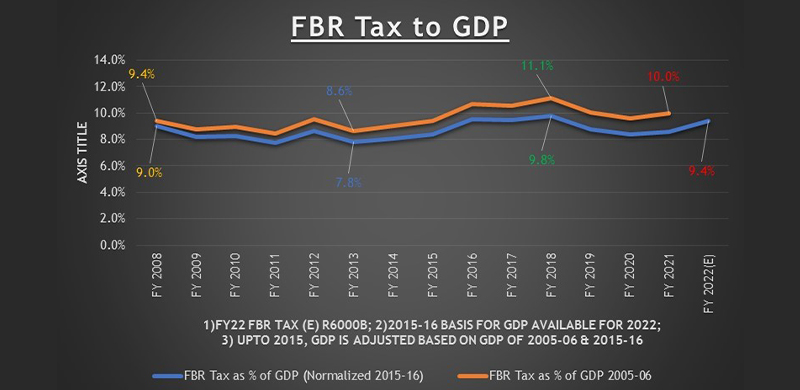

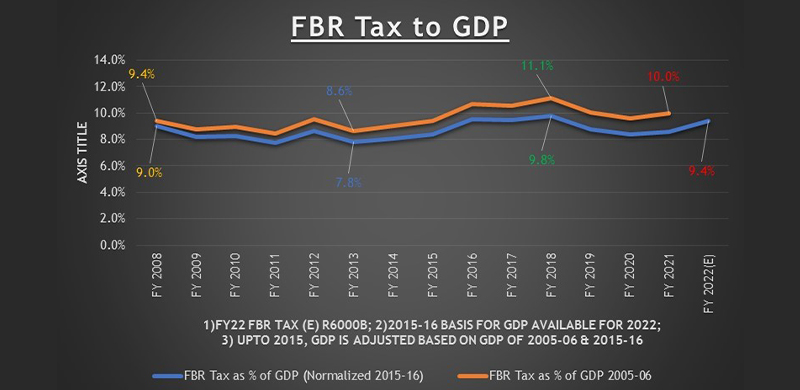

When General Musharraf left in 2008, Pakistan’s tax to GDP ratio was 9%. For the year ended 30 June 2021, it was 8.6%. For the tax year 2021, only 2.2 million (out of a population of 225.18 million) filed their income tax returns. Pakistan’s tax to GDP ratio is among the worst in the world and has not improved for a very long time.

The chart below shows the Federal Bureau of Revenue (FBR) tax collected to gross domestic product (GDP) ratio. Since the national accounts calculation methodology was revised to improve national income estimates with 2015-16 as the base year, the revised calculations have revealed a stark reality. Nothing much has changed over the longer period despite period to period variations.

Pakistan’s taxation system has one peculiar characteristic. The collection of income tax relies on withholding taxes for up to 70 percent of revenues. These taxes are mostly presumptive and fixed in nature. For example, income from interest is taxed as a separate block, at the fixed low rate of 10 percent. Clearly, this reduces the progressivity of the direct tax regime.

Sales tax represents the largest contribution to tax revenue in Pakistan, equivalent to 3.9 percent of GDP. The overall contribution by income tax (direct and indirect) is 3.7 percent of GDP. Combined, other indirect taxes – excluding the sales tax, as well as indirect and direct income tax – are equivalent to 4 percent of GDP.

Several characteristics of the indirect tax system need to be highlighted. First, there is heavy reliance on the taxation of petroleum products. These products contribute 37 percent to sales tax revenues and, overall, 25 percent to indirect tax revenues. Second, some basic food items – like sugar, edible oil, pulses, beverages, and tea, among others – are subject to different taxes. This causes the tax system to become regressive.

The agriculture sector is subject to income tax but only on paper. For example, Punjab’s provincial government collected just Rs2.5 billion from tax on agricultural income in 2020-21, which amounted to a negligible portion of its total revenue of Rs1.7 trillion. In Punjab, tax on agricultural income, land revenue, and property contributed an aggregate of just Rs33.5 billion or less than 2 percent of the total revenue receipts.

There is a need to identify the component of revenues from income tax which is derived from direct taxation, and the component which is derived from indirect taxation in de facto terms. The former consists of voluntary tax payments with returns, advance tax payments, demand raised after the audit of returns, advance tax on salaries, and taxation of unearned capital income. The indirect tax component includes presumptive taxes on contracts, imports, petroleum products, transport, electricity bills, and mobile phone cards. This component in some taxes accounts for the major part of revenues.

Why, What and How to Reform?

The current crisis demands that a political economy approach be adopted to expand the revenue base and cut budget deficits. The stakeholders need to appreciate that the current system is weakening the state, is regressive, inflationary, and unable to mobilise the resources needed to enable the state to perform its core functions of maintaining law and order and developing the infrastructure. In other words, it is in the interest of the large stakeholders that comprehensive tax reforms are introduced.

The history of tax reform around the world provides more than ample evidence that the single most important ingredient for effective tax administration is clear recognition at the highest levels of politics of the importance of the task and the willingness to support good administrative practices even if political friends are hurt in the short-term.

A recent report published by the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Pakistan is a damning indictment of both the state as well as the FBR. It stated:

“There have never been serious efforts made to widen the tax base. Most of the efforts failed simply because there was no political will of the government.”

I would add that the governments and the bureaucracy have worked collectively to mislead people.

Recently, the IMF and petrol prices have been the subject of hot and intensive political debates. Almost nobody highlights that eliminating subsidy on petrol was just one of the many points of the IMF program. The IMF country report 22/27 on Pakistan, published February 2022, recommends eliminating 2/3 of the subsidies given to the corporate sector through preferential sales tax rates. The IMF asked to “expand the number of removed exemptions (to the corporate sector) to include fertilizers and tractors, which constitute 23 percent of total sales tax subsidies.”

Low Rates and Few Exemptions

Many countries have benefited from the experience of East Asian countries and followed their policies. In Bolivia, a highly complicated tax system existed until 1985 with around 400 taxes and it had one of the highest rates of tax evasion in the Western hemisphere. The Tax Reform Law of 1985 repealed all the previous taxes and replaced them with seven new taxes. Some key common features of successful reform programmes have been as follows:

* The overall numbers of taxes are reduced to a dozen or less.

* Maximum rates are slashed as high rates have historically encouraged tax evasion.

* Rebates, exemptions and special treatments are eliminated or reduced to a few.

* Tax administration is simplified using technology.

High tax rates can force companies into the informal sector.

Digital Technology to Eliminate Bureaucratic Discretion and Facilitate Compliance

We need to introduce an integrated digital system through which record of interest and dividend payments by the financial institutions and companies to individuals would be linked to the tax system. There are at least 90 countries that have fully implemented electronic filing and payment of taxes.

In order to introduce a Digital Tax Regime, the National Tax Number should be the same as the CNIC number without the registration requirement and linked to the financial system through technology as in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada and Singapore and many other countries. At the end of every year, all interest or dividend paying institutions should be required to communicate total amount of such payments to everyone with the CNIC as the reference.

To ensure that the financial institutions have correct and valid mailing address, the delivery of cheque books or debit cards or any such payment instrument should not be allowed. This delivery must take place through the post. This small but critical detail would ensure that the addresses are correct. Proof of address is now a commonly used requirement to prevent money laundering and tax evasion. This measure would also lessen Pakistan's issues with the Financial Institutions Task Force (FATF)

All individuals with income greater than the minimum exemption limit should be required to file income tax return and include the details of interest and dividend payments received from the financial institutions. Since these details would already been communicated by the financial institutions to the Federal Board of Revenue, there would be no question of inaccurate reporting.

All tax assessments and correspondence should be available to the income tax filers online through a central portal maintained by the FBR. The FBR should communicate through post or electronic means and no physical presence of tax filers should be required except in the event of a criminal case.

These very simple but critical measures can dramatically increase tax collections and reduce corruption. There are nearly 55 million bank accounts, 10 million active bank loan customers and around 175 million mobile phone users in Pakistan. There is no reason that Pakistan's tax to GDP ratio of around 9 percent cannot be increased to catch up with that of other Asian countries. On the other hand, if we cannot attract foreign investments and fail to mobilise domestic resources, we would continue down the path we have been on for decades; a failing national security state that is sinking deeper into external debt with an increased risk of failure.

A few mean rather well, but exercise self-censorship or are otherwise constrained by the business interests of their owners who place advertising revenues and ratings above anything else. This has left very little room for the discussion of the real issues that concern the people, for example, energy, water, and education. But all require mobilisation of resources (especially taxes) and Pakistan needs to mobilise these more than ever given that this is the worst economic crisis the country is facing since 1998. Given the proliferation of “breaking news” on the idiot box and video and audio clips on social media, the greatest casualty has been the quality of public discourse with serious implications for our collective political and social consciousness.

The Imran Khan phenomenon has made the public discourse even more binary and polarised. The truth is very few in the media, politics, or the establishment understand the complexity and gravity of Pakistan’s existential crises. It is not about civil-military tensions or perceived or real security threats from India or Afghanistan. Pakistan’s number one issue is the intellectual bankruptcy and short-sightedness of its military, political, business, media, and land owing elites. They need to understand that they can never have it so good anywhere else in the world because they won’t be able to compete.

Hence, it is in their supreme interest to make Pakistan a tenable state. Currently, it is a national security state that seems to have greatly stretched its ability to extract geo-strategic rents and is in a state of slow-motion implosion as a consequence of debilitating conflicts within the elite classes while about 78 percent of the population survives on $5.5 a day income and 40 percent of households suffer from moderate to severe food insecurity, according to the World Bank.

The Common Interests of Traditional Elites

No government in Pakistan has made a serious effort to mobilise domestic resources and reform the tax system. The parties make claims that are mostly misleading and hide the true picture. The reason is they are all part of a system that thrives on plundering the state resources and they are all in it. Malik Riaz’s case shows how intertwined class interests are. The media has been rocked by audio tapes which allegedly point to Riaz’s close links with Imran Khan and Zardari. Malik Riaz is one of the richest persons in Pakistan and owns Bahria Town, the largest privately held real estate development company in Pakistan. Riaz started as a clerk and became a multi-millionaire real estate developer with the full backing of the military. He also has had close ties with Nawaz Sharif’s family.

More than £190m of assets, including a £50m mansion overlooking Hyde Park in London, were seized from him after a settlement in a UK police “dirty money” investigation. Riaz had bought this mansion from Hasan Nawaz, Nawaz Sharif’s son, for £42.5 million in 2016. Malik Riaz is a microcosm of Pakistan’s real political economy where all the state institutions and major political actors act in concert to protect their class and corporate interests.

The Military Inc.

The military has ruled Pakistan, directly or indirectly, since 1977 and holds the real power. The first martial law in 1958 promised to eradicate corruption, but ended up institutionalising corruption with Ayub Khan’s family members becoming multi-millionaires.

According to a United Nations Development Program (UNDP) report, the military establishment owns the largest conglomerate of business entities in Pakistan, besides being the country’s biggest urban real estate developer and manager, with wide-ranging involvement in the construction of public projects. These functions often confer privileges to senior armed forces personnel, and enable the provision of extensive services, including healthcare and education, to the military’ s rank and file. In effect, the military establishment has emerged as a somewhat parallel structure to Pakistan’s civil governance institutions.

The first martial law in 1958 promised to eradicate corruption, but ended up institutionalising corruption with Ayub Khan’s family members becoming multi-millionaires.

Pakistan’s military establishment essentially runs its business activities through two entities: the Fauji Foundation (FF) and the Army Welfare Trust (AWF). The Fauji Foundation is a conglomerate of four fully-owned companies and 21 associated companies. These operate in diverse industries and services, such as fertilizers, cement, food, power generation, gas exploration, liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) marketing and distribution, marine terminals, financial services, employment services, and security services.

The combined estimated value of these companies’ assets was RS 443 billion (US$2.64 billion) in 2017. These assets have grown rapidly, at a rate of over 13 percent per year.

In 2017, the Fauji Foundation’s net profits amounted to RS 33 billion, equivalent to a return of 6 percent on turnover. One-third of these profits are used to finance welfare activities for soldiers and their families. In addition, the military establishment runs foundations like Bahria and Shaheen. Askari Bank, owned by the military establishment, facilitates access to finance.

This medium-sized bank offers advances that total RS 284 billion, largely to Fauji Foundation companies. The interlocking of finance with industry has enhanced the competitive edge of these entities.

The Army Welfare Trust, formed in 1972, owns and operates 18 corporate entities. It has assets worth a total of RS 30 billion, and annual profits in the range of RS 2 billion. Currently, it provides almost 25,000 jobs. The Army Welfare Trust has sought an income tax exemption on the grounds that it is effectively a charitable institution that provides welfare services.

In terms of their economic role, Defence Housing Authorities (DHAs) are much bigger in scale than the Fauji Foundation or the Army Welfare Trust. Defence Housing Authorities operate in eight of Pakistan’s metropolitan cities: Karachi, Lahore, Islamabad–Rawalpindi, Bahawalpur, Gujranwala, Multan, and Quetta.

When the British colonised India, they built cantonment areas more or less on the periphery of major cities. Over the years, urban growth has led to many of these cantonment areas becoming centrally located.

The prime land they control has, for some time, been used for residential and commercial development. As such, low-density development activities in cantonment areas have pre-empted the emergence of central business districts in Pakistan’s major cities.

Cantonment boards, the mother entities of Defence Housing Authorities, enjoy two significant privileges. First, retail sales by outlets established by these boards are exempt from the 17 percent federal sales tax. In effect, all DHA residents enjoy this exemption. Clearly, this impacts the sales and profitability of retail outlets located outside of cantonment areas. Second, property tax collected in the DHAs is earmarked to the cantonment boards, which do not share these revenues with municipal or provincial governments. This is the case despite the fact that municipal and/or provincial governments provide trunk infrastructure to the DHAs. The revenue loss that results from these concessions has not been quantified due to a lack of data.

Residential land developed within the DHAs is initially allocated to members, a large number of whom are senior army personnel, usually in the officer cadre. Plot sizes range from eight marla (approximately 200 square yards) to four kanals (almost 2,000 square yards). Today, over 10,000 acres of land have been developed. However, no major low-cost housing schemes for non-commissioned personnel have been implemented in the DHAs.

The capital gains and rental income (net of depreciation) are conservatively valued at a rate of 11 percent of the property value on an annual basis. Therefore, the DHAs generate a total annual income of RS 170 billion, part of which accrues in the form of unrealised capital gains. This does not include the flow of income from commercial properties or the significant capital gains on vacant land.

The military’s other major role is as a contractor in public projects through the Frontier Works Organization (FWO). A large and vibrant construction firm, the organisation is engaged in the ongoing construction of highways, bridges, infrastructure, dams, and water supply projects. The estimated annual value of construction work by the organisation is RS 230 billion, yielding an annual net income of approximately RS 35 billion.

Furthermore, the National Logistics Cell (NLC) operates goods and transport vehicles, as well as undertakes construction activities. Information is not available on its net income.

The overall income generated from the military establishment’s economic activities was estimated at Rs257 billion in 2017–2018.

The taxation system benefits the elites at the cost of the overwhelming majority and is a major aspect of the dysfunctional political economy.

Trading Class

The retail sector in Pakistan has been amongst the fastest-growing markets, contributing almost 20% to the national GDP. It is the third-largest sector of the country and the second-highest employer, employing 15% of the labour force. With an estimated 2.8 million firms, traders have emerged as a powerful economic and civil society force in Pakistan. Committed to defending the interests of the traders, they are quick to mobilise and have resisted efforts to document the economy and pay their due share of taxes.

It is not all confrontation between traders and the state, however – on issues such as perceived affronts to Islam and national sovereignty, this same force comes out in strong support of state-sanctioned ideologies, allying itself with the military, Islamic forces, and political elites. Be it protests against the state’s purported intention to repeal blasphemy laws or against ‘Indian aggression’ and in explicit support of the Pakistan Army, for four decades now traders have been on the ‘right’ side of history and gaining organisational strength.

With an estimated 2.8 million firms, traders have emerged as a powerful economic and civil society force in Pakistan. Committed to defending the interests of the traders, they are quick to mobilise and have resisted efforts to document the economy and pay their due share of taxes.

Sham Tax Reforms

The report of General Musharraf’s June 2000 Task Force on Reform of Tax Administration stated:

“Pakistan’s fiscal crisis is deep and cannot be easily resolved. Taxes are insufficient for debt service and defence. If the tax to GDP ratio does not increase significantly, Pakistan cannot be governed effectively, essential public services cannot be delivered and high inflation is inevitable. Reform of tax administration is the single most important economic task for the government.”

According to the World Bank, tax revenue collection as a share of GDP is only 15 to 20% in lower and middle-income countries but over 30% in upper-income countries. By this measure, Pakistan stands well behind even the developing countries.

When General Musharraf left in 2008, Pakistan’s tax to GDP ratio was 9%. For the year ended 30 June 2021, it was 8.6%. For the tax year 2021, only 2.2 million (out of a population of 225.18 million) filed their income tax returns. Pakistan’s tax to GDP ratio is among the worst in the world and has not improved for a very long time.

The chart below shows the Federal Bureau of Revenue (FBR) tax collected to gross domestic product (GDP) ratio. Since the national accounts calculation methodology was revised to improve national income estimates with 2015-16 as the base year, the revised calculations have revealed a stark reality. Nothing much has changed over the longer period despite period to period variations.

Pakistan’s taxation system has one peculiar characteristic. The collection of income tax relies on withholding taxes for up to 70 percent of revenues. These taxes are mostly presumptive and fixed in nature. For example, income from interest is taxed as a separate block, at the fixed low rate of 10 percent. Clearly, this reduces the progressivity of the direct tax regime.

Sales tax represents the largest contribution to tax revenue in Pakistan, equivalent to 3.9 percent of GDP. The overall contribution by income tax (direct and indirect) is 3.7 percent of GDP. Combined, other indirect taxes – excluding the sales tax, as well as indirect and direct income tax – are equivalent to 4 percent of GDP.

Several characteristics of the indirect tax system need to be highlighted. First, there is heavy reliance on the taxation of petroleum products. These products contribute 37 percent to sales tax revenues and, overall, 25 percent to indirect tax revenues. Second, some basic food items – like sugar, edible oil, pulses, beverages, and tea, among others – are subject to different taxes. This causes the tax system to become regressive.

There is a need to identify the component of revenues from income tax which is derived from direct taxation, and the component which is derived from indirect taxation in de facto terms.

The agriculture sector is subject to income tax but only on paper. For example, Punjab’s provincial government collected just Rs2.5 billion from tax on agricultural income in 2020-21, which amounted to a negligible portion of its total revenue of Rs1.7 trillion. In Punjab, tax on agricultural income, land revenue, and property contributed an aggregate of just Rs33.5 billion or less than 2 percent of the total revenue receipts.

There is a need to identify the component of revenues from income tax which is derived from direct taxation, and the component which is derived from indirect taxation in de facto terms. The former consists of voluntary tax payments with returns, advance tax payments, demand raised after the audit of returns, advance tax on salaries, and taxation of unearned capital income. The indirect tax component includes presumptive taxes on contracts, imports, petroleum products, transport, electricity bills, and mobile phone cards. This component in some taxes accounts for the major part of revenues.

Why, What and How to Reform?

The current crisis demands that a political economy approach be adopted to expand the revenue base and cut budget deficits. The stakeholders need to appreciate that the current system is weakening the state, is regressive, inflationary, and unable to mobilise the resources needed to enable the state to perform its core functions of maintaining law and order and developing the infrastructure. In other words, it is in the interest of the large stakeholders that comprehensive tax reforms are introduced.

The history of tax reform around the world provides more than ample evidence that the single most important ingredient for effective tax administration is clear recognition at the highest levels of politics of the importance of the task and the willingness to support good administrative practices even if political friends are hurt in the short-term.

A recent report published by the Institute of Chartered Accountants of Pakistan is a damning indictment of both the state as well as the FBR. It stated:

“There have never been serious efforts made to widen the tax base. Most of the efforts failed simply because there was no political will of the government.”

I would add that the governments and the bureaucracy have worked collectively to mislead people.

Recently, the IMF and petrol prices have been the subject of hot and intensive political debates. Almost nobody highlights that eliminating subsidy on petrol was just one of the many points of the IMF program. The IMF country report 22/27 on Pakistan, published February 2022, recommends eliminating 2/3 of the subsidies given to the corporate sector through preferential sales tax rates. The IMF asked to “expand the number of removed exemptions (to the corporate sector) to include fertilizers and tractors, which constitute 23 percent of total sales tax subsidies.”

Low Rates and Few Exemptions

Many countries have benefited from the experience of East Asian countries and followed their policies. In Bolivia, a highly complicated tax system existed until 1985 with around 400 taxes and it had one of the highest rates of tax evasion in the Western hemisphere. The Tax Reform Law of 1985 repealed all the previous taxes and replaced them with seven new taxes. Some key common features of successful reform programmes have been as follows:

* The overall numbers of taxes are reduced to a dozen or less.

* Maximum rates are slashed as high rates have historically encouraged tax evasion.

* Rebates, exemptions and special treatments are eliminated or reduced to a few.

* Tax administration is simplified using technology.

High tax rates can force companies into the informal sector.

Digital Technology to Eliminate Bureaucratic Discretion and Facilitate Compliance

We need to introduce an integrated digital system through which record of interest and dividend payments by the financial institutions and companies to individuals would be linked to the tax system. There are at least 90 countries that have fully implemented electronic filing and payment of taxes.

In order to introduce a Digital Tax Regime, the National Tax Number should be the same as the CNIC number without the registration requirement and linked to the financial system through technology as in the United States, United Kingdom, Canada and Singapore and many other countries. At the end of every year, all interest or dividend paying institutions should be required to communicate total amount of such payments to everyone with the CNIC as the reference.

To ensure that the financial institutions have correct and valid mailing address, the delivery of cheque books or debit cards or any such payment instrument should not be allowed. This delivery must take place through the post. This small but critical detail would ensure that the addresses are correct. Proof of address is now a commonly used requirement to prevent money laundering and tax evasion. This measure would also lessen Pakistan's issues with the Financial Institutions Task Force (FATF)

All individuals with income greater than the minimum exemption limit should be required to file income tax return and include the details of interest and dividend payments received from the financial institutions. Since these details would already been communicated by the financial institutions to the Federal Board of Revenue, there would be no question of inaccurate reporting.

All tax assessments and correspondence should be available to the income tax filers online through a central portal maintained by the FBR. The FBR should communicate through post or electronic means and no physical presence of tax filers should be required except in the event of a criminal case.

These very simple but critical measures can dramatically increase tax collections and reduce corruption. There are nearly 55 million bank accounts, 10 million active bank loan customers and around 175 million mobile phone users in Pakistan. There is no reason that Pakistan's tax to GDP ratio of around 9 percent cannot be increased to catch up with that of other Asian countries. On the other hand, if we cannot attract foreign investments and fail to mobilise domestic resources, we would continue down the path we have been on for decades; a failing national security state that is sinking deeper into external debt with an increased risk of failure.