In 2009, when Brazil won the right to host Olympics in 2016, the then Brazilian president vowed to turn Rio de Janeiro (the city hosting Olympics) into the ‘capital of the world.’ This aim was to be achieved, not surprisingly, through heavy investment in infrastructure financed by public taxpayer money. The president also made another vow: to transform the lives of millions of poor people living in the city’s slums (favelas, as they are known in Brazil). The methodology for achieving that, at least in theory, is simple enough: heavy infrastructure development would generate jobs, and since a major portion of these jobs do not require high qualification - it is the poor who will get these jobs, and thus earn income that can change their lives.

In 2012, the final plan for the transformation was unveiled. Its cost came at a staggering $12 billion, the costliest in the history of Olympics. Rio’s mayor, while unveiling the plan, explicitly stated that without social integration, the investment would remain unfulfilled in its aims. What he meant was that unless the poorest benefit from this large infusion of capital, claims of ‘transformation’ will only remain just that.

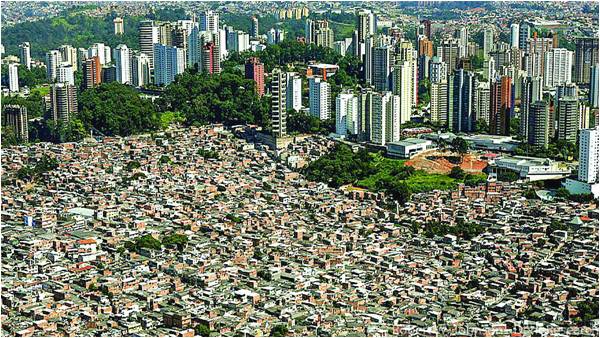

In 2016, when participants started to arrive for Olympics, they were greeted not by a transformed city, but by a stunning divide among its residents. They had entered a city which was more unequal than ever before (in terms of income and opportunities). The guests were left stunned by the sight of city’s policemen and fire-fighters holding placards that had ‘welcome to hell’ written on them. They had not been paid their salaries for months.

Things were even more precarious at the favelas, which the city’s mayor and others had envisioned as transformed, happy places at the time of the Olympics. In fact, at the time of the Olympics, the city’s mayor had to declare an emergency in these slums given the high rates of murders, suicides, drug peddling and other such grim socio-economic issues. To put things in perspective, these areas still lack any proper drainage system. The mayor said that the city’s finances were in the red, and they did not have any money to spend.

But where did the $12 billion go? This is no small amount. In fact, it is humongous given that majority of it (if not all) was national taxpayer money. Whatever was spent, who did it benefit the most? The city, its denizens, particular groups or some favoured individuals?

Enter Carlos Carvalho, a 92 year old (at that time) billionaire living in Rio. He is the owner of the most posh area of the city, known as Bara de Tijjuca, owning a total of 65 million square feet of property. This expensive locality houses a tiny fraction (300,000) of Rio’s estimated 12 million residents. Of the planned $12 billion ‘investment’, $3 billion alone was spent on constructing a subway extension to carry passengers from this area to other aristocratic, wealthy destinations like the beach spots of Leblon and Ipanema.

That was not all. The Athletes’ Village, the center piece of Olympics that was to house the athletes, was to be owned by Carvalho who was given permission to later convert the glitzy construction to luxury apartments. In short, a lot of the work was concentrated on either Carvalho’s owned places or near to them. No wonder that the end result was the sky rocketing rents in places which Carvalho owned.

The crux of the above narrated story goes like this: the government decides to undertake public work, financed by taxpayer money. The stated aim is to help the poor and transform their lives through these investments. But later it turns out that the major beneficiary were not the les miserable but the ones who already own the bigger slices of the economic pie, those who have connections at high places and have tons of money to spend around for buying minds and loyalties.

Redistribution of resources became a serious topic only in the 19th century economics. As the industrial revolution gathered steam, some astute observers noted the increasing pace of wealth concentration in the hands of a few groups. Charles Dickens, for example, lamented the sad state of children and labour in smoke laden towns of Britain. While the factories churned out product after product, the major portion of the wealth created from this process ended up in a few hands. Without going into details, this kind of division of fruits of labour fed indirectly into uprisings like that of 1840’s, which jolted Europe’s royal aristocracy. And it was this uneven distribution that gave rise to Marx and the popularity of his writings.

In the context of the above discussion, Pakistan is a poster child for adverse consequences of government-led resource redistribution. The examples and instances are countless, and would require a whole book to recount the consequences of those actions. For our purposes, the simple example of the agricultural lobby (especially sugar lobby) would suffice. Pick up any worthy research paper or report, the conclusion would be that it is only the landlords with large landholdings that are the main beneficiaries of these tax-payer financed subsidies. Of course, these are doled out in the name of helping the poor, who benefit the least (if at all) from these kinds of redistribution efforts.

In essence, subsidies like these are adverse or reverse redistribution, whereby financial resources are transferred from the poor and lower middle classes to the upper income classes. By any standard, this constitutes a crass use of government as a forum to take from one or two groups, and give it to those who need it the least.

Since Imran Khan’s government has now embarked upon some large scale redistribution programs (like building 50 million houses), it is imperative that lessons are learnt from the previous episodes. For any worthy effort over redistribution of resources, there needs to be some very good planning and an excellent governance structure that ensures the direction of distribution is from the top tiers to the lower ones.

Unfortunately, Pakistan’s history tells us something else. Imran Khan and his team must be cognizant of this fact, especially focusing on those channels and lobbies that turn the redistribution efforts adverse. All of PTIs efforts, if they are to prove a success, would have to be based on an excellent governance structure. That implies, above all, that governance reforms are a pre-requisite for success of any resource re-distribution effort.

The writer is an economist

In 2012, the final plan for the transformation was unveiled. Its cost came at a staggering $12 billion, the costliest in the history of Olympics. Rio’s mayor, while unveiling the plan, explicitly stated that without social integration, the investment would remain unfulfilled in its aims. What he meant was that unless the poorest benefit from this large infusion of capital, claims of ‘transformation’ will only remain just that.

In 2016, when participants started to arrive for Olympics, they were greeted not by a transformed city, but by a stunning divide among its residents. They had entered a city which was more unequal than ever before (in terms of income and opportunities). The guests were left stunned by the sight of city’s policemen and fire-fighters holding placards that had ‘welcome to hell’ written on them. They had not been paid their salaries for months.

Things were even more precarious at the favelas, which the city’s mayor and others had envisioned as transformed, happy places at the time of the Olympics. In fact, at the time of the Olympics, the city’s mayor had to declare an emergency in these slums given the high rates of murders, suicides, drug peddling and other such grim socio-economic issues. To put things in perspective, these areas still lack any proper drainage system. The mayor said that the city’s finances were in the red, and they did not have any money to spend.

But where did the $12 billion go? This is no small amount. In fact, it is humongous given that majority of it (if not all) was national taxpayer money. Whatever was spent, who did it benefit the most? The city, its denizens, particular groups or some favoured individuals?

Enter Carlos Carvalho, a 92 year old (at that time) billionaire living in Rio. He is the owner of the most posh area of the city, known as Bara de Tijjuca, owning a total of 65 million square feet of property. This expensive locality houses a tiny fraction (300,000) of Rio’s estimated 12 million residents. Of the planned $12 billion ‘investment’, $3 billion alone was spent on constructing a subway extension to carry passengers from this area to other aristocratic, wealthy destinations like the beach spots of Leblon and Ipanema.

That was not all. The Athletes’ Village, the center piece of Olympics that was to house the athletes, was to be owned by Carvalho who was given permission to later convert the glitzy construction to luxury apartments. In short, a lot of the work was concentrated on either Carvalho’s owned places or near to them. No wonder that the end result was the sky rocketing rents in places which Carvalho owned.

The crux of the above narrated story goes like this: the government decides to undertake public work, financed by taxpayer money. The stated aim is to help the poor and transform their lives through these investments. But later it turns out that the major beneficiary were not the les miserable but the ones who already own the bigger slices of the economic pie, those who have connections at high places and have tons of money to spend around for buying minds and loyalties.

Redistribution of resources became a serious topic only in the 19th century economics. As the industrial revolution gathered steam, some astute observers noted the increasing pace of wealth concentration in the hands of a few groups. Charles Dickens, for example, lamented the sad state of children and labour in smoke laden towns of Britain. While the factories churned out product after product, the major portion of the wealth created from this process ended up in a few hands. Without going into details, this kind of division of fruits of labour fed indirectly into uprisings like that of 1840’s, which jolted Europe’s royal aristocracy. And it was this uneven distribution that gave rise to Marx and the popularity of his writings.

In the context of the above discussion, Pakistan is a poster child for adverse consequences of government-led resource redistribution. The examples and instances are countless, and would require a whole book to recount the consequences of those actions. For our purposes, the simple example of the agricultural lobby (especially sugar lobby) would suffice. Pick up any worthy research paper or report, the conclusion would be that it is only the landlords with large landholdings that are the main beneficiaries of these tax-payer financed subsidies. Of course, these are doled out in the name of helping the poor, who benefit the least (if at all) from these kinds of redistribution efforts.

In essence, subsidies like these are adverse or reverse redistribution, whereby financial resources are transferred from the poor and lower middle classes to the upper income classes. By any standard, this constitutes a crass use of government as a forum to take from one or two groups, and give it to those who need it the least.

Since Imran Khan’s government has now embarked upon some large scale redistribution programs (like building 50 million houses), it is imperative that lessons are learnt from the previous episodes. For any worthy effort over redistribution of resources, there needs to be some very good planning and an excellent governance structure that ensures the direction of distribution is from the top tiers to the lower ones.

Unfortunately, Pakistan’s history tells us something else. Imran Khan and his team must be cognizant of this fact, especially focusing on those channels and lobbies that turn the redistribution efforts adverse. All of PTIs efforts, if they are to prove a success, would have to be based on an excellent governance structure. That implies, above all, that governance reforms are a pre-requisite for success of any resource re-distribution effort.

The writer is an economist