From Argentina to Kashmir, and Sri Lanka to Syria, wherever in the world the states have forcibly disappeared men — their mothers, daughters, wives, sisters have come out to fight for their release and Pakistan is no different. The Baloch, Sindhi, Pashtun, Shia and now Punjabi women have had to seek truth, justice and accountability for their loved ones, and are Pakistan’s staunch defenders of human rights. Based in Rawalpindi, Islamabad, Karachi, Larkana and Quetta, the tireless advocacy of these women is why Pakistanis understand what an enforced disappearance is, how this crime violates human dignity and terrorizes families. Per international human rights law, families of the disappeared are also victims of the crime of enforced disappearance. Despite the threats, harassment, false police cases, use of force and surveillance, delay in justice, and the debilitating uncertainty, the women from the families of the disappeared have refused to cede space to the perpetrators and to the state apparatus trampling on their rights.

The Friday Times spoke to the women human rights defenders who are at the frontlines of the war against enforced disappearances for the International Women’s Day.

Amina Masood Janjua

Amina Masood Janjua is Asia’s foremost campaigner against the crime of enforced disappearances. She set up the Defence of Human Rights Pakistan (DHR), a non-profit trust, to help families of the disappeared and formalise advocacy around the release of victims. Her husband Ahmad Masood Janjua, forcibly disappeared in 2005 from Rawalpindi, is one of the emblematic cases of this crime. It was an era when the stigma, shame and misinformation tied to enforced disappearances was extreme. Initially struggling with her loss and grief, Amina slowly began showing up for protests. Upon seeing the pain of the other families lacking resources and a platform to seek or access justice, Amina started guiding them and found her calling.

Since then, Amina has been subjected to the use of force, arrested, harassed and her children targeted for peaceful protests. But Amina has kept going and never withdrew once from the campaign. DHR has documented hundreds of disappearances, helped families get to the courts, organized civic action, extended solidarity and collaborated with victim groups and even advocated against this brutality globally. A former art major, a stay-at-home mother, Amina is now a trained lawyer and currently amicus curiae in an on-going case of disappearance victims at the Islamabad High Court.

“Had I not consistently associated with [other victim] families, I would have drowned in hopelessness and depression and would have broken down. Whenever a victim is released, the relief and tears of the family members give me the strength to keep me going. My mission is to continue working for the separated families of the disappeared to reunite.”

Dr Mahrang Baloch

Ten years ago, Mahrang Baloch moved to Quetta from her hometown of Mangochar, Kalat with the dream of becoming a doctor, and is now finishing her FCPS in surgery. A graduate of Bolan Medical College, she sees her medical service as a form of activism. However, the road to achieve this dream, that the politically conscious Mahrang shares with her late father, was lined with horrors and hardships. Her, father nationalist political dissident Abdul Ghaffar Lango, was forcibly disappeared first in 2006 and then in 2009, before his extrajudicial killing in 2011. She was 16 when Lango’s body bearing torture marks was found in Gadani. Mahrang had to renew her participation in the Baloch movement for missing persons when her brother Nasir Baloch was subjected to enforced disappearance for more than three months in 2017. The fear of losing another loved one to state violence also made her set-up a Twitter account. “My first tweet was for the release of my only brother,” she said. She has not stopped demonstrating for justice since then despite the threats and risks.

She has also organized against the harassment of women students in University of Balochistan. Mahrang told TFT it is difficult to avoid professional discrimination and maintain political activism, “we live in a society where people are ignorant of their human and political rights. So those of us who are politically active are isolated, and our intellect and professional capability is continuously seen with suspicion and undermined.”

Sammi Deen

Sammi Deen has led the protests of families and not been afraid to confront the police rounding up of Baloch men and women from protest sites. She was a child when, in 2009, her father Dr Deen Muhammad, a doctor and Baloch nationalist leader, was forcibly picked up. Sammi and her family were forced into displacement from Mashkay, Awaran to Karachi due to military operations, the occupation of their home by security forces, safety of her brother and her mother’s well-being. The life of an activist was also forced on her as a victim family member, she says. As a daughter seeking answers and release of her father, she has remained in the state of protest for 14 years, but now Sammi, 25, has taken up a formal role with the Voice of Baloch Missing Persons (VBMP), “It was not an easy choice. I am the patriarch of my family, its mard, and the primary care provider for my mother, and follow up on my father’s case. But due to questions from other women relatives about pursuing cases, I decided to take up this responsibility.”

Sammi, a media science student, has engaged with government bodies and commissions for the recovery of the Baloch forcibly disappeared, and taken her cause to national platforms. She is undeterred by the arbitrary detentions, law enforcement agencies’ batons and teargas shelling, and surveillance. Due to the enormous scale of Baloch targeting through enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings, Baloch women family members of the disappeared have not only carried forward the campaign against these abuses, but have also inspired solidarity from other victim groups.

Sorath Lohar

Sorath Lohar, with her sister Sasui, started marching for their father’s release and went to the court for justice, when he was forcibly disappeared in 2017. Even after the release of their Sindhi nationalist father Hidayat Lohar in 2019, Sorath and her sister not only fearlessly led the campaign for the Sindhi forcibly disappeared but also collaborated with other affected groups’ including the Shia, Baloch and families of the MQM’s disappeared during sit-ins and strike camps in Karachi. Sorath, 31, a lawyer by training, is also engaged in documentation of Sindhi missing from the platform of a collective for Sindhi forcibly disappeared and advocated to shed light on their plight on global forums. For her advocacy, Sorath is continuously on the receiving end of the security forces’ ire, who have rolled out a slew of unproven accusations against her.

The harassment and surveillance has continued even after she got married, in the form of pressure on in-laws. A press release from CTD Hyderabad dated February 15 about an “intelligence-based operation” and arrest of suspected miscreants, named her and another human rights activist as abettors and handlers of terrorists. She sat with HRCP Karachi at the press club and went public with her harassment. “Instead of defaming us and hurling allegations, the Sindhi activists, engaged in demanding release of the Sindhi missing persons, the CTD must come forward with evidence. How can the authorities accuse separatists when all our movement and activism is in the public eye?”

Rahat Mahmood

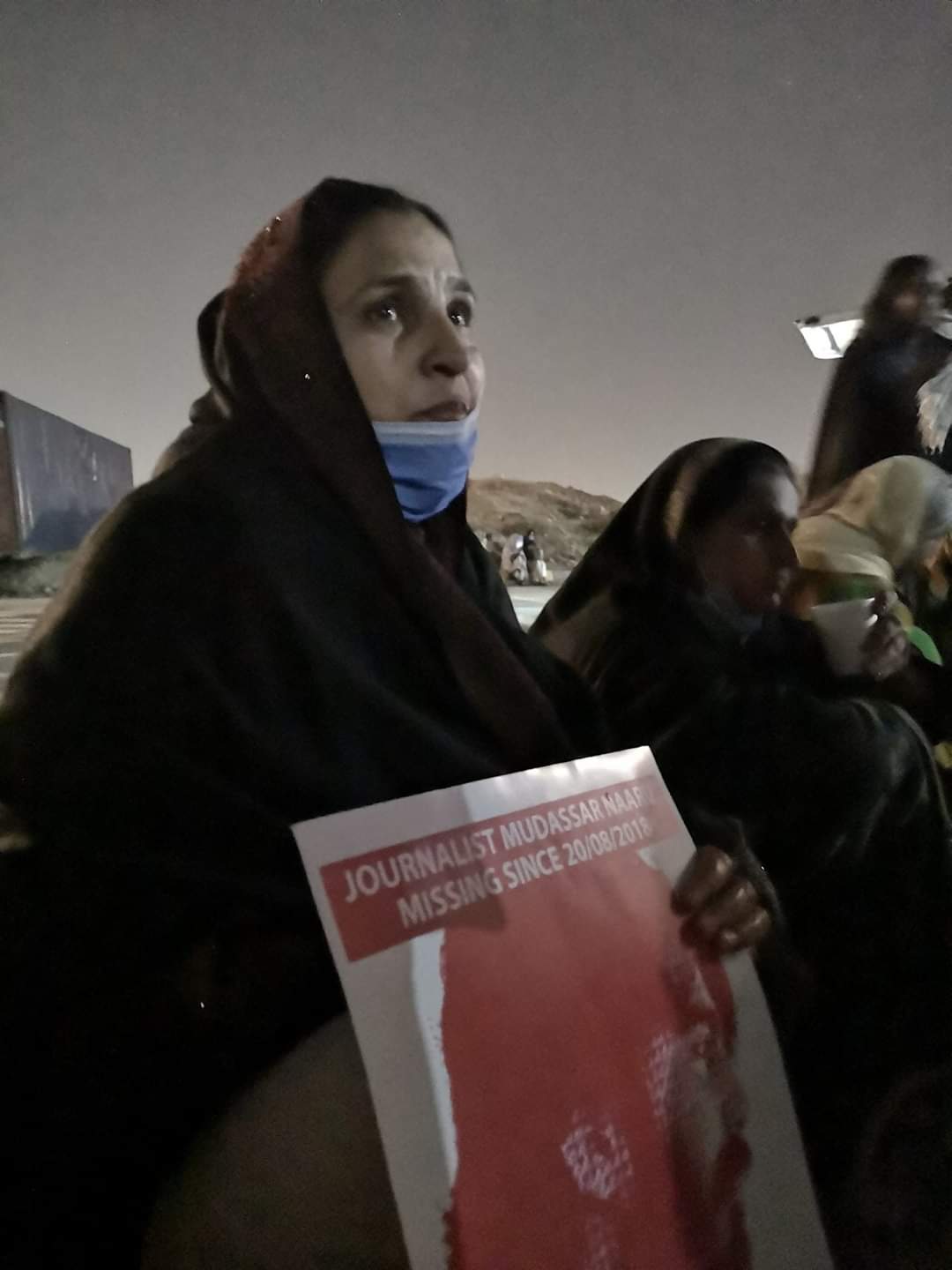

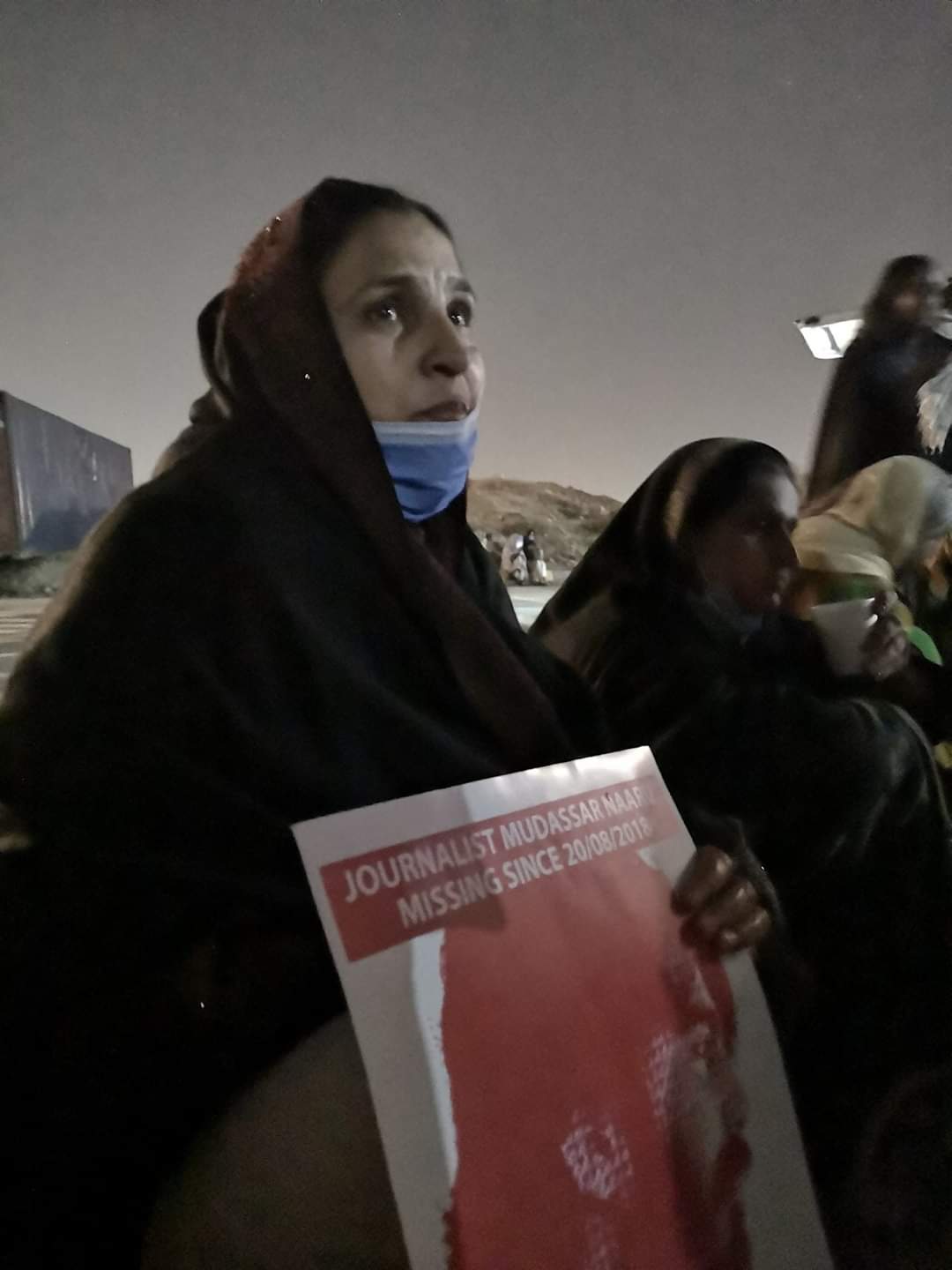

In winter of 2021, when the Baloch families took their sit-in to Islamabad, Mrs Rahat Mahmood’s eldest son told her, “Ammi, the mothers are sitting in Islamabad”. She took her placards with her Punjabi progressive poet and journalist Mudassar Mahmood Naaru’s photos and joined the Baloch mothers. It was the first protest she participated in by herself, but she has been active since. Last year in Faisalabad she spoke out and demonstrated for the release of student Hafeez Baloch who was forcibly disappeared from Balochistan. A former healthcare worker, and resident of Chak No. 219/RB Tallianwala in Faisalabad, Mrs. Rahat took a more active role in campaigning for her son when his wife Sadaf Chughtai passed away in May 2021.

For a year, she has also appeared diligently before Islamabad High Court with her 5-year-old grandson Sachal. Both are waiting for Naaru whose whereabouts and fate have remained unknown since August 2018. She has met with the government constituted commission, in the court last year, PM Sharif, and explores all avenues of redress. Each delay in the IHC hearing of Naaru’s case is a “defeat” for Mrs Rahat, “I think of people who take their lives when the status quo does not change and they want to take a drastic action. I can understand their hopelessness and feel suffocated. I, too, want to march to the GHQ and to Islamabad, and put soil in my head and face to protest till my son is released.”

The Friday Times spoke to the women human rights defenders who are at the frontlines of the war against enforced disappearances for the International Women’s Day.

Amina Masood Janjua

Amina Masood Janjua is Asia’s foremost campaigner against the crime of enforced disappearances. She set up the Defence of Human Rights Pakistan (DHR), a non-profit trust, to help families of the disappeared and formalise advocacy around the release of victims. Her husband Ahmad Masood Janjua, forcibly disappeared in 2005 from Rawalpindi, is one of the emblematic cases of this crime. It was an era when the stigma, shame and misinformation tied to enforced disappearances was extreme. Initially struggling with her loss and grief, Amina slowly began showing up for protests. Upon seeing the pain of the other families lacking resources and a platform to seek or access justice, Amina started guiding them and found her calling.

Since then, Amina has been subjected to the use of force, arrested, harassed and her children targeted for peaceful protests. But Amina has kept going and never withdrew once from the campaign. DHR has documented hundreds of disappearances, helped families get to the courts, organized civic action, extended solidarity and collaborated with victim groups and even advocated against this brutality globally. A former art major, a stay-at-home mother, Amina is now a trained lawyer and currently amicus curiae in an on-going case of disappearance victims at the Islamabad High Court.

“Had I not consistently associated with [other victim] families, I would have drowned in hopelessness and depression and would have broken down. Whenever a victim is released, the relief and tears of the family members give me the strength to keep me going. My mission is to continue working for the separated families of the disappeared to reunite.”

Dr Mahrang Baloch

Ten years ago, Mahrang Baloch moved to Quetta from her hometown of Mangochar, Kalat with the dream of becoming a doctor, and is now finishing her FCPS in surgery. A graduate of Bolan Medical College, she sees her medical service as a form of activism. However, the road to achieve this dream, that the politically conscious Mahrang shares with her late father, was lined with horrors and hardships. Her, father nationalist political dissident Abdul Ghaffar Lango, was forcibly disappeared first in 2006 and then in 2009, before his extrajudicial killing in 2011. She was 16 when Lango’s body bearing torture marks was found in Gadani. Mahrang had to renew her participation in the Baloch movement for missing persons when her brother Nasir Baloch was subjected to enforced disappearance for more than three months in 2017. The fear of losing another loved one to state violence also made her set-up a Twitter account. “My first tweet was for the release of my only brother,” she said. She has not stopped demonstrating for justice since then despite the threats and risks.

She has also organized against the harassment of women students in University of Balochistan. Mahrang told TFT it is difficult to avoid professional discrimination and maintain political activism, “we live in a society where people are ignorant of their human and political rights. So those of us who are politically active are isolated, and our intellect and professional capability is continuously seen with suspicion and undermined.”

Sammi Deen

Sammi Deen has led the protests of families and not been afraid to confront the police rounding up of Baloch men and women from protest sites. She was a child when, in 2009, her father Dr Deen Muhammad, a doctor and Baloch nationalist leader, was forcibly picked up. Sammi and her family were forced into displacement from Mashkay, Awaran to Karachi due to military operations, the occupation of their home by security forces, safety of her brother and her mother’s well-being. The life of an activist was also forced on her as a victim family member, she says. As a daughter seeking answers and release of her father, she has remained in the state of protest for 14 years, but now Sammi, 25, has taken up a formal role with the Voice of Baloch Missing Persons (VBMP), “It was not an easy choice. I am the patriarch of my family, its mard, and the primary care provider for my mother, and follow up on my father’s case. But due to questions from other women relatives about pursuing cases, I decided to take up this responsibility.”

Sammi, a media science student, has engaged with government bodies and commissions for the recovery of the Baloch forcibly disappeared, and taken her cause to national platforms. She is undeterred by the arbitrary detentions, law enforcement agencies’ batons and teargas shelling, and surveillance. Due to the enormous scale of Baloch targeting through enforced disappearances and extrajudicial killings, Baloch women family members of the disappeared have not only carried forward the campaign against these abuses, but have also inspired solidarity from other victim groups.

Sorath Lohar

Sorath Lohar, with her sister Sasui, started marching for their father’s release and went to the court for justice, when he was forcibly disappeared in 2017. Even after the release of their Sindhi nationalist father Hidayat Lohar in 2019, Sorath and her sister not only fearlessly led the campaign for the Sindhi forcibly disappeared but also collaborated with other affected groups’ including the Shia, Baloch and families of the MQM’s disappeared during sit-ins and strike camps in Karachi. Sorath, 31, a lawyer by training, is also engaged in documentation of Sindhi missing from the platform of a collective for Sindhi forcibly disappeared and advocated to shed light on their plight on global forums. For her advocacy, Sorath is continuously on the receiving end of the security forces’ ire, who have rolled out a slew of unproven accusations against her.

The harassment and surveillance has continued even after she got married, in the form of pressure on in-laws. A press release from CTD Hyderabad dated February 15 about an “intelligence-based operation” and arrest of suspected miscreants, named her and another human rights activist as abettors and handlers of terrorists. She sat with HRCP Karachi at the press club and went public with her harassment. “Instead of defaming us and hurling allegations, the Sindhi activists, engaged in demanding release of the Sindhi missing persons, the CTD must come forward with evidence. How can the authorities accuse separatists when all our movement and activism is in the public eye?”

Rahat Mahmood

In winter of 2021, when the Baloch families took their sit-in to Islamabad, Mrs Rahat Mahmood’s eldest son told her, “Ammi, the mothers are sitting in Islamabad”. She took her placards with her Punjabi progressive poet and journalist Mudassar Mahmood Naaru’s photos and joined the Baloch mothers. It was the first protest she participated in by herself, but she has been active since. Last year in Faisalabad she spoke out and demonstrated for the release of student Hafeez Baloch who was forcibly disappeared from Balochistan. A former healthcare worker, and resident of Chak No. 219/RB Tallianwala in Faisalabad, Mrs. Rahat took a more active role in campaigning for her son when his wife Sadaf Chughtai passed away in May 2021.

For a year, she has also appeared diligently before Islamabad High Court with her 5-year-old grandson Sachal. Both are waiting for Naaru whose whereabouts and fate have remained unknown since August 2018. She has met with the government constituted commission, in the court last year, PM Sharif, and explores all avenues of redress. Each delay in the IHC hearing of Naaru’s case is a “defeat” for Mrs Rahat, “I think of people who take their lives when the status quo does not change and they want to take a drastic action. I can understand their hopelessness and feel suffocated. I, too, want to march to the GHQ and to Islamabad, and put soil in my head and face to protest till my son is released.”