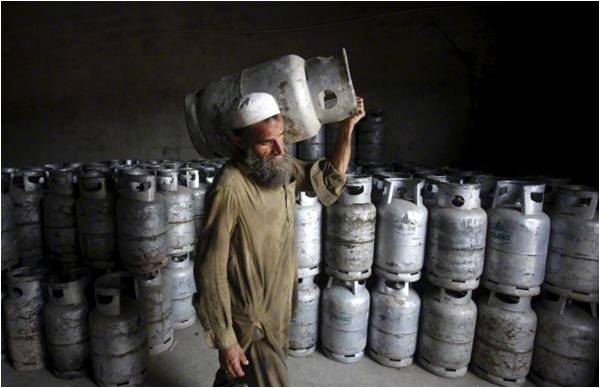

From stoves in homes and cars on the streets, to textile factories employing a substantial urban workforce, companies producing affordable fertilizer, and power plants – natural gas plays an immense role in Pakistan’s economy.

In that backdrop, the month of March was a watershed. It marked the beginning of gas imports into Pakistan. But instead of being a moment to cheer about, it has become another example of bad execution, poor governance and myopic policy.

The idea to import gas is not new. Successive governments have mulled over it for at least 10 years. Yet, what has happened with the first liquefied natural gas (LNG) import terminal is a reflection of how the energy issue has been handled in past.

For more than 57 years, the country has drilled holes in ground to suck out this hydrocarbon, exploiting an area stretching from the barren land of Balochistan’s Dera Bugti to the Gambat South Block in Sindh, and all the way up to Tal in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

As a result, a zigzagging web of pipelines was laid across the country – put together that’s more than 165,000 kilometers. Gas was everywhere and for everyone.

Long considered to be an abundant indigenous resource unlike oil, which was imported, its price was kept below international level for so many years that households and commercial users started to take it for granted. The result of this exploitation has been that among all the sources of energy fueling the country, natural gas has a share of 50 percent.

Effort was made to spur domestic gas output through new policies, which offered better return to petroleum exploration and production companies. But production has remained stagnant at 4,000 million cubic feet per day (MMCFD). Demand, on the other hand, has soared beyond 6,000 MMCFD.

Gas shortage has also compounded the electricity crisis. Back in the 1990s when the private sector was encouraged to invest in building thermal power plants, most of them were based on furnace oil because its price at Rs12,000 per ton was not a big deal.

But the folly of this decision became obvious within a few years after the oil price skyrocketed. As a result, power generation on gas was encouraged and the power sector gradually became one of largest gas consumers.

In 2010, gas accounted for 55 percent of thermal electricity being generated, while the remaining plants used furnace oil and diesel. By 2014 the ratio had reversed to 39 percent, because more and more of gas was being diverted to domestic consumers because of the shortage.

An attempt to counter this situation by importing gas import had begun in earnest in 2005. Everyone knew that importing gas via a pipeline from Iran was not possible because of Tehran’s confrontation with world powers.

Lengthy studies and negotiations on the Mashal LNG Project went on for several years. When the project was finally awarded, the apex court struck it down on charges of bad governance. Work on other LNG terminals also started. However none made it beyond the drawing board.

Then in 2014, Engro Corporation won the bid to build an LNG terminal. The project involved a large ship known as FSRU (floating storage and regasification unit), which has onboard storage tanks and a processing plant to convert super-chilled liquid methane back into gaseous form.

Sheikh Imran ul Haque, who looks after Engro’s chemical business, was tasked to ensure that the terminal becomes operational on time. He and his team were able to develop physical infrastructure which involved a jetty and pipeline and complete complex and lengthy negotiations within a record 11 months. But even before the FSRU anchored at Port Qasim, problems had started to emerge.

Engro, as operator of the terminal, is responsible for receiving LNG shipments and pass them on to the national pipeline grid. For this service, it is entitled to receive $272,000 per day as a capacity charge even if not a single molecule of gas goes through its system.

The government has taken upon itself to arrange and import gas. Considering the costs associated with leaving the terminal unused, policymakers should have arranged regular import shipments. However, the so-called government-to-government deal with Qatar hasn’t worked the way it was supposed to. The FSRU that anchored in last week of March brought along 3,000 MMCF of gas. That was a stopgap arrangement to save face. Petroleum Minister Shahid Khaqan Abbasi was quick to suggest that the cargo was imported and paid for by the private sector.

“The first consignment was booked by Pakistan State Oil (PSO). Qataris would only deal with PSO, which had to open a Rs3.2 billion letter of credit in their favor,” said an industry official who used to oversee energy supply chain.

This should have been a straightforward affair: imported gas comes into the system, increasing the available supply, which is distributed at a decided price among industrial consumers desperately in need. But that’s not the case.

When officials say that LNG will be used to run power plants located in Punjab, it doesn’t mean that gas will be delivered in some dedicated pipeline all the way from the port in Karachi. As a matter of fact, imported gas is being distributed among bulk consumers scattered near Port Qasim’s vicinity. This is specifically being done to avoid wastage which occurs due to pipeline leakages and theft.

But somehow, the price difference has to be made up for. After all, the price of imported gas at $12.5 per unit is much more than the existing average consumer price of just $4. And this is where the complex regulatory structure comes into play and makes things worse.

Consumer gas price is determined by the Oil and Gas Regulatory Authority (Ogra). Private parties who will ultimately have to pay for the first LNG consignment are fertilizer producers, which buy gas from the two utilities –SSGC and SNGPL – at a subsidized price. The issue is not the higher price they have to pay, but how they are to be billed. None of them has a contract with PSO.

A few days later, the FSRU sailed to Qatar for a refill. While this may be allowed under the agreement, it was never part of original plan, which envisaged a permanently anchored FSRU being supplied with cargo vessels on a regular basis.

We have been told that Port Qasim did not dredge the channel deep enough for the kind of large ships that Qatargas wants to use for transporting LNG.

But perhaps the biggest loophole has been the complete absence of thought on exactly where the imported gas will be used in the long run. All along, petroleum ministry officials had insisted that imported gas would replace diesel and furnace oil, which is used to run half a dozen power plants.

That made economic sense. It would allow saving foreign exchange since LNG continues to remain cheaper that diesel and private power producers have the financial muscle to set aside cash for LNG imports. As it has turned out, that was easier said than done.

“Government officials haven’t done their homework. They come to table every time with unworkable suggestions,” a CEO of one of the power companies involved in this negotiation said. “They want us to make payments against LNG purchases every 14 days without realizing that it takes months for WAPDA to clear our dues.”

The government has also floated the idea of building an 1,100km long pipeline at a cost of $2 billion for transporting imported gas upcountry.

Fasih Ahmed, a director of Pakistan Gasport Limited, which has bid for a second FSRU-based terminal, says the national gas grid does not have enough capacity to absorb volumes from planned LNG and Iran-Pakistan pipeline projects.

“Despite a near unanimous consensus on LNG for fuel substitution and power-sector efficiencies, it took Pakistan nine years to achieve natural-gas imports. The governmental and regulatory apparatus should have been developed during this time to gear up for handling, distributing and regulating imported gas.”

The second FSRU terminal will also be located at Port Qasim. But hopefully lessons would have been learned by the time it is awarded.

Almost all the officials I spoke to appreciate the effort Petroleum Minister Abbasi has put into the LNG project. “It takes a lot of courage to take on people in your own government,” said an official referring to Abbasi’s recent press conference in which he blasted ministries of finance and water and power. “But people will doubt even good intentions because of incompetence of the government machinery.”

In that backdrop, the month of March was a watershed. It marked the beginning of gas imports into Pakistan. But instead of being a moment to cheer about, it has become another example of bad execution, poor governance and myopic policy.

The idea to import gas is not new. Successive governments have mulled over it for at least 10 years. Yet, what has happened with the first liquefied natural gas (LNG) import terminal is a reflection of how the energy issue has been handled in past.

For more than 57 years, the country has drilled holes in ground to suck out this hydrocarbon, exploiting an area stretching from the barren land of Balochistan’s Dera Bugti to the Gambat South Block in Sindh, and all the way up to Tal in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

As a result, a zigzagging web of pipelines was laid across the country – put together that’s more than 165,000 kilometers. Gas was everywhere and for everyone.

Long considered to be an abundant indigenous resource unlike oil, which was imported, its price was kept below international level for so many years that households and commercial users started to take it for granted. The result of this exploitation has been that among all the sources of energy fueling the country, natural gas has a share of 50 percent.

Effort was made to spur domestic gas output through new policies, which offered better return to petroleum exploration and production companies. But production has remained stagnant at 4,000 million cubic feet per day (MMCFD). Demand, on the other hand, has soared beyond 6,000 MMCFD.

Gas shortage has also compounded the electricity crisis. Back in the 1990s when the private sector was encouraged to invest in building thermal power plants, most of them were based on furnace oil because its price at Rs12,000 per ton was not a big deal.

But the folly of this decision became obvious within a few years after the oil price skyrocketed. As a result, power generation on gas was encouraged and the power sector gradually became one of largest gas consumers.

In 2010, gas accounted for 55 percent of thermal electricity being generated, while the remaining plants used furnace oil and diesel. By 2014 the ratio had reversed to 39 percent, because more and more of gas was being diverted to domestic consumers because of the shortage.

An attempt to counter this situation by importing gas import had begun in earnest in 2005. Everyone knew that importing gas via a pipeline from Iran was not possible because of Tehran’s confrontation with world powers.

Lengthy studies and negotiations on the Mashal LNG Project went on for several years. When the project was finally awarded, the apex court struck it down on charges of bad governance. Work on other LNG terminals also started. However none made it beyond the drawing board.

A zigzagging web of pipelines was laid across the country

Then in 2014, Engro Corporation won the bid to build an LNG terminal. The project involved a large ship known as FSRU (floating storage and regasification unit), which has onboard storage tanks and a processing plant to convert super-chilled liquid methane back into gaseous form.

Sheikh Imran ul Haque, who looks after Engro’s chemical business, was tasked to ensure that the terminal becomes operational on time. He and his team were able to develop physical infrastructure which involved a jetty and pipeline and complete complex and lengthy negotiations within a record 11 months. But even before the FSRU anchored at Port Qasim, problems had started to emerge.

Engro, as operator of the terminal, is responsible for receiving LNG shipments and pass them on to the national pipeline grid. For this service, it is entitled to receive $272,000 per day as a capacity charge even if not a single molecule of gas goes through its system.

The government has taken upon itself to arrange and import gas. Considering the costs associated with leaving the terminal unused, policymakers should have arranged regular import shipments. However, the so-called government-to-government deal with Qatar hasn’t worked the way it was supposed to. The FSRU that anchored in last week of March brought along 3,000 MMCF of gas. That was a stopgap arrangement to save face. Petroleum Minister Shahid Khaqan Abbasi was quick to suggest that the cargo was imported and paid for by the private sector.

“The first consignment was booked by Pakistan State Oil (PSO). Qataris would only deal with PSO, which had to open a Rs3.2 billion letter of credit in their favor,” said an industry official who used to oversee energy supply chain.

This should have been a straightforward affair: imported gas comes into the system, increasing the available supply, which is distributed at a decided price among industrial consumers desperately in need. But that’s not the case.

When officials say that LNG will be used to run power plants located in Punjab, it doesn’t mean that gas will be delivered in some dedicated pipeline all the way from the port in Karachi. As a matter of fact, imported gas is being distributed among bulk consumers scattered near Port Qasim’s vicinity. This is specifically being done to avoid wastage which occurs due to pipeline leakages and theft.

But somehow, the price difference has to be made up for. After all, the price of imported gas at $12.5 per unit is much more than the existing average consumer price of just $4. And this is where the complex regulatory structure comes into play and makes things worse.

Consumer gas price is determined by the Oil and Gas Regulatory Authority (Ogra). Private parties who will ultimately have to pay for the first LNG consignment are fertilizer producers, which buy gas from the two utilities –SSGC and SNGPL – at a subsidized price. The issue is not the higher price they have to pay, but how they are to be billed. None of them has a contract with PSO.

A few days later, the FSRU sailed to Qatar for a refill. While this may be allowed under the agreement, it was never part of original plan, which envisaged a permanently anchored FSRU being supplied with cargo vessels on a regular basis.

"Government officials haven't done their homework"

We have been told that Port Qasim did not dredge the channel deep enough for the kind of large ships that Qatargas wants to use for transporting LNG.

But perhaps the biggest loophole has been the complete absence of thought on exactly where the imported gas will be used in the long run. All along, petroleum ministry officials had insisted that imported gas would replace diesel and furnace oil, which is used to run half a dozen power plants.

That made economic sense. It would allow saving foreign exchange since LNG continues to remain cheaper that diesel and private power producers have the financial muscle to set aside cash for LNG imports. As it has turned out, that was easier said than done.

“Government officials haven’t done their homework. They come to table every time with unworkable suggestions,” a CEO of one of the power companies involved in this negotiation said. “They want us to make payments against LNG purchases every 14 days without realizing that it takes months for WAPDA to clear our dues.”

The government has also floated the idea of building an 1,100km long pipeline at a cost of $2 billion for transporting imported gas upcountry.

Fasih Ahmed, a director of Pakistan Gasport Limited, which has bid for a second FSRU-based terminal, says the national gas grid does not have enough capacity to absorb volumes from planned LNG and Iran-Pakistan pipeline projects.

“Despite a near unanimous consensus on LNG for fuel substitution and power-sector efficiencies, it took Pakistan nine years to achieve natural-gas imports. The governmental and regulatory apparatus should have been developed during this time to gear up for handling, distributing and regulating imported gas.”

The second FSRU terminal will also be located at Port Qasim. But hopefully lessons would have been learned by the time it is awarded.

Almost all the officials I spoke to appreciate the effort Petroleum Minister Abbasi has put into the LNG project. “It takes a lot of courage to take on people in your own government,” said an official referring to Abbasi’s recent press conference in which he blasted ministries of finance and water and power. “But people will doubt even good intentions because of incompetence of the government machinery.”