A Baloch woman wearing her bridal jewelry could walk alone from one end of the Balochistan province to the other in the old days. Baloch elders liked using this example to explain to me the difference between the old days and the present ones. People had honour then, they say, and no one would dare molest or steal from the woman in question.

That time has gone. Law and order is now a major problem – and the elders blamed the deterioration in the administration mainly on outside influences in society.

The Case Study

Let me present a case study and, after making allowances for the different cultural and historical context, see what lessons can be learned for Pakistan today. My case study is based on Balochistan, which is perhaps one of the most important but underrated provinces of Pakistan. In area it comprises almost half of Pakistan’s total. There is also unrest in the province, and the central government too frequently uses security personnel to solve political and law and order problems. Horror stories of brutal repression circulate. There are also rumors of foreign powers fishing in the troubled waters of Balochistan. To make matters worse, Balochistan which should be treated with special attention, is often dismissed by the military and political elites of Pakistan as backward, illiterate and unsophisticated.

In June 1986, when I had recently taken over the Sibi division as commissioner, Mir Noor Muhammad Jamali, a chieftain of the influential Jamali tribe, was kidnapped from Nasirabad, a district headquarters in Sibi division. The miscreants were a notorious gang of dacoits, an armed criminal gang. The dacoits headed out for their base in the Sindh province with their prize. This incident came after a series of kidnappings in which dacoits would cross over from Sindh to kidnap people and take them across the provincial border for ransom. The operations were widespread and becoming increasingly bold. For the dacoits, it was a highly successful criminal and economic enterprise.

But as the main road into Balochistan from Pakistan passed through my division, these exploits were making passengers and travelers very nervous. I waited for a dramatic moment to tackle the problem decisively and felt this could be it.

The kidnapping incident became a test-case for my reputation. I took it as a personal challenge and risked all in the actions that I took. Immediately mobilising all my resources, I followed the gang in “hot pursuit.” I instructed one group of my officers to form an advance scouts’ party, along with members of the Jamali tribe, and to leave without a moment’s delay so as not to lose the trail of the gang. As the second prong of my attack, I gathered whatever armed men I had, including my magnificent Bugti bodyguard which struck terror in the hearts of those who saw them with their fierce looks and adornment of deadly looking knives and guns, and crossed into the Sindh province. I had a great team of field officers, especially the excellent head of the police Sikander Muhammadzai, who unhesitatingly led his force personally over the next few days. People had noticed the close cooperation between the commissioner and the Deputy Inspector-General, and that added to the confidence in the administration.

As commissioner of Sibi division, I was not authorised to act outside my jurisdiction, and crossing into another province with a raiding party was unprecedented and full of potential dangers. The situation was fraught with danger and the chances of failure high. I was constantly in touch, however, with the chief minister, the head of Balochistan province, who had telephoned his counterpart in Sindh, informing him of my imminent arrival in his area, and this gave me administrative cover. The chief minister’s full support made all the difference.

I knew if the trail went cold, we would not be able to recover Noor Jamali easily – if at all. We were relentless in our chase, however. Gunfire was regularly exchanged, and several people wounded, but we kept after the dacoits. We were shooting at each other and at several points were just a few hundred yards away. This exchange of fire continued into the night. There was every chance of being hit not only by the dacoits but our own men who seemed to be shooting in every direction. The heat was oppressive, and the region desolate. We had virtually no food or water for three days. When I could, I snatched sleep at night in the back seat of the commissioner’s large SUV, with my Bugti bodyguard throwing a ring of protection around it. My protection became a matter of honour for them. With their fierce-looking appearance and reputation, their presence added to the earnestness of our purpose.

This was Wild West stuff.

As the news spread, anger grew among the Baloch tribes at the outrage. A tribal war erupting across provincial borders was a real danger. In the meantime, on the national level, the opposition was hammering at the newly formed elected government in Islamabad about losing control of the law-and-order situation in the country. The kidnap case was being used at the national level to score points. It was widely discussed in the media.

Deep in the Sindh province, we were in the middle of what I described in my official report later as “no man’s land.” The people in these villages found it hard to believe that an officer of the seniority of the commissioner was among them. The police at night usually locked themselves behind closed doors in their dilapidated police stations in fear of the dacoits. “The Sind Government,” I wrote in my report, “cannot even collect revenue from here,” and “the local police were demoralised and fearful.”

I was in touch with the ring leaders through intermediaries and made it clear I would not return to Balochistan without my tribal chief. And I would not pay a single rupee as ransom money. To surrender would have meant opening the gates for other dacoits to operate in my area. After the intensity of our pursuit, the dacoits felt it was no longer worth keeping Noor Jamali. They told him what was happening was unprecedented and would ruin their business. They could not have senior officers exchanging fire with them and tramping around in their areas, thus exposing their hideouts. They released Noor Jamali unconditionally. Ironically, they gave him some rupees for bus fare and left him near a track where a local bus could be found and would take him to where we were waiting. He was brought home safely. Given the national prominence the matter had assumed, it was widely reported in the press. The prime minister and chief minister gave statements to show the extent of control they had over law and order in the country.

Expressing his appreciation, the chief minister of Balochistan sent me an official letter in which he wrote: “This is to place on record the appreciation of the Provincial Government for good work done and the high sense of duty displayed by you in giving a hot pursuit to the criminals who had abducted a notable of Jamali tribe namely Mir Noor Muhammad Jamali and taken to Sind area. But for the untiring efforts and constant pressure put on the criminals’ recovery of the abducted tribal elder would not have been possible. It is only with such dedication and hard work that these undesirable elements can be controlled and discouraged. I am confident that you would keep up and continue with dedication for the eradication of such elements.”

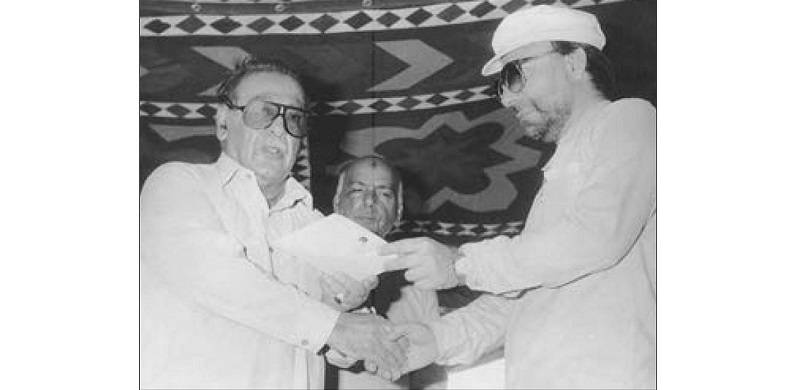

A Baloch chief himself and the former ruler of a Baloch state, Mir Jam Qadir Khan was a scholarly, compassionate man with a desire to serve his people. He always treated me with honour and made me feel welcome in Balochistan. He followed up his generous letter with an equally generous gesture. He convened an All-Balochistan jirga or council of chiefs and members of Parliament, where in glowing terms he publicly honoured my key officials and I with special awards.

The word had got out to dacoits in the region: any breach of law would be met by swift and resolute action. I was informed by my police that a saying was circulating among the dacoits that it was best to lie low and not break the law as the “new commissioner was quite mad” and capable of turning up with a large force at their doorstep in the middle of the night if they violated the law. I would not have any law-and-order problem for the rest of my tenure as commissioner of Sibi Division.

The complicated kidnapping case would not have been resolved if the commissioner was not fully involved at the centre of the operation, directing and coordinating it, or without the full backing he received from the chief minister, the cooperation from his service colleagues and the moral support of the public. If there is coordination and cooperation, no problem in the field is too great to resolve.

Analysis

Reading the literature I came across an old proverb about the Baloch. It said “honour the Baloch.” I learned to appreciate the saying and discovered that it was quite true. It was an old proverb from the British days and based on the assessment of experienced political officers on how best to deal with the tribes in what is now Pakistan. Of course, it reeked of colonial and racial prejudice: One group, it said, should be treated with toughness and they will submit, another group could be bribed easily but the Baloch, the proverb said, had to be treated with honour. Well, I found this part of the proverb quite true. The Baloch did not respond to threats or other pressures, but they will do anything for you if you honoured them. The simple principle was often missed by outside officers and often landed them in unnecessary trouble. Rather than creating bridges with the local people, they ended up creating problems.

I believe a stable district with a contented population ensures a stable and secure nation. The reverse is also true: chaos at the district level will almost certainly destabilise the nation. As a firm believer in this theory, I am dismayed at the state of affairs at the district level in Pakistan today. The emphasis seems to be on economic and finance planning—but please remember if there is chaos at the district level few will want to invest, teachers and students would avoid school and politicians would spend their time attacking and blaming each other. Today the politicians have put the cart before the horse.

I hear horror stories of officers – including senior-most ones like the chief secretary and the Inspector-General of the police of the province – being changed with alarming frequency. That will not do; it is guaranteed to bring the administration to a standstill. The ‘good guys’ will be in despair and the ‘bad guys’ jubilant as they will have a free hand. The administration must be seen to be impartial and active and impeccable in their integrity. Many of the cases identified with success in the field in my case were a result of my acting with confidence and the assumption that behind me stood the government of Pakistan. Of course, it was bluff, but it worked. If, instead, the senior administration was constantly pulling my leg, I would have found it difficult if not impossible to work in the field. That is the situation today.

Running a subdivision or a district is not the job of the chief secretary or the IG police but that of the district officer in charge of that area. Too many “experts” are flying in from the US, clueless about rural conditions, and forcing their advice on officials in the field. As a result, officials are now so disheartened that they may be in no condition to meet the challenge of district life in these chaotic times.

The government is facing the age-old problem of dealing with the breakdown of law-and-order. There are several factors to consider: There is the coordination between the provincial government and the divisional/district administration, between the civil administration and the police, between the elected representatives and the administration and the local elders.

And if all fails there is always the military as aid to civil authority.

In my long career in the field, I avoided calling in the army. They were always obliging and cooperative, but I felt if I called in the army, then I - as the civil officer - had failed. I felt that if the different parts of the system work swiftly in coordination and with resolve, there is no problem that cannot be solved.

There are lessons for us today. Given the low morale, neither civil nor police officials would be inclined to risk their lives in facing an exchange of gunfire. Before long we would have seen large numbers of heavily armed security personnel in armoured vehicles – likely with little understanding of local culture – moving into the area. Anyone who appeared slightly suspicious – which could include virtually every citizen – would be picked up and taken for “interrogation.” Ordinary people would be outraged by the disproportionate use of force. The dacoits who thrive on local sympathy would have simply let things die down before returning to business as usual.

Conclusion

So let us sum up: select the right man for the right job. There are some excellent officers if government looks for them. But do not, I repeat, do not appoint the minister’s nephew or member of the clan or someone who has bribed the minister doing the posting. Once the right man is in the field, give him full backing and leave him alone in the post. You cannot have the sword of uncertainty hanging over his head. It paralyzes him for any decision making and creates anxiety. Every step he takes has the potential to land him in trouble. So, he plays it safe and does not take any steps.

In my experience, I was constantly taking risks. But my intentions were to solve a problem on the ground, and I was not thinking to watch what could happen to me. In the process and in the field, I faced really large mobs of angry young men. I have been shot at several times in the tribal areas where there was no law and order. And I have been threatened by senior political figures to stuff the ballot boxes or face dire consequences. In one situation, a federal minister in the tribal areas asked me to use my influence to manipulate and ensure his victory. When I refused, he asked me to be in my office early next morning as prime minister Z.A. Bhutto would ring me directly and admonish me for not helping his minister get votes with my influence. I went home and told my wife to pack. I went early next morning to the office; no call came. The minister lost the elections and later, meeting my father, praised me saying I was the best political officer he had met, but I didn’t help him in the elections.

As for outside officers serving in Balochistan, especially with the current conditions, let me point out that I was an outsider serving under a Baloch chief minister and I never ever had problems. On the contrary, the chief minister would urge his members of parliament and officials that I deserved full support because of my integrity and efficiency. I never felt an outsider and in turn I had the confidence to take risks in achieving and resolving problems on the ground. The big lesson again: administration is always a tricky business, but with sincerity and goodwill any problem can be overcome.

In conclusion, you can see that even a difficult situation in a difficult area can be successfully negotiated with the right personnel in charge. That is why it is crucial to strengthen what the Quaid-i-Azam called “the steel frame” of Pakistan, that is the civil service of Pakistan holding up the structure of the state. Today, with too frequent transfers and the whims of some political master or the other, constant attacks in the media about an inefficient and incompetent bureaucracy, the low pay and the tattered prestige of the service, it is surprising why talented young Pakistanis would want to join the once prestigious civil service. It is precisely this trend towards the inevitable collapse of the service that needs to be reversed.

As for the civil services, they must not forget they are literally the ‘servants’ of the public, not the other way round. They must do some soul-searching and ask as to why they have acquired such a negative reputation as an arrogant and incompetent lot.

But let us also look at the other side of the coin. Civil servants or bureaucrats are constantly chastised in the media, humiliated and sacked – resulting in low morale and little incentive to take risks for their profession. While they deserve criticism if they are arrogant, corrupt and inept, they must also be recognised when they perform well. A ‘shabbash,’ especially public recognition, is part of maintaining good civil service morale. The chief minister’s very public and generous acknowledgment in the Balochistan case study – as I have shared above – did much to boost the morale of the local administration.

That time has gone. Law and order is now a major problem – and the elders blamed the deterioration in the administration mainly on outside influences in society.

The Case Study

Let me present a case study and, after making allowances for the different cultural and historical context, see what lessons can be learned for Pakistan today. My case study is based on Balochistan, which is perhaps one of the most important but underrated provinces of Pakistan. In area it comprises almost half of Pakistan’s total. There is also unrest in the province, and the central government too frequently uses security personnel to solve political and law and order problems. Horror stories of brutal repression circulate. There are also rumors of foreign powers fishing in the troubled waters of Balochistan. To make matters worse, Balochistan which should be treated with special attention, is often dismissed by the military and political elites of Pakistan as backward, illiterate and unsophisticated.

In June 1986, when I had recently taken over the Sibi division as commissioner, Mir Noor Muhammad Jamali, a chieftain of the influential Jamali tribe, was kidnapped from Nasirabad, a district headquarters in Sibi division. The miscreants were a notorious gang of dacoits, an armed criminal gang. The dacoits headed out for their base in the Sindh province with their prize. This incident came after a series of kidnappings in which dacoits would cross over from Sindh to kidnap people and take them across the provincial border for ransom. The operations were widespread and becoming increasingly bold. For the dacoits, it was a highly successful criminal and economic enterprise.

But as the main road into Balochistan from Pakistan passed through my division, these exploits were making passengers and travelers very nervous. I waited for a dramatic moment to tackle the problem decisively and felt this could be it.

The kidnapping incident became a test-case for my reputation. I took it as a personal challenge and risked all in the actions that I took. Immediately mobilising all my resources, I followed the gang in “hot pursuit.” I instructed one group of my officers to form an advance scouts’ party, along with members of the Jamali tribe, and to leave without a moment’s delay so as not to lose the trail of the gang. As the second prong of my attack, I gathered whatever armed men I had, including my magnificent Bugti bodyguard which struck terror in the hearts of those who saw them with their fierce looks and adornment of deadly looking knives and guns, and crossed into the Sindh province. I had a great team of field officers, especially the excellent head of the police Sikander Muhammadzai, who unhesitatingly led his force personally over the next few days. People had noticed the close cooperation between the commissioner and the Deputy Inspector-General, and that added to the confidence in the administration.

As commissioner of Sibi division, I was not authorised to act outside my jurisdiction, and crossing into another province with a raiding party was unprecedented and full of potential dangers. The situation was fraught with danger and the chances of failure high. I was constantly in touch, however, with the chief minister, the head of Balochistan province, who had telephoned his counterpart in Sindh, informing him of my imminent arrival in his area, and this gave me administrative cover. The chief minister’s full support made all the difference.

I knew if the trail went cold, we would not be able to recover Noor Jamali easily – if at all. We were relentless in our chase, however. Gunfire was regularly exchanged, and several people wounded, but we kept after the dacoits. We were shooting at each other and at several points were just a few hundred yards away. This exchange of fire continued into the night. There was every chance of being hit not only by the dacoits but our own men who seemed to be shooting in every direction. The heat was oppressive, and the region desolate. We had virtually no food or water for three days. When I could, I snatched sleep at night in the back seat of the commissioner’s large SUV, with my Bugti bodyguard throwing a ring of protection around it. My protection became a matter of honour for them. With their fierce-looking appearance and reputation, their presence added to the earnestness of our purpose.

This was Wild West stuff.

As the news spread, anger grew among the Baloch tribes at the outrage. A tribal war erupting across provincial borders was a real danger. In the meantime, on the national level, the opposition was hammering at the newly formed elected government in Islamabad about losing control of the law-and-order situation in the country. The kidnap case was being used at the national level to score points. It was widely discussed in the media.

Deep in the Sindh province, we were in the middle of what I described in my official report later as “no man’s land.” The people in these villages found it hard to believe that an officer of the seniority of the commissioner was among them. The police at night usually locked themselves behind closed doors in their dilapidated police stations in fear of the dacoits. “The Sind Government,” I wrote in my report, “cannot even collect revenue from here,” and “the local police were demoralised and fearful.”

In my long career in the field, I avoided calling in the army. They were always obliging and cooperative, but I felt if I called in the army, then I - as the civil officer - had failed

I was in touch with the ring leaders through intermediaries and made it clear I would not return to Balochistan without my tribal chief. And I would not pay a single rupee as ransom money. To surrender would have meant opening the gates for other dacoits to operate in my area. After the intensity of our pursuit, the dacoits felt it was no longer worth keeping Noor Jamali. They told him what was happening was unprecedented and would ruin their business. They could not have senior officers exchanging fire with them and tramping around in their areas, thus exposing their hideouts. They released Noor Jamali unconditionally. Ironically, they gave him some rupees for bus fare and left him near a track where a local bus could be found and would take him to where we were waiting. He was brought home safely. Given the national prominence the matter had assumed, it was widely reported in the press. The prime minister and chief minister gave statements to show the extent of control they had over law and order in the country.

Expressing his appreciation, the chief minister of Balochistan sent me an official letter in which he wrote: “This is to place on record the appreciation of the Provincial Government for good work done and the high sense of duty displayed by you in giving a hot pursuit to the criminals who had abducted a notable of Jamali tribe namely Mir Noor Muhammad Jamali and taken to Sind area. But for the untiring efforts and constant pressure put on the criminals’ recovery of the abducted tribal elder would not have been possible. It is only with such dedication and hard work that these undesirable elements can be controlled and discouraged. I am confident that you would keep up and continue with dedication for the eradication of such elements.”

A Baloch chief himself and the former ruler of a Baloch state, Mir Jam Qadir Khan was a scholarly, compassionate man with a desire to serve his people. He always treated me with honour and made me feel welcome in Balochistan. He followed up his generous letter with an equally generous gesture. He convened an All-Balochistan jirga or council of chiefs and members of Parliament, where in glowing terms he publicly honoured my key officials and I with special awards.

The word had got out to dacoits in the region: any breach of law would be met by swift and resolute action. I was informed by my police that a saying was circulating among the dacoits that it was best to lie low and not break the law as the “new commissioner was quite mad” and capable of turning up with a large force at their doorstep in the middle of the night if they violated the law. I would not have any law-and-order problem for the rest of my tenure as commissioner of Sibi Division.

The complicated kidnapping case would not have been resolved if the commissioner was not fully involved at the centre of the operation, directing and coordinating it, or without the full backing he received from the chief minister, the cooperation from his service colleagues and the moral support of the public. If there is coordination and cooperation, no problem in the field is too great to resolve.

There are lessons for us today. Given the low morale, neither civil nor police officials would be inclined to risk their lives in facing an exchange of gunfire. Before long we would have seen large numbers of heavily armed security personnel in armoured vehicles – likely with little understanding of local culture – moving into the area. Anyone who appeared slightly suspicious – which could include virtually every citizen – would be picked up and taken for “interrogation”

Analysis

Reading the literature I came across an old proverb about the Baloch. It said “honour the Baloch.” I learned to appreciate the saying and discovered that it was quite true. It was an old proverb from the British days and based on the assessment of experienced political officers on how best to deal with the tribes in what is now Pakistan. Of course, it reeked of colonial and racial prejudice: One group, it said, should be treated with toughness and they will submit, another group could be bribed easily but the Baloch, the proverb said, had to be treated with honour. Well, I found this part of the proverb quite true. The Baloch did not respond to threats or other pressures, but they will do anything for you if you honoured them. The simple principle was often missed by outside officers and often landed them in unnecessary trouble. Rather than creating bridges with the local people, they ended up creating problems.

I believe a stable district with a contented population ensures a stable and secure nation. The reverse is also true: chaos at the district level will almost certainly destabilise the nation. As a firm believer in this theory, I am dismayed at the state of affairs at the district level in Pakistan today. The emphasis seems to be on economic and finance planning—but please remember if there is chaos at the district level few will want to invest, teachers and students would avoid school and politicians would spend their time attacking and blaming each other. Today the politicians have put the cart before the horse.

I hear horror stories of officers – including senior-most ones like the chief secretary and the Inspector-General of the police of the province – being changed with alarming frequency. That will not do; it is guaranteed to bring the administration to a standstill. The ‘good guys’ will be in despair and the ‘bad guys’ jubilant as they will have a free hand. The administration must be seen to be impartial and active and impeccable in their integrity. Many of the cases identified with success in the field in my case were a result of my acting with confidence and the assumption that behind me stood the government of Pakistan. Of course, it was bluff, but it worked. If, instead, the senior administration was constantly pulling my leg, I would have found it difficult if not impossible to work in the field. That is the situation today.

Running a subdivision or a district is not the job of the chief secretary or the IG police but that of the district officer in charge of that area. Too many “experts” are flying in from the US, clueless about rural conditions, and forcing their advice on officials in the field. As a result, officials are now so disheartened that they may be in no condition to meet the challenge of district life in these chaotic times.

The government is facing the age-old problem of dealing with the breakdown of law-and-order. There are several factors to consider: There is the coordination between the provincial government and the divisional/district administration, between the civil administration and the police, between the elected representatives and the administration and the local elders.

And if all fails there is always the military as aid to civil authority.

In my long career in the field, I avoided calling in the army. They were always obliging and cooperative, but I felt if I called in the army, then I - as the civil officer - had failed. I felt that if the different parts of the system work swiftly in coordination and with resolve, there is no problem that cannot be solved.

There are lessons for us today. Given the low morale, neither civil nor police officials would be inclined to risk their lives in facing an exchange of gunfire. Before long we would have seen large numbers of heavily armed security personnel in armoured vehicles – likely with little understanding of local culture – moving into the area. Anyone who appeared slightly suspicious – which could include virtually every citizen – would be picked up and taken for “interrogation.” Ordinary people would be outraged by the disproportionate use of force. The dacoits who thrive on local sympathy would have simply let things die down before returning to business as usual.

Conclusion

So let us sum up: select the right man for the right job. There are some excellent officers if government looks for them. But do not, I repeat, do not appoint the minister’s nephew or member of the clan or someone who has bribed the minister doing the posting. Once the right man is in the field, give him full backing and leave him alone in the post. You cannot have the sword of uncertainty hanging over his head. It paralyzes him for any decision making and creates anxiety. Every step he takes has the potential to land him in trouble. So, he plays it safe and does not take any steps.

In my experience, I was constantly taking risks. But my intentions were to solve a problem on the ground, and I was not thinking to watch what could happen to me. In the process and in the field, I faced really large mobs of angry young men. I have been shot at several times in the tribal areas where there was no law and order. And I have been threatened by senior political figures to stuff the ballot boxes or face dire consequences. In one situation, a federal minister in the tribal areas asked me to use my influence to manipulate and ensure his victory. When I refused, he asked me to be in my office early next morning as prime minister Z.A. Bhutto would ring me directly and admonish me for not helping his minister get votes with my influence. I went home and told my wife to pack. I went early next morning to the office; no call came. The minister lost the elections and later, meeting my father, praised me saying I was the best political officer he had met, but I didn’t help him in the elections.

As for outside officers serving in Balochistan, especially with the current conditions, let me point out that I was an outsider serving under a Baloch chief minister and I never ever had problems. On the contrary, the chief minister would urge his members of parliament and officials that I deserved full support because of my integrity and efficiency. I never felt an outsider and in turn I had the confidence to take risks in achieving and resolving problems on the ground. The big lesson again: administration is always a tricky business, but with sincerity and goodwill any problem can be overcome.

In conclusion, you can see that even a difficult situation in a difficult area can be successfully negotiated with the right personnel in charge. That is why it is crucial to strengthen what the Quaid-i-Azam called “the steel frame” of Pakistan, that is the civil service of Pakistan holding up the structure of the state. Today, with too frequent transfers and the whims of some political master or the other, constant attacks in the media about an inefficient and incompetent bureaucracy, the low pay and the tattered prestige of the service, it is surprising why talented young Pakistanis would want to join the once prestigious civil service. It is precisely this trend towards the inevitable collapse of the service that needs to be reversed.

As for the civil services, they must not forget they are literally the ‘servants’ of the public, not the other way round. They must do some soul-searching and ask as to why they have acquired such a negative reputation as an arrogant and incompetent lot.

But let us also look at the other side of the coin. Civil servants or bureaucrats are constantly chastised in the media, humiliated and sacked – resulting in low morale and little incentive to take risks for their profession. While they deserve criticism if they are arrogant, corrupt and inept, they must also be recognised when they perform well. A ‘shabbash,’ especially public recognition, is part of maintaining good civil service morale. The chief minister’s very public and generous acknowledgment in the Balochistan case study – as I have shared above – did much to boost the morale of the local administration.