After about ten weeks of tense confrontation, on August 29, China and India agreed to pull back their forces from Doklam Plateau. The decision came a few days before the start of the ninth annual BRICS summit that was held in China’s Xiamen. Both sides, and especially China, scrambled to diplomatically end the military confrontation that was being called the worst in decades. But has the issue really been resolved or has it just been shelved only to recur?

Start of the conflict

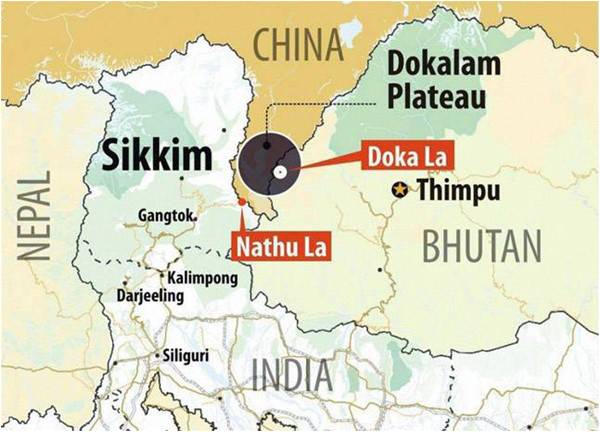

On June 16, in the remote Doklam Plateau near the China-Bhutan border, the Bhutanese authorities found that China had started constructing a road. The planned road fell several kilometers away from China-Bhutan. Although it is claimed by Bhutan, the area has been under China’s control from the very beginning. The disputed territory is far away from the tri-juncture of the Chinese, Indian and Bhutanese borders.

The current confrontation, it is emphasized, was between China and Bhutan; India had no direct link to it. However, shortly after Chinese construction workers were spotted, the Indian army swiftly entered from the Bhutanese sector into Chinese territory and physically stopped the men from going ahead.

In the past, it was common to see feuds erupt between China and India over their disputed borders. But it was rare to see the Indian military cross an international border, and that too on behalf of a third country. It was so provocative that the Chinese government and media blasted India in a reaction the likes of which had not been seen in decades. China refused to start a dialogue until India withdrew its forces from the area unconditionally. It is clear that politically, economically and militarily China has an upper hand over India but as time passed, China was seen to hurry to find a settlement.

Rationale of China’s diplomacy

It appears that there were three reasons behind China’s decision to seek a settlement. First, the ninth annual BRICS Summit (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) was due in less than a week. Had the Sino-Indian conflict dragged on, it was quite likely that Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi would have boycotted the summit. This could have proven to be a bigger setback for the Chinese leadership as well as for the future of BRICS. Why just in May, India had officially refused to attend the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Forum that was held in Beijing. Thus, to prevent India from absenting itself from BRICS, Beijing accepted a compromise which was not popular at the public level.

Second, in less than two months from BRICS, China will hold its 19th National Party Congress of the Communist Party of China, tentatively on October 18. The Congress will make major decisions, including the selection of the President, Prime Minister and seven core members of the Politburo Standing Committee (although both Xi Jinping and Li Keqiang are likely to be selected for another term).

The coming years are crucial for the Communist Party. In 2021, it will commemorate its 100th anniversary. Chinese leadership has set a number of goals to be achieved before this date. Parallel with this, President Xi has started the BRI, the largest project not only in the history of China but also in the history of the contemporary world. All these mega projects require a peaceful environment inside and around China. It is under these conditions that China compromised at Doklam.

The third reason does not appear to be obvious but did have some sway over China’s decision: the Tibet factor. Although India has endorsed China’s sovereignty over Tibet since Nehru’s time, in recent years, especially since the rightwing, hardline Modi government is in power, many Indian actions have contradicted the official stance. In April, just a month before BRI Forum, India invited the Dalai Lama to Tawang, a small town in the northeastern Indian-controlled state of Arunachal Pradesh/Southern Tibet. At that time, Pema Khandu, chief minister of Arunachal Pradesh/Southern Tibet, challenged Chinese sovereignty on Tibet. Although China reacted to these Indian moves, it did not allow the events to sabotage ties with India. China’s insistence on bringing Modi to attend the BRI Forum made clear the Chinese desire to keep up healthy relations with India. This policy is also reflected in China’s decision on the Doklam standoff.

India trumpets victory

New Delhi, on the other hand, has trumpeted the Doklam episode as its success. Indian media is full of stories praising what it called the Indian army’s courage to stand against “Chinese aggression”. A commentator in a leading English daily, said: “India is learning to behave like a superpower.” Throughout the period when tension was high, India received the backing of most of the Western media which is often critical of China’s policies on human rights issues, the South China Sea and democracy. In fact, both sides share the goal of China’s containment.

India’s justification for its incursion into Chinese-controlled territory under the obligation of the India-Bhutan Friendship Treaty of 2007 is flawed. A look at the treaty shows that there is no provision which demands military coordination in case of a crisis. Article 2 stipulates that given the close relationship, India and Bhutan “shall cooperate closely with each other on issues relating to their national interests.” While Article 4 allows Bhutan to import “whatever arms, ammunition, machinery, warlike material or stores as may be required or desired for the strength and welfare of Bhutan”, these clauses do not suggest a military alliance.

On the other hand, India’s rapid response to China’s construction of the road demonstrates that the Indian army was actually stationed in Bhutan. The Sino-Bhutan border is in name only; India treats it as an India-China border and has taken on its responsibility.

Bhutan is the only country in the region which lacks formal diplomatic relations with China. A part of the Sino-Bhutan border is also disputed between the two sides. Bhutan intends to establish formal diplomatic relations with China and is willing to settle the border dispute but India is the major hurdle in any settlement between China and Bhutan. The world is aware of Bhutan’s independent status in the comity of nations.

The Indian logic of intervention by crossing an international boundary has set a dangerous precedent in this nuclearized region. To mock Indian logic, a Chinese scholar flipped the argument to ask, should “the Pakistani government request a third country’s army [China] to enter into disputed territory between India and Pakistan, including India-controlled Kashmir?”

To reemphasize, China was constructing a road in a territory under its control when the Indian military intervened. If this exercise is emulated by other countries, it will surely lead to disasters. For example, Pakistan and India have disputed territory, namely Kashmir. If India begins construction in the parts of Kashmir under its administration, should Chinese forces on Pakistan’s behalf cross the Line of Control and stop it? Likewise, if India starts construction in Arunachal Pradesh/Southern Tibet, should Pakistani forces intervene to help China? The consequences of such a scenario are obvious to everyone.

There has been increased military jingoism in India under Modi. A few months earlier, it claimed that it had conducted “surgical strikes” in Pakistan. That means, according to the Indian statement, that the Indian military crossed the Line of Control, a de facto international border between India and Pakistan, conducted military operations inside Pakistan and returned to its bases. What if Pakistan responded? Although the “surgical strike” was a mere fantasy, given aggressive Indian designs and the craze for military weapons (according to SIPRI India is the world’s largest arms importer) such actions cannot be ruled out.

Furthermore, Indian action has emboldened the hawks and China bashers in the country. They drew the conclusion that India should harden its stance towards China. Some commentaries even suggested that India’s model should be emulated by other countries. “If others stand up, China will back down,” noted one analyst. The right-wing BJP will cash in on the Doklam issue in the next general elections.

The Chinese mantra may be that the world is big enough for China and India to develop simultaneously but the military standoff has made it clear that aside from diplomatic courtesies the hard reality of geopolitics present a very different picture. India considers China its main rival. One should not forget Vajpayee’s letter to the US president, terming China as the main threat and reason behind Indian nuclear tests in 1998. India has not emerged from that kind of thinking. To an extent, China’s rapid development has strengthened these Indian concerns.

Moreover, despite frantic diplomacy over the decades, both sides have not made any meaningful progress on their long-standing unmarked border. The disputed territory is almost five times the size of Taiwan. New Delhi is in no mood to withdraw an inch from what is under its control. Negotiations for a border settlement, to India, is akin to talking about what is under China’s control. In fact, instead of settling the traditional territorial dispute, over the years new challenges of a geopolitical nature have emerged between the two sides.

Thus, Indian action in Chinese territory which caused the Doklam standoff has far-reaching implications. It was an Indian attempt to solve the issue through military means which damaged the already weak Sino-Indian trust, threw cold water on BRICS and set a dangerous precedent of military intervention by violating international boundaries. The decision on August 29 to withdraw forces from the Doklam Plateau just shelved the conflict and did not solve it.

Dr Ghulam Ali teaches International Relations at the School of Marxism, Sichuan University of Science & Engineering, Zigong, China. The views expressed are his personal. He is the author of China-Pakistan Relations: A Historical Analysis (OUP 2017) ghulamali74@yahoo.com

Start of the conflict

On June 16, in the remote Doklam Plateau near the China-Bhutan border, the Bhutanese authorities found that China had started constructing a road. The planned road fell several kilometers away from China-Bhutan. Although it is claimed by Bhutan, the area has been under China’s control from the very beginning. The disputed territory is far away from the tri-juncture of the Chinese, Indian and Bhutanese borders.

The current confrontation, it is emphasized, was between China and Bhutan; India had no direct link to it. However, shortly after Chinese construction workers were spotted, the Indian army swiftly entered from the Bhutanese sector into Chinese territory and physically stopped the men from going ahead.

In the past, it was common to see feuds erupt between China and India over their disputed borders. But it was rare to see the Indian military cross an international border, and that too on behalf of a third country. It was so provocative that the Chinese government and media blasted India in a reaction the likes of which had not been seen in decades. China refused to start a dialogue until India withdrew its forces from the area unconditionally. It is clear that politically, economically and militarily China has an upper hand over India but as time passed, China was seen to hurry to find a settlement.

In the past, it was common to see feuds erupt between China and India over their disputed borders. But it was rare to see the Indian military cross an international border, and that too on behalf of a third country

Rationale of China’s diplomacy

It appears that there were three reasons behind China’s decision to seek a settlement. First, the ninth annual BRICS Summit (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) was due in less than a week. Had the Sino-Indian conflict dragged on, it was quite likely that Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi would have boycotted the summit. This could have proven to be a bigger setback for the Chinese leadership as well as for the future of BRICS. Why just in May, India had officially refused to attend the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Forum that was held in Beijing. Thus, to prevent India from absenting itself from BRICS, Beijing accepted a compromise which was not popular at the public level.

Second, in less than two months from BRICS, China will hold its 19th National Party Congress of the Communist Party of China, tentatively on October 18. The Congress will make major decisions, including the selection of the President, Prime Minister and seven core members of the Politburo Standing Committee (although both Xi Jinping and Li Keqiang are likely to be selected for another term).

The coming years are crucial for the Communist Party. In 2021, it will commemorate its 100th anniversary. Chinese leadership has set a number of goals to be achieved before this date. Parallel with this, President Xi has started the BRI, the largest project not only in the history of China but also in the history of the contemporary world. All these mega projects require a peaceful environment inside and around China. It is under these conditions that China compromised at Doklam.

The third reason does not appear to be obvious but did have some sway over China’s decision: the Tibet factor. Although India has endorsed China’s sovereignty over Tibet since Nehru’s time, in recent years, especially since the rightwing, hardline Modi government is in power, many Indian actions have contradicted the official stance. In April, just a month before BRI Forum, India invited the Dalai Lama to Tawang, a small town in the northeastern Indian-controlled state of Arunachal Pradesh/Southern Tibet. At that time, Pema Khandu, chief minister of Arunachal Pradesh/Southern Tibet, challenged Chinese sovereignty on Tibet. Although China reacted to these Indian moves, it did not allow the events to sabotage ties with India. China’s insistence on bringing Modi to attend the BRI Forum made clear the Chinese desire to keep up healthy relations with India. This policy is also reflected in China’s decision on the Doklam standoff.

India trumpets victory

New Delhi, on the other hand, has trumpeted the Doklam episode as its success. Indian media is full of stories praising what it called the Indian army’s courage to stand against “Chinese aggression”. A commentator in a leading English daily, said: “India is learning to behave like a superpower.” Throughout the period when tension was high, India received the backing of most of the Western media which is often critical of China’s policies on human rights issues, the South China Sea and democracy. In fact, both sides share the goal of China’s containment.

India’s justification for its incursion into Chinese-controlled territory under the obligation of the India-Bhutan Friendship Treaty of 2007 is flawed. A look at the treaty shows that there is no provision which demands military coordination in case of a crisis. Article 2 stipulates that given the close relationship, India and Bhutan “shall cooperate closely with each other on issues relating to their national interests.” While Article 4 allows Bhutan to import “whatever arms, ammunition, machinery, warlike material or stores as may be required or desired for the strength and welfare of Bhutan”, these clauses do not suggest a military alliance.

On the other hand, India’s rapid response to China’s construction of the road demonstrates that the Indian army was actually stationed in Bhutan. The Sino-Bhutan border is in name only; India treats it as an India-China border and has taken on its responsibility.

Bhutan is the only country in the region which lacks formal diplomatic relations with China. A part of the Sino-Bhutan border is also disputed between the two sides. Bhutan intends to establish formal diplomatic relations with China and is willing to settle the border dispute but India is the major hurdle in any settlement between China and Bhutan. The world is aware of Bhutan’s independent status in the comity of nations.

The Indian logic of intervention by crossing an international boundary has set a dangerous precedent in this nuclearized region. To mock Indian logic, a Chinese scholar flipped the argument to ask, should “the Pakistani government request a third country’s army [China] to enter into disputed territory between India and Pakistan, including India-controlled Kashmir?”

To reemphasize, China was constructing a road in a territory under its control when the Indian military intervened. If this exercise is emulated by other countries, it will surely lead to disasters. For example, Pakistan and India have disputed territory, namely Kashmir. If India begins construction in the parts of Kashmir under its administration, should Chinese forces on Pakistan’s behalf cross the Line of Control and stop it? Likewise, if India starts construction in Arunachal Pradesh/Southern Tibet, should Pakistani forces intervene to help China? The consequences of such a scenario are obvious to everyone.

There has been increased military jingoism in India under Modi. A few months earlier, it claimed that it had conducted “surgical strikes” in Pakistan. That means, according to the Indian statement, that the Indian military crossed the Line of Control, a de facto international border between India and Pakistan, conducted military operations inside Pakistan and returned to its bases. What if Pakistan responded? Although the “surgical strike” was a mere fantasy, given aggressive Indian designs and the craze for military weapons (according to SIPRI India is the world’s largest arms importer) such actions cannot be ruled out.

Furthermore, Indian action has emboldened the hawks and China bashers in the country. They drew the conclusion that India should harden its stance towards China. Some commentaries even suggested that India’s model should be emulated by other countries. “If others stand up, China will back down,” noted one analyst. The right-wing BJP will cash in on the Doklam issue in the next general elections.

The Chinese mantra may be that the world is big enough for China and India to develop simultaneously but the military standoff has made it clear that aside from diplomatic courtesies the hard reality of geopolitics present a very different picture. India considers China its main rival. One should not forget Vajpayee’s letter to the US president, terming China as the main threat and reason behind Indian nuclear tests in 1998. India has not emerged from that kind of thinking. To an extent, China’s rapid development has strengthened these Indian concerns.

Moreover, despite frantic diplomacy over the decades, both sides have not made any meaningful progress on their long-standing unmarked border. The disputed territory is almost five times the size of Taiwan. New Delhi is in no mood to withdraw an inch from what is under its control. Negotiations for a border settlement, to India, is akin to talking about what is under China’s control. In fact, instead of settling the traditional territorial dispute, over the years new challenges of a geopolitical nature have emerged between the two sides.

Thus, Indian action in Chinese territory which caused the Doklam standoff has far-reaching implications. It was an Indian attempt to solve the issue through military means which damaged the already weak Sino-Indian trust, threw cold water on BRICS and set a dangerous precedent of military intervention by violating international boundaries. The decision on August 29 to withdraw forces from the Doklam Plateau just shelved the conflict and did not solve it.

Dr Ghulam Ali teaches International Relations at the School of Marxism, Sichuan University of Science & Engineering, Zigong, China. The views expressed are his personal. He is the author of China-Pakistan Relations: A Historical Analysis (OUP 2017) ghulamali74@yahoo.com