The provisional results of the 2017 Census show that since 1998 Punjab’s population has increased at the rate of 2.13% per annum, making it the federating unit with the lowest growth, falling 0.37% below the national average. This is significant because the numbers determine how much of a heavyweight you are in government.

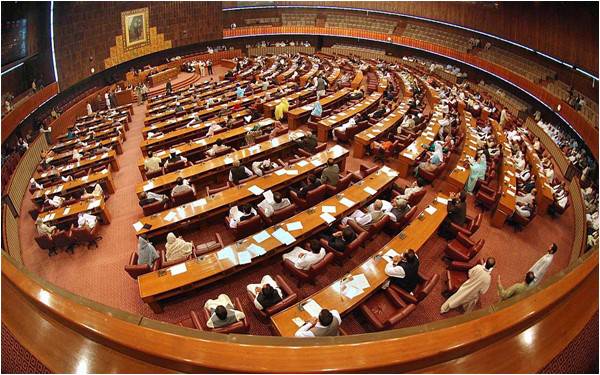

Article 51 of Pakistan’s Constitution says that “seats in the National Assembly are to be allocated to each province, Federally Administered Tribal Areas and Federal Capital Territory in accordance with the last preceding census officially published.” Therefore, Punjab gets 148 out of the 272 NA seats.

If the population formula given in the Constitution is followed, Punjab could lose up to four NA seats, with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan the likeliest beneficiaries.

Aside from power, the numbers matter when it comes to money as well. The National Finance Commission (NFC) distributes federal revenue according to population as well. Here too, Punjab looks set to lose out on its financial share. That is unless the Constitution, or the NFC Award formula, is amended.

Former caretaker finance minister, and advisor on statistics and revenues, Salman Shah, says that the Punjab government would have to accept the division formula once the formal announcement of the population is confirmed. “As per Pakistan’s Constitution, every citizen has equal rights, which means the equal right to the financial share and equal electoral representation,” he explained. “So the government not accepting any resulting revisions is out of the question.”

Shah believes, however, that the NFC Award formula might still be revisited. “There are other factors other than population that impact distribution; development being one of them. And so the NFC formula can be revised as long as the motivation isn’t political, but data-driven.”

Other analysts believe that the NFC is well-defined and doesn’t need any tinkering. “We just need to put in the new data, and everything will adjust itself accordingly,” says economist Dr Kaiser Bengali, a former director of the Social Policy and Development Center, Karachi and Sustainable Development Policy Institute, Islamabad. “So the formula won’t be revised, just the coefficient for each federating unit would be revised as per new population stats.”

Dr Bengali says there are two ways to update the coefficient. “The first is to call an NFC meeting and take the decision. The second is if the PM sends a summary to the President to approve it. Even after the NFC meeting, a summary would have to go to the President for approval.”

Rural-urban divide

In addition to power and money, the new census data also affects how a province will look at itself and plan. For all provinces, then, a major concern is the movement of people (or lack thereof) from the countryside to the cities.

The provisional summary presented in the Council of Common Interests highlighted that of the 207,744,520 people in Pakistan 132,189,531 live in rural and 75,584,989 in urban areas. This means that there is almost a 10% hike in the urban population. Around 37% of Pakistan is therefore urban. “The Punjab government would now have to balance its development of the urban centres, designed to lure the population towards them and bolster the vote banks, by reconsidering their policies in the rural areas,” says a retired senior Punjab Civil Service officer. “This would mean finally challenging the monopoly that landlords have in the rural areas. But the issue here is that neither the pockets nor the vote boxes would be filled without these landlords’ support. So both the bureaucracy and the ruling party would have to compromise on its own interests to cater to the interests of the rural masses,” he explained.

Salman Shah believes, however, that recent projects taken up by the government necessitate that population distribution won’t be the limiting factor, and other aspects would also be taken into consideration. “With the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, there is a lot of development in areas where population is sparse,” he said. “This means a simultaneous increase in urbanisation, but at the same time rural areas are being developed to support the infrastructural projects that are a part of CPEC, and other plans that the government has undertaken.”

Dr Bengali had a word of caution. He believes that Pakistani governments are accustomed to putting the ‘cart before the horse.’ “We don’t have policymaking for there to be a shift,” he argued. “Had there been any policies in play, there wouldn’t have been such runaway growth [in the first place]. There is no urbanization policy. Cities are dumping grounds for surplus agricultural labour. If there is a growth in urban population, they need to give them housing, jobs, health and other services.”

Article 51 of Pakistan’s Constitution says that “seats in the National Assembly are to be allocated to each province, Federally Administered Tribal Areas and Federal Capital Territory in accordance with the last preceding census officially published.” Therefore, Punjab gets 148 out of the 272 NA seats.

If the population formula given in the Constitution is followed, Punjab could lose up to four NA seats, with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan the likeliest beneficiaries.

Aside from power, the numbers matter when it comes to money as well. The National Finance Commission (NFC) distributes federal revenue according to population as well. Here too, Punjab looks set to lose out on its financial share. That is unless the Constitution, or the NFC Award formula, is amended.

There is no urbanization policy. Cities are dumping grounds for surplus agricultural labour

Former caretaker finance minister, and advisor on statistics and revenues, Salman Shah, says that the Punjab government would have to accept the division formula once the formal announcement of the population is confirmed. “As per Pakistan’s Constitution, every citizen has equal rights, which means the equal right to the financial share and equal electoral representation,” he explained. “So the government not accepting any resulting revisions is out of the question.”

Shah believes, however, that the NFC Award formula might still be revisited. “There are other factors other than population that impact distribution; development being one of them. And so the NFC formula can be revised as long as the motivation isn’t political, but data-driven.”

Other analysts believe that the NFC is well-defined and doesn’t need any tinkering. “We just need to put in the new data, and everything will adjust itself accordingly,” says economist Dr Kaiser Bengali, a former director of the Social Policy and Development Center, Karachi and Sustainable Development Policy Institute, Islamabad. “So the formula won’t be revised, just the coefficient for each federating unit would be revised as per new population stats.”

Dr Bengali says there are two ways to update the coefficient. “The first is to call an NFC meeting and take the decision. The second is if the PM sends a summary to the President to approve it. Even after the NFC meeting, a summary would have to go to the President for approval.”

Rural-urban divide

In addition to power and money, the new census data also affects how a province will look at itself and plan. For all provinces, then, a major concern is the movement of people (or lack thereof) from the countryside to the cities.

The provisional summary presented in the Council of Common Interests highlighted that of the 207,744,520 people in Pakistan 132,189,531 live in rural and 75,584,989 in urban areas. This means that there is almost a 10% hike in the urban population. Around 37% of Pakistan is therefore urban. “The Punjab government would now have to balance its development of the urban centres, designed to lure the population towards them and bolster the vote banks, by reconsidering their policies in the rural areas,” says a retired senior Punjab Civil Service officer. “This would mean finally challenging the monopoly that landlords have in the rural areas. But the issue here is that neither the pockets nor the vote boxes would be filled without these landlords’ support. So both the bureaucracy and the ruling party would have to compromise on its own interests to cater to the interests of the rural masses,” he explained.

Salman Shah believes, however, that recent projects taken up by the government necessitate that population distribution won’t be the limiting factor, and other aspects would also be taken into consideration. “With the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, there is a lot of development in areas where population is sparse,” he said. “This means a simultaneous increase in urbanisation, but at the same time rural areas are being developed to support the infrastructural projects that are a part of CPEC, and other plans that the government has undertaken.”

Dr Bengali had a word of caution. He believes that Pakistani governments are accustomed to putting the ‘cart before the horse.’ “We don’t have policymaking for there to be a shift,” he argued. “Had there been any policies in play, there wouldn’t have been such runaway growth [in the first place]. There is no urbanization policy. Cities are dumping grounds for surplus agricultural labour. If there is a growth in urban population, they need to give them housing, jobs, health and other services.”