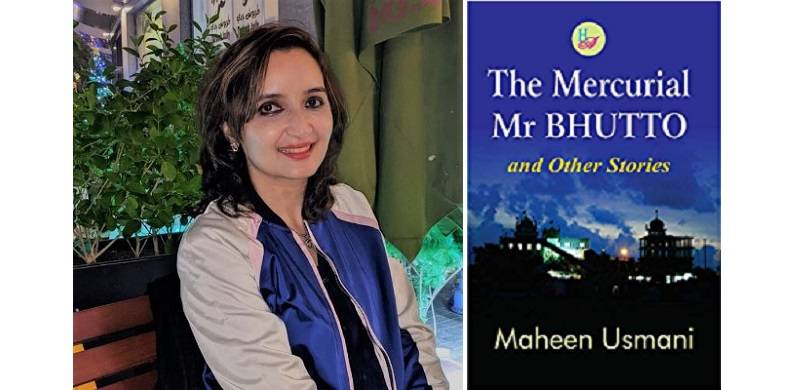

Maheen Usmani is the author of a collection of short stories titled The Mercurial Mr Bhutto and Other Stories. An award-winning journalist, she has worked for the print and electronic media, and penned columns and features that reflect her deep concern about the injustices that plague society. She has also made a series of investigative documentaries on the fall of Dhaka and the murder of former premier Zulfikar Ali Bhutto.

In this conversation, Maheen discusses her experience of navigating the disparate world of fictional and journalistic writing, and her decision to opt for short stories instead of the novel. Maheen also discusses the impetus for the varied tales and her aversion to moralistic storytelling.

TK: What was the inspiration for The Mercurial Mr Bhutto and Other Stories?

Maheen Usmani: I had been planning to write a novel for a long time. But the plot became too clunky and resembled that of a classic Russian novel that people once used to read. So, I decided to write short stories and, therefore, started writing The Mercurial Mr Bhutto and Other Stories.

It took some time as I didn’t know which stories I’d include in the book. I was more interested in ideas that I identified most with rather than those that were popular in the market. You may have noticed that the stories in the collection are quite different from each other and some of the topics they deal with haven’t been written about by Pakistani writers. The inspiration for the book was my desire to write about issues that were close to my heart.

TK: Was it difficult to make a transition from journalistic writing to fiction? How different is fiction from fact-driven journalistic writing?

MU: It’s difficult because you have to decide what you intend to write about. Journalistic writing is more about recording what is happening in front of us while fiction requires us to come up with characters and a plot.

Even so, I did end up using some of my journalistic experiences to write fiction. For example, 15 Minutes of Fame makes a comment on media ethics nowadays and how journalists chase after stories and show little compassion for the subjects they are covering.

When I was working as a journalist, I wasn’t allowed to cover too many human-interest stories because, much to my frustration, all the airtime was given to political reporting. I used to argue with my bosses about why so much coverage was given to the speeches of politicians and little or no attention was given to women’s rights, education, minority rights and climate change. I was eventually told that I could report on any issue I deemed fit, but wouldn’t be given more than one or two minutes.

This was absurd as I couldn’t possibly cover serious issues in such a limited duration. If I prepared a three-minute-long report, it would be cut down. I was frequently told that audiences wanted to watch political news and I should be grateful for the rather limited time I’d gained to report on these issues. Nevertheless, I worked hard on these packages and became quite good at distilling information into very brief reports, which probably helped me in writing my short stories. It’s easy to write a thesis, but the real skill involves distilling what you want to say in a concise manner.

But I always felt that I wasn’t getting a chance to fulfill my true potential. When I started doing investigative reports, I was assigned stories that dealt with political issues, such as the separation of East Pakistan in 1971. I pushed myself to do the occasional human-interest story. For instance, I worked on a report on human trafficking of people from Punjab, which was somewhat difficult as I had to report from Daska, where you barely get to see women in public spaces.

Even when I was working as a journalist, I used to keep thinking about writing stories. Though I never got the time to write them, they were percolating in my mind like coffee brews on a stove. It came to a point when I thought my head would burst if I didn't write those stories down. I used to write blogs and features that used to face censorship at the hands of editors who would spoil the essence of a piece. I realised one day that I didn’t need to write for others when I could write for myself. That way I could discuss issues that were important to me. Overall, my journalistic career gave me lots of ideas and the ability to read situations. It also taught me how to observe – an important skill for a journalist and writer. I like to think of myself as a fly on the wall and often blend into the crowd.

TK: Do you find short stories to be a more powerful form than the novel?

MU: I realised later that I had made a mistake since short stories are very difficult to write. I wrote short stories, because I had far too many tales for a novel and the plot seemed a bit convoluted. Nevertheless, short stories are a great form of storytelling. I have been influenced by Saadat Hassan Manto, who wrote stories that were brief but had so much impact. I used to read classic short story writers such as Guy de Maupassant and Chekhov. Maupassant has an amazing short story called ‘The Necklace’, which left a deep impression on me. Even now, I go back to it because I find it so fascinating.

By reading these writers, I learnt how to keep a story brief and to get into the minds of my characters. For instance, Maupassant succeeds in getting into the mind of a lowly government servant’s wife and writing about how she thinks. It seems as if the writer disappears from the page and the character remains to tell the story. I used this technique in my own stories because I like the idea of stepping into a character’s shoes and seeing things from his/her point of view.

Writers don’t necessarily have to agree with the character’s beliefs and values. They often make the mistake of sounding moralistic and sermonizing through fiction, and appear to be disapproving of the character's behaviour. Writers such as Vikram Seth and Jane Austen tell their stories from the character’s point of view. Only good writers know how to do this. Furthermore, Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina is written in a way that helps readers understand the main character’s motivations for seeking a another man’s company and being torn between him and her son. Usually male writers aren’t able to portray women with empathy.

I try to avoid a moralistic approach to storytelling in my work and keep my stories short because I want to leave it up to the intelligence of the reader to decipher what a story is about. For instance, Maupassant’s ‘The Necklace’ allows the reader to interpret a situation on their own terms. My stories also contain plot twists to avoid being run-of-the-mill and mundane.

TK: In the title story, you've examined former prime minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto's regime through a child's perspective. How did this creative choice impact the story?

MU: The reason I opted for a child’s perspective was that we rarely come across a child narrator in books by Pakistani writers. When a child is at the centre of a story by a Pakistani writer, he or she usually grows up during the course of the book. Children are also very observant and individuals in their own right, which we rarely acknowledge.

I often heard about Zulfikar Ali Bhutto from my father. I used to hear different narratives about that time, but wasn’t too interested in them as I was very apolitical. When I was asked to do a report on the extrajudicial murder of Bhutto, I didn’t know much about the subject beyond the basics. That compelled me to read up on the issue and critically analyse the facts. I also spoke to my father because he had met Bhutto a few times and had witnessed the period when he had been put on trial.

My father told me things that I hadn’t read in any book. He was a bureaucrat who was known to be very objective and principled so I believe that what he told me was the unvarnished truth. For instance, my father mentioned that there was hardly any street agitation after Bhutto was hanged – which goes against what some of his supporters and party activists say about that period. I asked him to confirm other things that I’d read in the press or through Facebook posts. My father told me that those were lies. When I asked why people would lie about such things, he said that ideology can make people lie. He also told me that many sections of the press collaborated with General Zia to bring down Bhutto -- something that I hadn’t heard before.

I decided to investigate further on that particular era because I realised that the narratives that we’d been fed about that time were a façade that was built up over years and we didn’t have the gumption, foresight and initiative to read up on the matter.

The stories my father told me had a deep impact on me. Even though I didn’t instantly write them down, I remembered them. When I started writing my short stories, ‘The Mercurial Mr Bhutto’ was the first story I wrote and I wanted to incorporate some of my father's observations. I used a ‘non-fiction character’ (ie Bhutto) and had fictional characters tell his story. Bhutto isn’t present in the story and readers only observe him through the characters and the setting.

I wanted to write about what Bhutto died for and why he’s called a martyr. In the story, I have shown that there were people who believed in General Zia. For instance, there were student leaders who cheered him on. I also wanted to write about the doctors who took a stand during the Zia years by refusing to perform amputations in public – a fact that my father told me about. I was curious about what a doctor who had once been a student leader who had welcomed martial law would think after Zia changed the fabric of the nation.

TK: 'City of Light' resonates deeply with the citizens of Karachi as it offers a humorous take on the power crisis. Is humour an important ingredient to living and writing about a chaotic city like Karachi?

MU: If you live in Karachi and don’t laugh, you’ll go insane and become an embittered husk of a human being. In Karachi, you deal with all kinds of situations that will make you bang your head against the wall. A generator is as precious as gold, if not more.

You have to look at the funny side of things. This has helped Karachiites develop a stronger sense of humour than people from other cities. In a city like Karachi, you need to have a Plan-B for everthing.

TK: '15 Minutes of Fame' is a telling example of absurdist fiction. How did this story come about? Do you believe that this genre is neglected in Pakistani literature?

MU: This form of writing is essential and writers have been producing such work for centuries. However, there isn’t much fiction in Pakistan that falls into this genre.

I came across an interview in a newspaper of an economist who taught at IBA. One day, he went to McDonalds in Karachi and came across one of his students who was working there because he couldn’t find a job. I decided to write about this incident because I came across many talented and educated people who remained unemployed. This problem is interconnected with so many other issues in our society.

In addition, there was another real-life incident that had an impact on me. A university graduate went for a job interview, and lost his life after a fire broke out and he fell from the building. The media persons who had gathered around the area didn’t do anything to save him. It was horrifying because the media kept showing footage of him falling from the building and circling his body with cameras when it landed on the ground.

The coverage disturbed me and I wanted to write something about it, to depict how the media glamorizes people’s suffering for the sake of ratings without caring about the sensitivities of their family.

When I finally wrote '15 Minutes of Fame’, I put myself in that man’s shoes and tried to visualize his life. Apart from the lack of media ethics, I wanted to depict how things don’t always go as planned and your life can change, because you are in the wrong place at the wrong time.

'15 Minutes of Fame' obviously comes from a well-known saying that suggests that everyone has their moment of fame, but we don’t always know what kind of fame we will enjoy. We don’t know if we’ll be truly famous in the right sense of the word. Nowadays the lines between the two have been blurred and nobody cares even if you’re famous for being notorious.

TK: In 'Home Sweet Home', a bureaucrat offers a well-meaning complaint about his wife's expenditure on their house. How different would the narrative be if it was told from the point of view of the bureaucrat's wife?

MU: I should make it clear that this story is about an honest bureaucrat and not a corrupt one. The bureaucrat's wife would consider her husband’s views on the costs of constructing the house to be completely unjustified because spending on building a comfortable home is necessary. As the wife of a bureaucrat, she is accustomed to living in government houses where various facilities and amenities are available. How can she be expected to live in a smaller house that resembles a cubby hole or a chicken coop? She would probably ask him to spend more on the house to ensure her comfort. If the husband tried to assure her that he’s spent all his savings on building the house, she wouldn’t believe him.

The bureaucrat’s wife is possibly part of a wide social circle that often entertains guests at home. A majority of the people who belong to this group consists of jet-setters and the elite. A bureaucrat’s wife doesn’t usually have the money to invite her friends to a dinner at Café Flo and would prefer having a dinner party at her own house. Therefore, she needs to have a bigger house where she can invite her friends. She can’t be expected to compromise, not after a lifetime of being conditioned to a particular way of life.

TK: 'Maestro' explores how lack of recognition can stifle creative genius. What was the impetus for this story?

MU: While I’m not an insider of the music industry, I have often seen that it is dominated by a corporate culture. Many singers who wanted to make music on their own were told to join boy bands instead and produce a particular kind of music. With time, singers like Zayn Malik and Harry Styles decided to break away from boy bands when they could afford to do that. In South Korea’s music scene, there is an emphasis on conformity, which is the main reason for the high rate of suicide among celebrities. The members of K-Pop bands have to look and sound a certain way – it’s like an assembly line of music. As a result, originality dies out and singers become frustrated.

For a musician who is a creative genius, it is difficult to kill his/her distinct talent and sound like everyone else. In Pakistan, we have the example of the musician and guitarist Amir Zaki who stuck to his guns and didn’t get the recognition that he deserved because he refused to make the same kind of music as other singers. Amir Zaki is one in a million as most people eventually conform because they want the money.

I wrote ‘Maestro’ because I wanted readers to understand the psyche of a creative genius. Nobody tries to understand the creative genius because the reality is that all of us change ourselves and suppress our individuality to fit into society.

I took elements from various sources to write the story. For instance, I drew on the example of Junaid Jamshed, Ali Haider and Amir Zaki. I wanted to explore why a musician who is a creative genius is not allowed to do what he wants to do. At the same time, I wanted to show what happens to musicians who defy the corporate culture and tread their own path. This is a realistic story and I didn’t want to make it a feel-good story when I wrote it. Musicians end up compromising at some level. A creative genius, who is not flexible and views the corporate culture as an insult to his/her art, has to struggle to survive in the business.

TK: 'Fifty Shades of Grief' is a moving meditation on human foibles. The story is especially memorable for its explosive ending. Did you chance upon the ending while writing the story or was it pre-planned?

MU: I had to really think about this story before I began writing it. ‘Fifty Shades of Grief’ stemmed from a few real-life incidents. I attended a few funerals and noticed the way people spoke and dressed. Women were dressed in a sombre way, but kept gossiping and chatting, especially while the prayers were being recited.

I recall an incident that occurred once when I rushed from a dinner party to the house of a friend whose relative had died. I was wearing jeans and a shirt, so I borrowed a white shawl from my friend to condole with the bereaved family. Later on, I was told by somebody that I wasn’t dressed appropriately. I asked the person if my attire was expected to reveal how grief-stricken I was. Surely the fact that I left a dinner to be with the bereaved in their hour of need meant something. The person told me that my attire mattered more. Interestingly, a few people I knew told me that they were having white shalwar kameez stitched and embroidered so they could wear them at funerals.

All this made me wonder what people were really thinking at funerals. I started observing people at funerals and wondered if they were genuinely in mourning or observing all the niceties due to a sense of duty. That’s where I got the idea for ‘Fifty Shades of Grief’.

I was also interested in exploring the extent that we can go to for the people we love. Are people willing to commit murder in the name of love? I wasn’t examining the mentality of serial killers, but I wanted to explore the sensibilities of someone who commits murder on a one-off basis. I added the twist to the story at the end because that is how thrillers should be written. The reader should not be able to predict what happens next. It was tough to write this story because I wanted to leave it to the intelligence of readers and not spoon-feed them.

TK: 'Baby' brings to the fore an important conversation about child abuse. Were you mindful of any ethical considerations, such as concerns about trigger warnings, while writing this story?

MU: I tried to write 'Baby' in a sensitive manner and without making it too violent. I wrote about child abuse to draw attention to the injustices associated with the issue.

Child abuse is an important issue that hasn’t been written about by too many contemporary Pakistani writers. Khaled Hossaini’s The Kite Runner tackles the issue with sensitivity and I wanted to see something similar in books from Pakistani writers. Instead of waiting for others to write about it, I decided to write it myself. However, I knew it would be a difficult topic to write about as I feared that my parents might raise objections about the subject matter and not approve of my tackling this theme. Incidentally, they liked the story when it was published.

I deliberately chose to write about a boy who was subjected to child abuse because there isn’t much awareness about the fact that boys also fall prey to these practices.

We often forget that a vast number of cases of child abuse involve predators who are known to the child. That’s frightening because we never know when we’re letting a predator into our house. In most cases, we tend to not believe the child when they mention that they are being abused. But I didn’t want to write the story from the point of view of a mother who doesn’t believe her child. This was written from the perspective of a mother who has experienced child abuse, but never spoke about it. Due to her own past experience, she believes the child when he says that he is being abused -- which doesn’t usually happen.

I tried to write ‘Baby’ in a nuanced manner and didn’t feel the need to introduce trigger warnings as I wrote multiple drafts of the story. I read the story out to myself and put myself in the position of the mother and the child. I even tried to see things from the perspective of the father who might not necessarily react in the way he’s expected to in the situation. I was relieved that reviewers and readers felt that the issue was handled sensitively.

TK: Do you fear that the collection of stories has been judged according to its title?

MU: The reason I chose ‘The Mercurial Mr Bhutto’ as the title story is because I liked it a lot. But I realised that when the book was published that there is intense polarization and hatred towards Bhutto. Many readers were pleased that I’d written about their beloved Bhutto and thought that I supported the Pakistan People’s Party. Others were outraged that I’d written about a leader who, they believed, had wrecked the country. One woman said at my book launch, “It’s sad that you’re writing about Bhutto, but not writing about Imran Khan”. I humoured her and said I’d write my next book about “Khan Sahib”. Another woman stood up at a book event and said she wouldn’t buy my book because it had Bhutto’s name on it. She said that Bhutto is six feet under and that our people should bury his memory as well. The moderator was shocked, but I said: “Haven’t you heard? Bhutto Zinda Hai (Bhutto is Alive)”.

When people ask me why I chose to write about Bhutto, I mention that he was our prime minister and is, therefore, part of our country’s history. How can we possibly erase him and his party from the body politic of Pakistan? People weren’t convinced. Owing to this divisive rhetoric or ideology, we are unable to write biographies of our statesmen and have to rely on the foreign lens for this purpose.

The reaction to the title story made me jokingly tell people that I’d made a mistake by deciding to write about such a divisive figure. The other mistake I made was adding the adjective ‘mercurial’ in the title since many people didn’t know what it meant or how it was pronounced. I told them that next time, I’d just opt for the title ‘The Mr Bhutto’. Naturally, many people didn’t get the joke. If I ever write a story about a political leader again, I am not going to mention his or her name in the title.

TK: How was your experience of publishing in Pakistan?

MU: Publishing in Pakistan is a nightmare and the quality of books published locally falls below par as compared with those that are released in other countries. But the import ban on India and subsequently the pandemic have helped the publishing industry. We have a few new publishing companies now, such as Lightstone Publishing and Reverie Publishers. The disadvantage we had has forced entrepreneurs to come up with solutions within Pakistan. Disruption has led to innovation since a difficult situation has helped create opportunities because it has challenged writers to think out of the box and approach new publishers here instead of playing it safe.

In this conversation, Maheen discusses her experience of navigating the disparate world of fictional and journalistic writing, and her decision to opt for short stories instead of the novel. Maheen also discusses the impetus for the varied tales and her aversion to moralistic storytelling.

TK: What was the inspiration for The Mercurial Mr Bhutto and Other Stories?

Maheen Usmani: I had been planning to write a novel for a long time. But the plot became too clunky and resembled that of a classic Russian novel that people once used to read. So, I decided to write short stories and, therefore, started writing The Mercurial Mr Bhutto and Other Stories.

It took some time as I didn’t know which stories I’d include in the book. I was more interested in ideas that I identified most with rather than those that were popular in the market. You may have noticed that the stories in the collection are quite different from each other and some of the topics they deal with haven’t been written about by Pakistani writers. The inspiration for the book was my desire to write about issues that were close to my heart.

TK: Was it difficult to make a transition from journalistic writing to fiction? How different is fiction from fact-driven journalistic writing?

MU: It’s difficult because you have to decide what you intend to write about. Journalistic writing is more about recording what is happening in front of us while fiction requires us to come up with characters and a plot.

Even so, I did end up using some of my journalistic experiences to write fiction. For example, 15 Minutes of Fame makes a comment on media ethics nowadays and how journalists chase after stories and show little compassion for the subjects they are covering.

When I was working as a journalist, I wasn’t allowed to cover too many human-interest stories because, much to my frustration, all the airtime was given to political reporting. I used to argue with my bosses about why so much coverage was given to the speeches of politicians and little or no attention was given to women’s rights, education, minority rights and climate change. I was eventually told that I could report on any issue I deemed fit, but wouldn’t be given more than one or two minutes.

This was absurd as I couldn’t possibly cover serious issues in such a limited duration. If I prepared a three-minute-long report, it would be cut down. I was frequently told that audiences wanted to watch political news and I should be grateful for the rather limited time I’d gained to report on these issues. Nevertheless, I worked hard on these packages and became quite good at distilling information into very brief reports, which probably helped me in writing my short stories. It’s easy to write a thesis, but the real skill involves distilling what you want to say in a concise manner.

But I always felt that I wasn’t getting a chance to fulfill my true potential. When I started doing investigative reports, I was assigned stories that dealt with political issues, such as the separation of East Pakistan in 1971. I pushed myself to do the occasional human-interest story. For instance, I worked on a report on human trafficking of people from Punjab, which was somewhat difficult as I had to report from Daska, where you barely get to see women in public spaces.

Even when I was working as a journalist, I used to keep thinking about writing stories. Though I never got the time to write them, they were percolating in my mind like coffee brews on a stove. It came to a point when I thought my head would burst if I didn't write those stories down. I used to write blogs and features that used to face censorship at the hands of editors who would spoil the essence of a piece. I realised one day that I didn’t need to write for others when I could write for myself. That way I could discuss issues that were important to me. Overall, my journalistic career gave me lots of ideas and the ability to read situations. It also taught me how to observe – an important skill for a journalist and writer. I like to think of myself as a fly on the wall and often blend into the crowd.

"When people ask me why I chose to write about Bhutto, I mention that he was our prime minister and is, therefore, part of our country’s history. How can we possibly erase him and his party from the body politic of Pakistan? People weren’t convinced. Owing to this divisive rhetoric or ideology, we are unable to write biographies of our statesmen and have to rely on the foreign lens"

TK: Do you find short stories to be a more powerful form than the novel?

MU: I realised later that I had made a mistake since short stories are very difficult to write. I wrote short stories, because I had far too many tales for a novel and the plot seemed a bit convoluted. Nevertheless, short stories are a great form of storytelling. I have been influenced by Saadat Hassan Manto, who wrote stories that were brief but had so much impact. I used to read classic short story writers such as Guy de Maupassant and Chekhov. Maupassant has an amazing short story called ‘The Necklace’, which left a deep impression on me. Even now, I go back to it because I find it so fascinating.

By reading these writers, I learnt how to keep a story brief and to get into the minds of my characters. For instance, Maupassant succeeds in getting into the mind of a lowly government servant’s wife and writing about how she thinks. It seems as if the writer disappears from the page and the character remains to tell the story. I used this technique in my own stories because I like the idea of stepping into a character’s shoes and seeing things from his/her point of view.

Writers don’t necessarily have to agree with the character’s beliefs and values. They often make the mistake of sounding moralistic and sermonizing through fiction, and appear to be disapproving of the character's behaviour. Writers such as Vikram Seth and Jane Austen tell their stories from the character’s point of view. Only good writers know how to do this. Furthermore, Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina is written in a way that helps readers understand the main character’s motivations for seeking a another man’s company and being torn between him and her son. Usually male writers aren’t able to portray women with empathy.

I try to avoid a moralistic approach to storytelling in my work and keep my stories short because I want to leave it up to the intelligence of the reader to decipher what a story is about. For instance, Maupassant’s ‘The Necklace’ allows the reader to interpret a situation on their own terms. My stories also contain plot twists to avoid being run-of-the-mill and mundane.

TK: In the title story, you've examined former prime minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto's regime through a child's perspective. How did this creative choice impact the story?

MU: The reason I opted for a child’s perspective was that we rarely come across a child narrator in books by Pakistani writers. When a child is at the centre of a story by a Pakistani writer, he or she usually grows up during the course of the book. Children are also very observant and individuals in their own right, which we rarely acknowledge.

I often heard about Zulfikar Ali Bhutto from my father. I used to hear different narratives about that time, but wasn’t too interested in them as I was very apolitical. When I was asked to do a report on the extrajudicial murder of Bhutto, I didn’t know much about the subject beyond the basics. That compelled me to read up on the issue and critically analyse the facts. I also spoke to my father because he had met Bhutto a few times and had witnessed the period when he had been put on trial.

My father told me things that I hadn’t read in any book. He was a bureaucrat who was known to be very objective and principled so I believe that what he told me was the unvarnished truth. For instance, my father mentioned that there was hardly any street agitation after Bhutto was hanged – which goes against what some of his supporters and party activists say about that period. I asked him to confirm other things that I’d read in the press or through Facebook posts. My father told me that those were lies. When I asked why people would lie about such things, he said that ideology can make people lie. He also told me that many sections of the press collaborated with General Zia to bring down Bhutto -- something that I hadn’t heard before.

I decided to investigate further on that particular era because I realised that the narratives that we’d been fed about that time were a façade that was built up over years and we didn’t have the gumption, foresight and initiative to read up on the matter.

The stories my father told me had a deep impact on me. Even though I didn’t instantly write them down, I remembered them. When I started writing my short stories, ‘The Mercurial Mr Bhutto’ was the first story I wrote and I wanted to incorporate some of my father's observations. I used a ‘non-fiction character’ (ie Bhutto) and had fictional characters tell his story. Bhutto isn’t present in the story and readers only observe him through the characters and the setting.

I wanted to write about what Bhutto died for and why he’s called a martyr. In the story, I have shown that there were people who believed in General Zia. For instance, there were student leaders who cheered him on. I also wanted to write about the doctors who took a stand during the Zia years by refusing to perform amputations in public – a fact that my father told me about. I was curious about what a doctor who had once been a student leader who had welcomed martial law would think after Zia changed the fabric of the nation.

"I realised later that I had made a mistake since short stories are very difficult to write. I wrote short stories, because I had far too many tales for a novel and the plot seemed a bit convoluted. Nevertheless, short stories are a great form of storytelling"

TK: 'City of Light' resonates deeply with the citizens of Karachi as it offers a humorous take on the power crisis. Is humour an important ingredient to living and writing about a chaotic city like Karachi?

MU: If you live in Karachi and don’t laugh, you’ll go insane and become an embittered husk of a human being. In Karachi, you deal with all kinds of situations that will make you bang your head against the wall. A generator is as precious as gold, if not more.

You have to look at the funny side of things. This has helped Karachiites develop a stronger sense of humour than people from other cities. In a city like Karachi, you need to have a Plan-B for everthing.

TK: '15 Minutes of Fame' is a telling example of absurdist fiction. How did this story come about? Do you believe that this genre is neglected in Pakistani literature?

MU: This form of writing is essential and writers have been producing such work for centuries. However, there isn’t much fiction in Pakistan that falls into this genre.

I came across an interview in a newspaper of an economist who taught at IBA. One day, he went to McDonalds in Karachi and came across one of his students who was working there because he couldn’t find a job. I decided to write about this incident because I came across many talented and educated people who remained unemployed. This problem is interconnected with so many other issues in our society.

In addition, there was another real-life incident that had an impact on me. A university graduate went for a job interview, and lost his life after a fire broke out and he fell from the building. The media persons who had gathered around the area didn’t do anything to save him. It was horrifying because the media kept showing footage of him falling from the building and circling his body with cameras when it landed on the ground.

The coverage disturbed me and I wanted to write something about it, to depict how the media glamorizes people’s suffering for the sake of ratings without caring about the sensitivities of their family.

When I finally wrote '15 Minutes of Fame’, I put myself in that man’s shoes and tried to visualize his life. Apart from the lack of media ethics, I wanted to depict how things don’t always go as planned and your life can change, because you are in the wrong place at the wrong time.

'15 Minutes of Fame' obviously comes from a well-known saying that suggests that everyone has their moment of fame, but we don’t always know what kind of fame we will enjoy. We don’t know if we’ll be truly famous in the right sense of the word. Nowadays the lines between the two have been blurred and nobody cares even if you’re famous for being notorious.

TK: In 'Home Sweet Home', a bureaucrat offers a well-meaning complaint about his wife's expenditure on their house. How different would the narrative be if it was told from the point of view of the bureaucrat's wife?

MU: I should make it clear that this story is about an honest bureaucrat and not a corrupt one. The bureaucrat's wife would consider her husband’s views on the costs of constructing the house to be completely unjustified because spending on building a comfortable home is necessary. As the wife of a bureaucrat, she is accustomed to living in government houses where various facilities and amenities are available. How can she be expected to live in a smaller house that resembles a cubby hole or a chicken coop? She would probably ask him to spend more on the house to ensure her comfort. If the husband tried to assure her that he’s spent all his savings on building the house, she wouldn’t believe him.

The bureaucrat’s wife is possibly part of a wide social circle that often entertains guests at home. A majority of the people who belong to this group consists of jet-setters and the elite. A bureaucrat’s wife doesn’t usually have the money to invite her friends to a dinner at Café Flo and would prefer having a dinner party at her own house. Therefore, she needs to have a bigger house where she can invite her friends. She can’t be expected to compromise, not after a lifetime of being conditioned to a particular way of life.

TK: 'Maestro' explores how lack of recognition can stifle creative genius. What was the impetus for this story?

MU: While I’m not an insider of the music industry, I have often seen that it is dominated by a corporate culture. Many singers who wanted to make music on their own were told to join boy bands instead and produce a particular kind of music. With time, singers like Zayn Malik and Harry Styles decided to break away from boy bands when they could afford to do that. In South Korea’s music scene, there is an emphasis on conformity, which is the main reason for the high rate of suicide among celebrities. The members of K-Pop bands have to look and sound a certain way – it’s like an assembly line of music. As a result, originality dies out and singers become frustrated.

For a musician who is a creative genius, it is difficult to kill his/her distinct talent and sound like everyone else. In Pakistan, we have the example of the musician and guitarist Amir Zaki who stuck to his guns and didn’t get the recognition that he deserved because he refused to make the same kind of music as other singers. Amir Zaki is one in a million as most people eventually conform because they want the money.

I wrote ‘Maestro’ because I wanted readers to understand the psyche of a creative genius. Nobody tries to understand the creative genius because the reality is that all of us change ourselves and suppress our individuality to fit into society.

I took elements from various sources to write the story. For instance, I drew on the example of Junaid Jamshed, Ali Haider and Amir Zaki. I wanted to explore why a musician who is a creative genius is not allowed to do what he wants to do. At the same time, I wanted to show what happens to musicians who defy the corporate culture and tread their own path. This is a realistic story and I didn’t want to make it a feel-good story when I wrote it. Musicians end up compromising at some level. A creative genius, who is not flexible and views the corporate culture as an insult to his/her art, has to struggle to survive in the business.

"I try to avoid a moralistic approach to storytelling in my work and keep my stories short because I want to leave it up to the intelligence of the reader to decipher what a story is about. For instance, Maupassant’s ‘The Necklace’ allows the reader to interpret a situation on their own terms"

TK: 'Fifty Shades of Grief' is a moving meditation on human foibles. The story is especially memorable for its explosive ending. Did you chance upon the ending while writing the story or was it pre-planned?

MU: I had to really think about this story before I began writing it. ‘Fifty Shades of Grief’ stemmed from a few real-life incidents. I attended a few funerals and noticed the way people spoke and dressed. Women were dressed in a sombre way, but kept gossiping and chatting, especially while the prayers were being recited.

I recall an incident that occurred once when I rushed from a dinner party to the house of a friend whose relative had died. I was wearing jeans and a shirt, so I borrowed a white shawl from my friend to condole with the bereaved family. Later on, I was told by somebody that I wasn’t dressed appropriately. I asked the person if my attire was expected to reveal how grief-stricken I was. Surely the fact that I left a dinner to be with the bereaved in their hour of need meant something. The person told me that my attire mattered more. Interestingly, a few people I knew told me that they were having white shalwar kameez stitched and embroidered so they could wear them at funerals.

All this made me wonder what people were really thinking at funerals. I started observing people at funerals and wondered if they were genuinely in mourning or observing all the niceties due to a sense of duty. That’s where I got the idea for ‘Fifty Shades of Grief’.

I was also interested in exploring the extent that we can go to for the people we love. Are people willing to commit murder in the name of love? I wasn’t examining the mentality of serial killers, but I wanted to explore the sensibilities of someone who commits murder on a one-off basis. I added the twist to the story at the end because that is how thrillers should be written. The reader should not be able to predict what happens next. It was tough to write this story because I wanted to leave it to the intelligence of readers and not spoon-feed them.

TK: 'Baby' brings to the fore an important conversation about child abuse. Were you mindful of any ethical considerations, such as concerns about trigger warnings, while writing this story?

MU: I tried to write 'Baby' in a sensitive manner and without making it too violent. I wrote about child abuse to draw attention to the injustices associated with the issue.

Child abuse is an important issue that hasn’t been written about by too many contemporary Pakistani writers. Khaled Hossaini’s The Kite Runner tackles the issue with sensitivity and I wanted to see something similar in books from Pakistani writers. Instead of waiting for others to write about it, I decided to write it myself. However, I knew it would be a difficult topic to write about as I feared that my parents might raise objections about the subject matter and not approve of my tackling this theme. Incidentally, they liked the story when it was published.

I deliberately chose to write about a boy who was subjected to child abuse because there isn’t much awareness about the fact that boys also fall prey to these practices.

We often forget that a vast number of cases of child abuse involve predators who are known to the child. That’s frightening because we never know when we’re letting a predator into our house. In most cases, we tend to not believe the child when they mention that they are being abused. But I didn’t want to write the story from the point of view of a mother who doesn’t believe her child. This was written from the perspective of a mother who has experienced child abuse, but never spoke about it. Due to her own past experience, she believes the child when he says that he is being abused -- which doesn’t usually happen.

I tried to write ‘Baby’ in a nuanced manner and didn’t feel the need to introduce trigger warnings as I wrote multiple drafts of the story. I read the story out to myself and put myself in the position of the mother and the child. I even tried to see things from the perspective of the father who might not necessarily react in the way he’s expected to in the situation. I was relieved that reviewers and readers felt that the issue was handled sensitively.

TK: Do you fear that the collection of stories has been judged according to its title?

MU: The reason I chose ‘The Mercurial Mr Bhutto’ as the title story is because I liked it a lot. But I realised that when the book was published that there is intense polarization and hatred towards Bhutto. Many readers were pleased that I’d written about their beloved Bhutto and thought that I supported the Pakistan People’s Party. Others were outraged that I’d written about a leader who, they believed, had wrecked the country. One woman said at my book launch, “It’s sad that you’re writing about Bhutto, but not writing about Imran Khan”. I humoured her and said I’d write my next book about “Khan Sahib”. Another woman stood up at a book event and said she wouldn’t buy my book because it had Bhutto’s name on it. She said that Bhutto is six feet under and that our people should bury his memory as well. The moderator was shocked, but I said: “Haven’t you heard? Bhutto Zinda Hai (Bhutto is Alive)”.

When people ask me why I chose to write about Bhutto, I mention that he was our prime minister and is, therefore, part of our country’s history. How can we possibly erase him and his party from the body politic of Pakistan? People weren’t convinced. Owing to this divisive rhetoric or ideology, we are unable to write biographies of our statesmen and have to rely on the foreign lens for this purpose.

The reaction to the title story made me jokingly tell people that I’d made a mistake by deciding to write about such a divisive figure. The other mistake I made was adding the adjective ‘mercurial’ in the title since many people didn’t know what it meant or how it was pronounced. I told them that next time, I’d just opt for the title ‘The Mr Bhutto’. Naturally, many people didn’t get the joke. If I ever write a story about a political leader again, I am not going to mention his or her name in the title.

TK: How was your experience of publishing in Pakistan?

MU: Publishing in Pakistan is a nightmare and the quality of books published locally falls below par as compared with those that are released in other countries. But the import ban on India and subsequently the pandemic have helped the publishing industry. We have a few new publishing companies now, such as Lightstone Publishing and Reverie Publishers. The disadvantage we had has forced entrepreneurs to come up with solutions within Pakistan. Disruption has led to innovation since a difficult situation has helped create opportunities because it has challenged writers to think out of the box and approach new publishers here instead of playing it safe.