This is first in a series of articles on child marriages.

The act of forcing children into marriage is a violation of human rights that also undermines the victims' access to basic human needs (life, nutrition, safety), the foundation of well-being (education and health) and opportunities (rights, equality, inclusiveness and freedom of choice) for the girl child. Boys are also married as children, but girls are disproportionately affected.

According to global research, child marriage is severely harmful for girls. In instances of child marriage, neither the girl child’s consent nor age is taken into account. Married children, especially girls, often drop out of school and are locked in a vicious poverty cycle – from parental to marital home – as a result. In Pakistan, women tend to marry earlier than men. Most women (47%) as compared to men (14%) are married by the age of 20. Most of these women (29%) get married between the ages of 18 and 20.

The International Convention on Child Right (ICCR) defines a child to be below 18 years of age. It sets standards for education, health care, social services and penal laws, and establishes the right for children to have a say in decisions that affect them. The guiding principle is to have the best interests of the child as a primary consideration in all actions, especially the child’s inherent right to life. Children are neither the property of their parents, nor helpless objects of charity. They are human beings and are the subject of their own rights as an individual, member of a family, and a community, with rights and responsibilities appropriate to his or her age and stage of development. State parties are obligated to ensure the survival and development of the child; and the child’s right to express his or her views freely in all matters affecting the child. The USA and South Sudan are two countries that have not ratified it. Pakistan is a signatory to and has ratified the ICCR.

The United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) defines child marriage as a formal marriage or informal union occurring before the age of 18. More than 650 million living women were married before the age of 18 globally, and 12 million women are married as children each year, with about half of those occurring in Bangladesh, Brazil, Ethiopia, India and Nigeria.[1] More than 40%, or 285 million, women who married before the age of 18 live in South Asia.

The threshold of 18 years of age is defined in several conventions, treaties, and international agreements, including the Convention on the Rights of the Child (ICRC), the Convention on the Elimination of All forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), as well as resolutions of the UN Human Rights Council. The ICRC emphasizes full and informed consent for marriage while recognizing that children do not have that maturity, information or agency to give such consent. UDHR states that consent cannot be free and full when one of the parties involved is not sufficiently mature to make an informed decision about a life partner. Globally, the average legal age of marriage is 17 for boys and 16 for girls, but many countries permit them, particularly for girls, to marry much younger[2]. The average age of consent in European countries[3] is 16 years old, with the lowest age of consent in Estonia at 15 years old. In the USA the minimum age of martial consent is 12 years old with the parents’ permission in some states, while sexual consent is between 16 and 18 years old, also depending on the state. The USA is not signatory to the ICCR, either.

As per UNICEF South Asia has the highest rates of child marriage in the world.[4] Almost half (45%) of all women aged 20-24 years reported being married before the age of 18. Almost one in five girls (17%) are married before the age of 15.

As per UNICEF South Asia has the highest rates of child marriage in the world.[4] Almost half (45%) of all women aged 20-24 years reported being married before the age of 18. Almost one in five girls (17%) are married before the age of 15.

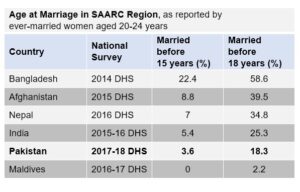

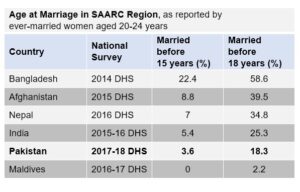

Child marriage is declining but is unable to keep pace with prevalent percentages for population growth. In the South Asian Association for Regional Co-operation (SAARC) countries, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan and Nepal have legally set the marriageable and age of consent at 16 years. While, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives[5] have set it at 18 years. The age of consent for marriage is defined in criminal law in most of the SAARC countries. Pakistan stands at the second lowest age in SAARC.

The SAARC’s Kathmandu call for action in 2014[6] impressed upon member states to:

Acknowledge that child marriage is not merely a social evil but a punishable crime and a human rights violation which triggers a continuum of harms that have a long-term detrimental impact on the lives of girls and women, not just at an individual level but also with regard to countries’ overall socio-economic development and prosperity. Violence against children, especially girls married as children, is not solely a private family matter but a public concern that casts upon States the obligation of due diligence to investigate cases of child marriage, prosecute perpetrators, provide redress to victim.

UNICEF informs that 10 million additional girls are at risk of child marriage due to Covid-19.[7] Pandemic-related mobility restrictions are making it difficult for girls to access the health care, education and social services that can protect them from child marriage, unwanted pregnancy and/or Gender-Based Violence (GBV). Closure of schools is and will contribute to higher school dropout rates for girls, with lower chances of return. Poverty is core driver of child marriage both globally and in Pakistan. The economic impact of Covid-19 (both income and food insecurity) will deepen the impact of poverty that will lead to parents marry their underage daughters to ease financial burdens.

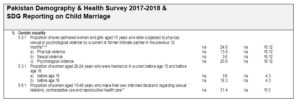

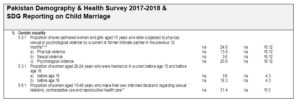

In the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Goal-5 (Target 5.3) compels nations to commit to eliminating “child, early and forced marriages” by 2030, which has been co-opted by Pakistan under an act in parliament. Target 5.3 measures child marriage at two levels i.e. at 15 and 18 years old. Married women in the age cohort of 20-24 years are asked their age of marriage to generate this data, via the Pakistan Demography and Health Survey (PDHS) 2017-2018. Table 4.3 of the PDHS 2017-18 shows that in Pakistan, 3.6% of girls get married under the age of 15 years; and 18.3% girls get married under the age of 18 years

There are many drivers, or factors of child marriage. These are categorized at a social, economic, institutional, legal and policy level. They collectively impact the socio-economic status of an individual and family to result in child marriage. These drivers operate at the state, community, family and individual level and are highly contingent upon local context.

Age and consent are critical to child marriage, which are dependent on birth registration, marriage documentation and above all legal definition of being a child. Under the legal rubric, determination of age is found in different statutes which are not complimentary and allows a girl to be married at 16 years of age; whereas for boys it set the age limit at 18.[8] Education is globally recognized to be a protective factor to stop child marriage, which is demonstrable in Pakistan as well. There is a steady upward gradation in median age at first marriage for women, from 18.7 years for those with no education to 19.8 years for those with primary school education, 22.2 years old for those with secondary education and 24.9 years old for those with higher education.

Pakistan is a patriarchal society with varying degrees of independence for women, as per their socio-economic class and education. The family and clan remain a strong unit of social reference and standing. Parents are primary care givers and financial supporters for children (even after they are of legal age), and hold a socio-religio-accepted position to be the decision maker for their children, including in marriage. A gradual trend of shared decision-making is being recorded for the middle class, but for the upper class and poor it remains unchanged. Poverty, patriarchal structures, harmful socio-customary practices, and economic interest relegate women and the girl child to a low status. Religion as a frame of reference governs aspects of everyday life and behaviour patterns. Quite often, this framing is religio-legitimizing and prevailing customs and traditions are imposed as a means of controlling social narratives, specifically around early and child marriage.

The persistence of child marriage has long-term implications on the life cycle of a girl child, staring with access to basic human needs, the foundation of well-being and opportunities. Girls who marry in childhood face immediate to lifelong consequences. At the outset it usurps their agency and control of their own life. In most cases it takes them out of school and costs them access to education, which has future implications of being able to achieve gainful employment. Families – under religious, cultural or social practices – takeover their consent.

The vulnerability of orphans and stepchildren to child marriage has been reported as high, especially in disaster and conflict areas. Step-daughters and orphan girls are more likely to be married at early ages. At the community level, extended families are involved in the care of orphans and meeting their basic needs through early and middle childhood

Respondents in one study asserted that when orphans reach puberty, guardians may think that their duty of care has been met and that it is acceptable to seek out marriage for non-biological children in the house. [9] Orphans and step children are widely cited as being mistreated or discriminated against. Such treatment renders marriage a more attractive option for girls because they may attempt to run away from what they deem an intolerable living situation.

The health consequences of child marriage are the gravest. Child marriage increases the risk of early and unplanned pregnancy, causing inter-generational health impacts i.e. risk of maternal complications and mortality. With such weak agency and stature, girls in child marriages are more likely to experience domestic violence. Overall, it isolates girls from family and friends and excludes them from participating in their communities, taking a heavy toll on their mental health and well-being.

This policy explainer is derived from United Nations Population Fund (@UNFPAPakistan), population council Pakistan's publications and input from Ms. @shiringul

The act of forcing children into marriage is a violation of human rights that also undermines the victims' access to basic human needs (life, nutrition, safety), the foundation of well-being (education and health) and opportunities (rights, equality, inclusiveness and freedom of choice) for the girl child. Boys are also married as children, but girls are disproportionately affected.

According to global research, child marriage is severely harmful for girls. In instances of child marriage, neither the girl child’s consent nor age is taken into account. Married children, especially girls, often drop out of school and are locked in a vicious poverty cycle – from parental to marital home – as a result. In Pakistan, women tend to marry earlier than men. Most women (47%) as compared to men (14%) are married by the age of 20. Most of these women (29%) get married between the ages of 18 and 20.

The International Convention on Child Right (ICCR) defines a child to be below 18 years of age. It sets standards for education, health care, social services and penal laws, and establishes the right for children to have a say in decisions that affect them. The guiding principle is to have the best interests of the child as a primary consideration in all actions, especially the child’s inherent right to life. Children are neither the property of their parents, nor helpless objects of charity. They are human beings and are the subject of their own rights as an individual, member of a family, and a community, with rights and responsibilities appropriate to his or her age and stage of development. State parties are obligated to ensure the survival and development of the child; and the child’s right to express his or her views freely in all matters affecting the child. The USA and South Sudan are two countries that have not ratified it. Pakistan is a signatory to and has ratified the ICCR.

The United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) defines child marriage as a formal marriage or informal union occurring before the age of 18. More than 650 million living women were married before the age of 18 globally, and 12 million women are married as children each year, with about half of those occurring in Bangladesh, Brazil, Ethiopia, India and Nigeria.[1] More than 40%, or 285 million, women who married before the age of 18 live in South Asia.

The threshold of 18 years of age is defined in several conventions, treaties, and international agreements, including the Convention on the Rights of the Child (ICRC), the Convention on the Elimination of All forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), as well as resolutions of the UN Human Rights Council. The ICRC emphasizes full and informed consent for marriage while recognizing that children do not have that maturity, information or agency to give such consent. UDHR states that consent cannot be free and full when one of the parties involved is not sufficiently mature to make an informed decision about a life partner. Globally, the average legal age of marriage is 17 for boys and 16 for girls, but many countries permit them, particularly for girls, to marry much younger[2]. The average age of consent in European countries[3] is 16 years old, with the lowest age of consent in Estonia at 15 years old. In the USA the minimum age of martial consent is 12 years old with the parents’ permission in some states, while sexual consent is between 16 and 18 years old, also depending on the state. The USA is not signatory to the ICCR, either.

As per UNICEF South Asia has the highest rates of child marriage in the world.[4] Almost half (45%) of all women aged 20-24 years reported being married before the age of 18. Almost one in five girls (17%) are married before the age of 15.

As per UNICEF South Asia has the highest rates of child marriage in the world.[4] Almost half (45%) of all women aged 20-24 years reported being married before the age of 18. Almost one in five girls (17%) are married before the age of 15.Child marriage is declining but is unable to keep pace with prevalent percentages for population growth. In the South Asian Association for Regional Co-operation (SAARC) countries, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Afghanistan and Nepal have legally set the marriageable and age of consent at 16 years. While, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives[5] have set it at 18 years. The age of consent for marriage is defined in criminal law in most of the SAARC countries. Pakistan stands at the second lowest age in SAARC.

The SAARC’s Kathmandu call for action in 2014[6] impressed upon member states to:

Acknowledge that child marriage is not merely a social evil but a punishable crime and a human rights violation which triggers a continuum of harms that have a long-term detrimental impact on the lives of girls and women, not just at an individual level but also with regard to countries’ overall socio-economic development and prosperity. Violence against children, especially girls married as children, is not solely a private family matter but a public concern that casts upon States the obligation of due diligence to investigate cases of child marriage, prosecute perpetrators, provide redress to victim.

UNICEF informs that 10 million additional girls are at risk of child marriage due to Covid-19.[7] Pandemic-related mobility restrictions are making it difficult for girls to access the health care, education and social services that can protect them from child marriage, unwanted pregnancy and/or Gender-Based Violence (GBV). Closure of schools is and will contribute to higher school dropout rates for girls, with lower chances of return. Poverty is core driver of child marriage both globally and in Pakistan. The economic impact of Covid-19 (both income and food insecurity) will deepen the impact of poverty that will lead to parents marry their underage daughters to ease financial burdens.

In the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Goal-5 (Target 5.3) compels nations to commit to eliminating “child, early and forced marriages” by 2030, which has been co-opted by Pakistan under an act in parliament. Target 5.3 measures child marriage at two levels i.e. at 15 and 18 years old. Married women in the age cohort of 20-24 years are asked their age of marriage to generate this data, via the Pakistan Demography and Health Survey (PDHS) 2017-2018. Table 4.3 of the PDHS 2017-18 shows that in Pakistan, 3.6% of girls get married under the age of 15 years; and 18.3% girls get married under the age of 18 years

There are many drivers, or factors of child marriage. These are categorized at a social, economic, institutional, legal and policy level. They collectively impact the socio-economic status of an individual and family to result in child marriage. These drivers operate at the state, community, family and individual level and are highly contingent upon local context.

Age and consent are critical to child marriage, which are dependent on birth registration, marriage documentation and above all legal definition of being a child. Under the legal rubric, determination of age is found in different statutes which are not complimentary and allows a girl to be married at 16 years of age; whereas for boys it set the age limit at 18.[8] Education is globally recognized to be a protective factor to stop child marriage, which is demonstrable in Pakistan as well. There is a steady upward gradation in median age at first marriage for women, from 18.7 years for those with no education to 19.8 years for those with primary school education, 22.2 years old for those with secondary education and 24.9 years old for those with higher education.

Pakistan is a patriarchal society with varying degrees of independence for women, as per their socio-economic class and education. The family and clan remain a strong unit of social reference and standing. Parents are primary care givers and financial supporters for children (even after they are of legal age), and hold a socio-religio-accepted position to be the decision maker for their children, including in marriage. A gradual trend of shared decision-making is being recorded for the middle class, but for the upper class and poor it remains unchanged. Poverty, patriarchal structures, harmful socio-customary practices, and economic interest relegate women and the girl child to a low status. Religion as a frame of reference governs aspects of everyday life and behaviour patterns. Quite often, this framing is religio-legitimizing and prevailing customs and traditions are imposed as a means of controlling social narratives, specifically around early and child marriage.

The persistence of child marriage has long-term implications on the life cycle of a girl child, staring with access to basic human needs, the foundation of well-being and opportunities. Girls who marry in childhood face immediate to lifelong consequences. At the outset it usurps their agency and control of their own life. In most cases it takes them out of school and costs them access to education, which has future implications of being able to achieve gainful employment. Families – under religious, cultural or social practices – takeover their consent.

The vulnerability of orphans and stepchildren to child marriage has been reported as high, especially in disaster and conflict areas. Step-daughters and orphan girls are more likely to be married at early ages. At the community level, extended families are involved in the care of orphans and meeting their basic needs through early and middle childhood

Respondents in one study asserted that when orphans reach puberty, guardians may think that their duty of care has been met and that it is acceptable to seek out marriage for non-biological children in the house. [9] Orphans and step children are widely cited as being mistreated or discriminated against. Such treatment renders marriage a more attractive option for girls because they may attempt to run away from what they deem an intolerable living situation.

The health consequences of child marriage are the gravest. Child marriage increases the risk of early and unplanned pregnancy, causing inter-generational health impacts i.e. risk of maternal complications and mortality. With such weak agency and stature, girls in child marriages are more likely to experience domestic violence. Overall, it isolates girls from family and friends and excludes them from participating in their communities, taking a heavy toll on their mental health and well-being.

This policy explainer is derived from United Nations Population Fund (@UNFPAPakistan), population council Pakistan's publications and input from Ms. @shiringul