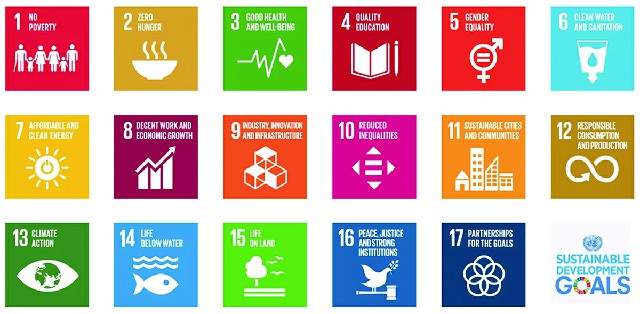

In 2018, the Government of Punjab took a principle decision to include around 38 of the 244 SDG indicators in the ‘Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS)’. The decision was made to facilitate the critical yet cumbersome process of creating SDG baselines that could enable the government to set the SDG targets for 2030. Some of these 38 indicators were already part of MICS while some new variables were added against which questionnaires were designed, a sample was developed and data collection timelines and modalities were fixed. MICS is a flagship product of the Bureau of Statistics Punjab and is meant to provide data support and evidence to the design and formulation of public policy in the province.

For those working on the mainstreaming and localization of the SDGs in Punjab, the setting up of 38 baselines was a huge milestone. Not only were they able to set baselines against 38 of the 244 indicators but also without a direct cost to the SDGs unit set up in the province. To many who worked in the SDGs unit in Punjab, the 38 baselines were a privilege, much like a luxury – since, as it happened, SDG mainstreaming and localization plans, policies and targets, even in respect of other indicators, were derived from and determined under the influence of the 38 available baselines. In the more developed parts of the world, baselining was not a critical activity because most of the data that the SDGs required was already collected either by some governmental statistical agency or by a think tank/research institute working in that sector. In the developed world, policymakers only had to assess state capacity to add it to the current baselines to obtain futuristic targets.

Since early 2016 when Pakistan adopted the SDGs as its national development agenda, it has been struggling with establishing credible baselines and on the basis of those, attainable and realistic targets. Many think that we have begun to make focused progress toward the SDGs but the reality is that we are yet to extricate ourselves from the clutches of data poverty – a problem that has disabled the formation of baselines and targets that can tell the government what it needs to do, by much how much and in what direction. Many delivery units like the Prime Minister’s Performance Delivery Unit (PMDU) and the units set up to improve service delivery in provincial departments and federal ministries cannot direct financial investments and human and technical resources towards the most appropriate and contextually correct policies and plan – simply because they do not have the luxury of data that is both relevant and complete.

Poverty is a multi-dimensional phenomenon. Economists and social scientists have tried to disaggregate disadvantages across a wide range of economic and social criteria to estimate health, education, income and various other types of poverty. The other exercise that they have conducted is to build consensus upon the income, health and education thresholds (poverty lines) beneath which a certain person/household could be considered marginally or terminally poor, thereby requiring the assistance of governments and donors in the developing world. Depending on the pervasiveness and intensity of the incidence of poverty, governments design poverty alleviation strategies and programs, most notably cash transfer and food stamp programs that have emerged and gained immense coinage in the last few decades.

Pakistan’s Ehsas and Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP) are good examples of how cash transfers are designed and the extent to which they can or cannot be effective in undoing the impacts of poverty. While one can go to lengths in discussing what are the most suitable criteria to estimate poverty and what strategies states and international development/financial organizations should adopt to defeat poverty, in a rapidly globalizing world, as renowned Pakistani economist Shahid Javed Burki calls it, greater emphasis has to be laid on understanding the nexus and linkages between technology and policy. That is the need to integrate policy – including its implementation modalities – with technology, most specifically data.

There are countries that do this well. And there are countries that struggle with the making and implementing of public policies because their data architecture is poor. They are, as I call it, the ‘data poor’ countries.

Data poverty, like other forms of poverty, is also a multi-dimensional phenomenon. Some countries are data poor because their data is not credible, as the methods used to collect data are outdated, non-technical and incongruent with some international standards. Non-standardization of data collection methods and techniques, amongst other corrupt practices of data collection, is one primary reason why a lot of data collected in the developing world does not have much acceptability within international development and financial institutions. That has led institutions like World Bank and IMF to pioneer their own data sets that have since become more popular sources of data on developing countries, compared to data produced by their own government-run statistical institutions.

Other forms of data poverty include irrelevance and conjectures. The data collected in such cases is irrelevant to policy and program areas where data is most critically required – and is more in line with areas where governments can function with non-data inputs. For data that is available and relevant, disaggregations and deep statistics are not available. For many SDG indicators, data for females is absent. There are also rural-urban divides. For effective policy and program design and implementation, aggregated data holds lesser significance than disaggregated data.

The north-south divide between the developed and developing world – something that was picked up by many development models including one on core and periphery countries – was initially challenged by the rise of East Asia, most specifically of China, that not only grew at 10% per annum on average between 1970 and 2000 but also managed to disturb the global economic hierarchy by challenging the economic superiority of the Western economic powers. However, with the exception of East Asia, the north-south divide remained relevant in respect of most countries in the south that still remained subservient to and dependent upon the advanced, industrialized and developed countries of the north.

What should instead challenge the north-south divide today is the basis upon which such a divide is seen. Whether it ought to be based on one predominant form of poverty or another is the question that continues to separate policymakers. Clearly, if $1.25/day is used as an international poverty line, many of the world’s poor would seem to live in some countries and few regions of the world. Most of those countries and regions would undeniably lie in the southern hemisphere. However, if the poverty configuration is reoriented towards ‘data poverty’, the north-south divide may have to be readjusted to include some countries of the global north that don’t do so well in terms of collecting, analyzing and using data for policy. A different possibility could see the north-south divide being strongly reinforced.

In either case, what needs to be understood is that many of the other forms of poverty depend upon disadvantages and lack of data which is a critical input for programmes and policies that can be instrumental in alleviating poverty. And hence, the global divide that policy-makers must now begin to focus upon is that between data-rich and data-poor countries, it will be difficult to attribute a ‘poverty line’ to this form of poverty. But its alleviation – with a little focus on the capacity and direction of statistical arms of the governments – can be much easier to achieve.

For those working on the mainstreaming and localization of the SDGs in Punjab, the setting up of 38 baselines was a huge milestone. Not only were they able to set baselines against 38 of the 244 indicators but also without a direct cost to the SDGs unit set up in the province. To many who worked in the SDGs unit in Punjab, the 38 baselines were a privilege, much like a luxury – since, as it happened, SDG mainstreaming and localization plans, policies and targets, even in respect of other indicators, were derived from and determined under the influence of the 38 available baselines. In the more developed parts of the world, baselining was not a critical activity because most of the data that the SDGs required was already collected either by some governmental statistical agency or by a think tank/research institute working in that sector. In the developed world, policymakers only had to assess state capacity to add it to the current baselines to obtain futuristic targets.

Since early 2016 when Pakistan adopted the SDGs as its national development agenda, it has been struggling with establishing credible baselines and on the basis of those, attainable and realistic targets. Many think that we have begun to make focused progress toward the SDGs but the reality is that we are yet to extricate ourselves from the clutches of data poverty – a problem that has disabled the formation of baselines and targets that can tell the government what it needs to do, by much how much and in what direction. Many delivery units like the Prime Minister’s Performance Delivery Unit (PMDU) and the units set up to improve service delivery in provincial departments and federal ministries cannot direct financial investments and human and technical resources towards the most appropriate and contextually correct policies and plan – simply because they do not have the luxury of data that is both relevant and complete.

Since early 2016 when Pakistan adopted the SDGs as its national development agenda, it has been struggling with establishing credible baselines and on the basis of those, attainable and realistic targets

Poverty is a multi-dimensional phenomenon. Economists and social scientists have tried to disaggregate disadvantages across a wide range of economic and social criteria to estimate health, education, income and various other types of poverty. The other exercise that they have conducted is to build consensus upon the income, health and education thresholds (poverty lines) beneath which a certain person/household could be considered marginally or terminally poor, thereby requiring the assistance of governments and donors in the developing world. Depending on the pervasiveness and intensity of the incidence of poverty, governments design poverty alleviation strategies and programs, most notably cash transfer and food stamp programs that have emerged and gained immense coinage in the last few decades.

Pakistan’s Ehsas and Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP) are good examples of how cash transfers are designed and the extent to which they can or cannot be effective in undoing the impacts of poverty. While one can go to lengths in discussing what are the most suitable criteria to estimate poverty and what strategies states and international development/financial organizations should adopt to defeat poverty, in a rapidly globalizing world, as renowned Pakistani economist Shahid Javed Burki calls it, greater emphasis has to be laid on understanding the nexus and linkages between technology and policy. That is the need to integrate policy – including its implementation modalities – with technology, most specifically data.

There are countries that do this well. And there are countries that struggle with the making and implementing of public policies because their data architecture is poor. They are, as I call it, the ‘data poor’ countries.

Many of the other forms of poverty depend upon disadvantages and lack of data which is a critical input for programmes and policies that can be instrumental in alleviating poverty

Data poverty, like other forms of poverty, is also a multi-dimensional phenomenon. Some countries are data poor because their data is not credible, as the methods used to collect data are outdated, non-technical and incongruent with some international standards. Non-standardization of data collection methods and techniques, amongst other corrupt practices of data collection, is one primary reason why a lot of data collected in the developing world does not have much acceptability within international development and financial institutions. That has led institutions like World Bank and IMF to pioneer their own data sets that have since become more popular sources of data on developing countries, compared to data produced by their own government-run statistical institutions.

Other forms of data poverty include irrelevance and conjectures. The data collected in such cases is irrelevant to policy and program areas where data is most critically required – and is more in line with areas where governments can function with non-data inputs. For data that is available and relevant, disaggregations and deep statistics are not available. For many SDG indicators, data for females is absent. There are also rural-urban divides. For effective policy and program design and implementation, aggregated data holds lesser significance than disaggregated data.

The north-south divide between the developed and developing world – something that was picked up by many development models including one on core and periphery countries – was initially challenged by the rise of East Asia, most specifically of China, that not only grew at 10% per annum on average between 1970 and 2000 but also managed to disturb the global economic hierarchy by challenging the economic superiority of the Western economic powers. However, with the exception of East Asia, the north-south divide remained relevant in respect of most countries in the south that still remained subservient to and dependent upon the advanced, industrialized and developed countries of the north.

What should instead challenge the north-south divide today is the basis upon which such a divide is seen. Whether it ought to be based on one predominant form of poverty or another is the question that continues to separate policymakers. Clearly, if $1.25/day is used as an international poverty line, many of the world’s poor would seem to live in some countries and few regions of the world. Most of those countries and regions would undeniably lie in the southern hemisphere. However, if the poverty configuration is reoriented towards ‘data poverty’, the north-south divide may have to be readjusted to include some countries of the global north that don’t do so well in terms of collecting, analyzing and using data for policy. A different possibility could see the north-south divide being strongly reinforced.

In either case, what needs to be understood is that many of the other forms of poverty depend upon disadvantages and lack of data which is a critical input for programmes and policies that can be instrumental in alleviating poverty. And hence, the global divide that policy-makers must now begin to focus upon is that between data-rich and data-poor countries, it will be difficult to attribute a ‘poverty line’ to this form of poverty. But its alleviation – with a little focus on the capacity and direction of statistical arms of the governments – can be much easier to achieve.