Fifty-seven years ago, in the second year of his presidency, John F. Kennedy wrote in a widely known American magazine, American Heritage, “history, after all, is the memory of a nation... the means by which a nation establishes its sense of identity and purpose.” John Dos Passos, a leading American novelist of the 1920s and 1930s and a prominent public intellectual, who like many others started politically on the left and ended on the right, went further; in his book The Ground We Stand On, he wrote, “when there is a quicksand of fear under men’s reasoning, a sense of continuity with generations gone before can stretch like a lifeline across the scary present.”

And yet, as we watch the current shenanigans in US politics, we see an enactment of the more cynical assessment of the great British novelist Aldous Huxley, “that men do not learn very much from the lessons of history is the most important of all the lessons of history.” The Trump administration continues to govern shambolically, to make policy decisions (such as the withdrawal from the Paris Climate Accord) apparently out of spite rather that any intellectual process of factual examination. It creeps closer to serious internal crisis over its suspected pre-election relationship with Russian intelligence.

Not only was the Paris decision probably the tipping point for its relationships with America’s closest allies, but likely the slipping point for its remaining coherence. Advisors have left, and the press is reporting that it cannot find replacements for departing White House officials. Those who know them are wondering how long the remaining so-called “adults in the room,” referring especially to Secretary of Defense James Mattis, will remain in the room. Mattis must be seething at the insulting rebuke President Trump aimed at the NATO heads of state in Brussels last week as it undercut the assurances of our undying support he and others US national security officials have given those leaders. One wonders how they can work for a President who keeps undoing what they have laboured so strenuously to do—to bind up the NATO alliance which is (was?) the centre of our national security strategy; to keep the pressure on Russia and its threat to the alliance; to find a workable approach to the Middle East mess.

To all appearances, the nationalist, populist, nativist element among the President’s advisors, the America Firsters, have regained the top rung in his ladder of advisors. Clearly it was that faction which wrote the speech he made to NATO leaders, and that won the battle that is said to have gone on over the Paris Climate Agreement. There are reports that seek to soothe us that the NATO performance and the decision to withdraw from the Paris Accord do not necessarily mean that the President is now under the influence of the America First faction. It is said that he listens to all sides and then makes decisions on his own. But I find that just as alarming as him being under their influence. After all, he did take the America First side on two of his most important decisions as to America’s international relations and its national security strategy. But even more problematic is his that decision process remains not only erratic and compulsive, but based on alternative facts, i.e. lies. This was evident in his NATO remarks and in his explanation of why he decided to withdraw from the Paris Accord.

General Mattis is a good segue in this narrative. I assume that like others in his circle of advisors who appear serious and fact-oriented, he is motivated by patriotism—colleagues who know him swear as to his honesty and probity. But I wonder—and he must wonder too—how it is possible to help his country by serving a President so devoted to untruth, one who, as Angela Merkel said of Vladimir Putin, is living in an alternative universe. But at least General Mattis is motivated by patriotism. Many of the others around the President are motivated by ideology, an ideology of two kinds; either they buy into the America First ideology, or into an ideology of self-aggrandizement. The White House seems littered with both kinds.

It is the members of Congress, however, who are the largest embarrassment. On the Republican side, whether Tea Party, moderate, or so-called mainstream conservatives, one strong principle of conservatism generally should be to preserve the Republic. Yet they have discarded that principle for the sake of pragmatism to achieve a conservative agenda on the coattails of a President who certainly cares little about the Republic. Many believed, I suspect, that the party and the institutions of government would constrain him. They were wrong because they put the conservative agenda above principle. Now they find that their agenda is in shreds anyway because of the disarray of the Trump administration and its discretions, which are the subject of a serious FBI investigation and may lead to charges against it and a possible constitutional crisis. The Democrats are not much better. Both parties operate like tribal fiefdoms.

A few weeks ago we saw how memory takes nations in different directions. The smashing victory of Emmanuel Macron over Marine Le Pen stands in stark contrast to the election of Donald Trump in the US. Macron, a centrist running on republican principles of democracy and fairness and equality, not only turned back Le Pen, running on a populist, nationalist, nativist platform similar to Trump’s, but he did so resoundingly. In other words, the French remembered their deepest republican principles—democracy, liberty, equality—while the Americans, who have often been described as serial amnesiacs, and in the case of Trump especially the conservatives, did not remember theirs.

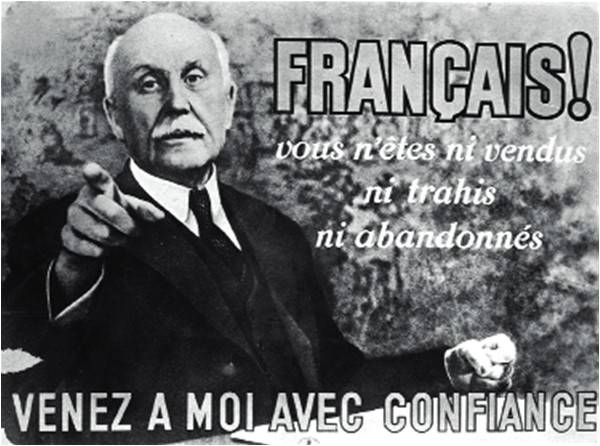

Why? History is the answer. The history of Europe since Roman times is a history of struggle and strife, a history of tragedy. This is embedded in European minds much more strongly that in American ones. And in France, the history of WW2 is particularly acute as France was torn apart after the quick and humiliating defeat when Marshal Pétain, the very conservative, possibly pro-Nazi, and probably partially senile President created the collaborationist Vichy regime to “work with” the Nazi occupation forces. After 77 years, the stigma is still remembered, and the memory is still sharp. French conservatives and centrists especially remember because many of their fathers and grandfathers followed the orders of the Marshal, and came to realize that you can’t really collaborate with a criminal regime without becoming a criminal. French drama still portrays the dilemma that those trying to collaborate and yet avoid criminality could not do so, and that dishonour accompanied collaboration. De Gaulle, who led the resistance, was in fact from the far right, but he grasped the difference between patriotism and nationalism. It goes back to the Faust legend—you can’t make a deal with the devil (i.e. evil) and come out clean.

I have written about the Faustian bargains of Pakistan many times before. Vichy is an example of a Faustian bargain on a different scale. But I hear almost every day suggestions that would suggest that one would be possible in the US. When one wishes for impeachment or some other early end to the Trump administration, many friends reply that VP Pence is waiting in the wings with the same retrogressive agenda that Trump has endorsed, so why trade one for the other, particularly as Pence is unlikely to cause havoc that would bring him down too. This is the same Vichy thinking which tore France apart. As much as I abhor it, it is not the agenda that should disqualify Trump, it is his toxic disregard of all the values of democracy on which our political system is based.

The author is a Senior Scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington DC, and a former US diplomat who was Ambassador to Pakistan and Bangladesh

And yet, as we watch the current shenanigans in US politics, we see an enactment of the more cynical assessment of the great British novelist Aldous Huxley, “that men do not learn very much from the lessons of history is the most important of all the lessons of history.” The Trump administration continues to govern shambolically, to make policy decisions (such as the withdrawal from the Paris Climate Accord) apparently out of spite rather that any intellectual process of factual examination. It creeps closer to serious internal crisis over its suspected pre-election relationship with Russian intelligence.

Not only was the Paris decision probably the tipping point for its relationships with America’s closest allies, but likely the slipping point for its remaining coherence. Advisors have left, and the press is reporting that it cannot find replacements for departing White House officials. Those who know them are wondering how long the remaining so-called “adults in the room,” referring especially to Secretary of Defense James Mattis, will remain in the room. Mattis must be seething at the insulting rebuke President Trump aimed at the NATO heads of state in Brussels last week as it undercut the assurances of our undying support he and others US national security officials have given those leaders. One wonders how they can work for a President who keeps undoing what they have laboured so strenuously to do—to bind up the NATO alliance which is (was?) the centre of our national security strategy; to keep the pressure on Russia and its threat to the alliance; to find a workable approach to the Middle East mess.

A few weeks ago we saw how memory takes nations in different directions. The smashing victory of Emmanuel Macron over Marine Le Pen stands in stark contrast to the election of Donald Trump in the US. Macron, a centrist running on republican principles of democracy and fairness and equality, not only turned back Le Pen, running on a populist, nationalist, nativist platform similar to Trump's, but he did so resoundingly

To all appearances, the nationalist, populist, nativist element among the President’s advisors, the America Firsters, have regained the top rung in his ladder of advisors. Clearly it was that faction which wrote the speech he made to NATO leaders, and that won the battle that is said to have gone on over the Paris Climate Agreement. There are reports that seek to soothe us that the NATO performance and the decision to withdraw from the Paris Accord do not necessarily mean that the President is now under the influence of the America First faction. It is said that he listens to all sides and then makes decisions on his own. But I find that just as alarming as him being under their influence. After all, he did take the America First side on two of his most important decisions as to America’s international relations and its national security strategy. But even more problematic is his that decision process remains not only erratic and compulsive, but based on alternative facts, i.e. lies. This was evident in his NATO remarks and in his explanation of why he decided to withdraw from the Paris Accord.

General Mattis is a good segue in this narrative. I assume that like others in his circle of advisors who appear serious and fact-oriented, he is motivated by patriotism—colleagues who know him swear as to his honesty and probity. But I wonder—and he must wonder too—how it is possible to help his country by serving a President so devoted to untruth, one who, as Angela Merkel said of Vladimir Putin, is living in an alternative universe. But at least General Mattis is motivated by patriotism. Many of the others around the President are motivated by ideology, an ideology of two kinds; either they buy into the America First ideology, or into an ideology of self-aggrandizement. The White House seems littered with both kinds.

It is the members of Congress, however, who are the largest embarrassment. On the Republican side, whether Tea Party, moderate, or so-called mainstream conservatives, one strong principle of conservatism generally should be to preserve the Republic. Yet they have discarded that principle for the sake of pragmatism to achieve a conservative agenda on the coattails of a President who certainly cares little about the Republic. Many believed, I suspect, that the party and the institutions of government would constrain him. They were wrong because they put the conservative agenda above principle. Now they find that their agenda is in shreds anyway because of the disarray of the Trump administration and its discretions, which are the subject of a serious FBI investigation and may lead to charges against it and a possible constitutional crisis. The Democrats are not much better. Both parties operate like tribal fiefdoms.

A few weeks ago we saw how memory takes nations in different directions. The smashing victory of Emmanuel Macron over Marine Le Pen stands in stark contrast to the election of Donald Trump in the US. Macron, a centrist running on republican principles of democracy and fairness and equality, not only turned back Le Pen, running on a populist, nationalist, nativist platform similar to Trump’s, but he did so resoundingly. In other words, the French remembered their deepest republican principles—democracy, liberty, equality—while the Americans, who have often been described as serial amnesiacs, and in the case of Trump especially the conservatives, did not remember theirs.

Why? History is the answer. The history of Europe since Roman times is a history of struggle and strife, a history of tragedy. This is embedded in European minds much more strongly that in American ones. And in France, the history of WW2 is particularly acute as France was torn apart after the quick and humiliating defeat when Marshal Pétain, the very conservative, possibly pro-Nazi, and probably partially senile President created the collaborationist Vichy regime to “work with” the Nazi occupation forces. After 77 years, the stigma is still remembered, and the memory is still sharp. French conservatives and centrists especially remember because many of their fathers and grandfathers followed the orders of the Marshal, and came to realize that you can’t really collaborate with a criminal regime without becoming a criminal. French drama still portrays the dilemma that those trying to collaborate and yet avoid criminality could not do so, and that dishonour accompanied collaboration. De Gaulle, who led the resistance, was in fact from the far right, but he grasped the difference between patriotism and nationalism. It goes back to the Faust legend—you can’t make a deal with the devil (i.e. evil) and come out clean.

I have written about the Faustian bargains of Pakistan many times before. Vichy is an example of a Faustian bargain on a different scale. But I hear almost every day suggestions that would suggest that one would be possible in the US. When one wishes for impeachment or some other early end to the Trump administration, many friends reply that VP Pence is waiting in the wings with the same retrogressive agenda that Trump has endorsed, so why trade one for the other, particularly as Pence is unlikely to cause havoc that would bring him down too. This is the same Vichy thinking which tore France apart. As much as I abhor it, it is not the agenda that should disqualify Trump, it is his toxic disregard of all the values of democracy on which our political system is based.

The author is a Senior Scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington DC, and a former US diplomat who was Ambassador to Pakistan and Bangladesh