The residents of district Malir, in Karachi, have been protesting the demolition of the Sayad Hashmi Reference Library for the construction of the Malir Expressway. This issue directly pertains to the laws and policies related to preserving and protecting cultural heritage.

International cultural heritage law is very important in today’s polarised age, where inclusivity and diversity are recognised but not always accepted. This body of law distinguishes between ‘cultural property’ and ‘cultural heritage,’ the latter of which deals with the identities of groups and communities. These identities can be tangible, like monuments and paintings, or intangible, like languages, religious beliefs, or fashion.

The death of this cultural heritage would amount to a great loss. In particular, the Baloch roots of Karachi could end up disappearing forever

The term ‘cultural property’ first appeared in the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict. Subsequently, it was used by the 1970 UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export, and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, also known as the 1970 UNESCO Convention. The Second Protocol to the Hague Convention of 1954 applies to both international and non-international armed conflicts and adopts a similar approach.

Following this, the 1995 UNIDROIT Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects was introduced. This convention aimed to address the achievements and successes of the 1970 UNESCO Convention while incorporating the lessons learned and the transformation in the attitudes of states during this period. States were rethinking their positions on this issue and were increasingly ready and willing to cooperate.

Lastly, the 2005 Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions in Paris defines ‘cultural diversity,’ ‘cultural content,’ and ‘cultural expressions.’

Even under customary international humanitarian law, the destruction, pillage, looting, or confiscation of works of art and other items of public or private property during armed conflict is forbidden. These prohibitions are incorporated in the Hague Convention respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land, adopted by the First Peace Conference in 1899 and revised in the Second Peace Conference in 1907, as well as in the 1907 Hague Convention concerning Bombardment by Naval Forces in Time of War.

The concept of cultural heritage has a wider scope and even impacts the concept of cultural property, allowing them to be attributed to the group by whom they were created or where the community is located, or even to the entirety of humanity.

The ongoing conflict in Gaza is witnessing a cultural genocide that has indiscriminately destroyed tangible heritage like museums, churches, and mosques, as well as intangible heritage such as customs, culture, and artifacts. This includes the Union of Palestinian Artists on Jalaa Street in Gaza City and the famous clay pots in the city’s al-Fawakhir district.

In fact, the term genocide was derived from cultural genocide, described by Polish lawyer Raphael Lemkin in 1944. In the same work, he coined the term genocide. Thus, it is impossible to separate genocide from cultural genocide, and the relationship between genocide and the protection of cultural heritage and identity is crucially interlinked and cannot be parted.

Pakistan joined UNESCO on the 14th September 1949 and has a National Heritage and Culture Division. Article 28 of the 1973 Constitution of Pakistan deals with the preservation of language, script, and culture and recognises it as a fundamental right. In 1947, Pakistan adopted the Ancient Monument Preservation Act 1904, which was later repealed and replaced by the Antiquities Act 1968 and the Antiquities Ordinance 1975, which were then repealed by the Antiquities Act 1975.

However, with so many laws, there are doubts on how much Pakistan truly prioritises preserving its heritage. In 2017, the Supreme Court of Pakistan set aside the decision of the Lahore High Court, to halt construction of the Orange Line Metro Train, within 200 feet of 11 heritage sites in Lahore.

In 2023, the over-150-year-old Mari Mata Hindu temple was demolished in Soldier Bazaar, Karachi, during the night hours. The persecution of the Hindu community of Sindh is not a secret and failure of the government to protect them and their heritage only paints a poor picture of what is going on in Malir.

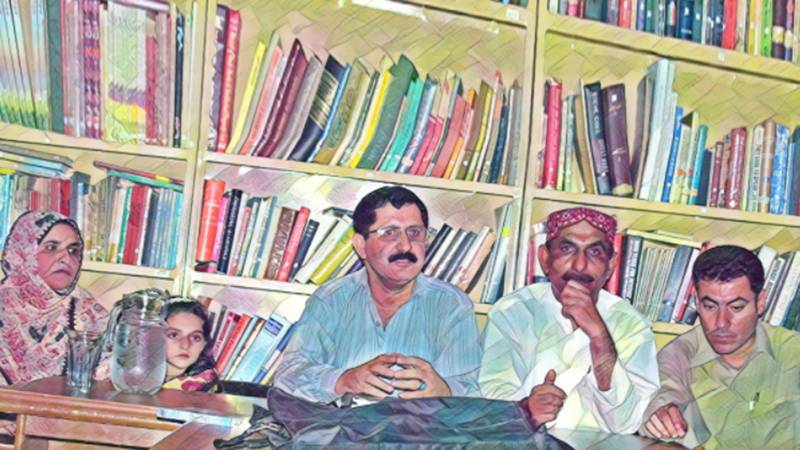

The residents of Malir are protesting to protect the Sayad Hashmi Reference Library in Malir, for its vast and valuable collection of books pertaining to Balochi language, history and heritage. It was named after a great Baloch scholar Sayad Zahoor Shah Hashmi (1926-1978). Zubeida Mustafa, a veteran journalist, knows its importance, however, it would seem that government, legislature and even the judiciary would not or could not do anything to save the library. The president of the library and the Chairman of the Department of Persian at the University of Karachi Dr Ramzan Bamri has pointed out that the library was not present in the original map of the Malir Expressway, and although he might be able to make his case under international and domestic laws, he would not be able to save it – which he knows very well.

The death of this cultural heritage would amount to a great loss. In particular, the Baloch roots of Karachi could end up disappearing forever.