The writing on the wall after the July 8 killing of 22-year-old popular militant leader Burhan Wani had become obvious for all the stakeholders of Indian-Administered Kashmir. As angry Kashmiris poured out in to the streets for their right to self-determination, the Indian government reacted—killing scores of them and blinding hundreds with pellet guns.

As soon as the protests engulfed the entire region, Pakistan too was faced with a riddle: How should it deal with a rival that is bigger in size, richer in wealth and oceans ahead in influence over the international community?

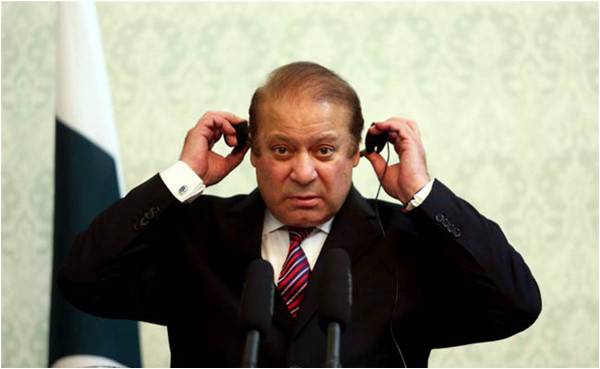

Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif knew it would be an uphill task to persuade the international community to dissuade India from continuing atrocities against Kashmiris and agreeing on a resolution. “Pakistan’s weight is far less than it should be in the international domain as compared to India’s,” explains former ambassador Sarwar Naqvi. The international community is conscious about taking up the Kashmir issue but they do not wish to take a clear stand on India. “I don’t think our diplomatic sense could make a difference on Kashmir but the latest situation in Kashmir has provided us an opportunity. Pakistan can bank on the indigenous Kashmir freedom movement by telling the world about it.”

The prime minister knows that years of diplomacy have not borne fruit and that the international community has turned a blind eye to several pleas to find a solution. This realisation pushed him to convene a diplomats’ conference in Islamabad and write a letter to UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon. In response, the UN secretary-general said the atrocities in India should stop and India and Pakistan should talk. He did not, however, mention the Kashmiri right to self-determination even though the UN passed a resolution on it decades ago. “Kofi Annan, as secretary-general of the UN, had stated some eight years back when he visited Pakistan that the resolutions on Kashmir had become obsolete,” says Shahid Amin, a senior former diplomat. He feels India is not going to change its stance on Kashmir but Pakistan should not waver, and highlight the atrocities in the world to compel it to pressure India.

The latest in the series of “out-of-the-box” attempts to highlight the Kashmir cause was the premier’s decision to send 22 parliamentarians as envoys to the most important world capitals. The 22 parliamentarians include Ijazul Haq and Malik Uzair for Belgium, Khusro Bakhtiar and Alamdad Laleka for China, Raza Hayat Hiraj, Junair Anwar Chaudhry and Nawaz Ali Wassan for Russia. Maulana Fazlur Rehman, Maj. (Retd) Tahir Iqbal and Muhammad Afzal Khokhar will visit Saudi Arabia. Mohsin Shahnawaz Ranjha and Malik Pervaiz will go to Turkey. Lt Gen. (retd) Abdul Qayyum and Qaiser Sheikh will go to Britain. Mushahid Hussain Syed and Shazra Mansab Ali Khan would highlight the Kashmir cause in the US and the UN in New York, Ayesha Raza Farooq and Rana Muhammad Afzal in France, Awais Leghari and at the United Nations (Geneva) and Abdul Rehman Kanju in South Africa.

India has reacted sharply to this decision and warned Pakistan against what it called interference in its affairs. “Pakistan should not internationalise this [Kashmir] because it is a bilateral issue,” Indian Minister of State for External Affairs MJ Akbar told the media. “It is Pakistan’s individual right if it wants its MPs to go for free tourism.”

Nawaz Sharif’s decision did not go down well at home either, with the opposition or with independent observers. Pakistan Peoples Party’s Bilawal Bhutto Zardari tweeted: “Our PM’s solution to Kashmir. Send cronies and allies on state-sponsored holidays.” Journalist Zahid Hussain calls it a joke. “Pakistan has never faced such great diplomatic challenges before. The first thing to do is appoint a foreign minister to effectively highlight the atrocities in Kashmir.”

Diplomats say this is not the first time that Pakistan has tried to shoehorn a politician into a diplomat’s position. Asking not to be identified a diplomat said that when this happens all they can do is “receive them, brief them and even schedule their meeting with important officials.” Indeed, PML-N MNA Qaiser Ahmed Sheikh, headed to the UK, said: “So far the government has not told us anything about the schedule of our visit.” When asked if he knew who he would meet and the parameters of his interaction, he said: “I could not say anything unless the foreign office briefs me on the subject.” He said Adviser to the Prime Minister on Foreign Affairs Sartaj Aziz would be doing that.

Several experts believe that successive governments in Pakistan have damaged the Kashmir cause by abandoning the principled stance that hinges on the UN resolution on the right to self-determination for Kashmiris. They feel India has not only contributed to but benefitted from these deviations on policy.

Take for instance the that that on numerous occasions Indian-Administered Kashmir was cast aside from the list of issues needing talks between India and Pakistan. The exclusion of the word Kashmir from the joint statement issued after talks between Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif in the Russian city of Ufa on July 10, 2015, is a glaring example. On several occasions, Pakistani diplomats have agreed to skip talks on “occupied Kashmir” when their Indian counterparts first sought developments on the status of what we call “Azad Jammu and Kashmir”.

India’s push to talk on terrorism alone—which resulted in talks between the national security advisers in New Delhi sans Kashmir—signals a sophisticated maneuver to keep Pakistan from talking on Kashmir. Modi’s government has led from the front in diminishing Pakistan’s say as is evident from the suspension of talks in the wake of Pakistan’s High Commissioner Dr Abdul Basit invitation to Kashmiri leaders. Modi has built the foundation of this policy on the premise that Pakistan allows its soil to perpetuate terror not only in India but Afghanistan too. These wily Indian moves bring into sharp focus not only Pakistan’s poor Kashmir policy but its fractured ties with immediate neighbours.

“Unfortunately, Pakistan’s foreign policy is not being made where it should be,” says Pakistan’s former High Commissioner to India Ashraf Jehangir Qazi. He believes Pakistan’s Kashmir policy has always been hostage to short-term plans which have been incompatible with the growing geo-strategic and economic importance of India. “What Pakistan needs to do is to formulate a long-term policy on Kashmir that includes mending ties with neighbours, improving law and order, ending human rights abuses—especially in Balochistan—and above all strengthening its feeble economy,” Qazi explains.

The need for an effective policy is not an insignificant subject for the Kashmiris who look to Pakistan for moral, political and ethical support. Hurriyat Conference Chairman Miwaiz Umer Farooq says Kashmiri hearts and minds are with Pakistan and they want Pakistan to internationalise the issue. Talking about Modi’s statement on Balochistan, Mirwaiz said: “India wants to give the impression to its people that the way Pakistan talks about Kashmir they (India) too would point out excesses in Pakistan.”

The quagmire of national politics (Panama Leaks, Altaf Hussain) has kept Pakistan from forming a unified response to India let alone a concrete policy. This is exacerbated by a lack of consultative process among former diplomats and policy-makers on Kashmir.

Faisal Shakeel is an anchor for Current Affairs on Waqt TV and tweets at @sfaisalshakeel

As soon as the protests engulfed the entire region, Pakistan too was faced with a riddle: How should it deal with a rival that is bigger in size, richer in wealth and oceans ahead in influence over the international community?

Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif knew it would be an uphill task to persuade the international community to dissuade India from continuing atrocities against Kashmiris and agreeing on a resolution. “Pakistan’s weight is far less than it should be in the international domain as compared to India’s,” explains former ambassador Sarwar Naqvi. The international community is conscious about taking up the Kashmir issue but they do not wish to take a clear stand on India. “I don’t think our diplomatic sense could make a difference on Kashmir but the latest situation in Kashmir has provided us an opportunity. Pakistan can bank on the indigenous Kashmir freedom movement by telling the world about it.”

The prime minister knows that years of diplomacy have not borne fruit and that the international community has turned a blind eye to several pleas to find a solution. This realisation pushed him to convene a diplomats’ conference in Islamabad and write a letter to UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon. In response, the UN secretary-general said the atrocities in India should stop and India and Pakistan should talk. He did not, however, mention the Kashmiri right to self-determination even though the UN passed a resolution on it decades ago. “Kofi Annan, as secretary-general of the UN, had stated some eight years back when he visited Pakistan that the resolutions on Kashmir had become obsolete,” says Shahid Amin, a senior former diplomat. He feels India is not going to change its stance on Kashmir but Pakistan should not waver, and highlight the atrocities in the world to compel it to pressure India.

The latest in the series of “out-of-the-box” attempts to highlight the Kashmir cause was the premier’s decision to send 22 parliamentarians as envoys to the most important world capitals. The 22 parliamentarians include Ijazul Haq and Malik Uzair for Belgium, Khusro Bakhtiar and Alamdad Laleka for China, Raza Hayat Hiraj, Junair Anwar Chaudhry and Nawaz Ali Wassan for Russia. Maulana Fazlur Rehman, Maj. (Retd) Tahir Iqbal and Muhammad Afzal Khokhar will visit Saudi Arabia. Mohsin Shahnawaz Ranjha and Malik Pervaiz will go to Turkey. Lt Gen. (retd) Abdul Qayyum and Qaiser Sheikh will go to Britain. Mushahid Hussain Syed and Shazra Mansab Ali Khan would highlight the Kashmir cause in the US and the UN in New York, Ayesha Raza Farooq and Rana Muhammad Afzal in France, Awais Leghari and at the United Nations (Geneva) and Abdul Rehman Kanju in South Africa.

India has reacted sharply to this decision and warned Pakistan against what it called interference in its affairs. “Pakistan should not internationalise this [Kashmir] because it is a bilateral issue,” Indian Minister of State for External Affairs MJ Akbar told the media. “It is Pakistan’s individual right if it wants its MPs to go for free tourism.”

Nawaz Sharif’s decision did not go down well at home either, with the opposition or with independent observers. Pakistan Peoples Party’s Bilawal Bhutto Zardari tweeted: “Our PM’s solution to Kashmir. Send cronies and allies on state-sponsored holidays.” Journalist Zahid Hussain calls it a joke. “Pakistan has never faced such great diplomatic challenges before. The first thing to do is appoint a foreign minister to effectively highlight the atrocities in Kashmir.”

Diplomats say this is not the first time that Pakistan has tried to shoehorn a politician into a diplomat’s position. Asking not to be identified a diplomat said that when this happens all they can do is “receive them, brief them and even schedule their meeting with important officials.” Indeed, PML-N MNA Qaiser Ahmed Sheikh, headed to the UK, said: “So far the government has not told us anything about the schedule of our visit.” When asked if he knew who he would meet and the parameters of his interaction, he said: “I could not say anything unless the foreign office briefs me on the subject.” He said Adviser to the Prime Minister on Foreign Affairs Sartaj Aziz would be doing that.

Several experts believe that successive governments in Pakistan have damaged the Kashmir cause by abandoning the principled stance that hinges on the UN resolution on the right to self-determination for Kashmiris. They feel India has not only contributed to but benefitted from these deviations on policy.

Take for instance the that that on numerous occasions Indian-Administered Kashmir was cast aside from the list of issues needing talks between India and Pakistan. The exclusion of the word Kashmir from the joint statement issued after talks between Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif in the Russian city of Ufa on July 10, 2015, is a glaring example. On several occasions, Pakistani diplomats have agreed to skip talks on “occupied Kashmir” when their Indian counterparts first sought developments on the status of what we call “Azad Jammu and Kashmir”.

India’s push to talk on terrorism alone—which resulted in talks between the national security advisers in New Delhi sans Kashmir—signals a sophisticated maneuver to keep Pakistan from talking on Kashmir. Modi’s government has led from the front in diminishing Pakistan’s say as is evident from the suspension of talks in the wake of Pakistan’s High Commissioner Dr Abdul Basit invitation to Kashmiri leaders. Modi has built the foundation of this policy on the premise that Pakistan allows its soil to perpetuate terror not only in India but Afghanistan too. These wily Indian moves bring into sharp focus not only Pakistan’s poor Kashmir policy but its fractured ties with immediate neighbours.

“Unfortunately, Pakistan’s foreign policy is not being made where it should be,” says Pakistan’s former High Commissioner to India Ashraf Jehangir Qazi. He believes Pakistan’s Kashmir policy has always been hostage to short-term plans which have been incompatible with the growing geo-strategic and economic importance of India. “What Pakistan needs to do is to formulate a long-term policy on Kashmir that includes mending ties with neighbours, improving law and order, ending human rights abuses—especially in Balochistan—and above all strengthening its feeble economy,” Qazi explains.

The need for an effective policy is not an insignificant subject for the Kashmiris who look to Pakistan for moral, political and ethical support. Hurriyat Conference Chairman Miwaiz Umer Farooq says Kashmiri hearts and minds are with Pakistan and they want Pakistan to internationalise the issue. Talking about Modi’s statement on Balochistan, Mirwaiz said: “India wants to give the impression to its people that the way Pakistan talks about Kashmir they (India) too would point out excesses in Pakistan.”

The quagmire of national politics (Panama Leaks, Altaf Hussain) has kept Pakistan from forming a unified response to India let alone a concrete policy. This is exacerbated by a lack of consultative process among former diplomats and policy-makers on Kashmir.

Faisal Shakeel is an anchor for Current Affairs on Waqt TV and tweets at @sfaisalshakeel