An American researcher who learnt about “The World of Islam” as a student of my father in Washington DC recently told me that once while he was walking down a street during a field research project on a pleasant summer’s day in Florida, he met a friendly old woman who was gardening. They struck up a conversation during which he told her that he had been on an exciting learning research project called Journey into Islam, a project which visited nine Muslim countries including Pakistan. She stopped his conversation exclaiming, “Wait! What? Pakistan!?”. Then, after a pause, she said, “Do people love their children, there?”

He calmly replied, “Yes, they do: just like us. They are very family-oriented and are indeed very loving to their children”. The woman from Florida shouted back in the direction of her husband, “See darling, I told you they love their children there”. The woman explained that negative images of Pakistan dominate the local news. However, she owned a sweater that had the words ‘Made in Pakistan’ on it which gave her hope that people “out there” did positive and constructive things. The old woman felt deep down that people everywhere in the world were good and productive – her sweater spoke more to her, in this case, than the negative image of Pakistan that has been systematically received through the media in the West.

Images are built of countries as images are built of men and women: this one is a “good” one; that one is “bad”. This one is “friendly”; that is an “enemy”. However, beneath this surface of media information and propaganda in which each county perceives itself as inherently good and “the Other” as inherently evil, there are real people struggling to survive, to find their next meal, to live a life of dignity.

Images are indeed based on histories, encounters, and the ability of those represented to fight for an equal voice to represent and speak for themselves. Creating negative images of “the Other” is deeply problematic for the idea of human morality, as it implicitly rationalizes the condoning of violence against perceived others.

Negative images of “the Other” are not in any way helpful: not to the ones behind this construction, or to the world, the consumers, and especially not to those portrayed in negative ways as it drives people into a self-fulfilling prophecy of negativity and pushes them towards the periphery. In an interconnected world, the marginalization of certain countries only demoralizes and demonizes people, and may push them into roles that are unconstructive. There is a growing number of immigrants in the West from Muslim countries, and media depictions of Muslims and Pakistanis can cause unnecessary distancing between locals and immigrants (all South Asians get affected – Sikhs and Hindus have been beaten up by those in New York thinking they are all “Pakis”). The media depictions of “the Other”, at present, drive people apart and create walls of misunderstanding, dangerous distances, and lack of mutual respect. Instead, I think, the media can and should bring the world closer together through equal representation in conflict stories, fair coverage, and a more scholarly and positive analysis.

It is important to highlight here the point that although the global media has created a panic over terrorism, it is the ordinary people, especially those in Pakistan (for example the victims of the Peshawar army school attack, the ordinary people in tribal areas and the people who died in the churches attacked in Lahore) who are the real victims of terrorism. While the Western media tends to paint a simplistic image of Pakistan as the hub of extremist activities, in reality the majority of Pakistanis are the victims of terrorism (thousands of innocent people in Pakistan have died since 9/11).

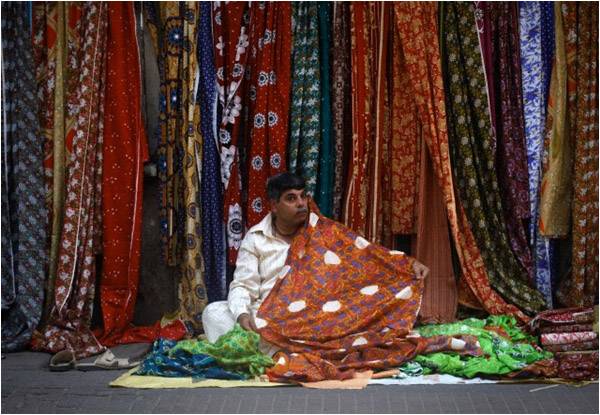

Before we can take the first step towards creating a peaceful world, we have to stop building barriers between “them” versus “us”. There is much more to the story than simply “good guys” and “bad guys”: “good countries” and “bad countries”. Reality is far more complex and there is both good and bad in every story and history of nations. Understanding history and reading about the perceived “Other” helps. In Pakistan in particular, a country of two hundred million people, everyday life goes on: mothers drive their children to school, teachers begin the effort of teaching little reluctant 4 year old children how to read and write, and where female friends meet at their homes over chai in their beautiful cotton/lawn clothes and khussas (local leather shoes) – all “Made in Pakistan” (here are some more things that are made in Pakistan and exported to the world: cotton and textiles; cutlery; rugs and carpets, fans; rice, salt, seafood, apples, oranges and mangoes. 80% of the world’s footballs are made in Pakistan). As they go about their lives, though, ordinary Pakistanis continue to worry about the safety of their beloved homeland. After the Peshawar attack, I saw teachers, students, and staff in schools in a state of shock and trauma. Principals were concerned about terrorism and the continuous cycle of revenge and recognized the role that the demonization of the “Other” plays in this violence. I met one such principal, the seasoned and dynamic Mrs Pracha, who was so saddened by Peshawar she said she could not function for ten days, despite a pile of papers demanding attention waiting on her desk. Even in her despair, however, she would heroically not be discouraged from her mission of opening young minds to the world of knowledge and science and told me something that we should remember in these difficult times and can give us hope: “I am reminded of what Abraham Lincoln wrote to his son’s teacher: ‘Teach him that for every enemy there is a friend.’” In fact, one must consider going even further and encourage the next generation to work towards converting all enmities into friendships through dialogue, mutual respect and understanding.

Dr Amineh Hoti is the executive director of the Centre for Dialogue and Action at Forman Christian College, Lahore

He calmly replied, “Yes, they do: just like us. They are very family-oriented and are indeed very loving to their children”. The woman from Florida shouted back in the direction of her husband, “See darling, I told you they love their children there”. The woman explained that negative images of Pakistan dominate the local news. However, she owned a sweater that had the words ‘Made in Pakistan’ on it which gave her hope that people “out there” did positive and constructive things. The old woman felt deep down that people everywhere in the world were good and productive – her sweater spoke more to her, in this case, than the negative image of Pakistan that has been systematically received through the media in the West.

Images are built of countries as images are built of men and women: this one is a “good” one; that one is “bad”. This one is “friendly”; that is an “enemy”. However, beneath this surface of media information and propaganda in which each county perceives itself as inherently good and “the Other” as inherently evil, there are real people struggling to survive, to find their next meal, to live a life of dignity.

Images are indeed based on histories, encounters, and the ability of those represented to fight for an equal voice to represent and speak for themselves. Creating negative images of “the Other” is deeply problematic for the idea of human morality, as it implicitly rationalizes the condoning of violence against perceived others.

Negative images of “the Other” are not in any way helpful: not to the ones behind this construction, or to the world, the consumers, and especially not to those portrayed in negative ways as it drives people into a self-fulfilling prophecy of negativity and pushes them towards the periphery. In an interconnected world, the marginalization of certain countries only demoralizes and demonizes people, and may push them into roles that are unconstructive. There is a growing number of immigrants in the West from Muslim countries, and media depictions of Muslims and Pakistanis can cause unnecessary distancing between locals and immigrants (all South Asians get affected – Sikhs and Hindus have been beaten up by those in New York thinking they are all “Pakis”). The media depictions of “the Other”, at present, drive people apart and create walls of misunderstanding, dangerous distances, and lack of mutual respect. Instead, I think, the media can and should bring the world closer together through equal representation in conflict stories, fair coverage, and a more scholarly and positive analysis.

There is much more to the story than simply good guys and bad guys

It is important to highlight here the point that although the global media has created a panic over terrorism, it is the ordinary people, especially those in Pakistan (for example the victims of the Peshawar army school attack, the ordinary people in tribal areas and the people who died in the churches attacked in Lahore) who are the real victims of terrorism. While the Western media tends to paint a simplistic image of Pakistan as the hub of extremist activities, in reality the majority of Pakistanis are the victims of terrorism (thousands of innocent people in Pakistan have died since 9/11).

Before we can take the first step towards creating a peaceful world, we have to stop building barriers between “them” versus “us”. There is much more to the story than simply “good guys” and “bad guys”: “good countries” and “bad countries”. Reality is far more complex and there is both good and bad in every story and history of nations. Understanding history and reading about the perceived “Other” helps. In Pakistan in particular, a country of two hundred million people, everyday life goes on: mothers drive their children to school, teachers begin the effort of teaching little reluctant 4 year old children how to read and write, and where female friends meet at their homes over chai in their beautiful cotton/lawn clothes and khussas (local leather shoes) – all “Made in Pakistan” (here are some more things that are made in Pakistan and exported to the world: cotton and textiles; cutlery; rugs and carpets, fans; rice, salt, seafood, apples, oranges and mangoes. 80% of the world’s footballs are made in Pakistan). As they go about their lives, though, ordinary Pakistanis continue to worry about the safety of their beloved homeland. After the Peshawar attack, I saw teachers, students, and staff in schools in a state of shock and trauma. Principals were concerned about terrorism and the continuous cycle of revenge and recognized the role that the demonization of the “Other” plays in this violence. I met one such principal, the seasoned and dynamic Mrs Pracha, who was so saddened by Peshawar she said she could not function for ten days, despite a pile of papers demanding attention waiting on her desk. Even in her despair, however, she would heroically not be discouraged from her mission of opening young minds to the world of knowledge and science and told me something that we should remember in these difficult times and can give us hope: “I am reminded of what Abraham Lincoln wrote to his son’s teacher: ‘Teach him that for every enemy there is a friend.’” In fact, one must consider going even further and encourage the next generation to work towards converting all enmities into friendships through dialogue, mutual respect and understanding.

Dr Amineh Hoti is the executive director of the Centre for Dialogue and Action at Forman Christian College, Lahore