There is very little to write about these days except the COVID-19 pandemic. But most human activities, including politics and war, do not stop during pandemics, although their trajectories may bend radically. Two things are clear about pandemics: they are caused by viruses or other bacteria to which innocent people have not developed immunity and, therefore, they are widely lethal; and that they have often changed the course of history in fundamental ways. These changes are not predictable.

In South Asia, despite the onset of pandemic in all the countries of the region, politics will continue, framed in the context if subduing the Coronavirus outbreak. War will continue too, but framed mostly in the context of the Afghan peace process aimed at ending that 30-year civil war (also known as the longest war in US history - a misnomer). The Afghan peace process has moved to the back pages of newspapers and 30-second mentions, if at all, on TV news. This seems to be the case also in Pakistan, if a quick look at today’s electronic version of Dawn is any indication. The pandemic took up the entire front page and all subsequent national pages; the Afghan peace process only appeared on the second page of international coverage.

The serious question is, however, not whether politics will continue, but what impact the pandemic will have on these countries politically and economically, and on the peace process itself. While history hides its innermost trends, we know that fundamental changes in the politics, or the political and economic structures and institutions themselves, could result from a pandemic which seems currently almost impossible to stop or mitigate. The changes in South Asian societies, the surrounding region and the world in general are likely to make political and economic issues and security issues look very different in a few years.

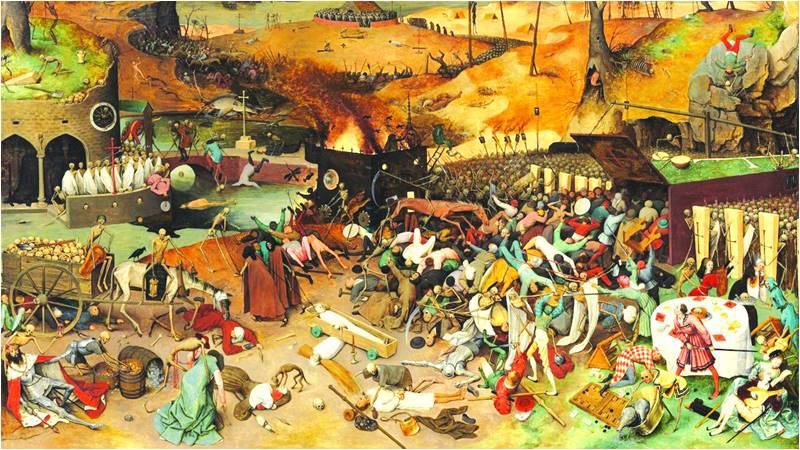

The impact of pandemics can be fundamental and structural. In the 14th century the most famous of pandemics, the Bubonic Plague, devastated most of the world. Fairly recent research indicates that it originated in Mongolia or the region near there in the 1330s and spread slowly South and West and reached Eastern Europe by 1347, when the Mongols attacked and besieged an Italian trading station on the Caspian Sea. When the besieged Italians escaped by sea, they brought the epidemic to Europe where it devastated that continent. It came and went for a decade and killed an estimated one third to one half of the European population. The impact cannot be overstated and was deeply transformational. Its core cause was demographic: labor became much more expensive and this transferred power to the working classes and to the middle class. Structural change, such as the slow chipping away at feudalism, was accelerated greatly. Many historians believe this began the great transformation that moved European societies into modernity, accelerated the decline of arbitrary monarchial and aristocratic power and hastened the advent of more representative government. It stopped wars; England and France were so weakened that they called a truce to the 100 years war. The Vikings stopped their raiding of Western Europe and their exploration of North America. How different might we Americans have been if our founding fathers had been of Scandinavian origin?

This Bubonic Plague pandemic had been preceded by what is called the Justinian Plague of the 6th century. It spread from Egypt to Constantinople, the seat of the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire. Its relationship to the later Bubonic Plague is not clear, but its symptoms were similar. This pandemic disrupted the Emperor Justinian form reuniting the then-ruptured Eastern and Western parts of the Roman Empire. This plague revisited the empire over the next two centuries and ended up killing about a quarter of the world population. Some historians believe that the apocalyptic mindset it created in the lower classes led to the more rapid growth of Christianity.

Now we come to the most devastating and significant pandemic since the 14th century Bubonic Plague, the consequences of which had equal, if not more, significance impact on politics and economics of its time. And these consequences were the result not of the large number of deaths, although the death toll was enormous, but of factors more insidious and generally misunderstood. The 1918-19 Spanish Flu pandemic did not originate in Spain, an innocent bystander, so to speak, but apparently in the United States, in the state of Kansas when a virus that infected swine jumped to humans. It came at the worst time possible, when most of the great powers of the world were at war with each other. World War 1 (1914-18) ended in November of 1918; the pandemic broke out in January of that year in US Army training camps. The Americans carried the virus to Europe, and many of the deaths in those trenches in the final months of the war were from the influenza, not from enemy fire.

The US and its allies responded as most governments at war would as the pandemic spread through the trenches of Europe. They imposed strict censorship so the truth, even the fact, of a pandemic was hidden from the publics of the warring nations until it could not be any longer, and this delay certainly was responsible for a large number of the deaths, as nations could not prepare properly for the onslaught of a virus that humans had not experienced before and which was as contagious at least as the plagues of old. Ultimately, this virus killed somewhere between 20 and 50 million people in the world, and some estimates go as high as 100 million. From their study of this pandemic, epidemiological experts are unanimous on the need for total transparency in a pandemic, yet governments (including both the US and the Chinese) have repeated the same mistake, though not so long or so pervasively this time around.

The significant political and economic impact I refer to were the result of world leaders catching that flu. In a remarkable book first published 16 years ago, The Great Influenza, author John Barry, describes in about five very terse pages toward the end of the book the scene at the Versailles Peace Conference in 1919. Though thousands attended this conference, only three men mattered: Prime Minister Lloyd George of the UK, weakened by serious political trouble at home; Premier Georges Clemenceau of France, wounded in a recent assassination attempt but with a well-known proclivity for vindictiveness; and President Woodrow Wilson of the United States, who was at that time, Barry points out, “the most popular political figure in the world.” They were, Barry writes, “deciding the future of the world.”

All three had the flu, but Wilson’s case was much worse and began to involve mental lapses. “Then abruptly still on his sickbed, only a few days after he [Wilson] had threatened to leave the conference unless Clemenceau yielded in his demands, without warning to or discussion with any other Americans, Wilson suddenly abandoned principles he had previously insisted upon. He yielded to Clemenceau everything of significance Clemenceau wanted, virtually all of which Wilson had earlier opposed.” He had given way on the questions of massive reparations, German responsibility for the war, a demilitarised Rhineland, French control of the coal mines of the Saar, the return of Alsace and Loraine to France, giving East Prussia to Poland, creating the Polish Corridor, limiting German to 100,000 men, giving German colonies to other countries. Wilson had arrived at the conference with his famous 14 points famously summed up in his phrase “peace without victory.” These concessions violated all of them.

Historians have routinely thought that Wilson suffered a minor stroke in Paris, a precursor to his major stroke four months later. But Barry’s description and argument that Wilson was another victim of the Spanish influenza is totally compelling. And thus, the concessions he made leading to the very vindictive Versailles Treaty, which almost all historians agree was the prime cause of German revanchism and the revival of extreme nationalism in the figure of Adolph Hitler and his Nazi Party means the Spanish flu was also at least partly responsible for the rise of authoritarian and totalitarian parties in Europe in the 1920s and 1930s and the Second World War.

The writer is a diplomat and is Senior Policy Scholar at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C.

In South Asia, despite the onset of pandemic in all the countries of the region, politics will continue, framed in the context if subduing the Coronavirus outbreak. War will continue too, but framed mostly in the context of the Afghan peace process aimed at ending that 30-year civil war (also known as the longest war in US history - a misnomer). The Afghan peace process has moved to the back pages of newspapers and 30-second mentions, if at all, on TV news. This seems to be the case also in Pakistan, if a quick look at today’s electronic version of Dawn is any indication. The pandemic took up the entire front page and all subsequent national pages; the Afghan peace process only appeared on the second page of international coverage.

The serious question is, however, not whether politics will continue, but what impact the pandemic will have on these countries politically and economically, and on the peace process itself. While history hides its innermost trends, we know that fundamental changes in the politics, or the political and economic structures and institutions themselves, could result from a pandemic which seems currently almost impossible to stop or mitigate. The changes in South Asian societies, the surrounding region and the world in general are likely to make political and economic issues and security issues look very different in a few years.

The impact of pandemics can be fundamental and structural. In the 14th century the most famous of pandemics, the Bubonic Plague, devastated most of the world. Fairly recent research indicates that it originated in Mongolia or the region near there in the 1330s and spread slowly South and West and reached Eastern Europe by 1347, when the Mongols attacked and besieged an Italian trading station on the Caspian Sea. When the besieged Italians escaped by sea, they brought the epidemic to Europe where it devastated that continent. It came and went for a decade and killed an estimated one third to one half of the European population. The impact cannot be overstated and was deeply transformational. Its core cause was demographic: labor became much more expensive and this transferred power to the working classes and to the middle class. Structural change, such as the slow chipping away at feudalism, was accelerated greatly. Many historians believe this began the great transformation that moved European societies into modernity, accelerated the decline of arbitrary monarchial and aristocratic power and hastened the advent of more representative government. It stopped wars; England and France were so weakened that they called a truce to the 100 years war. The Vikings stopped their raiding of Western Europe and their exploration of North America. How different might we Americans have been if our founding fathers had been of Scandinavian origin?

This Bubonic Plague pandemic had been preceded by what is called the Justinian Plague of the 6th century. It spread from Egypt to Constantinople, the seat of the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire. Its relationship to the later Bubonic Plague is not clear, but its symptoms were similar. This pandemic disrupted the Emperor Justinian form reuniting the then-ruptured Eastern and Western parts of the Roman Empire. This plague revisited the empire over the next two centuries and ended up killing about a quarter of the world population. Some historians believe that the apocalyptic mindset it created in the lower classes led to the more rapid growth of Christianity.

Now we come to the most devastating and significant pandemic since the 14th century Bubonic Plague, the consequences of which had equal, if not more, significance impact on politics and economics of its time. And these consequences were the result not of the large number of deaths, although the death toll was enormous, but of factors more insidious and generally misunderstood. The 1918-19 Spanish Flu pandemic did not originate in Spain, an innocent bystander, so to speak, but apparently in the United States, in the state of Kansas when a virus that infected swine jumped to humans. It came at the worst time possible, when most of the great powers of the world were at war with each other. World War 1 (1914-18) ended in November of 1918; the pandemic broke out in January of that year in US Army training camps. The Americans carried the virus to Europe, and many of the deaths in those trenches in the final months of the war were from the influenza, not from enemy fire.

The US and its allies responded as most governments at war would as the pandemic spread through the trenches of Europe. They imposed strict censorship so the truth, even the fact, of a pandemic was hidden from the publics of the warring nations until it could not be any longer, and this delay certainly was responsible for a large number of the deaths, as nations could not prepare properly for the onslaught of a virus that humans had not experienced before and which was as contagious at least as the plagues of old. Ultimately, this virus killed somewhere between 20 and 50 million people in the world, and some estimates go as high as 100 million. From their study of this pandemic, epidemiological experts are unanimous on the need for total transparency in a pandemic, yet governments (including both the US and the Chinese) have repeated the same mistake, though not so long or so pervasively this time around.

The significant political and economic impact I refer to were the result of world leaders catching that flu. In a remarkable book first published 16 years ago, The Great Influenza, author John Barry, describes in about five very terse pages toward the end of the book the scene at the Versailles Peace Conference in 1919. Though thousands attended this conference, only three men mattered: Prime Minister Lloyd George of the UK, weakened by serious political trouble at home; Premier Georges Clemenceau of France, wounded in a recent assassination attempt but with a well-known proclivity for vindictiveness; and President Woodrow Wilson of the United States, who was at that time, Barry points out, “the most popular political figure in the world.” They were, Barry writes, “deciding the future of the world.”

All three had the flu, but Wilson’s case was much worse and began to involve mental lapses. “Then abruptly still on his sickbed, only a few days after he [Wilson] had threatened to leave the conference unless Clemenceau yielded in his demands, without warning to or discussion with any other Americans, Wilson suddenly abandoned principles he had previously insisted upon. He yielded to Clemenceau everything of significance Clemenceau wanted, virtually all of which Wilson had earlier opposed.” He had given way on the questions of massive reparations, German responsibility for the war, a demilitarised Rhineland, French control of the coal mines of the Saar, the return of Alsace and Loraine to France, giving East Prussia to Poland, creating the Polish Corridor, limiting German to 100,000 men, giving German colonies to other countries. Wilson had arrived at the conference with his famous 14 points famously summed up in his phrase “peace without victory.” These concessions violated all of them.

Historians have routinely thought that Wilson suffered a minor stroke in Paris, a precursor to his major stroke four months later. But Barry’s description and argument that Wilson was another victim of the Spanish influenza is totally compelling. And thus, the concessions he made leading to the very vindictive Versailles Treaty, which almost all historians agree was the prime cause of German revanchism and the revival of extreme nationalism in the figure of Adolph Hitler and his Nazi Party means the Spanish flu was also at least partly responsible for the rise of authoritarian and totalitarian parties in Europe in the 1920s and 1930s and the Second World War.

The writer is a diplomat and is Senior Policy Scholar at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C.