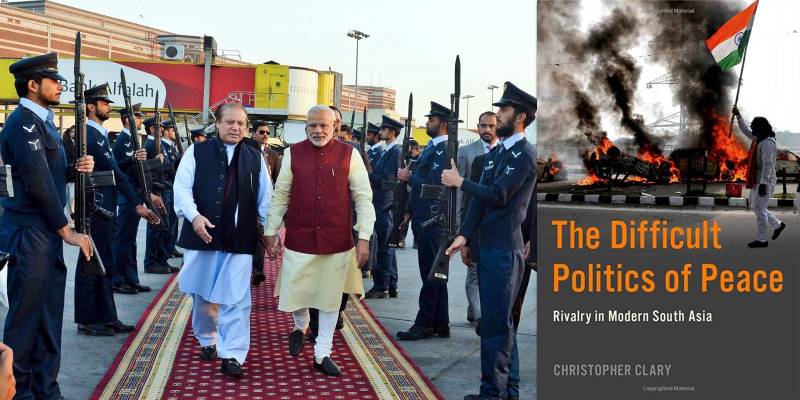

Book Review: The Difficult Politics of Peace: Rivalry in Modern South Asia (New York: Oxford University Press, 2022)

Christopher Clary’s The Difficult Politics of Peace: Rivalry in Modern South Asia has three outstanding features: first, it is theoretically innovative and refreshing in its approach, content, and style. Second, the volume is methodologically rigorous and evidence driven, unearthing new archives, and third, it cuts across disciplinary boundaries. The author is upfront in arguing that conventional portrayals of India and Pakistan as caught in a vicious cycle of ‘conflict unending’ does not reveal the complete picture and at best is, ‘incomplete.’

Cognizant of this reality, Clary ventures to trace the difficult politics of peace in modern South Asia, and in the process sheds light on the complexity of leadership, motivations, deeply entrenched antagonisms and thus brings to light the primacy of leadership theory to untangle the process of peace between India and Pakistan. Clary boldly ventures to propose, that ‘the disproportionate focus’ of existing accounts on Kashmir is on crisis and war, and not on peace, and therefore, he presents an alternative lens, building peace through the primacy of leadership theory. Clary argues that both peacebuilding and war-making must consider the primacy of leadership, so that we can fully understand why peace-building efforts have failed many a times in such a tragic and “spectacular fashion.” He digs deep into the history, culture and psyche of the India and Pakistan rivalry.

Clary draws our attention to a reality hitherto ignored or inadequately addressed in the literature on state rivalries - that states confronted with national insecurity evoke the rise of domestic hardline factions. These factions, in turn, invariably have diverging views on how to design and manage the foreign policy of the state. Fragmentated and fractured domestic leadership incites violence and makes the pursuit of peace difficult. These internal factions offer diverging views on how to seek peace or war to preserve national security in India and Pakistan.

According to the author, the primacy of leadership implies that the leader must not only be ambitious to seek ‘concentration of power,’ but also be skillful enough to utilize it effectively to win over the domestic opponents to peace in line with the leader’s choice to counter or cooperate with the ‘external adversary.’ Thus, the author incisively observes that ‘leaders are unwilling or unable to sustain conciliatory initiatives unless and until they have consolidated authority over foreign policy within their governments.’

Clary recognizes and concedes that this precondition of accumulating power at times leads to leaders becoming ‘authoritarian’ and seeking to acquire too much power, and he highlights the case of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto and Indira Gandhi in the 1970s. Chapters 5, 6 and 7 make an engaging read on the theory of primacy of leadership. The author analyzes how military and civilian leadership in Pakistan and India (1971-1999), while ‘consolidating power’, manifested an authoritarian streak and yet were able to diffuse several tense situations and succeeded in avoiding war, thereby creating temporary peace – the state of no war. The author reveals his fascination with Bhutto, trying to demystify his enigmatic leadership. In this case, leadership primacy theory both resonates and falters as the author, in more than one place, draws insights from diplomats such as McGeorge Bundy and scholars like Stanley Wolpert, and sheds light on Bhutto’s skills as negotiator, political strategist and yet labels him as an ‘evil’ leader. In a similar way, the characterization of Indira Gandhi is equally absorbing and highlights the making of an authoritarian and crafty leader, with the author depicting her as ‘an Empress.’

According to Clary, while Rajiv Gandhi struggles to establish primacy in the late 1980s with Benazir Bhutto on the other side, both were moderates and weak, and therefore stumbled before domestic hawks. Thus, the two despite their best intent, could not incentivize peace.

The book is neatly divided into eight chapters, with a short introduction and conclusion. Each chapter analyses an era, underscoring primacy of leadership and weaving events and points of conflict and processes around it. From chapters 4 to 8, the author offers a critical appraisal of existing arguments and perspectives, while underscoring the salience and robustness of leadership primacy theory.

In chapter 1, the author dwells upon the need to studying rivalries and in that context formulates Leadership Primacy Theory, while searching for a cogent answer to the question of how and why leadership primacy is imperative for peace building in rival states. Clary argues that concentration of power and authority enables leaders to seek peace or war. Fractured authority in the foreign policy arena does not help in pursuing a coherent foreign policy. In the cases of Ayub and Musharraf, he points out, how both leaders initially consolidated power but subsequently lost it -- so primacy does not always mean sustainable leadership. It can be lost and therefore, we need to understand how leaders acquire and lose primacy in the making of foreign policy. In a similar way, the persuasive skills and leadership attributes of Nehru, Shastri, Desai, Indira Gandhi, and Vajpayee are analyzed in the Indian context.

While expounding on the leadership primacy theory, in a rather nuanced way, the book also sheds light on civil–military relations and the role of civil and military institutions in foreign policy making. For example, comparing Pakistan and India’s leadership dispositions, he observes that during 1977-88, while in Pakistan, Zia consolidated his power and remained the dominant leader, India had five different governments under four prime-ministers—Indira, Desai, V.P Singh, Indira again and Rajiv, and none was strong enough to pursue peace, so fractured leadership offered little incentive for peace.

Thus, the study identifies patterns of conflict, episodic peace, and moments of hope. The book presents a comprehensive and in-depth historical overview of the rivalry between India and Pakistan, from the partition of British India in 1947 to the latest episodes of escalation in 2019 and 2020, all the while keeping a spotlight on the primacy of leadership and the contentious issues of Kashmir. Clary boldly claims that “national leaders in India and Pakistan have often refused to merely settle for small spaces of cooperation carved out amid broader conflict and have attempted ambitious efforts to transform the relationship towards a more durable peace—with varying levels of success.” This insight implies that leaders in the two countries do aspire for and harbor intentions to bring about a comprehensive peace, but domestic rival extremists and the fracturing of leadership allow for intense resistance to peace overtures, which perpetuates the rivalry.

Methodological rigor and fresh evidence are another distinguishing feature of this book. The author has been able to tap into a wealth of recently declassified documents by the US, UK, and India. That is significant contribution in terms of unearthing new documents and archives. The book provides a rich, voluminous and detailed analysis of the Kashmir dispute under different eras, regimes, and leaders, which is duly corroborated by interviews with Indian, Pakistani and American officials and diplomats. In addition, the literature review is robust and wide-ranging.

Finally, while making a strong and persuasive case for leadership primacy in conflict resolution and peace development, the author still leaves the reader somewhat baffled, insofar as the author suggests that leadership primacy is “not an unalloyed good,” and that it “does not permit escape” from “fundamental dilemmas.”

In my view, advocating a theory and yet showing skepticism about its limitations and applicability is also a sign of sound scholarship. Recognizing the limitations of his theory’s focus on only one rivalry—India and Pakistan, he reminds readers of the emergence of the U.S- China rivalry under Trump, and its intensification under Biden. Thus, peeping into the near future, Clary alludes that the India-China rivalry may replace Pakistan, and that invites further research on the applicability of leadership primacy theory.

Political analysts, policy makers, political party leaders, NGOs supporting the peace process and students and scholars interested in the practical challenges that leaders confront on the domestic front while shaping their foreign policies in pursuit of peace will find the book illuminating.

Christopher Clary’s The Difficult Politics of Peace: Rivalry in Modern South Asia has three outstanding features: first, it is theoretically innovative and refreshing in its approach, content, and style. Second, the volume is methodologically rigorous and evidence driven, unearthing new archives, and third, it cuts across disciplinary boundaries. The author is upfront in arguing that conventional portrayals of India and Pakistan as caught in a vicious cycle of ‘conflict unending’ does not reveal the complete picture and at best is, ‘incomplete.’

Clary draws our attention to a reality hitherto ignored or inadequately addressed in the literature on state rivalries - that states confronted with national insecurity evoke the rise of domestic hardline factions.

Cognizant of this reality, Clary ventures to trace the difficult politics of peace in modern South Asia, and in the process sheds light on the complexity of leadership, motivations, deeply entrenched antagonisms and thus brings to light the primacy of leadership theory to untangle the process of peace between India and Pakistan. Clary boldly ventures to propose, that ‘the disproportionate focus’ of existing accounts on Kashmir is on crisis and war, and not on peace, and therefore, he presents an alternative lens, building peace through the primacy of leadership theory. Clary argues that both peacebuilding and war-making must consider the primacy of leadership, so that we can fully understand why peace-building efforts have failed many a times in such a tragic and “spectacular fashion.” He digs deep into the history, culture and psyche of the India and Pakistan rivalry.

Clary draws our attention to a reality hitherto ignored or inadequately addressed in the literature on state rivalries - that states confronted with national insecurity evoke the rise of domestic hardline factions. These factions, in turn, invariably have diverging views on how to design and manage the foreign policy of the state. Fragmentated and fractured domestic leadership incites violence and makes the pursuit of peace difficult. These internal factions offer diverging views on how to seek peace or war to preserve national security in India and Pakistan.

According to the author, the primacy of leadership implies that the leader must not only be ambitious to seek ‘concentration of power,’ but also be skillful enough to utilize it effectively to win over the domestic opponents to peace in line with the leader’s choice to counter or cooperate with the ‘external adversary.’ Thus, the author incisively observes that ‘leaders are unwilling or unable to sustain conciliatory initiatives unless and until they have consolidated authority over foreign policy within their governments.’

Clary recognizes and concedes that this precondition of accumulating power at times leads to leaders becoming ‘authoritarian’ and seeking to acquire too much power, and he highlights the case of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto and Indira Gandhi in the 1970s. Chapters 5, 6 and 7 make an engaging read on the theory of primacy of leadership. The author analyzes how military and civilian leadership in Pakistan and India (1971-1999), while ‘consolidating power’, manifested an authoritarian streak and yet were able to diffuse several tense situations and succeeded in avoiding war, thereby creating temporary peace – the state of no war. The author reveals his fascination with Bhutto, trying to demystify his enigmatic leadership. In this case, leadership primacy theory both resonates and falters as the author, in more than one place, draws insights from diplomats such as McGeorge Bundy and scholars like Stanley Wolpert, and sheds light on Bhutto’s skills as negotiator, political strategist and yet labels him as an ‘evil’ leader. In a similar way, the characterization of Indira Gandhi is equally absorbing and highlights the making of an authoritarian and crafty leader, with the author depicting her as ‘an Empress.’

According to Clary, while Rajiv Gandhi struggles to establish primacy in the late 1980s with Benazir Bhutto on the other side, both were moderates and weak, and therefore stumbled before domestic hawks. Thus, the two despite their best intent, could not incentivize peace.

The book is neatly divided into eight chapters, with a short introduction and conclusion. Each chapter analyses an era, underscoring primacy of leadership and weaving events and points of conflict and processes around it. From chapters 4 to 8, the author offers a critical appraisal of existing arguments and perspectives, while underscoring the salience and robustness of leadership primacy theory.

Leaders in the two countries do aspire for and harbor intentions to bring about a comprehensive peace, but domestic rival extremists and the fracturing of leadership allow for intense resistance to peace overtures, which perpetuates the rivalry.

In chapter 1, the author dwells upon the need to studying rivalries and in that context formulates Leadership Primacy Theory, while searching for a cogent answer to the question of how and why leadership primacy is imperative for peace building in rival states. Clary argues that concentration of power and authority enables leaders to seek peace or war. Fractured authority in the foreign policy arena does not help in pursuing a coherent foreign policy. In the cases of Ayub and Musharraf, he points out, how both leaders initially consolidated power but subsequently lost it -- so primacy does not always mean sustainable leadership. It can be lost and therefore, we need to understand how leaders acquire and lose primacy in the making of foreign policy. In a similar way, the persuasive skills and leadership attributes of Nehru, Shastri, Desai, Indira Gandhi, and Vajpayee are analyzed in the Indian context.

While expounding on the leadership primacy theory, in a rather nuanced way, the book also sheds light on civil–military relations and the role of civil and military institutions in foreign policy making. For example, comparing Pakistan and India’s leadership dispositions, he observes that during 1977-88, while in Pakistan, Zia consolidated his power and remained the dominant leader, India had five different governments under four prime-ministers—Indira, Desai, V.P Singh, Indira again and Rajiv, and none was strong enough to pursue peace, so fractured leadership offered little incentive for peace.

Thus, the study identifies patterns of conflict, episodic peace, and moments of hope. The book presents a comprehensive and in-depth historical overview of the rivalry between India and Pakistan, from the partition of British India in 1947 to the latest episodes of escalation in 2019 and 2020, all the while keeping a spotlight on the primacy of leadership and the contentious issues of Kashmir. Clary boldly claims that “national leaders in India and Pakistan have often refused to merely settle for small spaces of cooperation carved out amid broader conflict and have attempted ambitious efforts to transform the relationship towards a more durable peace—with varying levels of success.” This insight implies that leaders in the two countries do aspire for and harbor intentions to bring about a comprehensive peace, but domestic rival extremists and the fracturing of leadership allow for intense resistance to peace overtures, which perpetuates the rivalry.

Methodological rigor and fresh evidence are another distinguishing feature of this book. The author has been able to tap into a wealth of recently declassified documents by the US, UK, and India. That is significant contribution in terms of unearthing new documents and archives. The book provides a rich, voluminous and detailed analysis of the Kashmir dispute under different eras, regimes, and leaders, which is duly corroborated by interviews with Indian, Pakistani and American officials and diplomats. In addition, the literature review is robust and wide-ranging.

Finally, while making a strong and persuasive case for leadership primacy in conflict resolution and peace development, the author still leaves the reader somewhat baffled, insofar as the author suggests that leadership primacy is “not an unalloyed good,” and that it “does not permit escape” from “fundamental dilemmas.”

In my view, advocating a theory and yet showing skepticism about its limitations and applicability is also a sign of sound scholarship. Recognizing the limitations of his theory’s focus on only one rivalry—India and Pakistan, he reminds readers of the emergence of the U.S- China rivalry under Trump, and its intensification under Biden. Thus, peeping into the near future, Clary alludes that the India-China rivalry may replace Pakistan, and that invites further research on the applicability of leadership primacy theory.

Political analysts, policy makers, political party leaders, NGOs supporting the peace process and students and scholars interested in the practical challenges that leaders confront on the domestic front while shaping their foreign policies in pursuit of peace will find the book illuminating.