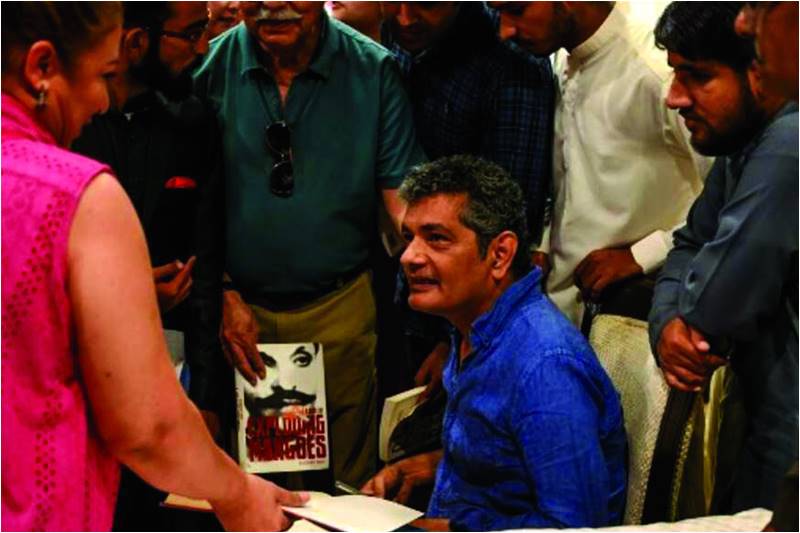

I read A Case of Exploding Mangoes by the inimitable Mohammed Hanif when it came out over a decade ago. Set in the final days before General Zia’s mysterious and timely plane crash, the book was feted around the world as a masterclass in literary political satire. Reading it was an exhilarating experience, a breath of fresh air really – partly because it was extremely well-written but mainly because I couldn’t believe it was being disseminated in Pakistan. The security apparatus and its relationship with the state, though omnipresent, had never been open game for humour. And released as it was during the tenure of another erstwhile military dictator General Musharraf, the book’s appearance was both timely and bravely seminal. It made the rounds of the literary circuits in Pakistan and abroad, gathering up prizes including being long listed for the Booker Prize. That it was allowed to flourish unchallenged as it did, I took as a sign that things were changing in Pakistan. Perhaps we did have a sense of humour about ourselves?

Spoiler Alert: We don’t.

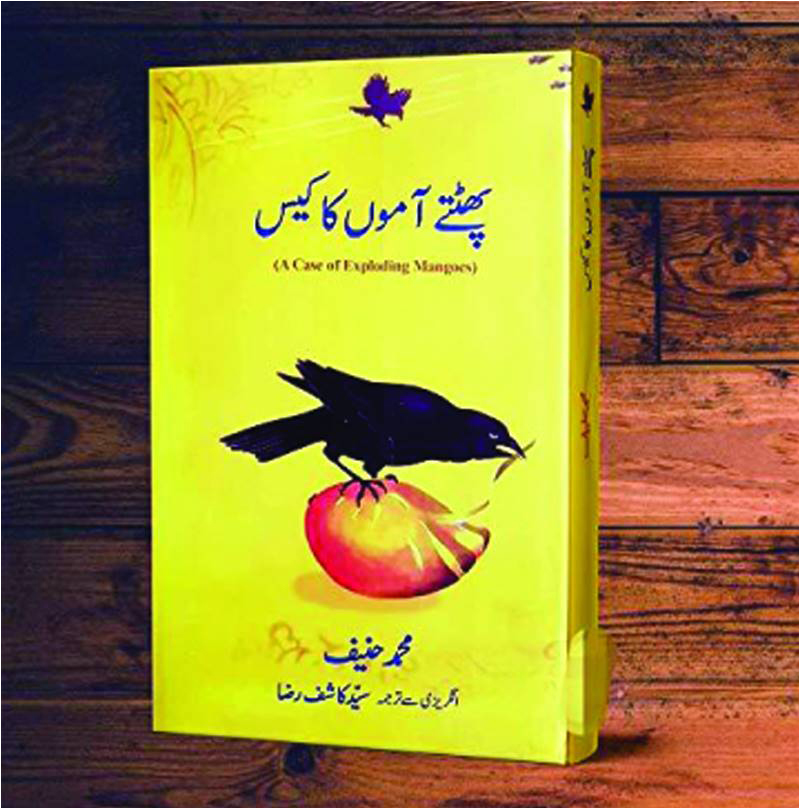

This week the book made headlines again because the offices of the local publishers of the novel were raided by men claiming to be from security institutions. In addition, General Zia’s son has issue a defamation suit for 1 billion rupees against them for “maligning the former ruler’s name”, years after he had presumably been told his father was the subject of a bestselling novel. The book has been readily available in Pakistan for years, so what changed? The language. It’s being published in Urdu. The raid and defamation notice are the clearest signs yet of exactly how the state values the danger of cultural products based on their intended audience.

English language novels (or articles, papers, channels, people) are generally ignored by the state for the same reasons that most of the ramblings in this column or contemporary art galleries or English newspapers don’t matter to them: the audience demographic is too small to matter, or else irrelevant. But Hanif’s work, himself brilliant in both Urdu and English, is different. Humour, particularly political humour, can cut through the pretensions of class and outlook with just a chuckle. Its the way stand-up comics enchant crowds of thousands. A shared laugh is a shared connection, and a shared laugh by readers at Zia’s expense in Urdu is clearly a much more threatening thing than a glowing New York Times review.

It is my hope that nothing will come of the harassment of the publishers or the defamation case. As a public domain figure General Zia is as appropriate as a subject of satire as any other problematic historical figure. Given his outsized influence on our enforced morality laws, he should be. But the timing suggests that perhaps the security apparatus is feeling defensive, wounded by the recent judgment of treason against one of their own, and want to go back to a time where their name was sacrosanct.

The move is also part of a larger trend where state actors have begun to look at criticisms in places they didn’t police before. The Establishment’s anger and campaign against Dawn is the most obvious example. But the Karachi art biennale was similarly threatened when one of their pieces was considered “anti-state” (that it dealt with public domain information about a man accused of 444 murders didn’t matter as much) and also raided by people claiming to be from security institutions. Literary festivals have long since been self-censoring, knowing well that if they enjoy a begrudging tolerance, it, too, is balanced on someone else’s knife.

It’s a timely reminder for all of those who look to the arts to provide a “soft image” of Pakistan, a blindingly facile idea. Art isn’t meant to project a “soft image”. It’s not cheese. It is not Art’s duty to act as a country’s PR agent by projecting pretty images to gloss over darker cracks. Art is thinking made real, and the reason people around the world are interested in our cultural output is because its urgency, too, is very real here. These attacks on anything that gives Pakistan “a bad name” demonstrate the common fear that looms over any creative life in Pakistan: Do not shine too brightly or too far, less their eyes fall on you too. Our literature and art (such as they are) exist now as they have always existed, in code. Direct criticism is often implied but rarely declared, and any lapses in this are more likely the product of happy ignorance than studied tolerance.

Maybe you think this is all just a English-medium conspiracy theory. If you do I urge you to read A Case of Exploding Mangoes, a fiction about conspiracy theories set in a country where they mostly turn out to be true. Available now in Urdu as well – for a limited time only.

Write to thekantawala@gmail.com

Spoiler Alert: We don’t.

This week the book made headlines again because the offices of the local publishers of the novel were raided by men claiming to be from security institutions. In addition, General Zia’s son has issue a defamation suit for 1 billion rupees against them for “maligning the former ruler’s name”, years after he had presumably been told his father was the subject of a bestselling novel. The book has been readily available in Pakistan for years, so what changed? The language. It’s being published in Urdu. The raid and defamation notice are the clearest signs yet of exactly how the state values the danger of cultural products based on their intended audience.

English language novels (or articles, papers, channels, people) are generally ignored by the state for the same reasons that most of the ramblings in this column or contemporary art galleries or English newspapers don’t matter to them: the audience demographic is too small to matter, or else irrelevant. But Hanif’s work, himself brilliant in both Urdu and English, is different. Humour, particularly political humour, can cut through the pretensions of class and outlook with just a chuckle. Its the way stand-up comics enchant crowds of thousands. A shared laugh is a shared connection, and a shared laugh by readers at Zia’s expense in Urdu is clearly a much more threatening thing than a glowing New York Times review.

It is my hope that nothing will come of the harassment of the publishers or the defamation case. As a public domain figure General Zia is as appropriate as a subject of satire as any other problematic historical figure. Given his outsized influence on our enforced morality laws, he should be. But the timing suggests that perhaps the security apparatus is feeling defensive, wounded by the recent judgment of treason against one of their own, and want to go back to a time where their name was sacrosanct.

The move is also part of a larger trend where state actors have begun to look at criticisms in places they didn’t police before. The Establishment’s anger and campaign against Dawn is the most obvious example. But the Karachi art biennale was similarly threatened when one of their pieces was considered “anti-state” (that it dealt with public domain information about a man accused of 444 murders didn’t matter as much) and also raided by people claiming to be from security institutions. Literary festivals have long since been self-censoring, knowing well that if they enjoy a begrudging tolerance, it, too, is balanced on someone else’s knife.

These attacks on anything that gives Pakistan “a bad name” demonstrate the common fear that looms over any creative life in Pakistan: Do not shine too brightly or too far, less their eyes fall on you too

It’s a timely reminder for all of those who look to the arts to provide a “soft image” of Pakistan, a blindingly facile idea. Art isn’t meant to project a “soft image”. It’s not cheese. It is not Art’s duty to act as a country’s PR agent by projecting pretty images to gloss over darker cracks. Art is thinking made real, and the reason people around the world are interested in our cultural output is because its urgency, too, is very real here. These attacks on anything that gives Pakistan “a bad name” demonstrate the common fear that looms over any creative life in Pakistan: Do not shine too brightly or too far, less their eyes fall on you too. Our literature and art (such as they are) exist now as they have always existed, in code. Direct criticism is often implied but rarely declared, and any lapses in this are more likely the product of happy ignorance than studied tolerance.

Maybe you think this is all just a English-medium conspiracy theory. If you do I urge you to read A Case of Exploding Mangoes, a fiction about conspiracy theories set in a country where they mostly turn out to be true. Available now in Urdu as well – for a limited time only.

Write to thekantawala@gmail.com