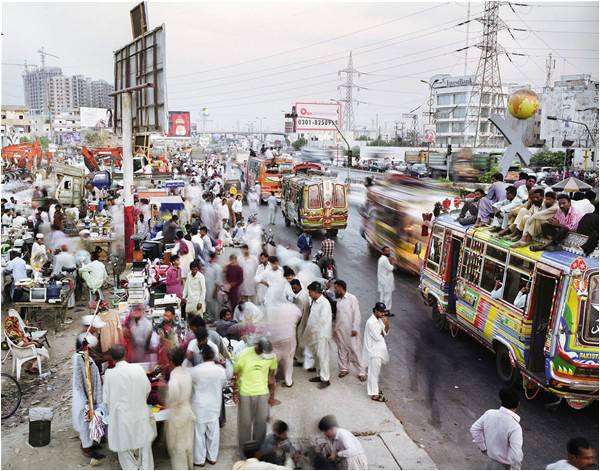

Pakistan’s economy has been in the news lately and for all the right reasons. The Wall Street Journal carried an article on Feb 1, trumpeting its growing middle class, implying that the substantial size of the domestic market and growing purchasing power should propel consumer spending and by extension GDP, to higher levels in the short to medium terms. On Feb 21, The Washington Post made the point that a double victory was in sight as Pakistan has not only made gains against terrorism but its economy is also on the march. On March 6, Dr. Shahid Javed Burki asserted in an op-ed piece in The Express Tribune that Pakistan’s GDP is under-estimated by, he surmises, about $70 billion, and is closer to $350 billion than the currently acknowledged $280 billion.

If Dr. Burki is right—and he claims that he has persuaded the finance minister to get help from the World Bank in overhauling the statistics, so we may hear startling news soon—then Pakistan’s per capita GDP will also increase by 25%, propelling it way up the rankings issued by institutions such as the World Bank and the World Economic Forum. Dr. Burki optimistically predicts that this will have a significant impact on investor confidence. The only surprising thing in his article is the impression he conveys of having to do some hard selling to persuade the current finance minister to set about revising the data collection machinery with World Bank help. One cannot imagine why any finance minister would refuse (free) technical assistance which would overnight succeed in raising average incomes by about a quarter.

These bullish analyses merit a closer look.

Let’s look at the thesis of a growing middle class in Pakistan pushing up consumer spending, and in the long term GDP (the WSJ article does not explicitly draw the link with GDP, but this much is pretty obvious for any student of Economics 101). The idea that Pakistan has a large and growing middle class has been gaining currency since 2011, when a prominent researcher at the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE), Dr Durr-e-Nayab, published a paper estimating the size of the middle class. Using a composite index featuring household expenditure data in addition to a range of non-income variables (level of education of head of household, ownership of consumer durables, availability of sanitation facilities to name a few), she found that 35% of Pakistan’s population can be considered middle class. This finding thrilled planners and policymakers, not least because it showed that Pakistan had trumped India in an economy-related field, with the estimated size of India’s middle class just 25%. This is almost precisely the figure that the WSJ article uses, by the way, postulating that with the middle and upper classes forming 38% of the population, Pakistan’s economy is about to take off, given the inevitable increase in demand for consumer durables.

What the WSJ reporter missed, however, is that the researcher who calculated the size of the middle class all that while ago, was at pains to point out that her classification of the middle class was not by income alone. In fact, she stressed the need to make a distinction between “middle-income” and “middle class.” In her classification, the 35% who fall in the middle class may or may not have the disposable income needed to generate a spurt in aggregate demand. Add to that the fact that the researcher was using a dataset (the 2007-08 Household Income and Expenditure Survey or HIES) which showed poverty in Pakistan at 17% (at a time when estimated poverty in the US was 15%), and it all starts to look a little less rosy.

Which brings us to the estimation of the GDP. There is little doubt that data gathering systems in Pakistan could probably do with a thorough overhaul. For example, there is no disputing Dr. Burki’s assertion that the urban population was probably underestimated in the last census (pioneering work by urban specialist Reza Ali has contributed enormously to this debate). People living in urban or urbanizing (a definition suggested by Mr. Ali) areas probably form more than half of the population, as compared to 30% as estimated in the last census.

Dr. Burki’s assertion that the surveys used to collect data on the services sector, particularly newly emerging areas such as domestic tourism, entertainment, and communications are in need of review is also credible. But the implication that they are going to add significantly to the GDP is questionable, given that they are relatively small components of a services sector dominated by retail and wholesale trade, and transport.

And while Pakistan’s data collection agencies may very well be underestimating output from a range of small enterprises and services, they do compensate in other areas. They have, for example, perfected the art of making livestock look like a key driver of growth. Their creativity is obvious from the fact that livestock typically is about 45% of the value added in agriculture (with major crops typically amounting to a third), but a look at the breakdown of income sources for rural households, as reported in the HIES, shows that income from livestock barely tops 15% of total household income. The point here is that while data collection is lagging for some sectors, it may very well be over-compensating in others. A rehaul of data collection mechanisms is probably long overdue and very much to be welcomed, but let’s not break out the mithai just yet—unless we adjust these imbalances before we draw conclusions, we may be in for some rude surprises.

The key lesson from this spate of articles is, however, how the news from Pakistan continues to maintain an emphasis on the achievement of high growth rates, regardless of human development outcomes. The emphasis on high growth is in turn the product of a history of unstable political environments, and the lack of certainty about the holding of general elections. Successive governments have to show quick results, primarily to impress the international community, rather than to roll up their sleeves and get their hands dirty with the more painstaking process of bringing about appreciable improvements in the standard of living of the ordinary people. Until it becomes more important to impute a value to the quality of basic public services, than to estimate value added in production, we will continue to mislead ourselves.

The writer is a researcher based in Islamabad.

If Dr. Burki is right—and he claims that he has persuaded the finance minister to get help from the World Bank in overhauling the statistics, so we may hear startling news soon—then Pakistan’s per capita GDP will also increase by 25%, propelling it way up the rankings issued by institutions such as the World Bank and the World Economic Forum. Dr. Burki optimistically predicts that this will have a significant impact on investor confidence. The only surprising thing in his article is the impression he conveys of having to do some hard selling to persuade the current finance minister to set about revising the data collection machinery with World Bank help. One cannot imagine why any finance minister would refuse (free) technical assistance which would overnight succeed in raising average incomes by about a quarter.

These bullish analyses merit a closer look.

Let’s look at the thesis of a growing middle class in Pakistan pushing up consumer spending, and in the long term GDP (the WSJ article does not explicitly draw the link with GDP, but this much is pretty obvious for any student of Economics 101). The idea that Pakistan has a large and growing middle class has been gaining currency since 2011, when a prominent researcher at the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE), Dr Durr-e-Nayab, published a paper estimating the size of the middle class. Using a composite index featuring household expenditure data in addition to a range of non-income variables (level of education of head of household, ownership of consumer durables, availability of sanitation facilities to name a few), she found that 35% of Pakistan’s population can be considered middle class. This finding thrilled planners and policymakers, not least because it showed that Pakistan had trumped India in an economy-related field, with the estimated size of India’s middle class just 25%. This is almost precisely the figure that the WSJ article uses, by the way, postulating that with the middle and upper classes forming 38% of the population, Pakistan’s economy is about to take off, given the inevitable increase in demand for consumer durables.

What the WSJ reporter missed is that the researcher who calculated the size of the middle class all that while ago, was at pains to point out that her classification of the middle class was not by income alone. She stressed

a distinction between "middle-income" and "middle class"

What the WSJ reporter missed, however, is that the researcher who calculated the size of the middle class all that while ago, was at pains to point out that her classification of the middle class was not by income alone. In fact, she stressed the need to make a distinction between “middle-income” and “middle class.” In her classification, the 35% who fall in the middle class may or may not have the disposable income needed to generate a spurt in aggregate demand. Add to that the fact that the researcher was using a dataset (the 2007-08 Household Income and Expenditure Survey or HIES) which showed poverty in Pakistan at 17% (at a time when estimated poverty in the US was 15%), and it all starts to look a little less rosy.

Which brings us to the estimation of the GDP. There is little doubt that data gathering systems in Pakistan could probably do with a thorough overhaul. For example, there is no disputing Dr. Burki’s assertion that the urban population was probably underestimated in the last census (pioneering work by urban specialist Reza Ali has contributed enormously to this debate). People living in urban or urbanizing (a definition suggested by Mr. Ali) areas probably form more than half of the population, as compared to 30% as estimated in the last census.

Dr. Burki’s assertion that the surveys used to collect data on the services sector, particularly newly emerging areas such as domestic tourism, entertainment, and communications are in need of review is also credible. But the implication that they are going to add significantly to the GDP is questionable, given that they are relatively small components of a services sector dominated by retail and wholesale trade, and transport.

And while Pakistan’s data collection agencies may very well be underestimating output from a range of small enterprises and services, they do compensate in other areas. They have, for example, perfected the art of making livestock look like a key driver of growth. Their creativity is obvious from the fact that livestock typically is about 45% of the value added in agriculture (with major crops typically amounting to a third), but a look at the breakdown of income sources for rural households, as reported in the HIES, shows that income from livestock barely tops 15% of total household income. The point here is that while data collection is lagging for some sectors, it may very well be over-compensating in others. A rehaul of data collection mechanisms is probably long overdue and very much to be welcomed, but let’s not break out the mithai just yet—unless we adjust these imbalances before we draw conclusions, we may be in for some rude surprises.

The key lesson from this spate of articles is, however, how the news from Pakistan continues to maintain an emphasis on the achievement of high growth rates, regardless of human development outcomes. The emphasis on high growth is in turn the product of a history of unstable political environments, and the lack of certainty about the holding of general elections. Successive governments have to show quick results, primarily to impress the international community, rather than to roll up their sleeves and get their hands dirty with the more painstaking process of bringing about appreciable improvements in the standard of living of the ordinary people. Until it becomes more important to impute a value to the quality of basic public services, than to estimate value added in production, we will continue to mislead ourselves.

The writer is a researcher based in Islamabad.