It is hard to write about Nigar – hard to decide which thread of her life to pick up, and which to let go – harder still with only a handful of words in which to do it. So where to begin?

At her core, Nigar was a person of strong passions and great loyalties for places and people. Born and raised in Lahore, she soon discovered her first love – the Convent of Jesus and Mary, where the ethical parameters of her life were shaped and some of her deepest friendships forged. Her second love – which, if it did not quite dislodge the first, certainly superseded it – was Government College Lahore, which she joined as an undergraduate student and left after completing her Masters in Economics. Actively embroiled in college life, she was a member of the Government College Dramatics Club and later editor of the Ravi. As her assistant editor (or ‘chotta’), Samina Rahman recalls that she has never been scolded so much by anyone than she was by Nigar during this time; she also remembers the hard work put in by Nigar and the meticulous attention paid to each detail at every stage of the editorial process. From GC the next step was to New Hall, Cambridge, on a Commonwealth scholarship; then back to Pakistan, and Quaid-e-Azam University, where she taught Economics for nearly sixteen years; the setting up of the Women Action Forum’s (WAF) Islamabad Chapter, and a lifelong involvement in the women’s movement.

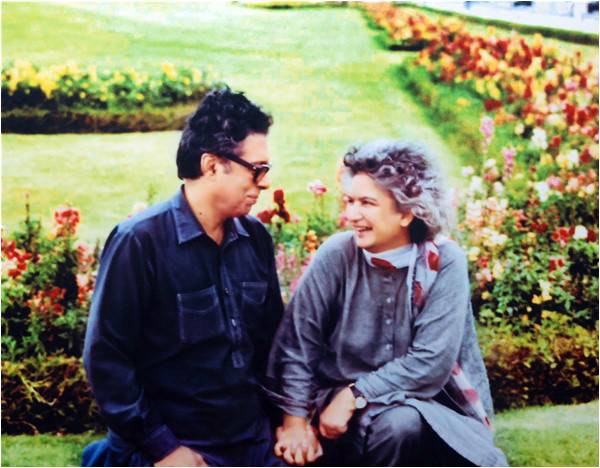

Nigar was fuelled by a zest for life and an impatience with time honoured taboos and restrictions. As long as she was clear in her own mind about what she was doing, she was truly indifferent to society’s opinion. This quality not only enabled her to enjoy life on her own terms, it also expanded the boundaries for others to come. Thus, despite loud protests from male faculty and friends, she was the first woman to breach the male bastion of the GC-Islamia College cricket match, which she attended and thoroughly enjoyed. So too her marriage. Her parents, Riazuddin Ahmad and Akhtar (‘Akhan Apa’) were in Romania on a government posting when she and Tariq Siddiqi – a similarly nonconformist civil servant, who had at the time been dismissed from service for impertinence to the powers-that-be – discovered each other. The marriage took place not in Islamabad where they lived at that time, but at a sufi shrine adjacent to a spring at Dum Torh in Swat. Her sister Munna and Nighat Said made up the bride’s party, and two of Tariq’s friends were the baraat. The bride wore a freshly washed and ironed red khaddar jora, and the nikah was witnessed by two women. About her life with Tariq, I will only say that they were happy together, and the most doting of parents to Bilal and Ahmad, and daughter-in-law Kate, and that their children have shown that unstinting love shaped by the principles of humanity and compassion is perhaps the best recipe for good children.

Set up in 1985, Aurat Foundation was Nigar’s brainchild – hers and Shahla Zia’s, lawyer and activist. Under their guidance, Aurat grew from a small information center into a national organisation. The facilitation of grassroots women’s entry into the political and economic mainstream was one of its important achievements. Shelly’s untimely death in 2005 put an end to their partnership. Nigar never reconciled herself to this loss, but it did not lessen her commitment either to Aurat, or to her dream of a just society.

Nigar passed away on the evening of February 23 2017, seven days after completing the seventy-two years of the life that was given her. Of these, almost twenty were spent in battling Parkinson’s – a cruel illness that slowly made her a stranger to her own body. Normally, in such cases, the loss that death brings is tempered by the knowledge that the suffering too has ended. It has been different with Nigar. The timeworn platitudes bring no relief – only a bewilderment where rationality wars with emotion and denies houseroom to clichés and common sense. Perhaps this is because Nigar herself never turned her face away from life – or let go of her sense of the ridiculous in the face of pain and the body’s recalcitrance, when each small routine task was a battle to be waged and won. Perhaps that is why, as we sit here today – the friends who loved her and whose lives she touched – and look back on her life, all that we can recall is the laughter; the energy, the enjoyment of absurdity, the taken for granted mutuality of caring and support, the small pleasures - the sharing of ideas, the arguments and disagreements; the dreams she dreamed and the single minded intensity with which she pursued them – often to the point of exasperation. As Nighat Said remarked only recently – “she could be a pain in the neck!”

Despite her body’s betrayal, Nigar kept faith with the ideals that had shaped her life and never lost touch with the larger politics of the world around her. Months before her death – not the last time we met, but certainly the last time we found the time to talk to each other – she expressed her unhappiness with the depoliticisation of NGOs, the growing consumerist ethic, and the loss of old values. “We must do something about it”, she had said. “We need to get together, plan and find ways of fighting for what we believe in”. I remember looking at her and thinking – this is not a rhetorical statement; she means what she is saying. Recalling that evening – her indifference to the constraints of her illness; her courage and her commitment to the ideals she believed in, I grieve at her loss but my heart refuses to mourn Nigar.

At her core, Nigar was a person of strong passions and great loyalties for places and people. Born and raised in Lahore, she soon discovered her first love – the Convent of Jesus and Mary, where the ethical parameters of her life were shaped and some of her deepest friendships forged. Her second love – which, if it did not quite dislodge the first, certainly superseded it – was Government College Lahore, which she joined as an undergraduate student and left after completing her Masters in Economics. Actively embroiled in college life, she was a member of the Government College Dramatics Club and later editor of the Ravi. As her assistant editor (or ‘chotta’), Samina Rahman recalls that she has never been scolded so much by anyone than she was by Nigar during this time; she also remembers the hard work put in by Nigar and the meticulous attention paid to each detail at every stage of the editorial process. From GC the next step was to New Hall, Cambridge, on a Commonwealth scholarship; then back to Pakistan, and Quaid-e-Azam University, where she taught Economics for nearly sixteen years; the setting up of the Women Action Forum’s (WAF) Islamabad Chapter, and a lifelong involvement in the women’s movement.

Despite her body's betrayal, Nigar kept faith with the ideals that had shaped her life and never lost touch with the larger politics of the world around her. Months before her death … she expressed her unhappiness with the depoliticisation of NGOs, the growing consumerist ethic, and the loss of old values. "We must do something about it", she had said. "We need to get together, plan and find ways of fighting for what we believe in". I remember looking at her and thinking - this is not a rhetorical statement; she means what she is saying

Nigar was fuelled by a zest for life and an impatience with time honoured taboos and restrictions. As long as she was clear in her own mind about what she was doing, she was truly indifferent to society’s opinion. This quality not only enabled her to enjoy life on her own terms, it also expanded the boundaries for others to come. Thus, despite loud protests from male faculty and friends, she was the first woman to breach the male bastion of the GC-Islamia College cricket match, which she attended and thoroughly enjoyed. So too her marriage. Her parents, Riazuddin Ahmad and Akhtar (‘Akhan Apa’) were in Romania on a government posting when she and Tariq Siddiqi – a similarly nonconformist civil servant, who had at the time been dismissed from service for impertinence to the powers-that-be – discovered each other. The marriage took place not in Islamabad where they lived at that time, but at a sufi shrine adjacent to a spring at Dum Torh in Swat. Her sister Munna and Nighat Said made up the bride’s party, and two of Tariq’s friends were the baraat. The bride wore a freshly washed and ironed red khaddar jora, and the nikah was witnessed by two women. About her life with Tariq, I will only say that they were happy together, and the most doting of parents to Bilal and Ahmad, and daughter-in-law Kate, and that their children have shown that unstinting love shaped by the principles of humanity and compassion is perhaps the best recipe for good children.

Set up in 1985, Aurat Foundation was Nigar’s brainchild – hers and Shahla Zia’s, lawyer and activist. Under their guidance, Aurat grew from a small information center into a national organisation. The facilitation of grassroots women’s entry into the political and economic mainstream was one of its important achievements. Shelly’s untimely death in 2005 put an end to their partnership. Nigar never reconciled herself to this loss, but it did not lessen her commitment either to Aurat, or to her dream of a just society.

Nigar passed away on the evening of February 23 2017, seven days after completing the seventy-two years of the life that was given her. Of these, almost twenty were spent in battling Parkinson’s – a cruel illness that slowly made her a stranger to her own body. Normally, in such cases, the loss that death brings is tempered by the knowledge that the suffering too has ended. It has been different with Nigar. The timeworn platitudes bring no relief – only a bewilderment where rationality wars with emotion and denies houseroom to clichés and common sense. Perhaps this is because Nigar herself never turned her face away from life – or let go of her sense of the ridiculous in the face of pain and the body’s recalcitrance, when each small routine task was a battle to be waged and won. Perhaps that is why, as we sit here today – the friends who loved her and whose lives she touched – and look back on her life, all that we can recall is the laughter; the energy, the enjoyment of absurdity, the taken for granted mutuality of caring and support, the small pleasures - the sharing of ideas, the arguments and disagreements; the dreams she dreamed and the single minded intensity with which she pursued them – often to the point of exasperation. As Nighat Said remarked only recently – “she could be a pain in the neck!”

Despite her body’s betrayal, Nigar kept faith with the ideals that had shaped her life and never lost touch with the larger politics of the world around her. Months before her death – not the last time we met, but certainly the last time we found the time to talk to each other – she expressed her unhappiness with the depoliticisation of NGOs, the growing consumerist ethic, and the loss of old values. “We must do something about it”, she had said. “We need to get together, plan and find ways of fighting for what we believe in”. I remember looking at her and thinking – this is not a rhetorical statement; she means what she is saying. Recalling that evening – her indifference to the constraints of her illness; her courage and her commitment to the ideals she believed in, I grieve at her loss but my heart refuses to mourn Nigar.