Mussawari Siddiqui was the founding vice-principal of the Overseas Pakistanis Foundation Girls’ College in Islamabad. She passed away on January 15, 2017 (born 1931) leaving behind the legacy of a world class institution that serves the daughters of Pakistanis who work overseas. Mussawari made this college into a model residential institution which not only provided a safe space for young women whose parents were abroad, but in addition the quality of education here was exemplary as it also groomed young women for a career in the future. This was a secular space that reinforced the values of a South Asian Muslim society where personal responsibility, academic excellence and physical education were foremost. These young women were home makers par excellence. The college awarded a bachelor’s degree and was later upgraded to a postgraduate institution. Mussawari worked hard for twenty years (1985-2005) at the OPF Girls’ College to give it the stature that it has today. Rabia Noor, the founding principal of the college, invited her to work at this college after Mussawari’s long service to the Cantonment Board Girls School in Lalkurti-Tariqabad and later as principal of the Army Public School in Taxila. If one were to speak of an icon for women’s education in Pakistan, then Mussawari Siddiqui’s name tops the list.

Mussawari started her educator’s career as the principal of the CB Girls School in Lalkurti-Tariqabad, a neighborhood of low-income, grassroots workers: painters, carpenters, tailors, mechanics, day labourers, drug addicts and domestic maids and the women buffalo herds who kept their animals in the neighbourhood and sold milk to the locals in the area. It was their daughters that Mussawari educated for four decades when she retired and took up her position as the principal of the Army Public School in Taxila; she commuted fifty miles daily to Taxila from Rawalpindi and enjoyed the drive as well as the position. It was after this that she became vice-principal of the OPF Girls’ College in Islamabad.

On her first day as principal of the Lalkurti-Tariqabad school, Mussawari wept. During an inspection, she found that the place didn’t even have a toilet, let alone a library. The school building was a ruin. Instead of a refusal to accept the principal’s position, Mussawari took on the challenge. She built the school. She created a library, personally chose the books and spent hours there. She read to the students and encouraged them to read. Mussawari’s matriculation results were outstanding for years as her students achieved the highest scores in the district. She developed the sports department and made sports compulsory for every student. Her girls went to competitions with other schools in the district and brought back shields and trophies for their distinguished performance. During General Zia-ul-Haq’s rule, her school was awarded the honour twice for being the best cantonment school. Mussawari additionally received the award as the best principal in the cantonment school system.

Mussawari was not only a model school teacher and mentor, she was also an excellent sportswoman herself, with an amazing energy that impacted her students. She played netball and volley ball with her students. While she excelled in her skills as a teacher and mentor, Mussawari also learned to drive, which was unusual for women in her time. She was the third woman in Rawalpindi city to pass the driving test that let her have a driver’s license.

I met Mussawari Siddiqui in 1969 after I came back from England with my master’s degree in

English. Mussawari was at that time the principal of the girls’ high school in Lalkurti-Tariqabad. We immediately struck up a friendship. Pakistan was a secular society at the time and we women wore our dhobi-starched cotton saris to work. We both drove our own cars. At the time in 1969 only a handful of people owned cars and one could tell whose car it was when it drove past on the Mall Road in Rawalpindi Cantonment or any other place in the city. As for a woman driver, hardly any were around - except my mother amongst us.

The party at which I met Mussawri was a celebration of my successful return from England.

What bonded us together were our immigrant histories from the Partition of India and the creation of the Pakistani state in 1947. We were all Urdu-speakers though my mother was from Lahore. My father, too, was a Burney from Buland Shahr in India but we were not related to Ilyas Burney. Mussawari and her husband too were migrants from India. Mussawari got married at the age of seventeen in India and the couple moved to Pakistan immediately after

Partition. Aftab Siddiqui’s first posting was in Sargodha. At the time they only had a daughter, Tabbasum who sadly died as an infant. This was a painful period for the couple as Aftab Siddiqui did not keep good health - in addition to the fact that they could not provide the best medical care for Tabbasum.

Mussawari Siddiqui was the post-Partition career woman, who not only educated herself whilst she raised her family, but also worked with a passion to support other young women’s education. While Aftab Siddiqui was posted in Kasur, Mussawari studied for her college education: first she completed the higher secondary school certificate (FA) and later she got a Bachelor’s in education from the Lady Maclagan College in Lahore. Mussawari travelled daily from Kasur to Lahore to attend the Lady Maclagan College. At 4 a.m. in the morning she walked to the river Ravi/Chenab, woke up the boatman who rowed her across the river where she got off to walk a long distance to get to Samanabad. From Samanabad she rode the bus to Lady MacLagan. This was a dangerous journey until Aftab Siddiqui found in her diary a note that gave her address and telephone number should anything happen to her. He immediately moved the family to Lahore in a small rental house where he hired a maid to help Mussawari with the children and her education. He himself stayed in Kasur to continue his work.

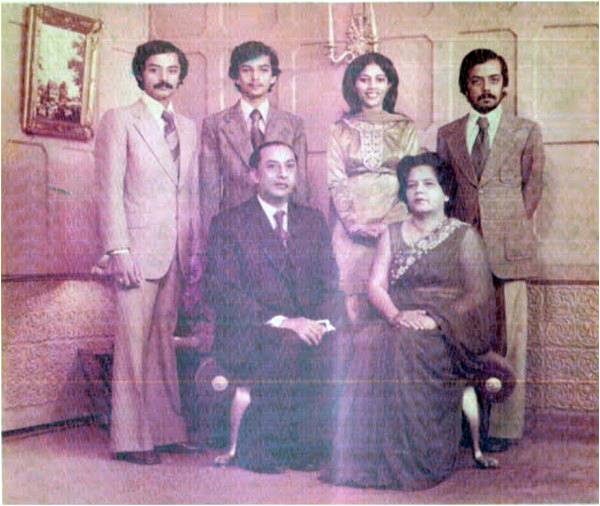

Mussawari’s most distinguished record is as vice-principal of the Overseas Pakistanis Foundation College for Girls in Islamabad. It was while she worked here and while I worked for the Open University in Islamabad that the two of us became real close. With her usual grace, Mussawari always provided hospitality and we would also spend long hours to talk, as we lay on the rug in her living room. Our conversations were about our country, our work and our lives as single women: we lived in a society dominated by men. While I studied for a PhD in the United States, Mussawari sadly lost her husband and with that, for a long time, she also lost her humour. But she eventually got back on her feet and gave all of herself to her students at OPF. She retired from OPF in 2005 and moved to Karachi to be with her children Imrana Zuhair Siddiqui and Tariq. Her two other sons, Kamran and Azfar, both physicians, work in England and the United States respectively. Imrana, like her mother, is an educator with a postgraduate degree from England.

Mussawari was the author of an excellent Urdu novel, Namood-e-Sehr that is the story of two Muslim families that migrated to East Pakistan from Bihar, immediately after the 1947 Partition.

I’ll always miss Mussawari. She was a true Gandhian woman, who lived to serve. She took care of my house for eight years while I was in the United States to rebuild my life after a blasphemy fatwa on me from the state establishment at the Open University.

We mourn you. Sleep in peace, dear friend.

Shemeem Burney Abbas is currently Associate Professor of Political Science, Gender Studies and Literature at The State University of New York at Purchase. She is the author of Pakistan’s Blasphemy Laws: From Islamic Empires to the Taliban and The Female Voice in Sufi Ritual: Devotional Practices of Pakistan and India. Additionally, Imrana Zuhair Siddiqui provided biographical details and photos of her mother’s life for this article

Mussawari started her educator’s career as the principal of the CB Girls School in Lalkurti-Tariqabad, a neighborhood of low-income, grassroots workers: painters, carpenters, tailors, mechanics, day labourers, drug addicts and domestic maids and the women buffalo herds who kept their animals in the neighbourhood and sold milk to the locals in the area. It was their daughters that Mussawari educated for four decades when she retired and took up her position as the principal of the Army Public School in Taxila; she commuted fifty miles daily to Taxila from Rawalpindi and enjoyed the drive as well as the position. It was after this that she became vice-principal of the OPF Girls’ College in Islamabad.

Mussawari was a true Gandhian woman who lived to serve

On her first day as principal of the Lalkurti-Tariqabad school, Mussawari wept. During an inspection, she found that the place didn’t even have a toilet, let alone a library. The school building was a ruin. Instead of a refusal to accept the principal’s position, Mussawari took on the challenge. She built the school. She created a library, personally chose the books and spent hours there. She read to the students and encouraged them to read. Mussawari’s matriculation results were outstanding for years as her students achieved the highest scores in the district. She developed the sports department and made sports compulsory for every student. Her girls went to competitions with other schools in the district and brought back shields and trophies for their distinguished performance. During General Zia-ul-Haq’s rule, her school was awarded the honour twice for being the best cantonment school. Mussawari additionally received the award as the best principal in the cantonment school system.

Mussawari was not only a model school teacher and mentor, she was also an excellent sportswoman herself, with an amazing energy that impacted her students. She played netball and volley ball with her students. While she excelled in her skills as a teacher and mentor, Mussawari also learned to drive, which was unusual for women in her time. She was the third woman in Rawalpindi city to pass the driving test that let her have a driver’s license.

I met Mussawari Siddiqui in 1969 after I came back from England with my master’s degree in

English. Mussawari was at that time the principal of the girls’ high school in Lalkurti-Tariqabad. We immediately struck up a friendship. Pakistan was a secular society at the time and we women wore our dhobi-starched cotton saris to work. We both drove our own cars. At the time in 1969 only a handful of people owned cars and one could tell whose car it was when it drove past on the Mall Road in Rawalpindi Cantonment or any other place in the city. As for a woman driver, hardly any were around - except my mother amongst us.

The party at which I met Mussawri was a celebration of my successful return from England.

What bonded us together were our immigrant histories from the Partition of India and the creation of the Pakistani state in 1947. We were all Urdu-speakers though my mother was from Lahore. My father, too, was a Burney from Buland Shahr in India but we were not related to Ilyas Burney. Mussawari and her husband too were migrants from India. Mussawari got married at the age of seventeen in India and the couple moved to Pakistan immediately after

Partition. Aftab Siddiqui’s first posting was in Sargodha. At the time they only had a daughter, Tabbasum who sadly died as an infant. This was a painful period for the couple as Aftab Siddiqui did not keep good health - in addition to the fact that they could not provide the best medical care for Tabbasum.

Mussawari Siddiqui was the post-Partition career woman, who not only educated herself whilst she raised her family, but also worked with a passion to support other young women’s education. While Aftab Siddiqui was posted in Kasur, Mussawari studied for her college education: first she completed the higher secondary school certificate (FA) and later she got a Bachelor’s in education from the Lady Maclagan College in Lahore. Mussawari travelled daily from Kasur to Lahore to attend the Lady Maclagan College. At 4 a.m. in the morning she walked to the river Ravi/Chenab, woke up the boatman who rowed her across the river where she got off to walk a long distance to get to Samanabad. From Samanabad she rode the bus to Lady MacLagan. This was a dangerous journey until Aftab Siddiqui found in her diary a note that gave her address and telephone number should anything happen to her. He immediately moved the family to Lahore in a small rental house where he hired a maid to help Mussawari with the children and her education. He himself stayed in Kasur to continue his work.

Mussawari’s most distinguished record is as vice-principal of the Overseas Pakistanis Foundation College for Girls in Islamabad. It was while she worked here and while I worked for the Open University in Islamabad that the two of us became real close. With her usual grace, Mussawari always provided hospitality and we would also spend long hours to talk, as we lay on the rug in her living room. Our conversations were about our country, our work and our lives as single women: we lived in a society dominated by men. While I studied for a PhD in the United States, Mussawari sadly lost her husband and with that, for a long time, she also lost her humour. But she eventually got back on her feet and gave all of herself to her students at OPF. She retired from OPF in 2005 and moved to Karachi to be with her children Imrana Zuhair Siddiqui and Tariq. Her two other sons, Kamran and Azfar, both physicians, work in England and the United States respectively. Imrana, like her mother, is an educator with a postgraduate degree from England.

Mussawari was the author of an excellent Urdu novel, Namood-e-Sehr that is the story of two Muslim families that migrated to East Pakistan from Bihar, immediately after the 1947 Partition.

I’ll always miss Mussawari. She was a true Gandhian woman, who lived to serve. She took care of my house for eight years while I was in the United States to rebuild my life after a blasphemy fatwa on me from the state establishment at the Open University.

We mourn you. Sleep in peace, dear friend.

Shemeem Burney Abbas is currently Associate Professor of Political Science, Gender Studies and Literature at The State University of New York at Purchase. She is the author of Pakistan’s Blasphemy Laws: From Islamic Empires to the Taliban and The Female Voice in Sufi Ritual: Devotional Practices of Pakistan and India. Additionally, Imrana Zuhair Siddiqui provided biographical details and photos of her mother’s life for this article