The first part of this article described the massacre of Muslims in August 1947 in Rupnagar, East Punjab. In this second part, we have the account of another massacre as extracted from the book titled Divide and Quit, written by Sir Penderel Moon.

Sir Moon, a well-respected British civil servant and author of several books served in various senior administrative and staff appointments. He was employed during 1947 as minister for revenue by the State of Bahawalpur, South Punjab. In that capacity, he organised the exodus of Hindus and Sikhs from his State to India.

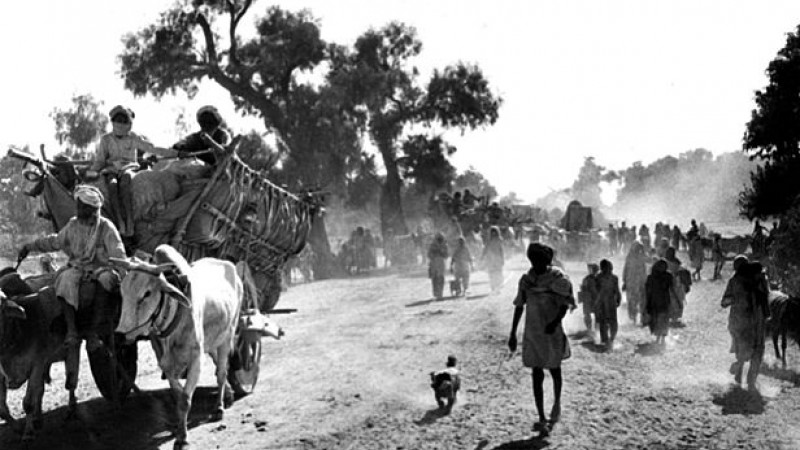

The population of Sikhs in the Bahawalpur State in 1947 was 50,000 and of the Hindus 190,000. The residents of the state were broadly categorised as “riasti” (meaning that they had lived there for generations) and non-riasti (implying recent settlers). This division was the result of constructing irrigation systems on the left bank of the Sutlej River. In the 1920s, the British administration created the Sutlej Valley Project that included development of four barrages and accompanying canals. These included the Firozpur, Islam, Sulemanki and Panjnad headworks. Nearly three million acres of land in Bahawalpur alone was irrigated. To bring this land under cultivation, a large number of Muslim and Sikh Jats from east Punjab were brought to the state with their families, cattle and implements. These people were experienced and efficient farmers who worked very hard to break the virgin land and make it yield large quantities of wheat, cotton and sugarcane.

Sikh farmers were, for most part, concentrated in the northeastern part of the state, near its border with the State of Bikaner. They also had recent ties with their original villages and were able to move across early without much loss of life, though a few of their isolated villages were brutally targeted. The non-Muslims of Bahawalpur and eastern towns, too, were transported by trains to India with only isolated incidents of violence.

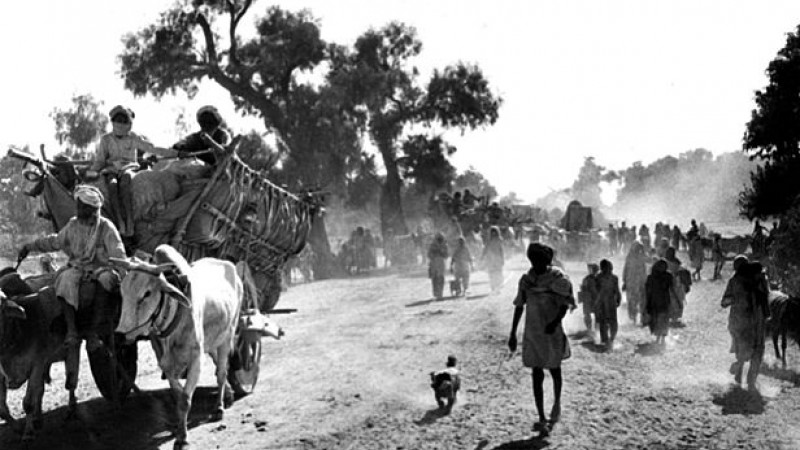

Rahim Yar Khan district had about 2,000 Sikhs, including women and children, who all wanted to migrate to India. However, due to a large desert on its east, the town is at a large distance from the Indian border by road or train. Although the railway line passed through the city, the shortest train track to Fazilka, the first railway station in India, via Samasatta, Bahawalpur, Hasilpur, Chishtian and Bahawalnagar, was 400 kilometers. The route was vulnerable to raids by marauding groups. In Bahawalpur, as in the rest of Punjab, the Muslims had nourished a strong anti-Sikh sentiment. The state administration, with the approval of Premier Mushtaq Gurmani, who later became Federal Interior Minister and the first Governor of West Pakistan, and under the supervision of Minister for Revenue Sir Moon, decided to send the Sikhs to India on foot. The Jaisalmer border on a direct march is 70 km away, with first 40 km through cultivated land and the remaining 30 km through desert where there were well-marked walking tracks. The first inhabited village on the Indian side is Chauki Kishengarh, a further 20 km away. The state government decided to provide camels and donkeys for old-men, women and children. It was expected that though the weather was still hot, the march through the desert, with adequate arrangements, would take a day or two. An escort of the Bahawalpur military under a Lt. Colonel was accompanied by an assistant commissioner with magisterial power – so as to guard the migrants against any betrayal by the military escort.

The Sikhs marched out under escort, but it proved to be a horrible tale of treachery and violence.

At the outset of the walk, they were persuaded to disarm. The column, well over 2,000 strong, set off in the afternoon of September 26th from a village near Rahim Yar Khan. On the first evening, when the column had encamped for the night, the escorting troops began to search the convoy for valuables. A certain Karnail Singh resisted, resulting in a fight. That led to the death of several Sikhs including Karnail Singh and injuries to several others. There was a great outcry in the camp. Rahim Yar Khan was still close and the Commanding Officer (CO) feared that some of the Sikhs might go back to report the incident to the civil administration. The Assistant Commissioner accompanying the column, too, talked of sending in a report but was persuaded to desist. The Sikhs now had little trust in the CO but he expressed regret and promised that it wouldn’t happen again.

The Sikhs journeyed on, reaching the end of the cultivated area by the evening, for their second night in the open. They had now reached the farthest limit of the cultivated area and would start their trek across the open desert without sufficient food and water. Here, with no hope of further contact with any authority, the CO shed whatever cloak of morality he was wearing. He demanded that the migrants should hand over all their belongings to the troops. He took the plea that as the Muslim immigrants from India had been relieved of all their belongings by Hindus and Sikhs, the Sikh migrants must also depart without their possessions. The Sikhs were now too helpless to resist. Their belongings were loaded onto military lorries and driven off.

The Sikhs journeyed on, reaching the end of the cultivated area by the evening, for their second night in the open. They had now reached the farthest limit of the cultivated area and would start their trek across the open desert without sufficient food and water. Here, with no hope of further contact with any authority, the CO shed whatever cloak of morality he was wearing. He demanded that the migrants should hand over all their belongings to the troops. He took the plea that as the Muslim immigrants from India had been relieved of all their belongings by Hindus and Sikhs, the Sikh migrants must also depart without their possessions. The Sikhs were now too helpless to resist. Their belongings were loaded onto military lorries and driven off.

The column then marched for two days under difficult conditions without any further incident. The border was 3 km away when they halted for the night on September 30. The migrants, perhaps, would have heaved a sigh of relief having come within a stone’s throw of asylum. However, unbeknown to the migrants, the CO had laid a sinister snare for them which would be sprung that night. They were now without help and at a very remote location. It would be days before their fate would be known to anyone.

A little after midnight, the two leaders of the Sikh column, Bakhtawar Singh and Bhag Singh, were roused from their slumber and told that they must get ready to start walking immediately. They protested and expressed their suspicion at being suddenly ordered to march at the dead of night. By way of answer, the CO had them bayoneted and killed. The rest of the column was gathered and moved off, but after they had gone a short distance, firing was heard ahead and they were ordered to halt. They were told that the firing was coming from a gang of armed Hurs, who were waiting in ambush. This was, of course, all a hoax. The CO had sent a few of his own men ahead who, as planned, were firing in the direction of the column.

On the pretext of an imminent attack by Hurs, the young women were separated under threat of violence and distributed among the sepoys. Having secured their loot and prey, the troops were anxious to get rid of men, old women and children. They were thus told to make a run for the border. At the same time, the escort began firing their rifles indiscriminately. Some of the Sikhs ran wildly forward in the direction of the border while the rest struggled after them. The troops from behind and those in hiding kept up a steady fire.

In the darkness and confusion, scores of stragglers were killed or wounded. At the time, it was impossible to tell if any of the column had survived. A few years later, when Sir Moon came in contact with some members of the ill-fated expedition, he learnt that a good many were able to reach Chauki Kishangarh safely. Camels were then sent out from there to the scene of the firing to bring in the wounded, most of whom were ultimately transported to Jodhpur and admitted to the hospital there. Sir Moon estimated that about 6-700 of the migrants survived the ambush. Sadly, nearly 1,300 lost their lives.

The presence of kidnapped women in Rahim Yar Khan could not be concealed and a whispering campaign spread in the city. A number of these women escaped from their captors and hid themselves in the tall standing crops just outside the town. There followed a regular game of hide-and-seek. In broad daylight, soldiers of the Bahawalpur Army were seen hunting these young women from one millet field to another. Some of them were recaptured, while others got away altogether, and were given shelter in various houses in the town. The respectable inhabitants of the city were greatly enraged and reported the presence of abducted women to the police. In the course of the year, all the women except 27 were recovered and repatriated to India.

When this story of coldblooded and treacherous murder came to the notice of the state authorities, they instituted an inquiry and arrested the CO. A few days later, however, he escaped to Multan, certainly with the connivance of his military guards. He crossed the Sutlej to Multan, beyond the jurisdiction of Bahawalpur.

This story of treacherous murder of innocent people is similar to the fate that befell Muslim migrants, as described in the first part of this article. As such, these two tales represent the calamity that Punjab went through at the hands of its own people.

Both sides indulged in the genocide. Khushwant Singh noted in his novel Train to Pakistan,

“The fact is, both sides killed. Both shot and stabbed and speared and clubbed. Both tortured. Both raped.”

To be fair, the main national leaders including Mahatma Gandhi-ji, the Quaid-e-Azam and Pandit Nehru never encouraged violence and asked their followers to stay calm and peaceful. However, the central leadership had lost control over masses. The command of streets had gone in the hands of armed goons, militant politicians, renegade security officials and fanatic religious leaders. Humanity suffered.

The Partition massacres were a sad episode in the history of the Subcontinent, and one of the greatest tragedies that mankind has ever known.

Sir Moon, a well-respected British civil servant and author of several books served in various senior administrative and staff appointments. He was employed during 1947 as minister for revenue by the State of Bahawalpur, South Punjab. In that capacity, he organised the exodus of Hindus and Sikhs from his State to India.

The population of Sikhs in the Bahawalpur State in 1947 was 50,000 and of the Hindus 190,000. The residents of the state were broadly categorised as “riasti” (meaning that they had lived there for generations) and non-riasti (implying recent settlers). This division was the result of constructing irrigation systems on the left bank of the Sutlej River. In the 1920s, the British administration created the Sutlej Valley Project that included development of four barrages and accompanying canals. These included the Firozpur, Islam, Sulemanki and Panjnad headworks. Nearly three million acres of land in Bahawalpur alone was irrigated. To bring this land under cultivation, a large number of Muslim and Sikh Jats from east Punjab were brought to the state with their families, cattle and implements. These people were experienced and efficient farmers who worked very hard to break the virgin land and make it yield large quantities of wheat, cotton and sugarcane.

Sikh farmers were, for most part, concentrated in the northeastern part of the state, near its border with the State of Bikaner. They also had recent ties with their original villages and were able to move across early without much loss of life, though a few of their isolated villages were brutally targeted. The non-Muslims of Bahawalpur and eastern towns, too, were transported by trains to India with only isolated incidents of violence.

They had now reached the farthest limit of the cultivated area and would start their trek across the open desert without sufficient food and water. Here, with no hope of further contact with any authority, the CO shed whatever cloak of morality he was wearing

Rahim Yar Khan district had about 2,000 Sikhs, including women and children, who all wanted to migrate to India. However, due to a large desert on its east, the town is at a large distance from the Indian border by road or train. Although the railway line passed through the city, the shortest train track to Fazilka, the first railway station in India, via Samasatta, Bahawalpur, Hasilpur, Chishtian and Bahawalnagar, was 400 kilometers. The route was vulnerable to raids by marauding groups. In Bahawalpur, as in the rest of Punjab, the Muslims had nourished a strong anti-Sikh sentiment. The state administration, with the approval of Premier Mushtaq Gurmani, who later became Federal Interior Minister and the first Governor of West Pakistan, and under the supervision of Minister for Revenue Sir Moon, decided to send the Sikhs to India on foot. The Jaisalmer border on a direct march is 70 km away, with first 40 km through cultivated land and the remaining 30 km through desert where there were well-marked walking tracks. The first inhabited village on the Indian side is Chauki Kishengarh, a further 20 km away. The state government decided to provide camels and donkeys for old-men, women and children. It was expected that though the weather was still hot, the march through the desert, with adequate arrangements, would take a day or two. An escort of the Bahawalpur military under a Lt. Colonel was accompanied by an assistant commissioner with magisterial power – so as to guard the migrants against any betrayal by the military escort.

The Sikhs marched out under escort, but it proved to be a horrible tale of treachery and violence.

At the outset of the walk, they were persuaded to disarm. The column, well over 2,000 strong, set off in the afternoon of September 26th from a village near Rahim Yar Khan. On the first evening, when the column had encamped for the night, the escorting troops began to search the convoy for valuables. A certain Karnail Singh resisted, resulting in a fight. That led to the death of several Sikhs including Karnail Singh and injuries to several others. There was a great outcry in the camp. Rahim Yar Khan was still close and the Commanding Officer (CO) feared that some of the Sikhs might go back to report the incident to the civil administration. The Assistant Commissioner accompanying the column, too, talked of sending in a report but was persuaded to desist. The Sikhs now had little trust in the CO but he expressed regret and promised that it wouldn’t happen again.

The Sikhs journeyed on, reaching the end of the cultivated area by the evening, for their second night in the open. They had now reached the farthest limit of the cultivated area and would start their trek across the open desert without sufficient food and water. Here, with no hope of further contact with any authority, the CO shed whatever cloak of morality he was wearing. He demanded that the migrants should hand over all their belongings to the troops. He took the plea that as the Muslim immigrants from India had been relieved of all their belongings by Hindus and Sikhs, the Sikh migrants must also depart without their possessions. The Sikhs were now too helpless to resist. Their belongings were loaded onto military lorries and driven off.

The Sikhs journeyed on, reaching the end of the cultivated area by the evening, for their second night in the open. They had now reached the farthest limit of the cultivated area and would start their trek across the open desert without sufficient food and water. Here, with no hope of further contact with any authority, the CO shed whatever cloak of morality he was wearing. He demanded that the migrants should hand over all their belongings to the troops. He took the plea that as the Muslim immigrants from India had been relieved of all their belongings by Hindus and Sikhs, the Sikh migrants must also depart without their possessions. The Sikhs were now too helpless to resist. Their belongings were loaded onto military lorries and driven off.The column then marched for two days under difficult conditions without any further incident. The border was 3 km away when they halted for the night on September 30. The migrants, perhaps, would have heaved a sigh of relief having come within a stone’s throw of asylum. However, unbeknown to the migrants, the CO had laid a sinister snare for them which would be sprung that night. They were now without help and at a very remote location. It would be days before their fate would be known to anyone.

A little after midnight, the two leaders of the Sikh column, Bakhtawar Singh and Bhag Singh, were roused from their slumber and told that they must get ready to start walking immediately. They protested and expressed their suspicion at being suddenly ordered to march at the dead of night. By way of answer, the CO had them bayoneted and killed. The rest of the column was gathered and moved off, but after they had gone a short distance, firing was heard ahead and they were ordered to halt. They were told that the firing was coming from a gang of armed Hurs, who were waiting in ambush. This was, of course, all a hoax. The CO had sent a few of his own men ahead who, as planned, were firing in the direction of the column.

On the pretext of an imminent attack by Hurs, the young women were separated under threat of violence and distributed among the sepoys. Having secured their loot and prey, the troops were anxious to get rid of men, old women and children. They were thus told to make a run for the border. At the same time, the escort began firing their rifles indiscriminately. Some of the Sikhs ran wildly forward in the direction of the border while the rest struggled after them. The troops from behind and those in hiding kept up a steady fire.

In the darkness and confusion, scores of stragglers were killed or wounded. At the time, it was impossible to tell if any of the column had survived. A few years later, when Sir Moon came in contact with some members of the ill-fated expedition, he learnt that a good many were able to reach Chauki Kishangarh safely. Camels were then sent out from there to the scene of the firing to bring in the wounded, most of whom were ultimately transported to Jodhpur and admitted to the hospital there. Sir Moon estimated that about 6-700 of the migrants survived the ambush. Sadly, nearly 1,300 lost their lives.

The presence of kidnapped women in Rahim Yar Khan could not be concealed and a whispering campaign spread in the city. A number of these women escaped from their captors and hid themselves in the tall standing crops just outside the town. There followed a regular game of hide-and-seek. In broad daylight, soldiers of the Bahawalpur Army were seen hunting these young women from one millet field to another. Some of them were recaptured, while others got away altogether, and were given shelter in various houses in the town. The respectable inhabitants of the city were greatly enraged and reported the presence of abducted women to the police. In the course of the year, all the women except 27 were recovered and repatriated to India.

When this story of coldblooded and treacherous murder came to the notice of the state authorities, they instituted an inquiry and arrested the CO. A few days later, however, he escaped to Multan, certainly with the connivance of his military guards. He crossed the Sutlej to Multan, beyond the jurisdiction of Bahawalpur.

This story of treacherous murder of innocent people is similar to the fate that befell Muslim migrants, as described in the first part of this article. As such, these two tales represent the calamity that Punjab went through at the hands of its own people.

Both sides indulged in the genocide. Khushwant Singh noted in his novel Train to Pakistan,

“The fact is, both sides killed. Both shot and stabbed and speared and clubbed. Both tortured. Both raped.”

To be fair, the main national leaders including Mahatma Gandhi-ji, the Quaid-e-Azam and Pandit Nehru never encouraged violence and asked their followers to stay calm and peaceful. However, the central leadership had lost control over masses. The command of streets had gone in the hands of armed goons, militant politicians, renegade security officials and fanatic religious leaders. Humanity suffered.

The Partition massacres were a sad episode in the history of the Subcontinent, and one of the greatest tragedies that mankind has ever known.