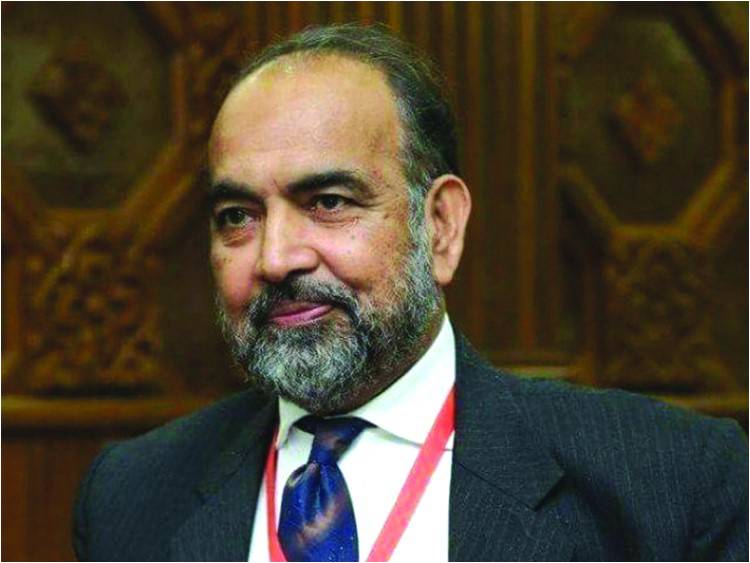

When Dr Qibla Ayaz, a progressive Muslim scholar and a former dean of faculty of Islamic and Oriental Studies, was appointed as chairman of the Council of Islamic Ideology (CII) in November 2017, there were great hopes that the Council will finally begin shedding its baggage of the past. But those hopes were dampened last Friday when the conservatives rejected a proposed legislation banning child marriage.

The Council’s opinion on child marriage borders on the ridiculous. Recognising that child marriage was not acceptable, it called for a mass awareness campaign to discourage the practice, yet rejected any legislation on this issue. “Many complications will arise due to legislation on fixing 18 years of age for marriage,” it said.

Of course the Council’s advice is not binding as law-making authority rests with the Parliament and the Parliament alone. The Council may render any opinion but the Parliament can reject it, as it has done so in the past.

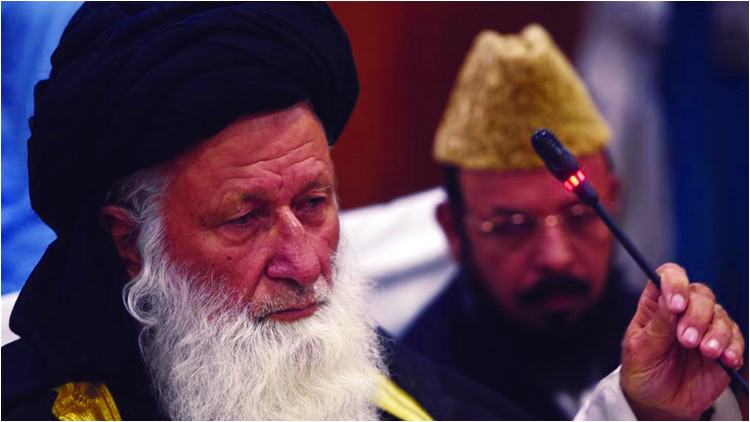

The Sindh Assembly enacted in April 2014 a law prohibiting child marriages. The then chairman of the Council, Moulana Shirani was so miffed that he accused members of the provincial legislature of “violating the Constitution” and demanded their trials for treason. His call only provoked laughter. A year later, in 2015, the government of the Punjab also enacted its child marriage act. And last week, the Senate also passed a similar law which is yet to pass through the National Assembly.

This is not the first time the Council has made controversial pronouncements.

It has opposed moves to establish homes for the elderly for being “against the society’s norms and traditions.” It rejected the Women Protection Bill of 2006, being “contrary to the spirit of Quran.” Ignoring a Supreme Court verdict that made DNA tests mandatory, it declared “unacceptable” these test results in rape cases— a declaration that made the Council look like it was actually condoning rape.

A few years ago, the Council approved the draft of a resolution recommending amending the grossly misused blasphemy law, but soon it surrendered before the hardliners and went back on its recommendation. The Council also opposed the family laws that require permission of the first wife mandatory before contracting a second marriage.

Back in the days of a military dictator, in 1978, it recommended that Kalima and Allah-o-Akbar be inscribed on the national flag to inspire people for martyrdom and jehad. Not surprisingly, the army later adopted the motto ‘iman,taqwa, jehad fi sabilillah’ (faith, piety and jehad in the cause of Allah) - a motto since abandoned. Unsurprisingly, the flag of the Taliban bears symbols then prescribed by the Council.

When the previous Council called for a ban on hate speech, it did so only on the eve of Muharram. While this in itself is welcome, the Council chose not to comment on hate speeches spewed daily against non-Muslims by religious fanatics, nor did it have any words for the hateful references used against them in textbooks.

There is need for a sustained, serious and unbiased discussion on the role of the Council.

An important point is missed by those who push the argument that it is merely an advisory body and that there is no harm if it continues. Because of an authoritarian baggage of the past, its pronouncements tend to wrongfully acquire an air of moral authority. When flaunted, this divisive and self-assumed moral authority has serious consequences for the state and society.

When set up the Council, the constitutional mandate was to review existing laws for repugnancy to Islam and to submit a “final report” to the Parliament within seven years. It not only submitted its “final report” in 1997 and a “special report” in 2008, it is continuing to submit reports to the Parliament without any legal basis or solicitation. To give it credit, the Council in its 2011 report admitted that though there was no legal basis, it was submitting reports in the interest of continuity. Who asked for continuity remains unexplained.

General Zia, through a controversial executive fiat, introduced in the Constitution a Federal Shariat Court with powers to strike down any law it deemed un-Islamic. Is the Council, then, really needed which neither has powers to strike down a law nor has legal justification to continue after submitting “final reports”? What is there to be gained from this advisory body whose pronouncements have neither served the cause of Islam, nor democracy nor progress?

For seeking experts’ opinions on legislation, the Parliament’s rules provide for holding public hearings to which religious scholars may also be invited if needed. If, as Allama Iqbal said, the ulema wanted legislation in accordance with their worldview, they should first get themselves elected to the legislature instead of dictating it from outside.

It appears that a small group of un-elected clergy, which first entered the constitutional edifice as mere advisors for a limited period, have ensconced themselves permanently to play a role beyond their constitutional mandate. A serious thought needs to be given to the role and responsibilities of the Council no matter how well-intentioned, pious or scholarly some individual members may be.

The writer is a former senator.

The Council’s opinion on child marriage borders on the ridiculous. Recognising that child marriage was not acceptable, it called for a mass awareness campaign to discourage the practice, yet rejected any legislation on this issue. “Many complications will arise due to legislation on fixing 18 years of age for marriage,” it said.

Of course the Council’s advice is not binding as law-making authority rests with the Parliament and the Parliament alone. The Council may render any opinion but the Parliament can reject it, as it has done so in the past.

The Sindh Assembly enacted in April 2014 a law prohibiting child marriages. The then chairman of the Council, Moulana Shirani was so miffed that he accused members of the provincial legislature of “violating the Constitution” and demanded their trials for treason. His call only provoked laughter. A year later, in 2015, the government of the Punjab also enacted its child marriage act. And last week, the Senate also passed a similar law which is yet to pass through the National Assembly.

This is not the first time the Council has made controversial pronouncements.

It has opposed moves to establish homes for the elderly for being “against the society’s norms and traditions.” It rejected the Women Protection Bill of 2006, being “contrary to the spirit of Quran.” Ignoring a Supreme Court verdict that made DNA tests mandatory, it declared “unacceptable” these test results in rape cases— a declaration that made the Council look like it was actually condoning rape.

A few years ago, the Council approved the draft of a resolution recommending amending the grossly misused blasphemy law, but soon it surrendered before the hardliners and went back on its recommendation. The Council also opposed the family laws that require permission of the first wife mandatory before contracting a second marriage.

Back in the days of a military dictator, in 1978, it recommended that Kalima and Allah-o-Akbar be inscribed on the national flag to inspire people for martyrdom and jehad. Not surprisingly, the army later adopted the motto ‘iman,taqwa, jehad fi sabilillah’ (faith, piety and jehad in the cause of Allah) - a motto since abandoned. Unsurprisingly, the flag of the Taliban bears symbols then prescribed by the Council.

When the previous Council called for a ban on hate speech, it did so only on the eve of Muharram. While this in itself is welcome, the Council chose not to comment on hate speeches spewed daily against non-Muslims by religious fanatics, nor did it have any words for the hateful references used against them in textbooks.

There is need for a sustained, serious and unbiased discussion on the role of the Council.

An important point is missed by those who push the argument that it is merely an advisory body and that there is no harm if it continues. Because of an authoritarian baggage of the past, its pronouncements tend to wrongfully acquire an air of moral authority. When flaunted, this divisive and self-assumed moral authority has serious consequences for the state and society.

When set up the Council, the constitutional mandate was to review existing laws for repugnancy to Islam and to submit a “final report” to the Parliament within seven years. It not only submitted its “final report” in 1997 and a “special report” in 2008, it is continuing to submit reports to the Parliament without any legal basis or solicitation. To give it credit, the Council in its 2011 report admitted that though there was no legal basis, it was submitting reports in the interest of continuity. Who asked for continuity remains unexplained.

General Zia, through a controversial executive fiat, introduced in the Constitution a Federal Shariat Court with powers to strike down any law it deemed un-Islamic. Is the Council, then, really needed which neither has powers to strike down a law nor has legal justification to continue after submitting “final reports”? What is there to be gained from this advisory body whose pronouncements have neither served the cause of Islam, nor democracy nor progress?

For seeking experts’ opinions on legislation, the Parliament’s rules provide for holding public hearings to which religious scholars may also be invited if needed. If, as Allama Iqbal said, the ulema wanted legislation in accordance with their worldview, they should first get themselves elected to the legislature instead of dictating it from outside.

It appears that a small group of un-elected clergy, which first entered the constitutional edifice as mere advisors for a limited period, have ensconced themselves permanently to play a role beyond their constitutional mandate. A serious thought needs to be given to the role and responsibilities of the Council no matter how well-intentioned, pious or scholarly some individual members may be.

The writer is a former senator.