After two years, Pakistan has been elected to the prestigious UN Human Rights Council but the decision to include it has prompted a backlash, as it highlights the country’s failings in protecting the human rights of its own citizens.

To secure membership to the UNHRC, Pakistan had to pledge its commitment to uphold the highest standards in the promotion and protection of universal human rights and fundamental freedoms for all. The country’s election to the intergovernmental rights body was celebrated by Maleeha Lodhi, permanent representative to the UN, as being “an endorsement of Pakistan’s strong commitment to human rights”.

Many human rights activists disagree with Lodhi’s sentiments and the move was generally regarded as unpopular.

The main issue activists have taken is that various national and international human rights organisations, UN treaty-monitoring bodies and special procedures of the UNHRC have repeatedly condemned Pakistan’s abuse of human rights. The US government was, for instance, critical of the country’s election, with Nikki Haley, US ambassador to the UN, claiming that the judgment proves that the Council lacks credibility and is in need of reform.

Attaullah Mengal, former chief minister of Balochistan, was also critical, stating that, “Pakistan’s election to the UN Human Rights Council is an insult to those who are victims of Pakistan’s oppression… it means the international community is turning a blind eye to rights violations (in the country).”

According to the Universal Periodic Review of Pakistan, human rights concerns in Pakistan include: an increase in intimidation and attacks on the media by state and independent actors; restrictions on NGOs, illegal detainment of suspects and torture in custody, particularly against those involved in cases of terrorism; discrimination against religious minorities; and a failure to protect the rights of vulnerable social groups, such as women, children, the poor, the disabled and the LGBT community.

Pakistan’s next universal periodic review is set to take place on November 13, 2017, at the Human Rights Council, in Geneva. However, most recommendations made in the 2012 review, five years ago, have still not been implemented and enforced. The one notable positive development was the passing of the National Commission on the Rights of the Child Act of 2017, however it was never given adequate financial support and established as an independent body to enforce child rights. Children remain vulnerable to attacks on schools, use by Taliban and affiliated armed extremist groups in suicide bombings, a lack of education, malnutrition, sexual abuse, exploitation and alleged torture and ill treatment in policy custody.

One important issue that affects children, and girls in particular, is child marriage. The Child Rights Movement has recommended amending the Child Marriage Restraint Act of 1929 to increase the minimum marriageable age for girls from 16 to 18 years. Surprisingly, the Senate’s Standing Committee on Interior initially rejected the Bill, declaring it un-Islamic. The Bill was later cleared after criticism emerged from civil society, but it has yet to be passed by parliament, as it remains stuck in red tape.

The Global Gender Gap Index ranked Pakistan as the second-worst country in the world to be a woman, with high numbers of child marriages, rapes, acid attacks, forced marriages, and domestic violence. Pakistani activists estimate that there are 1,000 “honour killings” every year, with a recent headline-generating example being that of Qandeel Baloch in July 2016.

Women from religious minority communities are exceptionally vulnerable. A report found that at least 1,000 Christian and Hindu women were forced to marry Muslim men every year. Certain laws are generally incompatible with the rights to freedom of expression, freedom of religion and equal treatment before the law, as they are used to target minorities. Even within Muslims, violence between sects (e.g. increased attacks on Shia shrines and the recent murder of a Christian schoolboy) lead to the persecution of marginalised people. Three men from a minority community were sentenced to death on charges of blasphemy. Dozens are facing blasphemy charges, with at least 17 people on death row.

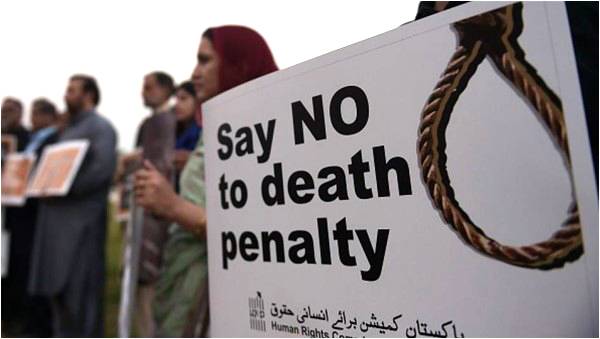

The death penalty still exists in Pakistan, making it 1 of 58 countries that still practice capital punishment, after a moratorium on the penalty was lifted, in 2014. Most death row inmates have been convicted of ordinary criminal offences and the majority of death row inmates are from poor backgrounds. There is a strong, purely emotional, sentiment in favour of keeping the death penalty, however rights activists argue that it is morally unjust to take life, especially in cases where the convict is either innocent or guilty of a disproportionately small crime. A better, more humane proposed alternative may be life imprisonment and rehabilitation schemes.

Here, there is an important shift in focus from human rights violations as incidences at an individual or community level to an institutional problem, where the criminal justice system itself can be manipulated.

A stand-out example of this can be seen in the operation of military courts that were formed to handle terrorism cases, in the 21st constitutional amendment, as opposed to reforming the flawed judiciary, law-enforcement and penitentiary systems. Since January 2015, the courts have convicted at least 305 people, with 169 being sentenced to death. There are no safeguards to ensure that court proceedings uphold the international standards of a fair trial, which puts a question mark on any judgement passed by them.

The issue of human rights is illustrated in the saying, ‘the personal is political’, as normalised abuse of the oppressed common man is connected to the larger social and political structures in place. Having barely scratched the surface of the scope of human rights violations in Pakistan, it is apparent that it is a problem that requires reflection and accelerated efforts from the authorities concerned. The common justification provided for the inclusion of Pakistan in the UNHCR is that it adds moral pressure for them to do just this, with an example being that of Saudi Arabia, another controversially included member of the international rights body, recently granting women the right to drive.

However, I argue that such measures will be ineffective without the support of a strong civil government to follow-up, as shown by the number of UPR recommendations that remain unimplemented to date. Hence, the forecast for human rights, in the present political landscape, is pessimistic.

To secure membership to the UNHRC, Pakistan had to pledge its commitment to uphold the highest standards in the promotion and protection of universal human rights and fundamental freedoms for all. The country’s election to the intergovernmental rights body was celebrated by Maleeha Lodhi, permanent representative to the UN, as being “an endorsement of Pakistan’s strong commitment to human rights”.

Many human rights activists disagree with Lodhi’s sentiments and the move was generally regarded as unpopular.

The main issue activists have taken is that various national and international human rights organisations, UN treaty-monitoring bodies and special procedures of the UNHRC have repeatedly condemned Pakistan’s abuse of human rights. The US government was, for instance, critical of the country’s election, with Nikki Haley, US ambassador to the UN, claiming that the judgment proves that the Council lacks credibility and is in need of reform.

Attaullah Mengal, former chief minister of Balochistan, was also critical, stating that, “Pakistan’s election to the UN Human Rights Council is an insult to those who are victims of Pakistan’s oppression… it means the international community is turning a blind eye to rights violations (in the country).”

We barely scratch the surface on the scope of human rights violations in Pakistan. Including Pakistan in the UNHCR is justified as adding moral pressure to act. Saudi Arabia is cited as another controversially included member that recently granted women the right to drive

According to the Universal Periodic Review of Pakistan, human rights concerns in Pakistan include: an increase in intimidation and attacks on the media by state and independent actors; restrictions on NGOs, illegal detainment of suspects and torture in custody, particularly against those involved in cases of terrorism; discrimination against religious minorities; and a failure to protect the rights of vulnerable social groups, such as women, children, the poor, the disabled and the LGBT community.

Pakistan’s next universal periodic review is set to take place on November 13, 2017, at the Human Rights Council, in Geneva. However, most recommendations made in the 2012 review, five years ago, have still not been implemented and enforced. The one notable positive development was the passing of the National Commission on the Rights of the Child Act of 2017, however it was never given adequate financial support and established as an independent body to enforce child rights. Children remain vulnerable to attacks on schools, use by Taliban and affiliated armed extremist groups in suicide bombings, a lack of education, malnutrition, sexual abuse, exploitation and alleged torture and ill treatment in policy custody.

One important issue that affects children, and girls in particular, is child marriage. The Child Rights Movement has recommended amending the Child Marriage Restraint Act of 1929 to increase the minimum marriageable age for girls from 16 to 18 years. Surprisingly, the Senate’s Standing Committee on Interior initially rejected the Bill, declaring it un-Islamic. The Bill was later cleared after criticism emerged from civil society, but it has yet to be passed by parliament, as it remains stuck in red tape.

The Global Gender Gap Index ranked Pakistan as the second-worst country in the world to be a woman, with high numbers of child marriages, rapes, acid attacks, forced marriages, and domestic violence. Pakistani activists estimate that there are 1,000 “honour killings” every year, with a recent headline-generating example being that of Qandeel Baloch in July 2016.

Women from religious minority communities are exceptionally vulnerable. A report found that at least 1,000 Christian and Hindu women were forced to marry Muslim men every year. Certain laws are generally incompatible with the rights to freedom of expression, freedom of religion and equal treatment before the law, as they are used to target minorities. Even within Muslims, violence between sects (e.g. increased attacks on Shia shrines and the recent murder of a Christian schoolboy) lead to the persecution of marginalised people. Three men from a minority community were sentenced to death on charges of blasphemy. Dozens are facing blasphemy charges, with at least 17 people on death row.

The death penalty still exists in Pakistan, making it 1 of 58 countries that still practice capital punishment, after a moratorium on the penalty was lifted, in 2014. Most death row inmates have been convicted of ordinary criminal offences and the majority of death row inmates are from poor backgrounds. There is a strong, purely emotional, sentiment in favour of keeping the death penalty, however rights activists argue that it is morally unjust to take life, especially in cases where the convict is either innocent or guilty of a disproportionately small crime. A better, more humane proposed alternative may be life imprisonment and rehabilitation schemes.

Here, there is an important shift in focus from human rights violations as incidences at an individual or community level to an institutional problem, where the criminal justice system itself can be manipulated.

A stand-out example of this can be seen in the operation of military courts that were formed to handle terrorism cases, in the 21st constitutional amendment, as opposed to reforming the flawed judiciary, law-enforcement and penitentiary systems. Since January 2015, the courts have convicted at least 305 people, with 169 being sentenced to death. There are no safeguards to ensure that court proceedings uphold the international standards of a fair trial, which puts a question mark on any judgement passed by them.

The issue of human rights is illustrated in the saying, ‘the personal is political’, as normalised abuse of the oppressed common man is connected to the larger social and political structures in place. Having barely scratched the surface of the scope of human rights violations in Pakistan, it is apparent that it is a problem that requires reflection and accelerated efforts from the authorities concerned. The common justification provided for the inclusion of Pakistan in the UNHCR is that it adds moral pressure for them to do just this, with an example being that of Saudi Arabia, another controversially included member of the international rights body, recently granting women the right to drive.

However, I argue that such measures will be ineffective without the support of a strong civil government to follow-up, as shown by the number of UPR recommendations that remain unimplemented to date. Hence, the forecast for human rights, in the present political landscape, is pessimistic.