There is a strange visual duality to time. Draw it out on a piece of paper, and you often end up with a line interrupted by three distinct intervals. The farthest to the left, the past, the farthest to the right, the future, and one tucked right in the middle, the present. But step outside this linear view to observe time like a slow-moving cycle of nature, and time seems embedded in everything around us – bending, spiralling, growing.

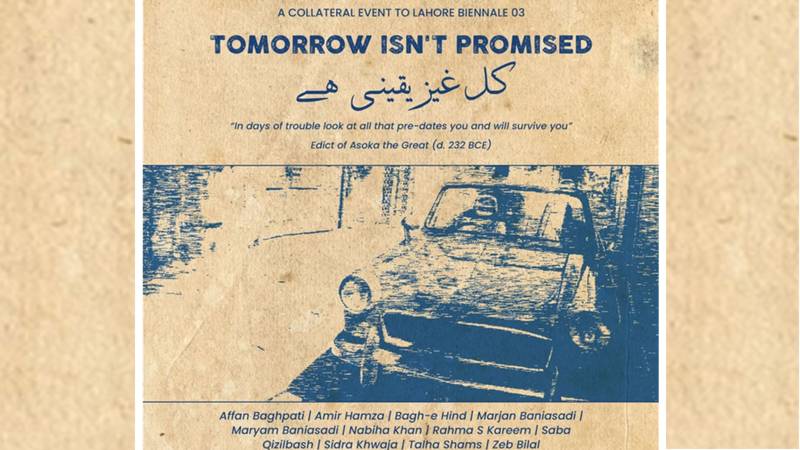

11 Temple Road, Mozang, stands as witness to this cyclical, layered state of time, and the show Tomorrow Isn’t Promised – a collateral show to the Lahore Biennale Festival (03), 2024 – adopts the same function of the century old house itself. The show creates a dialogue around embodying both permanence and the fleeting quality of human impact on Nature.

Tomorrow Isn’t Promised, curated by Fatma Shah, begins by contrasting Nature's timelessness with the transience of human impact. In the garden, the Listening Tree by Nabiha Khan and Zeb Bilal is a life-sized tin structure. This embodies both the nurturing spread of Nature and her peacock-like flamboyance through its strung, silver arms. The embrace it visually represents pays dark homage to the constant transmutation human activity has been forcing on Nature. Yet, in front of Real Nature, the gigantesque Banyan which is a part of 11 – Temple Road, this representation is scaled down to a mere grain of sand against the rolling desert of time. This apparent bitter sweetness between Nature and humans seems to say that “tomorrow” isn’t as hopeless—after all, what is a few years of human damage to a tree more than hundred years old?

Unless that damage takes shape of the violence inherent to human behaviour.

Inside the house, this is depicted in the very painful gallery walk through everything that is ravaged by human carnage. Nothing is left behind in time except the means of destruction in the miniatures of Ameer Hamza. In The Abyss (2023) and Hollow Phrase (2023), there is a jarring absence of human existence amongst their weapons of invasion and destruction. Only these are left behind poised in eternal action as human’s only mark on Nature. Angels take form of evolutionary concoctions a result of forced adaptation in the objects of Affan Baghpati. Teasing (Farishta series) (2024) and Falling (Farishta series) (2024) both show mutated forms of heavenly beauty in animals that is forced into bizarre metallic growth through human industry. Human traditions and their softer relationships with Nature struggle against obscurity in the crafts of Sidra Khawaja. A Map Shawl of Kashmir (2022) is proof of a kinder relationship between humans and Nature. The motif handiwork of native craftsmen, their intrinsic knowledge of intricate colours and patterns mimics Nature as it is and mirrors more ominous forms of human violence that wipes her clean.

11 Temple Road, Mozang, stands as witness to this cyclical, layered state of time, and the show Tomorrow Isn’t Promised – a collateral show to the Lahore Biennale Festival (03), 2024 – adopts the same function of the century old house itself

Finally, humans swallow their own existence in narrative time-maps by Saba Qizilbash. Her work From Skardu to Kargil (2021) displays the intersection of Nature’s beauty and human territorialism in the form of a detailed drawing that shows the continuous past being changed at the Line of Control (LOC) in the region. Tomorrow Isn’t Promised then appears to claim that not everything is what it seems, and a new day cannot be guaranteed anymore since the landscape of Nature has been plagued for too long by humans.

As the show progresses, it explores ways to protect what remains, clinging to hope. Marjan Baniasadi’s paintings depict intricate tapestries of animals from a premature past and imagined present. And urbanisation is displayed for all to see in the living, breathing, dying spaces of Rahma Shahid Karim. Change as a Constant (2024), a part of the River City set up in the immersive exhibition space, conserves the Ravi River however it can through the ravages of time. The effect of time passing and ecocide is taken and turned pocket-sized like viewing the past, present, and future of Nature as though in an hourglass. Indigenous plants wilt, natural resources are utilised, and the living land is cleared to make space for human life. Here, Tomorrow Isn’t Promised appears to claim that grain upon grain of human liability overtime results in catastrophic loss of Nature that is irreversible.

Unless humans forefront the fight for environmental protection themselves.

The last piece of this show portrays this point through the screening of Life in the Walled City of Lahore (1991) by Shireen Pasha. Where exists the violence inherent to human beings, there also exists human resilience against it. The 45-minute film depicts the seamless integration of human activity in Nature and time. Humans make lives around everything Nature provides, forming sustenance from what she grows, moulding objects from what she forms, and experiencing life against the backdrop of her skies. Co-existence, co-nurturing, co-preservation are possible, Fatma Shah seems to say. What is for sure is that Tomorrow Isn’t promised, it is not a given like everything humans have taken for granted in Nature. But tomorrow can be promised because both the Banyan and humans who stay to fight for it have managed to remain in the face of human destruction of the self and otherwise.