Translating Urdu ghazal, defined by its non-negotiable metre, rhyme, alliterative infrastructure, is, according to literary critic Nasir Abbas Nayyar, challenging primarily for two reasons: “one, the language employed in (Urdu) poetry is so culturally distinct that its exact linguistic parallel cannot be found in any other language; two, ideas and thoughts of poetry are heavily soaked in emotions and feelings, expressed through a unique yet elusive cognitive process involving distinctive, metaphoric language.” Neither can be replicated exactly “by even the most skilled translator,” states Nayyar.

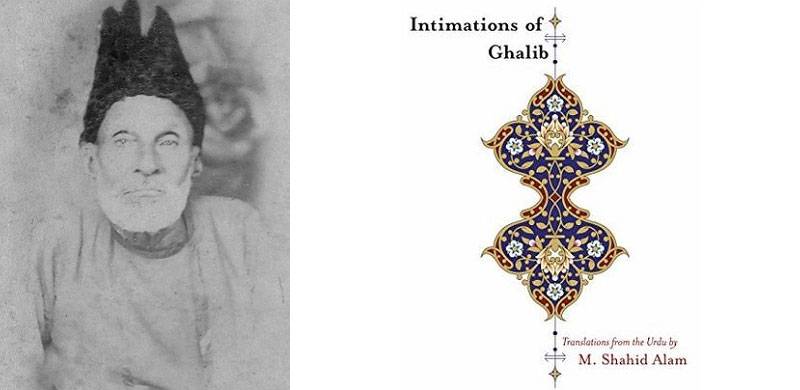

And yet, despite this vast array of reasons, Urdu poetry, particularly that of Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib has always been translated the world over. Frances Pritchett is perhaps the most well-known in this arena, having translated the complete ‘Dīwān’ of Ghalib into English, while struggling to maintain the essence that is Ghalib. Pritchett invested almost a lifetime in this pursuit. In part it is also related to the complexity of Ghalib’s thought. “Translating Ghalib,” she stated, “is a no-win situation… in all of world literature, there can be few genres less translator-friendly than the classical Urdu ghazal, and in all classical ghazal, there can hardly be a poet more resistant and opaque to translation than Ghalib.”

British scholar-translator of Urdu literature Ralph Russel also noted that a translator of Ghalib should regard his (Ghalib’s) concern for “appropriate diction, rhyme, rhythm, assonance, alliteration and all kinds of verbal conceits is as evident as it is in his verse.”

According to Russel, apart from the problem of completely mapping meaning onto another language, other factors are also impediments. The first of these is rhyme. The ghazal constitutes a number of couplets, usually following a uniform metre, and a rhyme scheme which follows: AA, BA, CA, DA, and so on. To map this rhyme scheme onto English and achieve the same effect as that in Urdu is a task almost impossible to achieve, he adds. “You are faced with the stubborn and unalterable fact that Urdu has rhyming words in plenty, and English has not.” In that case, as in most ghazal cases, one is compelled to “translate a poem knit together by a unity of rhyme into one where this kind of unity cannot be maintained.”

The second is the issue of metre, for it varies greatly for Urdu and English. “In English, the essential determinant of metrical pattern is the inherent stress pattern in each English word; In Urdu, metre is essentially based upon quantity considerably modified, however, by the incidence of a sort of stress comparable to the beat in music.” In many cases, Russel adds, the rhythm of Ghalib’s verses is not adaptable to any other English pattern. And so, the best possible option is to achieve the same number of syllables with some discernible rhythm. Often, translators attempt to match Urdu phrases of Ghalib with what they know as proper English idioms, but sometimes they are unable to do so.

Given such hurdles, Alam’s work is commendable. As he notes in his introduction, “I have tried to retain the imagery, metaphors, cadences, conventions, the Ghazals, dramatis personae, the two-line format of the she’r and the compact appearance of the Ghazal on the page.” While such intimacy with the text is apparent from the translations in this volume, the real feat of Alam is to acknowledge the multiplicity of meaning in Ghalib’s verse. At the same time, he confesses that there may be limits to his understanding and grasp of the verse. This is why the translator, in some cases, offers two versions of the same original. For instance, taking one enigmatic verse of Ghalib, Alam offers five versions – and each of these versions uncovers the layer of meaning.

نقش فریادی ہے کس کی شوخیٔ تحریر کا

کاغذی ہے پیرہن ہر پیکر تصویر کا

Shaped for eternity; Yet tied to times cross

What did he think whose hands crafted us

Another celebrated verse is interpreted twice.

نہ گل نغمہ ہوں نہ پردۂ ساز

میں ہوں اپنی شکست کی آواز

No roseate song, no silk spun melody.

I am the last echo of my old defeat.

The second version is as follows:

Not Canticle nor music weaving

Listen to my heart grieving

Consider this translation which captures the expanse of meaning in Ghalib’s poetic imagination.

گلہ ہے شوق کو دل میں بھی تنگئ جا کا

گہر میں محو ہوا اضطراب دریا کا

Inside the heart, love carves, it lacks space.

Inside a pearl, the raging sea is free

The 35 ghazals selected by Alam provide a useful introduction to the great Master, especially for the uninitiated readers. The selection by Alam is by no means exhaustive, nor does it capture the full range of Ghalib’s imagination, but it presents an enjoyable miniature feast. More importantly, Ghalib’s existentialist angst, tumultuous personal life and the upheavals he encountered are reflected in the ghazals selected by Alam. For instance, after losing all his children, Ghalib and his wife adopted their nephew who also died. He composed this soul stirring ghazal “Lazim tha ke dekho mera rasta koi din aur..”

لازم تھا کہ دیکھو مرا رستا کوئی دن اور

تنہا گئے کیوں اب رہو تنہا کوئی دن اور

God, you have eternity; yet he

Could not have an extra day

Another couplet that is often cited as an indication of Ghalib’s profound insight into human nature has been effortlessly translated by Alam:

A drop craves extinction in the sea

Past plentitude, pain becomes remedy.

عشرت قطرہ ہے دریا میں فنا ہو جانا

درد کا حد سے گزرنا ہے دوا ہو جانا

I would add that the choice of verses itself is a testament to the fact that the translator is a jeweler who can identify the best gems from a sack of precious stones.

The scholars, students and those who care for poetic traditions outside the Euro-Atlantic hegemon will certainly benefit from this work that at the very least exhibits devotion to an unsung master of world poetry. Guy Rotella, Emeritus Professor of English Literature, Northeastern University, in his foreword sums it up well: “Translation loses things, and readers from outside a writer’s culture lose a great deal more. But translators help us recover some of what we’ve lost or otherwise could never have at all.”