“No plan of operations extends with certainty beyond the first encounter with the enemy's main strength”

(Field Marshal von Moltke)

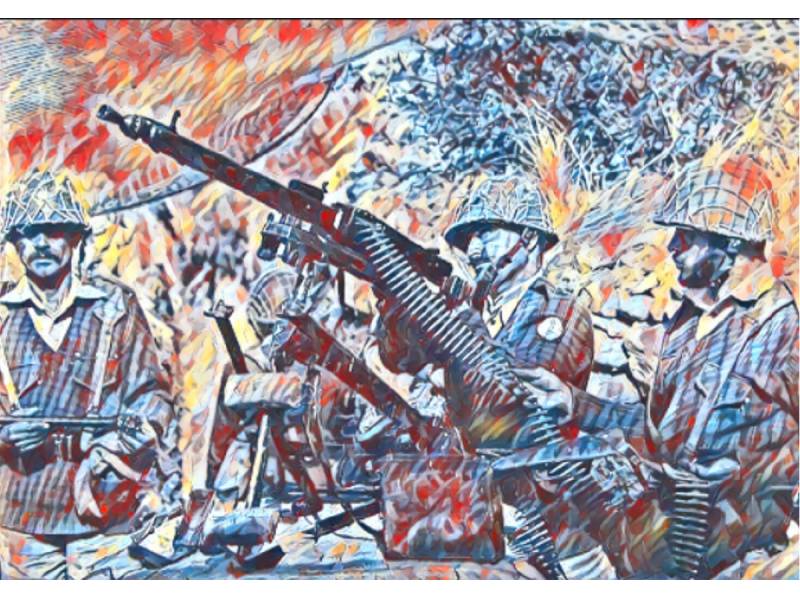

There is no question that Pakistan’s army did a remarkable job of saving Lahore, the cultural capital of the nation and its second-largest city, on September 6 when it was attacked by three divisions of the Indian army. Soldiers and officers of the Pakistan army fought off the invaders with exemplary valour and skill. Rightfully, Pakistan honours the fallen every year on Defence of Pakistan Day.

Why did India attack Lahore in the first place? President Field Marshal Ayub Khan went on Radio Pakistan and said India attacked because it had never accepted the idea of Pakistan. That was a politically expedient answer, but it was not the truthful answer.

Ayub had authorised the injection of guerilla fighters into Kashmir to liberate it from Indian occupation on August 5. His foreign minister, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, had convinced him that the time to strike had come. After its border war with China in 1962, India was being armed heavily by the western powers. In a few years, Bhutto argued, it would become too strong for Pakistan to take on.

The Pakistani army had a trial run against its Indian counterpart in the Rann of Kutch in April 1965. The Indian army had not performed well and Ayub had concluded, prematurely as events would later reveal, that “the Hindu has no stomach for a fight.” His hubris had risen to such a level that he would often be heard saying that “one Pakistani soldier is worth ten Indian soldiers.”

Bhutto had convinced him that the incursion of guerilla fighters into Kashmir would stir a revolt among its largely Muslim population, who wanted to be rescued from the clutches of their Hindu masters, forcing India to withdraw its troops from the region.

General Musa, the commander-in-chief, was concerned that Pakistan’s operations in Kashmir might trigger an all-out war with India. But Bhutto overruled him and convinced Ayub to proceed with the operation in Kashmir.

Pakistan had multiple defence treaties with the US and its army and air force were equipped with American arms. It expected the US would come to its aid in any war that broke out with India, overlooking the fact that those treaties were exclusively directed at containing communism. In addition, Pakistan had created a new relationship with China, and both countries called each other “all-weather friends.”

As 1965 began, the armed forces of Pakistan exuded a sense of self-confidence and pride that had not been seen in years.

The guerilla intervention had been planned for months. It was code name Operation Gibraltar. That exalted name was designed to boost morale by drawing a parallel with Tariq bin Ziad’s successful invasion of Spain in the year 711 AD at a place that would later be called Jabal al-Tariq, which would eventually become Gibraltar.

From the day it was created, Pakistan had argued that Kashmir, with its large Muslim population, belonged to Pakistan. Just two months after its creation, Pakistan sent in a few thousand “raiders” into Kashmir under the command of a serving army officer. Unfortunately for Pakistan, the raiders began to loot and plunder when they got to Baramulla, some 35 miles from Srinagar. They never made it to the capital.

That gave enough time to the Hindu Maharaja of Kashmir to sign the instrument of accession with India and plead for help in the fight against the raiders. Prime Minister Nehru responded quickly. The fighting dragged on until the end of December 1948.

Operation Gibraltar was essentially Part II of the campaign that was launched in October 1947. The Pakistani guerillas did not know the terrain or the local culture. They stuck out like a sore thumb. The locals turned them into the Indian police. Four appeared on All India Radio and confessed why they were sent. A Pakistani army officer who was listening to the broadcast said, “The blighters have spilled the beans.”

To continue the assault, Operation Grand Slam was launched with the aim of capturing Akhnoor and cutting off the road from Amritsar to Srinagar. The Pakistani forces crossed the Munawar Tawi River, captured the hamlet of Chamb, but then a mysterious and still unexplained change in command occurred. The division commander was replaced by Maj.-Gen Yahya Khan, one of Ayub’s confidants, and a man who was better known for womanizing and drinking than for his generalship. The invasion was halted, and the Indian supply lines were not cut.

As its casualties mounted in Kashmir, India launched Operation Riddle, a three-pronged attack across a 50-mile front toward Lahore at 3:30 am on September 6. Within 24 hours, the sappers of the Pakistan army had blown up all the bridges on the BRB irrigation canal that lies between Lahore and the border with India.

The Pakistani infantry put up a fierce resistance, aided by heavy and accurate fire from the artillery. Then they launched a counterattack, catching the Indians by surprise. They began to worry about the defence of Amritsar. The tide had begun to turn but Pakistan did not have enough troops to mount such an offensive.

Operation Riddle was halted within 48 hours. India shifted its attention to Sialkot and launched Operation Nepal. It was intended to cut off the G.T. road between Lahore and Rawalpindi, according to some accounts, and simply to relieve pressure on Indian forces in Kashmir.

Unlike the attack on Lahore, which was mounted by three infantry and mountain divisions, this attack was mounted by India’s 1st Armoured Division, supported by three infantry and mountain divisions. Pakistan’s 6th Armoured Division, equipped with US M47/48 Patton tanks, and ably assisted with infantry units, blunted the Indian attack. The 25th Cavalry of the Pakistani army showed that the Patton tanks were very effective in combat against the Centurion tanks of the Indian army.

Further south, Pakistan decided to seize the initiative from India by launching Operation Mailed Fist. This was led by Pakistan’s 1st Armoured Division. The objective was to cut off the GT road between Amritsar and New Delhi. The operation had commenced on an auspicious note. The division had left from its base in Multan quietly, unnoticed by India.

Its Patton tanks lay concealed in the Changa Manga forest when a Pakistani ack-ack crew prematurely fired on the IAF’s Canberra reconnaissance plane. More troubles followed.

While moving toward the border, a Patton tank fell off a bridge that was not designed to take its weight. All the Patton tanks behind it ground to a halt and became cannon fodder for the IAF. Eventually the bridge was repaired and the advance continued.

The 1st Armoured captured the village of Khem Karan, and General Musa arrived in triumph. He was photographed standing at the train station, next to a sign with the town’s name on it. Then the tanks marched into India but got bogged down in a sugar cane field.

That’s when the Indian artillery and small arms fire took down the infantry units that had come with the Patton tanks. The tanks charged ahead, despite the poor visibility, and they were taken out, one by one, by Indian troops riding in Jeeps equipped with recoilless rifles. By nightfall, 96 Pakistani tanks had been destroyed. The invasion died an early death.

The failure of this counter-attack doomed Pakistan’s Kashmir initiative. Had the Pakistani counter-offensive succeeded, it would have destroyed Indian forces between the Beas River and the international border. As an Indian general wrote, “East of that point, up to Delhi, the Grand Trunk Road lay open, practically undefended, with all our forces on the other side of the Beas—thus bringing within an ace of realisation Ayub’s dream of ‘strolling up’ to Delhi.”

Why, then, did Pakistan stop combat operations with India in September 1965 just two-weeks into a full-scale war? First, soon after India invaded Lahore, China issued an ultimatum to India to withdraw. That lifted spirits in Islamabad, but New Delhi simply ignored the ultimatum. Second, the army had begun to run out of artillery shells and the air force was running out of starter cartridges for the F-86 Sabre jets. When President Ayub was informed of these developments, he turned pale. The US had already imposed an arms embargo on both India and Pakistan. It affected Pakistan a lot more than India because most of Pakistan’s weaponry was US made. The curtain had fallen. Ayub knew the game was over.

A few months after the ceasefire, in January 1966, a humbled and sober Ayub signed a peace deal with India’s Prime Minister Shastri in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, under Soviet auspices, promising to give up whatever pieces of Indian territory Pakistan had acquired. The status of Kashmir remained unchanged, despite the loss of life and treasure.

In Pakistan, the letdown in expectations was huge. To divert the public’s attention, Ayub arrested a leading East Pakistani politician, Mujibur Rahman, on charges of treason. He put him on trial in the Agartala Conspiracy case.

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who had pushed Ayub to initiate hostilities in Kashmir by saying that in a few years India would be too powerful for Pakistan to fight, turned on Ayub, who fired him as foreign minister. Bhutto went on to create his own political party in 1967, becoming yet another thorn in the dictator’s side.

An economic slowdown caused by the war set in. Ayub sought to deflect attention by observing a poorly timed “Decade of Development” in 1968. Riots broke out everywhere in the country. Rallies were held in every major city denouncing him as a “dog.” Ayub held a Round Table Conference with all the opposition parties, hoping to calm them down. It was the proverbial case of “too little, too late.”

In March 1969, a depressed Ayub confided to his hand-picked army chief, Gen Yahya, the man who had failed to conquer Akhnoor in Kashmir, that the people had gotten tired of seeing his face. He asked Gen Yahya to declare martial law. Yahya agreed on one condition: that Ayub hand over the presidency to him. Ayub had no other option. He was overthrown by the army in a sorry reminder of what he had done in October 1958, when he had removed President Iskander Mirza from office and sent him into exile to London. If there was a saving grace, it was that Ayub was allowed to remain in Pakistan.

East Pakistan had sensed its isolation in the 1965 war. A single army division, the 14th Infantry Division, was stationed there and a single PAF squadron. Its Bengali population had long standing grievances against their economic neglect by the Pakistani government which was not only based in Islamabad but also dominated by West Pakistanis and which had sought to impose Urdu, a language only spoken in the West, as the national language even during Jinnah’s tenure as Governor General.

When Yahya annulled the results of the 1970 general elections in which Mujib’s party had secured an absolute majority, and launched Operation Searchlight on March 25, 1971 to pin down the rebels, a civil war broke out. It was followed by a full-fledged war with India in December which Pakistan lost and in which East Pakistan seceded and became the new nation of Bangladesh.

A war to acquire Kashmir in 1965 ended up costing the country its eastern wing just 6 years later. That was a really heavy price to pay. Sadly, Pakistan did not learn its lessons and attempted once again to trigger a revolt in Kashmir in the spring of 1999 by attacking Kargil.