We were driving on the edge of a barren mountain. It was a narrow road and the traffic was thin. A few mud houses covered with thatched roofs were interspersed on the road. Young mountain children wearing long skirts were playing along the way, oblivious to the hazards of the oncoming traffic. Occasionally we would cross a group of gypsies traveling West in search of a cooler summer with the winter season headed to its conclusion.

Most of these were Balochi gypsies, carrying everything they owned on their beautiful tall camels. The men and the women walked along the road while the children sat on the top of the camels, their blue-green eyes piercing us with disdain for our sedentary lives. As a child I recall my eyes judging them for their perpetual movement. Carrying the bias of the entire settled civilization on my shoulders I used to feel a disdain for these nomadic communities whose entire worldview was different from mine. Being able to look beyond my prejudice today I could admire the elaborate dresses of the women with their colorful borders, and the ethnic caps of the men studded with glasswork.

I was accompanied by my photographer friend Rida Arif, my wife Anam and my mentor Iqbal Qaiser. “I want to become a gypsy,” suggested Rida. It was an idea that resonated with me. The concept of spending one’s entire life on the move has a charm. I imagine a life unburdened by the compulsion of making a living. No alarm clocks, no 9-5.

[quote]The international border, a sacred line in the modern iconography of nationalism doesn't exist for them[/quote]

On our right was the River Indus, the lifeline of the Indus civilization. It was snaking through the plains of the Punjab. “When Indus is a river in Pakistan than why does India derive its name from the Indus?” said Iqbal Qaiser. I smiled politely acknowledging that I had registered what he had said without adding anything more. I wasn’t exactly in the mood for having a conversation. I was enjoying the drive. But what he said was similar to what I was thinking.

Having spent the night at my uncle’s house in the city of Koniya the four of us had left after breakfast to see the ruins of ancient temples not far from the city. Koniya is a small city in the district of Mianwali, which was earlier part of the Bannu district. In 1901, when the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa was carved out of Punjab, Mianwali was made part of Punjab and given the status of an independent district.

Police at a security post stopped us to enquire about our whereabouts just before we reached the bridge on the top of Chashma Barrage with the reservoir of water on one side and the river on the other. The administrative authorities change hands at this point, hence the vigilance. We were now heading into the province of KPK and as we exited from the bridge I noticed an equally eager security check post, this time composed of KPK police officials in blue sweaters.

There was nothing in the geography of the land or the attitudes of the people that ushered our journey from Punjab to KPK. It was exactly the same. However in my mental map we had crossed an important boundary, into a foreign territory away from the protection of the security of Punjab and into the land of mayhem, torn by acts of terrorism and counter-terrorism.

“Is it even safe to be in these mountains?” I wanted to ask our companions but was too embarrassed to. The embarrassment came not from admitting to others that I felt unsafe in KPK but from the self-realization that all it took for me to feel unsafe was an imagined boundary that has absolutely no significance but administrative demarcation. In another car we were being led by a group of locals from Koniya. For them this part of the land which belonged to KPK was also as much their “local” area as was the land on the side of Punjab. In their understanding of boundaries, maps and borders there was no division of the piece of land that they call their hometown.

Riding on these barren roads I reflected on the arbitrariness of boundaries and borders. For these gypsies who have been traversing these mountains for thousands of years, finding refuge in the warmth of the plains of Punjab during the winters and then perching in the comfort of the mountains during the winters, this division between Punjab and KPK does not exist. Some of them, along with their animals, would continue walking to Afghanistan. The international border, a sacred line in the modern iconography of nationalism just doesn’t exist for them.

The vast reservoir of the lake created by the Chasma barrage was visible from the height that we were on. This is also the season when a lot of migratory birds that have traveled from cold places like Serbia start heading back. For now they were comfortably playing around in the water. Like human gypsies, Serbia, Russia, Mianwali, Pakistan, Punjab, KPK, are all one land to them. Their entire existence, like that of the gypsies, is a story of the defiance of these entities.

Our guides driving in front of us stopped without warning on the side of the road. Zaheer, a cousin of my uncle’s with whom we were staying at Koniya, got out of the car and asked a man who was standing in a field next to the road if Kafirkot was at the top of the mountain. There was a track leading to the top of the mountain from here which eventually got lost within the mountains. There was a group of boys standing at the top of this mountain staring down at us. From here we could only see their silhouettes.

“I think you’ve left Kafirkot way behind,” suggested the Pathan man.

“He doesn’t know anything. Ask those villagers,” suggested my uncle, while the man he was talking about stood right next to him.

“Yeah do that,” he suggested. “I am a traveler myself so I am not the best person to ask for the address.”

Zaheer walking on a small path that divided one agricultural field from another headed towards an isolated house in the middle of the fields. After a while he returned confirming for us that Kafirkot was on the top of the mountain. Leaving our cars on the side of the road we started climbing.

Kafirkot literally means a fort of infidels. One can understand the origins of its name. We were going to the top to see the ancient temples that existed here at the time when Islam spread as the dominant religion around these parts, and these abandoned ancient structures which must once have been the pride of this civilization became symbols of infidels – hence Kafirkot.

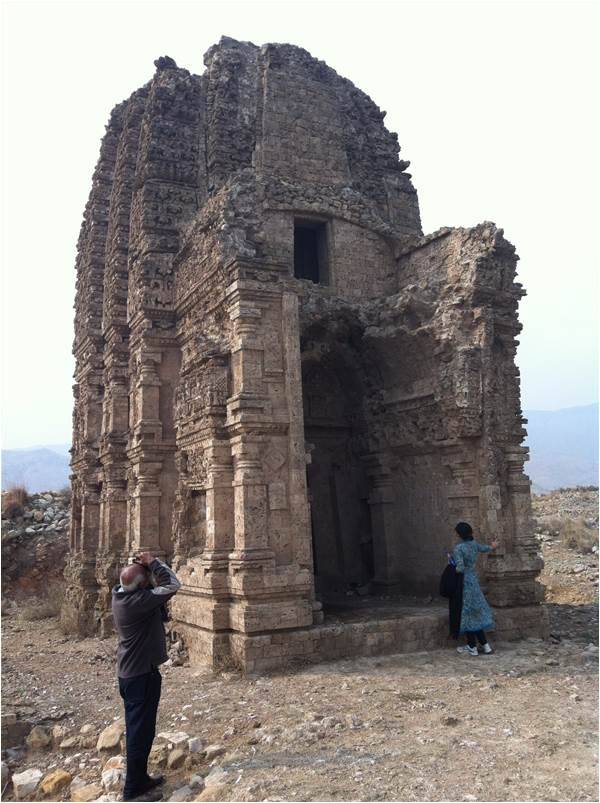

The climb to the top was steep but the path made out of rocks was sturdily built. After a trek of about fifteen minutes the first signs of the fort appeared – a thick boundary wall on the edge of the mountain cliff. We walked into the fort and found ourselves facing ancient temples. The temples were empty but beautifully carved, and constructed in a cone shape, the hallmark of ancient temples. Judging by the way some of these structures were preserved we could tell that the Archaeology Department had been here and had been digging out this place.

A few months earlier I was in Karachi in connection with a research project. There on the island of Manora I came across another ancient temple constructed right on the beach. It too was a cone shaped construction very similar to the architecture of the ancient temple on the top of this mountain here, thousands of kilometers away. It is remarkable how similar these architectural traditions were no matter how far apart.

Given the size of this place it clearly must have been a residential fort, which means that an entire city would have once resided within these boundary walls.

The temples were scattered over a vast area as well. There was one more near another edge of the mountain beyond which was the zigzagging Indus. It was a splendid sight. At the time when this city must have been raised it would have been important to locate a place next to the river but also high enough to not be inundated by it during the monsoons.

“Sir do you think these are Jain temples?” I asked Iqbal Qaiser as he too appeared after a little while taking his time to complete this steep journey. After his successful book on historical shrines Iqbal Qaiser is now working on the Jain temples of Pakistan and he had found in the Jain sources that there were a few ancient temples in the region of Bilot not far from here. However no other sources besides the Jain sources regard these temples as Jain, including the records of the Archaeology Department.

“I am not sure. These look Buddhist,” said Iqbal Qaiser. His analysis was based on pure conjecture. Standing on the steps of one of the ancient temples I called Salman Rashid, one of the most popular travel writers from Pakistan. “These are Hindu temples,” he said. “They are about one thousand years old. There are other ancient temples south from here. Those too are Hindu temples.” He was referring to Bilot which according to Iqbal Qaiser’s research were Jain.

The journey back was much less exhausting but a greater exercise for the calf muscles. Our next destination was the temples at Bilot, about thirty minutes from here and in the district of Dera Ismail Khan.

Haroon Khalid is the author of a travelogue called A White Trail: a journey into the heart of Pakistan’s religious minorities (Westland Publisher, 2013)

Most of these were Balochi gypsies, carrying everything they owned on their beautiful tall camels. The men and the women walked along the road while the children sat on the top of the camels, their blue-green eyes piercing us with disdain for our sedentary lives. As a child I recall my eyes judging them for their perpetual movement. Carrying the bias of the entire settled civilization on my shoulders I used to feel a disdain for these nomadic communities whose entire worldview was different from mine. Being able to look beyond my prejudice today I could admire the elaborate dresses of the women with their colorful borders, and the ethnic caps of the men studded with glasswork.

I was accompanied by my photographer friend Rida Arif, my wife Anam and my mentor Iqbal Qaiser. “I want to become a gypsy,” suggested Rida. It was an idea that resonated with me. The concept of spending one’s entire life on the move has a charm. I imagine a life unburdened by the compulsion of making a living. No alarm clocks, no 9-5.

[quote]The international border, a sacred line in the modern iconography of nationalism doesn't exist for them[/quote]

On our right was the River Indus, the lifeline of the Indus civilization. It was snaking through the plains of the Punjab. “When Indus is a river in Pakistan than why does India derive its name from the Indus?” said Iqbal Qaiser. I smiled politely acknowledging that I had registered what he had said without adding anything more. I wasn’t exactly in the mood for having a conversation. I was enjoying the drive. But what he said was similar to what I was thinking.

Having spent the night at my uncle’s house in the city of Koniya the four of us had left after breakfast to see the ruins of ancient temples not far from the city. Koniya is a small city in the district of Mianwali, which was earlier part of the Bannu district. In 1901, when the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa was carved out of Punjab, Mianwali was made part of Punjab and given the status of an independent district.

Police at a security post stopped us to enquire about our whereabouts just before we reached the bridge on the top of Chashma Barrage with the reservoir of water on one side and the river on the other. The administrative authorities change hands at this point, hence the vigilance. We were now heading into the province of KPK and as we exited from the bridge I noticed an equally eager security check post, this time composed of KPK police officials in blue sweaters.

There was nothing in the geography of the land or the attitudes of the people that ushered our journey from Punjab to KPK. It was exactly the same. However in my mental map we had crossed an important boundary, into a foreign territory away from the protection of the security of Punjab and into the land of mayhem, torn by acts of terrorism and counter-terrorism.

“Is it even safe to be in these mountains?” I wanted to ask our companions but was too embarrassed to. The embarrassment came not from admitting to others that I felt unsafe in KPK but from the self-realization that all it took for me to feel unsafe was an imagined boundary that has absolutely no significance but administrative demarcation. In another car we were being led by a group of locals from Koniya. For them this part of the land which belonged to KPK was also as much their “local” area as was the land on the side of Punjab. In their understanding of boundaries, maps and borders there was no division of the piece of land that they call their hometown.

Riding on these barren roads I reflected on the arbitrariness of boundaries and borders. For these gypsies who have been traversing these mountains for thousands of years, finding refuge in the warmth of the plains of Punjab during the winters and then perching in the comfort of the mountains during the winters, this division between Punjab and KPK does not exist. Some of them, along with their animals, would continue walking to Afghanistan. The international border, a sacred line in the modern iconography of nationalism just doesn’t exist for them.

The vast reservoir of the lake created by the Chasma barrage was visible from the height that we were on. This is also the season when a lot of migratory birds that have traveled from cold places like Serbia start heading back. For now they were comfortably playing around in the water. Like human gypsies, Serbia, Russia, Mianwali, Pakistan, Punjab, KPK, are all one land to them. Their entire existence, like that of the gypsies, is a story of the defiance of these entities.

Our guides driving in front of us stopped without warning on the side of the road. Zaheer, a cousin of my uncle’s with whom we were staying at Koniya, got out of the car and asked a man who was standing in a field next to the road if Kafirkot was at the top of the mountain. There was a track leading to the top of the mountain from here which eventually got lost within the mountains. There was a group of boys standing at the top of this mountain staring down at us. From here we could only see their silhouettes.

“I think you’ve left Kafirkot way behind,” suggested the Pathan man.

“He doesn’t know anything. Ask those villagers,” suggested my uncle, while the man he was talking about stood right next to him.

“Yeah do that,” he suggested. “I am a traveler myself so I am not the best person to ask for the address.”

Zaheer walking on a small path that divided one agricultural field from another headed towards an isolated house in the middle of the fields. After a while he returned confirming for us that Kafirkot was on the top of the mountain. Leaving our cars on the side of the road we started climbing.

Kafirkot literally means a fort of infidels. One can understand the origins of its name. We were going to the top to see the ancient temples that existed here at the time when Islam spread as the dominant religion around these parts, and these abandoned ancient structures which must once have been the pride of this civilization became symbols of infidels – hence Kafirkot.

The climb to the top was steep but the path made out of rocks was sturdily built. After a trek of about fifteen minutes the first signs of the fort appeared – a thick boundary wall on the edge of the mountain cliff. We walked into the fort and found ourselves facing ancient temples. The temples were empty but beautifully carved, and constructed in a cone shape, the hallmark of ancient temples. Judging by the way some of these structures were preserved we could tell that the Archaeology Department had been here and had been digging out this place.

A few months earlier I was in Karachi in connection with a research project. There on the island of Manora I came across another ancient temple constructed right on the beach. It too was a cone shaped construction very similar to the architecture of the ancient temple on the top of this mountain here, thousands of kilometers away. It is remarkable how similar these architectural traditions were no matter how far apart.

Given the size of this place it clearly must have been a residential fort, which means that an entire city would have once resided within these boundary walls.

The temples were scattered over a vast area as well. There was one more near another edge of the mountain beyond which was the zigzagging Indus. It was a splendid sight. At the time when this city must have been raised it would have been important to locate a place next to the river but also high enough to not be inundated by it during the monsoons.

“Sir do you think these are Jain temples?” I asked Iqbal Qaiser as he too appeared after a little while taking his time to complete this steep journey. After his successful book on historical shrines Iqbal Qaiser is now working on the Jain temples of Pakistan and he had found in the Jain sources that there were a few ancient temples in the region of Bilot not far from here. However no other sources besides the Jain sources regard these temples as Jain, including the records of the Archaeology Department.

“I am not sure. These look Buddhist,” said Iqbal Qaiser. His analysis was based on pure conjecture. Standing on the steps of one of the ancient temples I called Salman Rashid, one of the most popular travel writers from Pakistan. “These are Hindu temples,” he said. “They are about one thousand years old. There are other ancient temples south from here. Those too are Hindu temples.” He was referring to Bilot which according to Iqbal Qaiser’s research were Jain.

The journey back was much less exhausting but a greater exercise for the calf muscles. Our next destination was the temples at Bilot, about thirty minutes from here and in the district of Dera Ismail Khan.

Haroon Khalid is the author of a travelogue called A White Trail: a journey into the heart of Pakistan’s religious minorities (Westland Publisher, 2013)