Note: This extract is from the author’s coming autobiography titled Not The Whole Truth: My Life and Times.

By the summer of 1970 I felt I should join the army since I had a feeling that I had no money since Ammi made a fuss about my huge bills in the fruit shop. She did not know about the huge bill I ran for soft drinks from the officer’s mess and the biscuits I consumed in the canteen because they were paid by my father. As I have mentioned earlier, I used to think he did not know about it but this simply could not be possible. He knew and he also recognized my handwriting and I did put my name on the bills, but he just kept quiet. This is something which I did not appreciate at that time though I do now. I do not remember thinking seriously about such a thing as a career nor that I would he considered a failure if I stayed at home playing with younger boys and writing a book on English literature. As an escape from all this, however, foolish, frivolous and childish it may seem now, I did apply for the 7th Graduate Course leading to a permanent commission in the army.

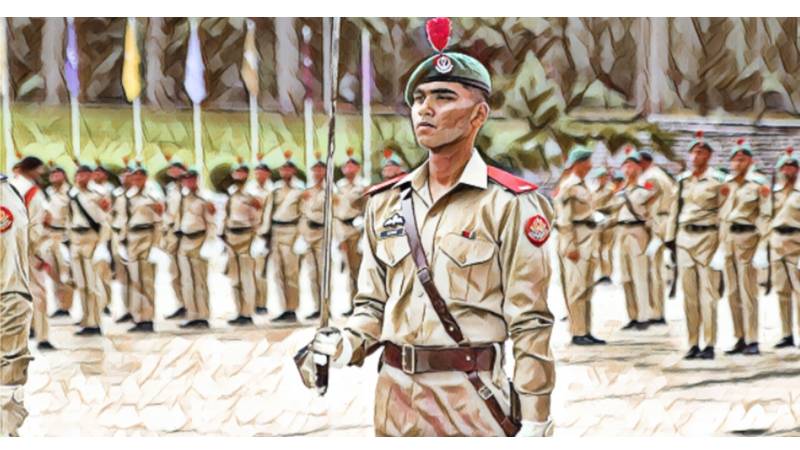

Our first written test was held in Rawalpindi and I passed it with ease. Indeed, a colonel invited me to his house in the evening saying he wanted to talk to me in private about the military career I was choosing for myself. I went to his house and he had a long talk with me earnestly persuading me against joining the army. He said I had a brilliant academic career and it was better for me if I joined the CSP. I still did not know much about the CSP, though as I have written earlier, my mother too had advised me to join it. But I chose what seemed to be the easier path, the one familiar to me, and that was to become an officer in the armed forces. I had to appear for the medical test and the ISSB again and was selected as a gentleman cadet—as army cadets were called. In November 1970 I went down by taxi from my house to the cadets’ barracks—now barracks no longer but impressive four-story high modern buildings—and reported as a cadet. It was extremely cold and the ragging in PMA was much tougher than that in Risalpur or CAE. I was in the Tipu Platoon and a cadet sergeant kept us standing to attention—fall-in as it was called—almost all night. Every half an hour or so the leader, seniorman as he was called, reported to the seniors that his slaves stood at his command. Sometimes we had to change clothes in minutes and very often we were running around in shorts in the freezing winter of PMA. Our course mates, Zaheer and Shameem (both lieutenant colonels later), both avuncular in looks and deportment even at that time, were much annoyed:

‘It is because of these youngsters, these jokers, who love to frisk about in bikinis that we sober people are punished’, complained Zaheer.

‘These youngsters are O.K with the bikinis but we aren’t’, agreed Shameem.

The jokers in question were Ahsaan (major later), myself and Tahir Kardar (lieutenant colonel later) since we looked younger and more lissome and boyish than the others. As for bikinis, that was a calumny since everybody wore shorts. We too struck back by complaining about the uncles (chachus) who did not act their age and who were getting too big for their knickers. But this none-too-polite conversation was overheard by the gestapo and we had a really nasty time. Nobody talked of bikinis or knickers after that.

The seniormen were generally called ‘jittery’ by the others. In the PAF they would have been called ‘panic cases’. Such people carried out all orders to the very letter and were cursed by their course mates. The ones called ‘scroungers’ in the PAF were called ‘dodgers’ in PMA and I was established as one very soon. The reasons were that I reported sick very often avoiding P.T and parade on account of doctor’s orders (Attend ‘B’ or ‘C’) as it was called. I also cared very little about the study schedule often going about with the same books in my satchel for weeks. I never prepared for any English debate or public speaking class because I knew I could write a few points in the class and speak confidently extempore. I also did not pay attention to other subjects though I do not know why because it was much later that I decided not to stay in the army. In the beginning I wanted to do well but I took no pains in my studies or any aspect of training at all. All I wanted was to avoid as much hardship as possible. I was especially bad in map reading, which is absolutely necessary for an army officer, which, I suspect was because of my problem with recognition of places, routes and names. However, why the problem was aggravated was because I paid no attention to the subject, put in no effort into it at all, and was utterly bored by maps. This did not prevent me from enjoying the map reading exercises because they were held in the lovely mountains and picturesque valleys where, while others tried to find the grid reference of their own position, I enjoyed the beauty of the place and idled away the hours. The others who were on a dodging agenda were Qadri and Pervez Qadir, son of Lt. Gen. Altaf Qadir, who became a good friend of mine. One day he confided to me that he would run away from PMA as he could not take the tough life of the army anymore. I told him all about taxis and how one could get away to Pindi and sure enough Pervez Qadir was AWOL (absent without leave) the very next day. Qadri left later but he was perhaps medically boarded out for some reason.

I was very good in the assault course and riding. I took part in both competitions with no preparation or rehearsal and did well in both. In fact, I had just come back from the CMH Rawalpindi when the riding competition was held. I participated and, as my course mates testified, I did very well being excessively cheered by the officers’ children -–read their daughters—when I made the horse jump over the big three-tiered jump. I did not quite believe them because I knew that the said daughters of their imagination never came to this competition anyway. Unfortunately, since I was on Attend C and was not even supposed to get out of my room by doctor’s orders, it was just my good luck that I was not caught and punished for having had the effrontery of taking part in a competition when the doctor had ordered no physical activity for that day.

And once, when we hid the booty since an officer had arrived, two dogs carried it off. But as soon as the officer left, we chased the dogs and got our parathas out of their teeth.

‘Tu ne initiative kiya hae, Kutte! (have you done the Initiative, you Cur!’, we asked the dogs and they had to run away. And even the most fastidious among us ate the food with a ravenous appetite.

One of the lessons I was taught in PMA is worth narrating since it has significance for the way the military dominates this country politically and even economically. It was a lecture and a demonstration on ‘In Aid of Civil Power’. In the demonstration they presented a very smart, ram-rod erect army officer with a clipped English accent who had been assigned to the civil authorities for aid in controlling a riot. He looks around for the deputy commissioner, who is also the district magistrate, who is a shifty, evasive character slouching around in a solar hat. The DC is unable to decide anything in time and the officer, being a pukka officer, pins him down and, after giving him an earth-shaking salute (which we were told is to the DC’s office not the man), asks him to sign an order. After much shillyshallying the DC does so. The officer then opens fire and some people die. The DC panics and asks the officer to stop firing. The latter turns to him with a stony face and says sternly:

‘Now that you have handed over the charge to me, Sir, I am only under my own officers. I will do as they command’.

For me, who knew nothing about the reality of my country, it was further confirmation of my view that the real officers were army officers—and by grudging extension PAF and naval ones—but people like DCs were not really pukka sahibs. I am sure my other course mates knew better about the power of civilian officers but, since we never discussed such matters, it was only much later in QAU that I discovered the reality and understood why so many of my students wanted to join the DMG and the police.

I did not mind the tough life of PMA and the physical exercise did not bother me though it turned out that I was not good in either P.T or drill. I was, of course, very good on horseback and I did not mind running cross country, going on exercises involving long treks over mountains or firing. I loved socializing very much. In time we became senior. The first termers, 48th Long Course, were our juniors. I did not give anyone physical punishment nor did I use the invectives and swearing which is a normal characteristic of PMA language (the sergeant major’s lingo). My form of ragging was to listen to songs from the juniors or to take them to the canteen to feed them on sweets. I had a number of friends including Ali Raza (46th), who became a captain in the infantry and was an army squash champion, and Mahmud Sultan (Salty) (45th), who retired as a brigadier, who had been my companions as boys in PMA. As for intellectual company there was none. My course mates, having already passed their B.A. and being older than the boys who had joined after intermediate (12 years of schooling), tended to stay together. I, on the other hand, made friends among other courses too since at that time I was more at home with boys who spoke English habitually like myself. Some of these boys, being both younger and good-looking, were categorized as cheekus by my course mates. My Bengali course mate Mustafa would tease me about this ‘pouch ammunition’ (i.e. ammunition kept for an emergency). He talked as if there were many such friends though, in reality, he knew nobody else at all. Besides the affinity created by fluency in English, I used to go for riding which was another place where I met cadets of different courses. My course mates never went for riding either so they did not meet my younger friends. The majority opinion among my Bengali friends, at least with those on whom I was on joking terms, was that I kept the real ammunition, presumably my girlfriends, up in the officers’ colony. But since my parents left PMA I never went to the officers’ colony and, in any case, there was no girlfriend anywhere at all. I, however, only laughed about such innuendoes not bothering to contradict them.

I also frequented another club, though it was not called one, through my careless disregard for orders. This was the punishment—restrictions and extra drill—club which my course mates avoided being extremely cautious. Sometimes for not shaving properly, and at others for being improperly dressed, I was put on restrictions. Cadets on restrictions could not watch movies, could not ‘book out’ (go home or to Abbottabad) and, to put the crowning touch to this state of affairs, had also to go for a very tough form of drill which was called extra drill. The only good which came out of this extra drill was that one made friends with delinquents of one’s own kind some of whom later became generals in the army. Though, apparently I had many friends, in fact I formed no deep friendship with anyone in PMA. Possibly this was because the bond of close comradeship one has for one’s course mates had already been formed with my PAF course mates. So I was the outsider in my course though I never said this for fear of hurting my course mates who were very cordial and friendly towards me. I loved to help my course mates and cooperated with them in everything. When we went on the five-day, commando style exercise called ‘initiative’, I carried the machine gun more than others. We walked scores of miles before we were allowed to sleep and even then some of us had to be on duty. The others collapsed with exhaustion and slept but I was plagued with insomnia even at that age and tossed and turned even after my sentry duty. Hence, I offered others that I would do their duty for some time and they were most obliged to me. Moreover, the mountainous ways, which everyone hated, I knew and loved so well. So, I kept going on cheerfully though I could not sleep much at night.

We ate from the nearly villages and water was like treasure which few wanted to share. About the food we bought from the villages, there is an interesting anecdote. It was strictly against orders since we were given dry rations which we were supposed to cook. To make our loads lighter we threw this away in the beginning and carried biscuits, nuts and chocolates instead. But since these could not last long, we had to buy cooked food. And what a feat it was: parathas (unleavened bread fried in oil or clarified butter), eggs and sometimes fried or boiled potatoes! And once, when we hid the booty since an officer had arrived, two dogs carried it off. But as soon as the officer left, we chased the dogs and got our parathas out of their teeth.

‘Tu ne initiative kiya hae, Kutte! (have you done the Initiative, you Cur!’, we asked the dogs and they had to run away. And even the most fastidious among us ate the food with a ravenous appetite.

One evening, on the last day of the exercise, they made me the leader of my platoon. We were supposed to arrange a mock ambush on a narrow mountain road. I did this so well that the platoon commander, Major Basit, beamed. My platoon mates said that I could become a ‘bloody general’. It was the highest praise anyone gave to good performers and, for once, this is what some of my platoon mates conceded. But the sober ones added: ‘if he only stops dodging’. This, everybody pointed out was a big ‘IF’. And soon enough they got proof of my incorrigibility since, as soon as the officers withdrew, I called a council of war in the Tipu platoon.

‘We will go back in the trucks,’ I suggested.

‘And if we get caught they will drum us out of PMA’, countered the wise ones.

‘We won’t be caught. Just get down where I tell you to get down. I know this area like the back of my hand’, I told them. They countered with rather rude remarks about the ‘back of my hand’ but I was adamant and used a confident tone.

Everybody was sceptical but then PMA was about thirty miles away and nobody fancied the all-night weary trudge to it. So we sat in the trucks crouching down in the dark and the trucks rumbled down the mountains and into the Abbottabad valley. Near Supply I got them stopped and we got out. I took the whole platoon to a small shack which supplied endless cups of tea, eggs, biscuits and parathas. So cheered up were we that we sang and even danced and so passed the night. Late in the morning we crawled back to PMA being careful not to arrive first. We were never caught and ‘Tipu Platoon’s secret’ was created that day.

(to be continued)