Alexander the Great, Genghis Khan, and Napoleon Bonaparte – if people in a random exercise were asked to name the greatest military commanders in world history, chances are they would name one of these three, if not all of them. Of course, there are also other famous military commanders in different times and cultural zones.

However, few would name perhaps the greatest military commander of them all, Khalid Bin Walid. No doubt Muslims would name him and there are many Muslims named after him, but non-Muslim history books and commentary tend to ignore Khalid.

In his acts of personal boldness and physical courage in the heat of battle, he reminds us of Alexander the Great. In the coordination of his battalions and the speed and accuracy with which they met at distant designated places, he was like Genghis Khan and his swift horsemen. In his ability to move his battalions strategically and with lightning speed, he was like Napoleon in his early military career.

Besides, Alexander’s conquests disintegrated on his death, Genghis’ empire split into separate kingdoms after he died, and Napoleon’s career ended ignominiously after his disastrous invasion of Russia and defeat at Waterloo.

In contrast, Khalid bin Walid, who was either in command or participated in some 100 military engagements, emerged triumphant in every battle and the impact of his victories can still be seen in the regions where he fought and triumphed. Some of his battles were so fierce that, as he famously observed after one of them, he broke seven swords.

Professor Roy Casagranda, a professor of Government at Austin Community College and its Middle East Affairs expert, has declared that Khalid was “possibly the greatest general in human history. He was essentially undefeated and did the impossible over and over again.” (In his lecture on Salahuddin Ayubbi available on YouTube). General Akram of the Pakistan army in his biography of Khalid described him as the greatest general in history. Dr Omar Suleman, an Islamic scholar based in the USA, in his lecture on Khalid bin Walid, has called him the greatest Muslim general in the history of Islam after the Holy Prophet (PBUH).

Muslims admire Khalid to the point of looking at him as a superhero. After all, the Prophet of Islam himself (PBUH) gave Khalid bin Walid the title of The Sword of Islam. Abu Bakr (RA) said of Khalid bin Walid, “Women will no longer be able to give birth to the likes of Khalid bin Al-Walid.”

Another typically courageous, almost reckless, move was Khalid’s march through the vast inhospitable desert between Iraq and Syria. It was best to take his army around the desert and avoid its dangers. But Khalid plunged in and when his troops were in danger of dying of thirst, he revealed the trick he had up his sleeve

The creation of a new world order

Let me explain the significance of Khalid bin Walid’s military success. In the earliest years of Islam, when it had barely consolidated in Arabia itself, an exercise in which Khalid played no small part, Khalid led a small army and first defeated the Persian empire and then turned round and challenged and defeated the Roman empire, often referred to as the Byzantine empire. Within a year, Khalid had effectively shattered the two most powerful empires of his time. His victories announced the arrival of a new player on the world stage. The world would never be the same.

Of course, to highlight Khalid is not to ignore the other great military commanders of Islam. There are, for example, many other heroes in Islamic history: the list must start with the Prophet of Islam himself (PBUH), the role model for all Muslims, there is Hazrat Ali (AS) the warrior-scholar, cousin of the Prophet (PBUH) and fourth caliph of Islam; General Tariq who conquered Spain, Sultan Salahuddin who defeated the Crusaders and retook Jerusalem, there is General Baybars who defeated the Mongols and halted their progress in the Middle East, and Emperor Babar who conquered India and founded the Mughal dynasty, considered one of its most illustrious dynasties.

By the time the Prophet (PBUH) passed away in 632 almost half of the Arabian peninsula had come under Islamic rule. For the first time in history central authority had formed in the peninsula. The Prophet’s successor, the caliph Abu Bakr (RA), placed Khalid in command of his army to subjugate the tribes in the north- east who were challenging the newly formed state.

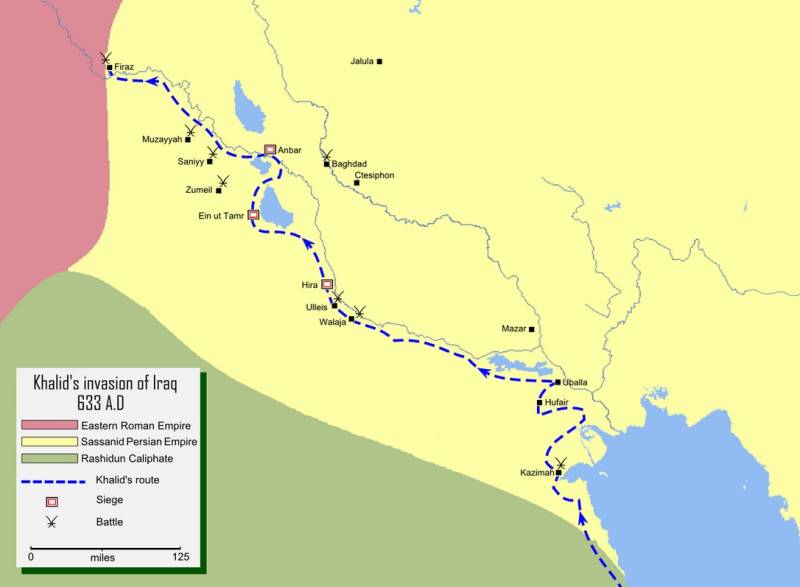

In a series of lightning military encounters called the Ridda, Khalid succeeded in pacifying these areas. Perhaps acting on higher orders, perhaps on his own initiative, Khalid maintained the military momentum and crossed into the Persian empire; after defeating the Persians he aimed for the Roman empire.

Throughout his military adventures Khalid had to encounter issues of the treatment of prisoners, the discipline of his soldiers, the management of loot and the administration of the conquered territory. He had clear instructions from Abu Bakr (RA), who was one of the first rulers in history to lay down the rules of war. Instructed by the Prophet (PBUH) himself, Abu Bakr (RA) ordered that his military commanders at all times act with moral integrity and compassion: women and children, priests, houses of worship, were not to be harmed. Even trees and foliage were not to be damaged. Prisoners were to be treated with humanity and neither physically tortured nor subjected to mental humiliation. Abu Bakr (RA) also banned mutilation.

It is worth reminding the reader that the Prophet’s (PBUH) favourite uncle Hamza, and one of the prominent members of the Quresh tribe, had been killed and his body mutilated in an early battle. It had left the Prophet (PBUH) bereft at the manner of his uncle’s death.

The inhabitants of the defeated cities would invariably be pleasantly surprised at the attitude of the victorious Muslim commanders. They would say, according to Professor Roy Casagranda, the custom in this area has been to take the women and children as slaves, kill the men and loot the houses and the shops. Often the enemy burnt the town. In contrast, Muslims were not allowed to do any of these things, on the contrary they were constantly reminded by the caliph himself to never compromise on their sense of compassion and justice. I hasten to add that while these are ideal rules, in reality many commanders have flouted them –invariably earning the wrath of their own people.

The Muslim commander even in victory had to show restraint, compassion and humility. He could not indulge in the kind of blind blood orgy Alexander ordered at Persepolis or Genghis exhibited with his huge pyramids of skulls made of his enemies’ heads.

After the caliph Umar (RA) arrived in Jerusalem, he promised Sophronius, the Christian Patriarch, that the Christian community would be protected under Muslim rule. The caliph asked to visit the site of Solomon's temple and cleared away the garbage accumulated there. When the caliph asked to meet the Jewish community Sophronius felt embarrassed and said they had been expelled from Jerusalem. The caliph ordered that they be allowed back. The caliph then thanked Sophronius for arranging mats etc for Muslim prayers at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, the spot where Jesus was crucified and buried. If I pray here, he explained, Muslims may claim it later as a mosque. They found a spot for prayer outside the Church and sure enough a mosque was built there which is still extant. Sophronius was left amazed at the behaviour of caliph Umar, perhaps comparing his simplicity, compassion, and humility to the pomp and arrogance of the Roman emperors.

Khalid’s background

Khalid bin Walid was the son of one of the most influential leaders of the Banu Makhzum clan that dominated the economic and political life of Makkah. The clan had money, social influence, and political power. It looked down on its rival clan, the Banu Hashim. When the prophethood was announced from the Banu Hashim, rivalry between the two clans grew worse. The Banu Makhzum could not accept that someone from a weaker clan would be nominated as the Prophet of Islam (PBUH). That is why the Prophet (PBUH) prayed so hard for Umar bin Khatab, a leading member of the Banu Makhzum, to join his embattled Muslim community.

One of the momentous developments in the early days of Islam was the conversion of Umar (RA). Khalid bin Walid was a younger cousin of Umar and like him a tall, well-built, and powerful man; but unlike Umar he did not respond to Islam. On the country, he played a key role in the early battles against the Prophet (PBUH) and his brilliance was on display at the battle of Uhud which almost turned into a disaster for the Muslims. But shortly afterwards Khalid bin Walid became a Muslim and joined the battle of Mukta against the Roman army, much bigger and better trained than the Muslims. Three Muslim commanders were killed. When Khalid was given command, he managed to retreat and save the Muslim army. Had it not been for the new Muslim convert, the Muslim army would have been massacred.

When the Prophet (PBUH) passed away in 632, Abu Bakr (RA), recently appointed caliph, sent Khalid on a mission to the eastern parts of the peninsula to promote Islam. Khalid would be key to converting all of Arabia to Islam in what are called the battles of Ridda. Almost in an unbroken military manoeuvre Khalid went on and crossed into the Persian and the Byzantine empires.

In his greatest triumphs, Khalid was fighting two established empires, both massive in size with large populations, resources, and an ancient history. Both had been established over the last centuries although they had seen ups and downs. Khalid faced well trained, well-armed, and well-fed armies invariably 3 to 4 times in size compared to his. Besides, Khalid’s smaller army came from an area with few resources, no rivers, and no major cities.

In the battles with the Persian empire and then the Romans, Christian Arabs and Armenians and others fought against Muslim Arabs, although it is important to point out that the glory days of the Romans and Persians were long past, and they had wasted their resources fighting each other.

Khalid bin Walid’s battle with the Roman army led by Vahan, the supreme commander and brother of the Roman emperor Heraclius, at Yarmuk lasted for six full days of non-stop fighting. It was a brutal and fierce military engagement, and the stakes could not have been higher.

The battle that changed the world

Vahan, impressed by Khalid’s boldness, attempted to reason with him. He requested a meeting and pointed out the disparity in the quality of the two armies and their size. The Muslims were outnumbered and in contrast the Roman soldiers were in shining armour and looked trained and well fed. A celebrated exchange followed between the Roman commander and his Muslim counterpart. After Vahan failed to persuade Khalid to take his soldiers back to where they came from as they faced certain annihilation, Khalid replied: "You don’t understand the nature of my soldiers. They are in love with death for their cause, as your soldiers are in love with life, and nothing will persuade them to retreat."

“The encounter at the Yarmuk thus deserves to be ranked among the most important battles of World History,” writes the scholar John W Jandora in his article “The Battle of the Yarmuk: A Reconstruction” (Journal of Asian History, 1985): “Despite its significance, however, the battle has yet to be analysed from a military perspective. Military historians have neglected it, while Orientalists have been frustrated by the fragmentary and inconsistent nature of the sources. The latter have generally tended to view the Arabs’ success as the result of religious fervour. It is not plausible, however, that religious fervour alone could have stopped the Byzantine heavy cavalry.”

Khalid’s victory at Yarmuk changed the world. At Yarmuk, Khalid deployed his characteristic tactics with supreme confidence and boldness: Speed and precise strategic and tactical manoeuvres while watching the enemy for weak spots and hitting the enemy where they least expected it. Khalid was a master at creating illusions, for example, deploying the same soldiers going around the mountain and coming back or soldiers at night creating mini fires and walking about to show that they had more soldiers than in reality they had. Not only Muslims but non-Muslims also saw the early victories of the Muslims as miraculous.

Khalid’s boldness

Khalid’s boldness knew no bounds. As commander of his army, he chose to also nominate himself as the warrior to fight the leading warrior from the opposing army as was the custom in those days. It was a risky decision. If he was killed his army would be left without a leader and lose the battle. Indeed, in a critical battle against the Persians the commanding general conceived a cunning plan for just such a contingency. The night before the battle calculating where the clash of the two warriors was to take place, the Persian had twelve of his best warriors dig themselves just beneath the surface with straws to breathe through. When the fight began the next morning, these warriors jumped out and attacked Khalid. Khalid’s cousin saw what was happening and rushed to the aid of his kin. Together the two dispatched the thirteen Persian warriors, but it had been a close call.

Another typically courageous, almost reckless, move was Khalid’s march through the vast inhospitable desert between Iraq and Syria. It was best to take his army around the desert and avoid its dangers. But Khalid plunged in and when his troops were in danger of dying of thirst, he revealed the trick he had up his sleeve. He had filled several camels beforehand with water so midway in the march he had them killed for the water they had stored in their humps. Hugh Kennedy in The Great Arab Conquests: How the Spread of Islam Changed the World We Live In (Philadelphia: Da Capo Press, 2007) states that “Khalid’s march across the Syrian desert…has been enshrined in history and legend: Arab sources marvelled at his endurance; modern scholars have seen him as a master of strategy.” Indeed, the desert adventure featured heavily in Islamic accounts of the march, with the scholar Fred M. Donner noting that it “fired the imagination of the chroniclers, who almost without exception include some version of it in their accounts of the conquest” (The Early Islamic Conquests, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981). The march was according to Kennedy “a memorable feat of military endurance…his arrival in Syria was an important ingredient of the success of Muslim arms there.”

Historian Moshe Gil (A History of Palestine, 643-1099, Translated by Ethel Broido, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997) calls the march “a feat which has no parallel” and a testament to “Khalid’s qualities as an outstanding commander” in “his excellent organising ability and his skill at manoeuvring on the battlefield.”

At one point, the Romans and the Persians contemplating Khalid’s victories over their armies with disbelief decided to bury the hatchet and form a united front against Khalid. Arabia had never been colonised or conquered even by its two sprawling and long-lasting imperial neighbours, the Persian or Sassanid and the Byzantine or Roman. So, when suddenly out of the Arabian deserts a ragtag army turned up to challenge one and then the other empire it left everyone scratching their heads.

Facing an army of some 150,000 troops at Firaz on the border between the Roman and Persian empires at the Euphrates river, Khalid mobilised his army of 15,000. Khalid’s opposing army consisted of Romans, Persians and a large percentage of Christian Arabs. In the battle that followed, Khalid destroyed the united army which lost 50,000 men. Khalid’s loss was some 200. The odds Khalid faced and the spectacular nature of his victories appear almost unbelievable-—yet we are assured by historians that they are true.

Contemplating the size of the enemy’s army in the last battle and the slim chances of his survival, Khalid promised God that if he won, he would immediately perform the Hajj. If he became a martyr he believed he would have a good day. When he was victorious, Khalid immediately arranged for the fastest horses and galloped off to Makkah where he performed the Hajj all the while disguised in heavy robes. But he was seen and when he returned, he found a letter from the caliph Abu Bakr (RA) waiting for him. Do not try this again, it warned him. Shortly afterwards Abu Bakar died and Umar, Khalid’s first cousin, was declared caliph.

Khalid had another famous encounter with the Persians, when he had some 15,000 troops and faced 60,000 Persians divided into three armies. Khalid divided his troops into three groups of 5,000 each and then sent them out to meet at the site he calculated the Persians would be camped. All three of his groups met at the right time and the right place and in nighttime attacks destroyed the Persians. He repeated this manoeuvre two more times. As any military analyst would confirm this is an almost impossible manoeuvre to pull off successfully.

In the meantime, Khalid’s victories against the Romans had given the Arabs control of Jerusalem, where the leaders of that city waited to hand over its keys to Umar (RA), the caliph of Islam. Rather than wait for Umar to arrive Khalid’s advisers suggested that, as he looked so much like his cousin, they would present him as the caliph. Unfortunately for Khalid someone in Jerusalem recognised him. In the meantime, Umar who had just taken over from Abu Bakr (RA) as caliph ordered the immediate demotion of Khalid and that he be brought before him tied with his own turban. Khalid faced whatever complaints there were against him and was exonerated. He was then allowed to return to his army unit although in his new capacity as an ordinary soldier.

When Umar (RA) ordered Khalid to be removed from his command as head of the Muslim army, he replaced him with Abu Ubaida, a senior, gentle and respected figure who was tipped as a possible successor to the Caliph Umar himself. But the Muslims were still engaged in different battles with the Romans. Abu Ubaida to his credit called for a meeting of the commanders and asked them who they would prefer to lead them: Khalid or Ubaida? They unanimously said Khalid. Ubaida with some relief sighed, me too.

There has been extensive commentary on Umar’s motivation in dishonouring a Muslim hero at the height of his powers in such an ignominious manner. Umar according to Muslim mythology now feared that Khalid was becoming too big for his boots and people would attribute his success on the battlefield to himself rather than to God. Perhaps there was an underlying tension between the cousins, what anthropologists describe as agnatic rivalry.

So Khalid, arbitrarily stripped of command and fresh from his victories on the battlefield, went quietly home to retirement. He was younger to the Prophet (PBUH) and died in 642 not long after the Prophet passed away.

There is a story told of Khalid when someone visited him on his deathbed, he found him in tears. Khalid said that there was not even the space of a single finger on any part of his body which was not wounded and injured in battle and yet here he was dying in bed. He would have preferred to die in battle. But the Muslims said how could the sword of Islam, the title given to him by the Prophet (PBUH), be broken in battle.

We need to point out that Khalid has his detractors. Many Iranians are hostile because they believe he was responsible for overturning their ancient Persian Sassanid empire and introducing Islam to their culture; in short, they see him as a symbol of Arab Sunni imperialism. Orientalist scholars dislike the fact that he was a military genius and there are various clearly concocted theories that in fact many of his victories did not even exist.

Considering the scale of Khalid’s achievements and the legendary status he has acquired in Islam, I find it curious that there are such few full-fledged biographies or films about him. There are of course scattered references (for example, Roy Casagranda’s unabashedly enthusiastic romp which is available on YouTube) and some articles (for example John Jandora on the Battle of Yarmuk and its significance). But nothing like the flood of books and movies on Alexander and Napoleon. Professor Roy Casagranda blames this lack of attention to Khalid on what he calls the “racist bias” of Western history which only thinks of Western leaders as the “cool guys.”

General AI Akram wrote a standard book on the Arab general called Khalid bin Walid- The Sword of Allah after the author travelled throughout the Middle East going over the battlefields of the Arab warrior. General Akram, one of the most distinguished Pakistani soldiers, stated that in his estimation Khalid was the greatest general in history. I had the pleasure of meeting the general in Peshawar and recall his dedication to and passion for the study project on Khalid bin Walid which he was working on.

Muslims are prominently being persecuted across the planet. We see heart-breaking images of men, women and children being mercilessly killed on our TV screens. Words such as genocide and ethnic cleansing have been reduced to meaningless semantics. The silence of the leaders is deafening and is only compensated for by the unrestrained roar of ordinary people across the planet who are in anguish and saying enough.

Khalid’s relevance today

What lessons does Khalid’s life have for us today? Surely the world does not need another military warrior, however much his undoubted military brilliance, his unmatched courage in battle, his dedication to upholding the rules of war, his humility and his complete faith in his cause are inspiring. When Muslims face so many challenges across the planet, Khalid’s success, his character and his nobility are a shining example to inspire and give heart to them. Of course, Islam is a complex and rich culture; for every Khalid it has also produced a Rumi and an Ibn Arabi.

The day of the men of swords and lances may have passed. Our world, beset as it is with problems of poverty, global warming, and conflict, surely needs to be led by men and women advocating Rumi’s vision of peace and harmony with Khalid’s boldness and commitment. Just as Khalid stands resolutely defending his community, Rumi reaches out and embraces the world. The Muslims need to understand what these icons represent in our own times to decide how to proceed.

Today, Muslim leadership is confronted with a moral dilemma: how to find the delicate balance between the two poles on the spectrum: inclusivity at one end, martial activism at the other. In order to unravel this complex conundrum, we must turn to our own history. That is where Khalid and his story become relevant.

Muslims need to ask themselves two related questions: why has the Muslim world failed to produce Khalid bin Walids today? Should the emphasis be on producing Rumi or Khalid?

Both Muslims and non-Muslims need to watch the hands of the doomsday clock for the answers: it has moved dangerously close to midnight. The world needs to be thinking of urgently solving global problems like climate change and resolving the bloody conflicts around the world. As if anticipating such problems, the wise leaders of seventh century Arabia enunciated the rules of war. What legacy will the leaders of our world leave for their children and grandchildren?