In 1966, students of the University of Strasbourg and the Situationist International in France wrote a pamphlet that would later prove to be a monumental document on education and student life. The pamphlet started off strong: “The student is the most universally despised creature in France, apart from the priest and the policeman.”

In contemporary Pakistan it is common to see policemen and traffic wardens harassing students on the roads. Students, in turn, try to induce pity by merely stating their identity. “Please let us go, we are students,” they generally plead. As if being a student is sufficient to explain their misery. To live in an age where students only have to reiterate the fact that they are students to communicate their poverty and seek relaxations is testimony to a grave predicament. It shows that 50 years after the students of France wrote that pamphlet, the statement still holds true for students, especially of Pakistan.

More than three decades have passed since the state formally banned all student organizations. Gone are the days when students were central stakeholders in political processes, when their collective power was enough to topple dictators, and where they were the flag bearers of progressive change in the country. What we see now is an abandoned, alienated and depoliticised mass, whose political ambition is, at best, to become frontline sloganeers of leaders who actively seek to keep their power for their own interests.

A lot could be written about the problems faced by students today, about their alienation, volatility and degradation. But a fundamental question that should precede any analysis of the situation is this: What does it mean to be a student in Pakistan in 2018? Ideally, no one would be more suited to answer this question than the students themselves. But owing to the state’s long term policy of silencing, the students are simply not empowered enough.

Since students lack the platforms as well as the voices to answer how the youth of this country sees itself, the answer to the question may be found in a detailed analysis of the relationship of a student with the educational structure.

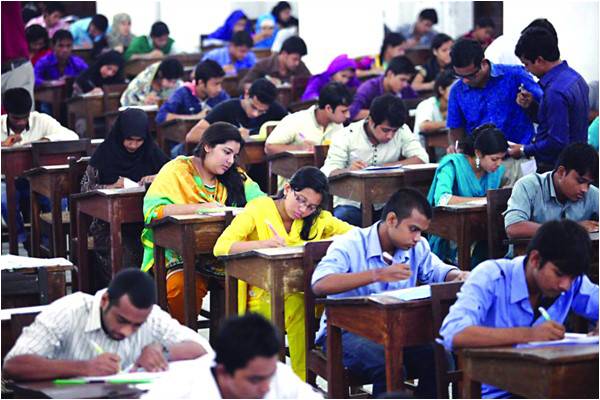

The relationship of a student with the university is perhaps more profound than with the home, since students spend the better part of their day at campus and, that too, in an attempt to make it as productive as they can. Campuses in Pakistan, however, present a picture is closer to a factory. If the work of a worker is characterised by their alienation with the fruit of their labour, the same is the case with students whereby their academic life is comprised of meaningless assignments, pointless mid-terms and lengthy research that has nothing to do with the life we see around us. The courses taught at public sector universities are outdated and it has been years since they were revised.

For instance, in the campus where I study, Political Science courses start from the customary, one-dimensional praise of the Movement for Independence, and through a strict, obsolete and mathematical study of imaginary political systems, concludes by thanking divine powers for blessing us with the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Campuses with more than 10,000 students have inactive or non-existent research centers which neither have funds, nor a word of motivation for students who dare to attempt research outside the scope of mainstream topics of study.

The most interesting, and perhaps the most painful, thing about this coercive relationship is that even though campuses are far from what they should be, most of our youth dreams of having a chance to study there. At best, not more than 20 percent of the youth has ever been accommodated within these universities. This has given way to more than 100 fake campuses across the country which are sucking finances out of students who find, after wasting precious years of their lives, that they would get no degree at the end.

The government, rather than fighting this, has been a partner in crime. In continuation of its tradition at pulling out of the crisis rather than rectifying it, the government cut off the Higher Education Commission’s budget to almost half. This was followed by the initiation of an aggressive privatisation scheme in which private managements, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and investment parties were incentivised and private stakeholders were awarded sub-campuses of public universities.

The government used campuses like that of Imperial College of Business Studies, Lahore to loot millions of USAID scholarship money at the expense of students from Afghanistan. A similar crisis unfolded at Bahauddin Zakariya University’s Lahore Campus where students were told after four years that they had been fooled. Almost all sub campuses affiliated with major universities are mere money-making entities where degrees are sold without any quality assurance, where students are clients, these sub-campuses are service providers, and education a commodity.

No public sector university in Pakistan has implemented any extensive anti-harassment guidelines formulated by the HEC. This means that female students face harassment on a daily basis. They are slut-shammed, name-called and are guilty until proven innocent if they do decide to speak to the administration. They are imprisoned in hostels and in universities like UET Taxila, not allowed to stay out after 3:30 pm in the day. Even in co-education institutions, students of the opposite sex are not allowed to intermingle and the administration even goes to the extent of banning girls from talking to boys in university buses. Due to our patriarchal traditions, a female generally relates with university as an attempt at living whatever she can before she is sentenced for life through marriage. But even these four years are marred with constant abuse by peers as well as the faculty, which generally goes unchecked. After all, who was the last female vice chancellor of a major university in Pakistan?

For a student belonging to the less privileged provinces, university life becomes a daily lecture on how to be a Pakistani. An emphasis is on the fact that they can never be Pakistani enough, but that they still have to try their best. This is reflected when Baloch Day celebrations are attacked, when the Pashtun identity is appropriated with terrorism and more than 200 Pashtuns are charged under terrorism laws, and when Baloch students have to take special permissions to wear their cultural dress in university premises.

The fundamental contradiction of a student’s relationship, however, lies in the system’s active attempt at demonising collective action. Students are taught and coerced to stay away from politics, and such propaganda has been carried out to an extent that students are now afraid of their own organization. Their study circles are termed as conspiracies against the state and any attempt at politicising or protesting for the oppressed communities are met with severe disciplinary action. In a few notable institutions, wearing shalwar kameez is ridiculed by head of departments on account of being ‘uncivilized’ and some learned professors even go to the extent of telling Pashtun students to stop talking to each other in Pashto.

The students of a public sector university in Pakistan may be characterised as workers who pay for their own labour, or clients who buy degrees to merely prolong unemployment for four years. They study in a system when they are alienated and indulged in cut-throat competition against each other and where the life they live on campus is far from what they imagine. The day must come soon when the students are empowered to organise, understand, and redefine their relationship with education so that they can truly achieve the best with their potential.

In contemporary Pakistan it is common to see policemen and traffic wardens harassing students on the roads. Students, in turn, try to induce pity by merely stating their identity. “Please let us go, we are students,” they generally plead. As if being a student is sufficient to explain their misery. To live in an age where students only have to reiterate the fact that they are students to communicate their poverty and seek relaxations is testimony to a grave predicament. It shows that 50 years after the students of France wrote that pamphlet, the statement still holds true for students, especially of Pakistan.

More than three decades have passed since the state formally banned all student organizations. Gone are the days when students were central stakeholders in political processes, when their collective power was enough to topple dictators, and where they were the flag bearers of progressive change in the country. What we see now is an abandoned, alienated and depoliticised mass, whose political ambition is, at best, to become frontline sloganeers of leaders who actively seek to keep their power for their own interests.

A lot could be written about the problems faced by students today, about their alienation, volatility and degradation. But a fundamental question that should precede any analysis of the situation is this: What does it mean to be a student in Pakistan in 2018? Ideally, no one would be more suited to answer this question than the students themselves. But owing to the state’s long term policy of silencing, the students are simply not empowered enough.

No public sector university in Pakistan has implemented any extensive anti-harassment guidelines formulated by the HEC

Since students lack the platforms as well as the voices to answer how the youth of this country sees itself, the answer to the question may be found in a detailed analysis of the relationship of a student with the educational structure.

The relationship of a student with the university is perhaps more profound than with the home, since students spend the better part of their day at campus and, that too, in an attempt to make it as productive as they can. Campuses in Pakistan, however, present a picture is closer to a factory. If the work of a worker is characterised by their alienation with the fruit of their labour, the same is the case with students whereby their academic life is comprised of meaningless assignments, pointless mid-terms and lengthy research that has nothing to do with the life we see around us. The courses taught at public sector universities are outdated and it has been years since they were revised.

For instance, in the campus where I study, Political Science courses start from the customary, one-dimensional praise of the Movement for Independence, and through a strict, obsolete and mathematical study of imaginary political systems, concludes by thanking divine powers for blessing us with the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Campuses with more than 10,000 students have inactive or non-existent research centers which neither have funds, nor a word of motivation for students who dare to attempt research outside the scope of mainstream topics of study.

The most interesting, and perhaps the most painful, thing about this coercive relationship is that even though campuses are far from what they should be, most of our youth dreams of having a chance to study there. At best, not more than 20 percent of the youth has ever been accommodated within these universities. This has given way to more than 100 fake campuses across the country which are sucking finances out of students who find, after wasting precious years of their lives, that they would get no degree at the end.

The government, rather than fighting this, has been a partner in crime. In continuation of its tradition at pulling out of the crisis rather than rectifying it, the government cut off the Higher Education Commission’s budget to almost half. This was followed by the initiation of an aggressive privatisation scheme in which private managements, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and investment parties were incentivised and private stakeholders were awarded sub-campuses of public universities.

The government used campuses like that of Imperial College of Business Studies, Lahore to loot millions of USAID scholarship money at the expense of students from Afghanistan. A similar crisis unfolded at Bahauddin Zakariya University’s Lahore Campus where students were told after four years that they had been fooled. Almost all sub campuses affiliated with major universities are mere money-making entities where degrees are sold without any quality assurance, where students are clients, these sub-campuses are service providers, and education a commodity.

No public sector university in Pakistan has implemented any extensive anti-harassment guidelines formulated by the HEC. This means that female students face harassment on a daily basis. They are slut-shammed, name-called and are guilty until proven innocent if they do decide to speak to the administration. They are imprisoned in hostels and in universities like UET Taxila, not allowed to stay out after 3:30 pm in the day. Even in co-education institutions, students of the opposite sex are not allowed to intermingle and the administration even goes to the extent of banning girls from talking to boys in university buses. Due to our patriarchal traditions, a female generally relates with university as an attempt at living whatever she can before she is sentenced for life through marriage. But even these four years are marred with constant abuse by peers as well as the faculty, which generally goes unchecked. After all, who was the last female vice chancellor of a major university in Pakistan?

For a student belonging to the less privileged provinces, university life becomes a daily lecture on how to be a Pakistani. An emphasis is on the fact that they can never be Pakistani enough, but that they still have to try their best. This is reflected when Baloch Day celebrations are attacked, when the Pashtun identity is appropriated with terrorism and more than 200 Pashtuns are charged under terrorism laws, and when Baloch students have to take special permissions to wear their cultural dress in university premises.

The fundamental contradiction of a student’s relationship, however, lies in the system’s active attempt at demonising collective action. Students are taught and coerced to stay away from politics, and such propaganda has been carried out to an extent that students are now afraid of their own organization. Their study circles are termed as conspiracies against the state and any attempt at politicising or protesting for the oppressed communities are met with severe disciplinary action. In a few notable institutions, wearing shalwar kameez is ridiculed by head of departments on account of being ‘uncivilized’ and some learned professors even go to the extent of telling Pashtun students to stop talking to each other in Pashto.

The students of a public sector university in Pakistan may be characterised as workers who pay for their own labour, or clients who buy degrees to merely prolong unemployment for four years. They study in a system when they are alienated and indulged in cut-throat competition against each other and where the life they live on campus is far from what they imagine. The day must come soon when the students are empowered to organise, understand, and redefine their relationship with education so that they can truly achieve the best with their potential.