W.G. Sebald opens his novel Vertigo with the story of Marie-Henri Beyle, who, in 1800, crosses the Alps with the Reserve Army of Napoleon Bonaparte. Emerging at last from the treacherous Great St. Bernard Pass, Beyle is struck by the beauty of the valley that unfolds before him: the Italian town of Ivrea can be seen in the distance; Monte Rosa dominates the skyline.

This image would impress itself powerfully on Beyle’s mind. Decades passed, and yet he could still recall every detail. In his old age, Beyle would suffer “severe disappointment” when he discovered amidst a collection of old papers an engraving entitled Prospetto d’Ivrea. This souvenir, purchased in the Italian town as the army passed through it, depicted the very scene Beyle had long understood to be the product of his own experience. The engraving’s details had displaced those gathered firsthand; the vision he had so cherished as his own turned out to be merely a memory of this souvenir.

Beyle, in this story, has quite literally been deceived by a souvenir. Sebald uses the tale to demonstrate how memory can be mediated through objects, and in some cases completely reconfigured by them. Beyle, better known under his pen name Stendhal, is direct in encouraging people not to purchase engravings of fine views, advocating instead the intensity, immediacy and necessary instability of experience. This slippery relationship between truth and memory, experience and image, provides the inspiration for Rida Fatima’s recent exhibition at the Shakir Ali Museum in Lahore. Like Sebald, Fatima is interested to explore in her art what she calls a “category of memory disorder”, specifically as it shapes engagements with the changing urban landscape of Lahore.

Fatima’s emphasis on the idea of a ‘souvenir’ is itself deceptive. Souvenirs are designed to transport you to another place, a place that still exists but which you have left behind, for one reason or another. So, even if Beyle’s memory of Ivrea in that sunlit valley was distorted through the image presented on the engraving, that valley and town remained in place; he could have returned to observe the mountain view anew.

Fatima’s ‘souvenirs’, in contrast, represent places that no longer exist, or buildings whose destruction is imminent. They evoke homes that have fallen in the way of the Orange Line Metro project, a major public transport initiative that has carved a path through the heart of the city, displacing communities and destabilising historic architecture to fulfil that desire called ‘development’. If Fatima’s art provides a memento for this process, it is a memento mori: a reminder of death, a token that emphasises the transience of things.

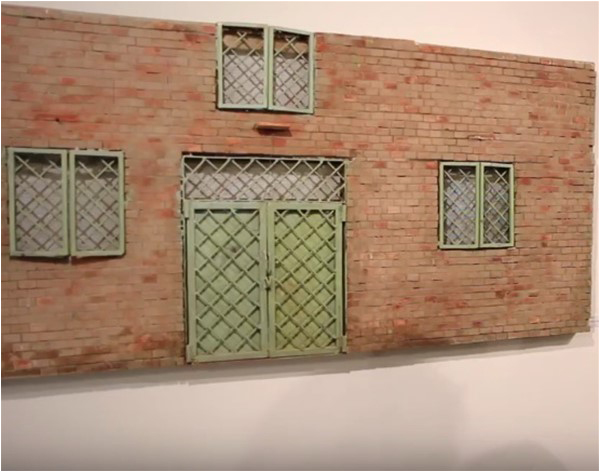

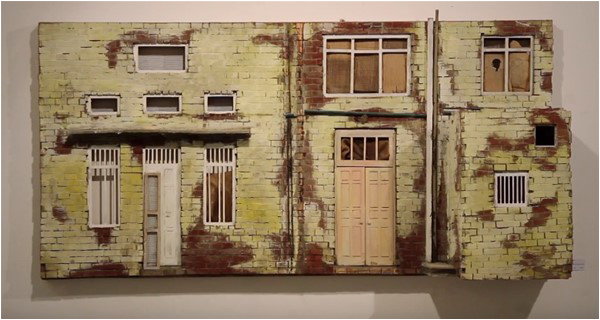

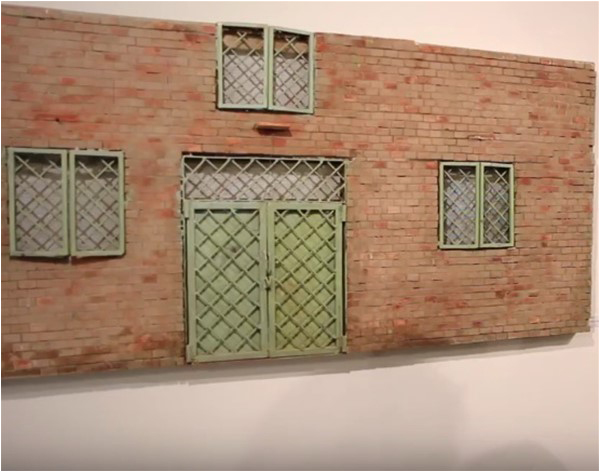

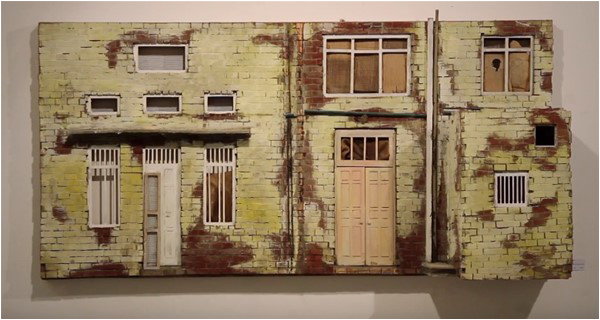

The painstaking labour that Fatima has devoted to creating her miniaturised building facades – assembling by hand every single ‘brick’ (they are in fact painted wood pieces), carefully modelling doorways and window screens, conjuring with paint the signs of dust and decay – can in this light be seen as a dedicated act of mourning.

The artist draws on her own experience navigating the city – her daily travels from Allama Iqbal Town toward Old Anarkali, to her studio space at the National College of Arts. But she is also responding to the testimonies of individuals and families directly affected by the Orange Line construction, many of whom have lost their homes or who have seen the areas in which they live changed dramatically, with no consultation and little compensation for loss. Testimonies of this sort have also been gathered by committed activists like Maryam Hussain and the #RastaBadlo movement, mobilised for court appeals and broader calls for justice; here, in Fatima’s exhibition, they are translated into miniature memorials for a struggle that continues.

It is not, however, simply the facades of ruined or threatened buildings that fill the Museum’s gallery space. On the floor near the back of the exhibition room is Fatima’s 4x8 foot model of the Great Bath of Mohenjo-daro, an important structure within the famous third millennium BC archaeological site in Sindh. Why contrast contemporary ruination in Lahore with the ancient ruins of one of the world’s oldest cities? Perhaps it is done to remind the gallery visitor that buildings can have power even after they are derelict and out of use – Mohenjo-daro is frequently invoked in Pakistan as a symbol of the innovations of Indus Valley civilisations. The Great Bath, in particular, is wielded to demonstrate the advanced public water infrastructure developed within the ancient city.

But at the same time, Fatima’s miniature Mohenjo-daro evokes the strong foundations of this structure, its grounded nature, and it rests on the floor in stark contrast to the floating facades on the wall. The Lahore buildings are portrayed without foundation, and we are thus forced to confront their transient nature – there is no weight that binds them to the ground, no guarantee that their traces will survive across generations. In this sense, they appear truly as memento mori, underlining the disposability of what they evoke, demanding recognition of the destructive processes that inspired their creation.

Chris Moffat is a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow in the School of History, Queen Mary University of London

This image would impress itself powerfully on Beyle’s mind. Decades passed, and yet he could still recall every detail. In his old age, Beyle would suffer “severe disappointment” when he discovered amidst a collection of old papers an engraving entitled Prospetto d’Ivrea. This souvenir, purchased in the Italian town as the army passed through it, depicted the very scene Beyle had long understood to be the product of his own experience. The engraving’s details had displaced those gathered firsthand; the vision he had so cherished as his own turned out to be merely a memory of this souvenir.

Beyle, in this story, has quite literally been deceived by a souvenir. Sebald uses the tale to demonstrate how memory can be mediated through objects, and in some cases completely reconfigured by them. Beyle, better known under his pen name Stendhal, is direct in encouraging people not to purchase engravings of fine views, advocating instead the intensity, immediacy and necessary instability of experience. This slippery relationship between truth and memory, experience and image, provides the inspiration for Rida Fatima’s recent exhibition at the Shakir Ali Museum in Lahore. Like Sebald, Fatima is interested to explore in her art what she calls a “category of memory disorder”, specifically as it shapes engagements with the changing urban landscape of Lahore.

Fatima’s emphasis on the idea of a ‘souvenir’ is itself deceptive. Souvenirs are designed to transport you to another place, a place that still exists but which you have left behind, for one reason or another. So, even if Beyle’s memory of Ivrea in that sunlit valley was distorted through the image presented on the engraving, that valley and town remained in place; he could have returned to observe the mountain view anew.

Fatima’s ‘souvenirs’, in contrast, represent places that no longer exist, or buildings whose destruction is imminent. They evoke homes that have fallen in the way of the Orange Line Metro project, a major public transport initiative that has carved a path through the heart of the city, displacing communities and destabilising historic architecture to fulfil that desire called ‘development’. If Fatima’s art provides a memento for this process, it is a memento mori: a reminder of death, a token that emphasises the transience of things.

The painstaking labour that Fatima has devoted to creating her miniaturised building facades – assembling by hand every single ‘brick’ (they are in fact painted wood pieces), carefully modelling doorways and window screens, conjuring with paint the signs of dust and decay – can in this light be seen as a dedicated act of mourning.

The artist draws on her own experience navigating the city – her daily travels from Allama Iqbal Town toward Old Anarkali, to her studio space at the National College of Arts. But she is also responding to the testimonies of individuals and families directly affected by the Orange Line construction, many of whom have lost their homes or who have seen the areas in which they live changed dramatically, with no consultation and little compensation for loss. Testimonies of this sort have also been gathered by committed activists like Maryam Hussain and the #RastaBadlo movement, mobilised for court appeals and broader calls for justice; here, in Fatima’s exhibition, they are translated into miniature memorials for a struggle that continues.

Why contrast contemporary ruination in Lahore with the ancient ruins of one of the world's oldest cities? Perhaps it is done to remind the gallery visitor that buildings can have power even after they are derelict and out of use

It is not, however, simply the facades of ruined or threatened buildings that fill the Museum’s gallery space. On the floor near the back of the exhibition room is Fatima’s 4x8 foot model of the Great Bath of Mohenjo-daro, an important structure within the famous third millennium BC archaeological site in Sindh. Why contrast contemporary ruination in Lahore with the ancient ruins of one of the world’s oldest cities? Perhaps it is done to remind the gallery visitor that buildings can have power even after they are derelict and out of use – Mohenjo-daro is frequently invoked in Pakistan as a symbol of the innovations of Indus Valley civilisations. The Great Bath, in particular, is wielded to demonstrate the advanced public water infrastructure developed within the ancient city.

But at the same time, Fatima’s miniature Mohenjo-daro evokes the strong foundations of this structure, its grounded nature, and it rests on the floor in stark contrast to the floating facades on the wall. The Lahore buildings are portrayed without foundation, and we are thus forced to confront their transient nature – there is no weight that binds them to the ground, no guarantee that their traces will survive across generations. In this sense, they appear truly as memento mori, underlining the disposability of what they evoke, demanding recognition of the destructive processes that inspired their creation.

Chris Moffat is a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow in the School of History, Queen Mary University of London