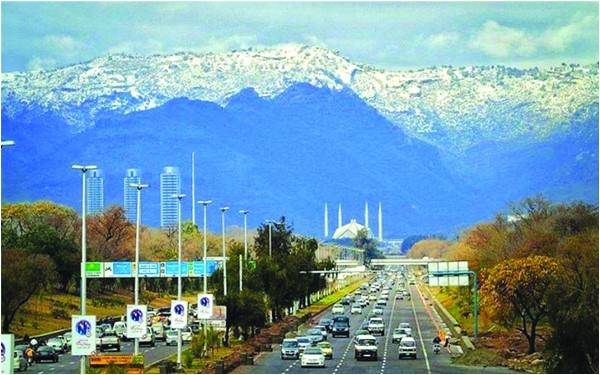

Mohsin Baig’s family moved from Jammu and settled in Rawalpindi long before Field Marshal Ayub Khan declared Islamabad the capital of Pakistan. Surrounded by the picturesque Margallah Hills, the new capital city was only a couple of hours drive from the general’s hometown in Rehana.

Islamabad was a ghost town back then, with only two major markets – Aabpara and Kohsar. Now, Aabpara is popular among the middle class and is famous for its traffic congestion and parking issues. Kohsar, with its quaint cafes and restaurants, is a hotspot for the city’s elites and the diplomats who reside here.

Baig recalls his memories with a tinge of nostalgia and, sometimes, regret. A local Pakistan People’s Party politician, Agha Riazul Islam, owed Baig’s family Rs200,000 under a property exchange agreement. In his carefree days as a youth, Baig was eager to recover the money so he could buy a new Toyota car - similar to the contemporary youth’s fascination with two-door luxury cars.

One day, Islam took Baig to Islamabad’s Club Road and showed him a piece of land. He offered to sell him the land and asked for an additional Rs100,000, since the land was worth more than Rs300,000. Baig refused and demanded cash and he finally got it only to buy his dream car the very next day. This memory is from the 1980s.

The land Baig refused to accept was adjacent to where now Best Western Hotel is situated. The investment of Rs300,000, if Mr Baig had made 30 years ago, could make him richer by Rs 1.5 billion by now.

“I did not have the vision back then. Besides, we, the people of Rawalpindi, did not like to go beyond Satellite Town (of the city). Investment in real estate in Islamabad was like investing in Gwadar these days,” Baig explains. He lived the moment and got what hardly anyone of his age had in Rawalpindi.

Waqas Shah, owner of Best Western Hotel, renovated his hotel. He made a huge investment because he knew the hotel industry was flourishing in the federal capital. “Despite all my wealth, I cannot build such a property again. I bought the land with Rs2.7 million. Now I have an offer to sell it for Rs2 billion. I would never sell this property,” he tells The Friday Times.

Not long ago, the federal capital was known as an artificial city, the city of settlers and the city with no culture. During Eid holidays, the city was nearly deserted. The city editor always had a feature ready for those specific occasions, with only a little tinkering. The property boom had yet to take people from the rags to riches.

The property boom of early 2000s transformed Islamabad forever. The sectors were developed with supersonic speed. The peripheries bustled with massive construction after people turned there to build their dream homes, due to unaffordable property prices in central areas of Islamabad.

Businesses of housing societies skyrocketed primarily because the Capital Development Authority (CDA) failed to develop any new sector for nearly three decades. The city that was once peaceful and tranquil witnessed an abnormal commercialization, population growth and traffic jams.

The CDA acquired land from locals to develop the federal capital. They were compensated with residential and commercial plots in the developed sectors. Their lives changed both financially and socially.

Areas like Bani Gala, Tarlai, Pir Sohawa, Golra, Shah Allah Ditta, Tarnol, Snagjani, Said Pur, Kirpa and Chak Shahzad became goldmines for those who had possession of land there. With the entry of public and private players in real estate sectors, including Bahria Town, Defence Housing Authority (DHA), Gulberg Greens and Top City, the transformation was taken to a whole new level.

Though small in size, the term ‘cities within in a city’ suits Islamabad. Alif Shafaq used that analogy for Istanbul, given the cultural diversity of the Turkish city. Each town and locality of Islamabad has its own strengths and weaknesses. If Bahria Town offers the best utilities and services, the advantage is offset by the distance from downtown Islamabad. The same is the case with DHA.

Almost every affluent politician owns at least one property in Islamabad. Asif Ali Zardari, Chaudhry Shujat Hussain, Raja Pervez Ashraf and Humayun Akhter have sprawling residences in F-8 sector. Imran Khan used to live in the most expensive E-7 sector before he moved to his Bani Gala residence. The Margallah Road, which goes through F and E sectors, gives a glimpse of expansive bungalows worth as much as Rs30 to Rs50 million each.

Recently, the CDA decided to allocate 1,000 acres to Pakistan Army which intends to shift its offices and residences to Islamabad from Rawalpindi. The new General Headquarters would cost the national exchequer more than Rs170 billion. Last year, Defence Secretary Lt Gen (r) Zamirul Hassan informed a Senate standing committee that the GHQ would be shifted to Islamabad against the above mentioned cost.

The shifting of the GHQ would also displace more than 7,000 families from sectors E-10, D-11 and H-16 (which are still under-developed). The locals were already asked to vacate their ancestral land against some compensation in sector H-16 that was originally meant for education institutions.

Malik Islam, a real estate businessman, who deals with property near the proposed site of the new GHQ, says the price of land has gone up. He says the peripheries were no more within the reach of middle-class people for two major reasons. First, they are not far from the city centre. Secondly, the services available are as good as any other developed sectors.

Islamabad has two big shrines – Golra and Bari Imam. Both shrines possess large area of precious land which they also use for commercial purposes. Golra State, as Pirs (saints) liked their land to be called, has best utilized its land. Not long ago, the sector E-11 and beyond, that was part of the so-called Golra State, was a dark and deserted area. More than 20 marquees and countless residential towers have appeared on the skyline over the last few years.

“I pay Rs100,000 per kanal rent to Golra State,” says Farhan, owner of a marquee. He said he got 20 kanals land from the Pirs of Golra to develop his business. According to him, the Golra State earns more than Rs40 million per month from the marquees alone in monthly rents. The CDA had objected to the commercial activities of Golra State, but the Pirs managed to sway Yousuf Raza Gilani, who was then prime minister, and who regularised their lands and authorised them to continue with commercial activities.

A CDA official says Islamabad could have been much more affordable provided the civic body did its work honestly and efficiently. He says the CDA’s inability to develop more sectors caused a massive rise in property prices. And that was a major reason why housing society and small projects in the peripheries flourished.

Several years ago, the majority people from Islamabad used to visit Rawalpindi to dine. Not anymore. Now the city offers a range of traditional, continental and exotic foods. One can have a decent meal in less than Rs150. The expensive places would make one’s wallet several thousand rupees lighter.

A new and flourishing trend in Islamabad is coffee shops representing several international and local brands. “People are conscious of status now. They would like to hang out at such places. Ironically, I can buy cheaper coffee from Starbucks than here,” says Urooj, a coffee lover, while sipping her caramel latte in a popular coffee shop at Kohsar Market.

A person visiting Islamabad after 10 or so years would not recognize the city. The greenery is decreasing thanks to mega road development and metro projects. The Margallah Hills, where no commercial activity was allowed, now have restaurants and small hotels. Everyday thousands of people visit those places, causing degradation of their natural beauty.

Lastly, one can measure the worth of Islamabad with what Malik Riaz, the owner of Bahria Town, once told a few senior CDA officials. He reportedly asked them to let him develop the land situated on each side of Islamabad Highway. In return, he promised to settle Pakistan’s entire external debt through the investment he could bring in from foreign countries.

This font was created specially for TFT's Authenti(cities) series by Habib University student Zainab Kazmi. It is called 'Fracture' and works with the original font of Didot.

Islamabad was a ghost town back then, with only two major markets – Aabpara and Kohsar. Now, Aabpara is popular among the middle class and is famous for its traffic congestion and parking issues. Kohsar, with its quaint cafes and restaurants, is a hotspot for the city’s elites and the diplomats who reside here.

Baig recalls his memories with a tinge of nostalgia and, sometimes, regret. A local Pakistan People’s Party politician, Agha Riazul Islam, owed Baig’s family Rs200,000 under a property exchange agreement. In his carefree days as a youth, Baig was eager to recover the money so he could buy a new Toyota car - similar to the contemporary youth’s fascination with two-door luxury cars.

One day, Islam took Baig to Islamabad’s Club Road and showed him a piece of land. He offered to sell him the land and asked for an additional Rs100,000, since the land was worth more than Rs300,000. Baig refused and demanded cash and he finally got it only to buy his dream car the very next day. This memory is from the 1980s.

The land Baig refused to accept was adjacent to where now Best Western Hotel is situated. The investment of Rs300,000, if Mr Baig had made 30 years ago, could make him richer by Rs 1.5 billion by now.

“I did not have the vision back then. Besides, we, the people of Rawalpindi, did not like to go beyond Satellite Town (of the city). Investment in real estate in Islamabad was like investing in Gwadar these days,” Baig explains. He lived the moment and got what hardly anyone of his age had in Rawalpindi.

Waqas Shah, owner of Best Western Hotel, renovated his hotel. He made a huge investment because he knew the hotel industry was flourishing in the federal capital. “Despite all my wealth, I cannot build such a property again. I bought the land with Rs2.7 million. Now I have an offer to sell it for Rs2 billion. I would never sell this property,” he tells The Friday Times.

Businesses of housing societies skyrocketed primarily because the Capital Development Authority failed to develop any new sector for nearly three decades

Not long ago, the federal capital was known as an artificial city, the city of settlers and the city with no culture. During Eid holidays, the city was nearly deserted. The city editor always had a feature ready for those specific occasions, with only a little tinkering. The property boom had yet to take people from the rags to riches.

The property boom of early 2000s transformed Islamabad forever. The sectors were developed with supersonic speed. The peripheries bustled with massive construction after people turned there to build their dream homes, due to unaffordable property prices in central areas of Islamabad.

Businesses of housing societies skyrocketed primarily because the Capital Development Authority (CDA) failed to develop any new sector for nearly three decades. The city that was once peaceful and tranquil witnessed an abnormal commercialization, population growth and traffic jams.

The CDA acquired land from locals to develop the federal capital. They were compensated with residential and commercial plots in the developed sectors. Their lives changed both financially and socially.

Areas like Bani Gala, Tarlai, Pir Sohawa, Golra, Shah Allah Ditta, Tarnol, Snagjani, Said Pur, Kirpa and Chak Shahzad became goldmines for those who had possession of land there. With the entry of public and private players in real estate sectors, including Bahria Town, Defence Housing Authority (DHA), Gulberg Greens and Top City, the transformation was taken to a whole new level.

Though small in size, the term ‘cities within in a city’ suits Islamabad. Alif Shafaq used that analogy for Istanbul, given the cultural diversity of the Turkish city. Each town and locality of Islamabad has its own strengths and weaknesses. If Bahria Town offers the best utilities and services, the advantage is offset by the distance from downtown Islamabad. The same is the case with DHA.

Almost every affluent politician owns at least one property in Islamabad. Asif Ali Zardari, Chaudhry Shujat Hussain, Raja Pervez Ashraf and Humayun Akhter have sprawling residences in F-8 sector. Imran Khan used to live in the most expensive E-7 sector before he moved to his Bani Gala residence. The Margallah Road, which goes through F and E sectors, gives a glimpse of expansive bungalows worth as much as Rs30 to Rs50 million each.

Recently, the CDA decided to allocate 1,000 acres to Pakistan Army which intends to shift its offices and residences to Islamabad from Rawalpindi. The new General Headquarters would cost the national exchequer more than Rs170 billion. Last year, Defence Secretary Lt Gen (r) Zamirul Hassan informed a Senate standing committee that the GHQ would be shifted to Islamabad against the above mentioned cost.

The shifting of the GHQ would also displace more than 7,000 families from sectors E-10, D-11 and H-16 (which are still under-developed). The locals were already asked to vacate their ancestral land against some compensation in sector H-16 that was originally meant for education institutions.

Malik Islam, a real estate businessman, who deals with property near the proposed site of the new GHQ, says the price of land has gone up. He says the peripheries were no more within the reach of middle-class people for two major reasons. First, they are not far from the city centre. Secondly, the services available are as good as any other developed sectors.

Islamabad has two big shrines – Golra and Bari Imam. Both shrines possess large area of precious land which they also use for commercial purposes. Golra State, as Pirs (saints) liked their land to be called, has best utilized its land. Not long ago, the sector E-11 and beyond, that was part of the so-called Golra State, was a dark and deserted area. More than 20 marquees and countless residential towers have appeared on the skyline over the last few years.

“I pay Rs100,000 per kanal rent to Golra State,” says Farhan, owner of a marquee. He said he got 20 kanals land from the Pirs of Golra to develop his business. According to him, the Golra State earns more than Rs40 million per month from the marquees alone in monthly rents. The CDA had objected to the commercial activities of Golra State, but the Pirs managed to sway Yousuf Raza Gilani, who was then prime minister, and who regularised their lands and authorised them to continue with commercial activities.

A CDA official says Islamabad could have been much more affordable provided the civic body did its work honestly and efficiently. He says the CDA’s inability to develop more sectors caused a massive rise in property prices. And that was a major reason why housing society and small projects in the peripheries flourished.

Several years ago, the majority people from Islamabad used to visit Rawalpindi to dine. Not anymore. Now the city offers a range of traditional, continental and exotic foods. One can have a decent meal in less than Rs150. The expensive places would make one’s wallet several thousand rupees lighter.

A new and flourishing trend in Islamabad is coffee shops representing several international and local brands. “People are conscious of status now. They would like to hang out at such places. Ironically, I can buy cheaper coffee from Starbucks than here,” says Urooj, a coffee lover, while sipping her caramel latte in a popular coffee shop at Kohsar Market.

A person visiting Islamabad after 10 or so years would not recognize the city. The greenery is decreasing thanks to mega road development and metro projects. The Margallah Hills, where no commercial activity was allowed, now have restaurants and small hotels. Everyday thousands of people visit those places, causing degradation of their natural beauty.

Lastly, one can measure the worth of Islamabad with what Malik Riaz, the owner of Bahria Town, once told a few senior CDA officials. He reportedly asked them to let him develop the land situated on each side of Islamabad Highway. In return, he promised to settle Pakistan’s entire external debt through the investment he could bring in from foreign countries.

This font was created specially for TFT's Authenti(cities) series by Habib University student Zainab Kazmi. It is called 'Fracture' and works with the original font of Didot.