Once upon a time, there lived an Emperor who was entirely obsessed with the idea of wearing the most extraordinary garments. He had heard tales of fabrics so delicate and light that they were entirely invisible to the naked eye. Two cunning swindlers arrived at his court, claiming to be able to craft for him such an outfit from pure magic, that it would appear as though he wore nothing at all! Of course, the emperor believed every word and agreed immediately.

The emperor wanted to find out who in his empire is stupid and foolish, unworthy of the position he is holding. The emperor, not wanting to admit his own lack of judgement, wears the "invisible" clothes and parades in front of his people, when no one in the entire city except a child proclaimed the truth “the Emperor is without clothes.”

It is indeed a fascinating phenomenon that this story from our kindergarten days is so widely known and yet, so few truly understand it. Even today, the story remains incredibly relevant and has a powerful message that holds true in the present day. In fact, it is quite remarkable that a story written so long ago can still have such a profound impact on our lives. This is the story of vanity and insecurity at the same time, where all, including the most learned, in order to save their portfolios and status in society doubted their life-long learning, common sense and wisdom to succumb to the cunning of two swindlers.

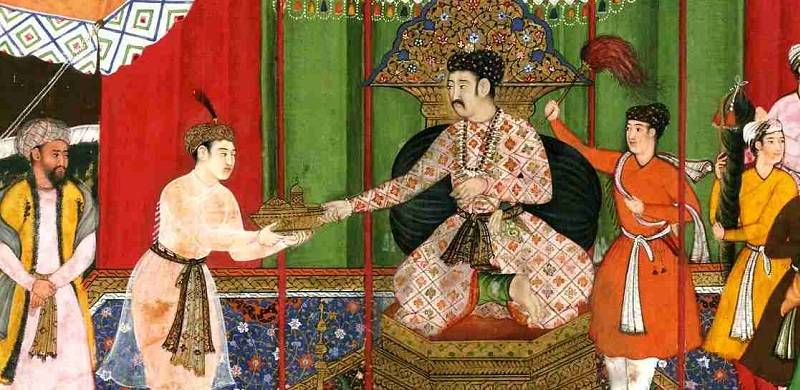

Darbari attitudes are neither a recent phenomenon nor exclusive to Pakistan. However, in Pakistan, they have become entrenched into the country's culture.

Darbari culture is as old as the history of humankind. Socrates saw flattery as a form of deception that was incompatible with the virtues of honesty, justice, and genuine friendship. In Plato’s book “The Republic,” Socrates believed that flattery was a form of false praise that could lead people to become vain and arrogant, making them susceptible to manipulation and corruption. Plato, like his mentor, criticizes flattery as a “fake” that can lead individuals and societies astray from the pursuit of truth and virtue. While other ills and vices corrupts oneself, Darbari attitude corrupts the others that are being flattered into a self-delusional syndrome. Danial Kaput, in his book “Flattery and the History of Political Thought” explains the phenomenon of Darbari attitudes to be an outcome of asymmetric power structures in societies where the weak are coerced by the powerful, and flattery is a tool of the weak; it is a way of trying to gain influence over the powerful without having the strength or authority to do so overtly, in other words a deceptive and convincing performance for an agenda.

Darbariat is a devious thing that often comes with mutual benefits. It involves one person giving praise to another in the hopes of receiving a response in kind. While this exchange of compliments can be beneficial in the short term, it can also be damaging and lead to a dangerous cycle of self-glorification and insecurity. It invokes a false sense of accomplishment. Darbari traits are an art and science at the same time, where these can be expressed through more than just words, as these can be demonstrated through one's body language and physical demeanor. A single gaze of admiration, a glowing grin, an approving tilt of the head, or even a posture of captivating attention may all contribute to achieving the desired impact. A darbari would deftly weave a web of secrecy and solitude around the target, effectively cutting them off from the rest of the eager world.

Voula Tsouna's work on the “Ethics of Philodemus” reveals a powerful connection between incompetence, vanity, and insecurity. The incompetent boss hangs onto every word of flattery, revealing in its bolstering effect on his ego and self-esteem. On the contrary, a well rounded individual, aware of her strengths and weaknesses, would not be swayed by such unbecoming gestures. Instead, they would feel a sense of unease and discomfort with flattery. The other part of the equation is the insecurity, which is related to the subordinates or those who master the art and science of flattery. Why do they have to rely on this trait?

Apparently, a simple question on the face of it but it has deep psychological complexities. From social disorder to individual psychology, from peer pressure to fear of losing status, from incompetence to compete with the competent, in "Civilization and its Discontents," Sigmund Freud examines the idea that the conflicts between individual desires and the demands of society can lead to insecurity and frustration. In a nutshell, all these insecurities discourage most to compete, and encourage them to rather adopt a shortcut in the shape of darbari attitude - an easy way out to remain relevant and survive.

Ancient Greek philosophers have talked much about such vices, and this has been a subject of debate for a long-time in the history of humankind. So why a write up on this beaten issue? Throughout history, flattery has been seen as a vice, and many nations have denounced it in favor of competence.

Developed nations have taken a collective stand against this menace, as they realized that against short-term advantages and gains, it is not a viable long-term strategy when it comes to human resource development and progress of society. Instead, they emphasize the importance of building a culture of competence and meritocracy.

It is, however, heart-breaking to witness darbari culture having seeped into our society, transforming the basic fabric of our culture altogether. This menace has taken hold not only in state institutions like the bureaucracy and various government departments, but has brought about a genuine cultural transformation of society.

We generally point fingers towards the government officials and staff for darbari trends but if we objectively peep into society, we will find a horrifying reality. Each one of us, for varying reasons now, not only suffers from this syndrome but are also advocating it to our younger generation, including our own children. Who cares for competence when the ladder of success, relevance and survival can be climbed through being a darbari, a flatterer and a yes man. There is a complete cycle, where the incompetent when they attain the position that matters, embrace sycophancy naturally.

Talented and hardworking professionals in Pakistan are often left disheartened and discouraged, due to the lack of recognition for their efforts. Unqualified and incompetent individuals are given preference over them for promotions and benefits. On an almost daily basis, we witness incompetent darbaris refuting good ideas, plans and strategies by the competent, just by getting the air of the likely attitude or tilt of the boss towards an idea without much critical thought and deliberations.

Academia is a witness to the phenomenon of students literally begging for marks in examinations, making one excuse or the other, and faculty accepting these transgressions for cheap popularity. The same attitude is seen in our homes, where parents teach their children to not confront their boss with reality and truth for fear of losing their job or position. This is a systemic problem, where the culture of not speaking the truth or challenging authority has been perpetuated.

The dilemma of professionals and competent people who are truly concerned about the wellbeing of an outfit are constrained to highlight the pitfalls of an idea or a decision of the authorities due to fear of retribution. Fears may arise from a variety of reasons, such as job insecurity. Whistleblowing, once a quality that was seen as admirable and even heroic, is now viewed as a dangerous and even detrimental trait to possess. This is especially true in government offices, state institutions and the corporate world, where a whistleblower’s actions can be met with swift and severe repercussions from their bosses and employer.

To combat this culture a top-down approach is the way forward, where open communication is the key to success. Creating an environment that values transparency, honesty, and open communication is essential for society to make progress and help its citizens to respect professionalism and competence. This type of open dialogue can help to foster a culture of innovation and creativity, as well as build a sense of community among citizens, which values the collective good instead of individualism. In an environment where people feel safe and secure, they are more likely to contribute their ideas, take risks, and be more productive. This can lead to more meaningful relationships among citizens, as well as increased trust in their government and other institutions.

The Athenians work on parrhesia, which meant "frank speech" is the way forward. Philodemus, in "On Frank Speech," emphasized the importance of speaking openly and honestly without fear of being punished or facing consequences. He also noted that frank speech helps to prevent wrongdoing. At the same time, he highlighted the pitfalls and dangers inherent in frank speech for both categories, those who are incompetent and indulge in frank speech based on emotions only and those who are highly competent but indulge with arrogance. So, the take-home from Philodemus’s “On Frank Speech” is the art of communication. Since inception, we, in our individual capacities and as a society, have been scolded and frowned upon for frank speech, in our homes, in our schools, at our workplace, whether private or public offices. Therefore, we as individuals or as a society are unaware and not trained in the art of communication - a culpability for which our people and society should not be blamed.

In our context therefore, frank speech is the key to progression and development as a society. Since this is a top-down approach, therefore, it is important for leaders at all levels to create an environment where employees feel comfortable sharing their perspectives and raising concerns without fear of reprisal. There is no denying the fact that breaking away from a darbari culture, where flattery and sycophancy are valued over honesty and competence, can be a gigantic challenge since society cannot be changed with a flick or press of a remote-control button. However, by promoting a culture of openness and encouraging feedback in homes, organizations, and offices, we can help to create a more productive and effective work environment.

The first and foremost step is effecting genuine change in the education system of Pakistan. The closed book examination regime that encourages rote learning, parroting and copy-paste culture needs structural rethinking. An education system where knowledge should be a function of understanding and not memory, I believe is the way forward, where questioning and metacognition is encouraged by all.

Let them speak - correct them, teach them the art of speech, but don’t mute them. If they will not speak - how will they learn?

The emperor wanted to find out who in his empire is stupid and foolish, unworthy of the position he is holding. The emperor, not wanting to admit his own lack of judgement, wears the "invisible" clothes and parades in front of his people, when no one in the entire city except a child proclaimed the truth “the Emperor is without clothes.”

Darbari attitudes are neither a recent phenomenon nor exclusive to Pakistan. However, in Pakistan, they have become entrenched into the country's culture.

It is indeed a fascinating phenomenon that this story from our kindergarten days is so widely known and yet, so few truly understand it. Even today, the story remains incredibly relevant and has a powerful message that holds true in the present day. In fact, it is quite remarkable that a story written so long ago can still have such a profound impact on our lives. This is the story of vanity and insecurity at the same time, where all, including the most learned, in order to save their portfolios and status in society doubted their life-long learning, common sense and wisdom to succumb to the cunning of two swindlers.

Darbari attitudes are neither a recent phenomenon nor exclusive to Pakistan. However, in Pakistan, they have become entrenched into the country's culture.

Darbari culture is as old as the history of humankind. Socrates saw flattery as a form of deception that was incompatible with the virtues of honesty, justice, and genuine friendship. In Plato’s book “The Republic,” Socrates believed that flattery was a form of false praise that could lead people to become vain and arrogant, making them susceptible to manipulation and corruption. Plato, like his mentor, criticizes flattery as a “fake” that can lead individuals and societies astray from the pursuit of truth and virtue. While other ills and vices corrupts oneself, Darbari attitude corrupts the others that are being flattered into a self-delusional syndrome. Danial Kaput, in his book “Flattery and the History of Political Thought” explains the phenomenon of Darbari attitudes to be an outcome of asymmetric power structures in societies where the weak are coerced by the powerful, and flattery is a tool of the weak; it is a way of trying to gain influence over the powerful without having the strength or authority to do so overtly, in other words a deceptive and convincing performance for an agenda.

Darbariat is a devious thing that often comes with mutual benefits. It involves one person giving praise to another in the hopes of receiving a response in kind. While this exchange of compliments can be beneficial in the short term, it can also be damaging and lead to a dangerous cycle of self-glorification and insecurity. It invokes a false sense of accomplishment. Darbari traits are an art and science at the same time, where these can be expressed through more than just words, as these can be demonstrated through one's body language and physical demeanor. A single gaze of admiration, a glowing grin, an approving tilt of the head, or even a posture of captivating attention may all contribute to achieving the desired impact. A darbari would deftly weave a web of secrecy and solitude around the target, effectively cutting them off from the rest of the eager world.

Voula Tsouna's work on the “Ethics of Philodemus” reveals a powerful connection between incompetence, vanity, and insecurity. The incompetent boss hangs onto every word of flattery, revealing in its bolstering effect on his ego and self-esteem. On the contrary, a well rounded individual, aware of her strengths and weaknesses, would not be swayed by such unbecoming gestures. Instead, they would feel a sense of unease and discomfort with flattery. The other part of the equation is the insecurity, which is related to the subordinates or those who master the art and science of flattery. Why do they have to rely on this trait?

Apparently, a simple question on the face of it but it has deep psychological complexities. From social disorder to individual psychology, from peer pressure to fear of losing status, from incompetence to compete with the competent, in "Civilization and its Discontents," Sigmund Freud examines the idea that the conflicts between individual desires and the demands of society can lead to insecurity and frustration. In a nutshell, all these insecurities discourage most to compete, and encourage them to rather adopt a shortcut in the shape of darbari attitude - an easy way out to remain relevant and survive.

Ancient Greek philosophers have talked much about such vices, and this has been a subject of debate for a long-time in the history of humankind. So why a write up on this beaten issue? Throughout history, flattery has been seen as a vice, and many nations have denounced it in favor of competence.

Developed nations have taken a collective stand against this menace, as they realized that against short-term advantages and gains, it is not a viable long-term strategy when it comes to human resource development and progress of society. Instead, they emphasize the importance of building a culture of competence and meritocracy.

It is, however, heart-breaking to witness darbari culture having seeped into our society, transforming the basic fabric of our culture altogether. This menace has taken hold not only in state institutions like the bureaucracy and various government departments, but has brought about a genuine cultural transformation of society.

We generally point fingers towards the government officials and staff for darbari trends but if we objectively peep into society, we will find a horrifying reality. Each one of us, for varying reasons now, not only suffers from this syndrome but are also advocating it to our younger generation, including our own children. Who cares for competence when the ladder of success, relevance and survival can be climbed through being a darbari, a flatterer and a yes man. There is a complete cycle, where the incompetent when they attain the position that matters, embrace sycophancy naturally.

Talented and hardworking professionals in Pakistan are often left disheartened and discouraged, due to the lack of recognition for their efforts. Unqualified and incompetent individuals are given preference over them for promotions and benefits. On an almost daily basis, we witness incompetent darbaris refuting good ideas, plans and strategies by the competent, just by getting the air of the likely attitude or tilt of the boss towards an idea without much critical thought and deliberations.

Academia is a witness to the phenomenon of students literally begging for marks in examinations, making one excuse or the other, and faculty accepting these transgressions for cheap popularity. The same attitude is seen in our homes, where parents teach their children to not confront their boss with reality and truth for fear of losing their job or position. This is a systemic problem, where the culture of not speaking the truth or challenging authority has been perpetuated.

The dilemma of professionals and competent people who are truly concerned about the wellbeing of an outfit are constrained to highlight the pitfalls of an idea or a decision of the authorities due to fear of retribution. Fears may arise from a variety of reasons, such as job insecurity. Whistleblowing, once a quality that was seen as admirable and even heroic, is now viewed as a dangerous and even detrimental trait to possess. This is especially true in government offices, state institutions and the corporate world, where a whistleblower’s actions can be met with swift and severe repercussions from their bosses and employer.

By promoting a culture of openness and encouraging feedback in homes, organizations, and offices, we can help to create a more productive and effective work environment.

To combat this culture a top-down approach is the way forward, where open communication is the key to success. Creating an environment that values transparency, honesty, and open communication is essential for society to make progress and help its citizens to respect professionalism and competence. This type of open dialogue can help to foster a culture of innovation and creativity, as well as build a sense of community among citizens, which values the collective good instead of individualism. In an environment where people feel safe and secure, they are more likely to contribute their ideas, take risks, and be more productive. This can lead to more meaningful relationships among citizens, as well as increased trust in their government and other institutions.

The Athenians work on parrhesia, which meant "frank speech" is the way forward. Philodemus, in "On Frank Speech," emphasized the importance of speaking openly and honestly without fear of being punished or facing consequences. He also noted that frank speech helps to prevent wrongdoing. At the same time, he highlighted the pitfalls and dangers inherent in frank speech for both categories, those who are incompetent and indulge in frank speech based on emotions only and those who are highly competent but indulge with arrogance. So, the take-home from Philodemus’s “On Frank Speech” is the art of communication. Since inception, we, in our individual capacities and as a society, have been scolded and frowned upon for frank speech, in our homes, in our schools, at our workplace, whether private or public offices. Therefore, we as individuals or as a society are unaware and not trained in the art of communication - a culpability for which our people and society should not be blamed.

In our context therefore, frank speech is the key to progression and development as a society. Since this is a top-down approach, therefore, it is important for leaders at all levels to create an environment where employees feel comfortable sharing their perspectives and raising concerns without fear of reprisal. There is no denying the fact that breaking away from a darbari culture, where flattery and sycophancy are valued over honesty and competence, can be a gigantic challenge since society cannot be changed with a flick or press of a remote-control button. However, by promoting a culture of openness and encouraging feedback in homes, organizations, and offices, we can help to create a more productive and effective work environment.

The first and foremost step is effecting genuine change in the education system of Pakistan. The closed book examination regime that encourages rote learning, parroting and copy-paste culture needs structural rethinking. An education system where knowledge should be a function of understanding and not memory, I believe is the way forward, where questioning and metacognition is encouraged by all.

Let them speak - correct them, teach them the art of speech, but don’t mute them. If they will not speak - how will they learn?