The short-stories of Masroor Jahan with their absent and present realities are milestones of her creative journey which will not be easily forgotten. About her own stories, she used to say:

“Actually life is not unidirectional. It has a thousand aspects and every aspect is a complete world in itself. The fiction writer is a pulse-reader of life. It is their duty to present every aspect of life in its proper context.”

Masroor Jahan did not get the recognition which she rightly deserved during her life due to her distance from critics and non-participation in literary groupings. Despite that, many of her short-stories were published in Punjabi, Tamil, Telugu, English, Kashmiri, Kannada, Malayali and Braille.

Nighat Sultana Abidi attained the degree of D. Litt by writing her thesis on “Masroor Jahan: Art and Personality”. Javed Kholov of Tajikistan University has done a PhD on this thesis in Tajik. It was later translated into Russian, thus making her only the second short-story writer after her living contemporary Jilani Bano to be so honoured. Other researchers of the short story also made Masroor Jahan and her stories the topic of their theses.

Apart from short-stories, she penned 65 novels, among which the social realist Nai Basti (New Colony) is of special interest. This novel, published in 1982, was topically different from all her novels, since its atmosphere and characters were drawn from settlements which were normally ignored by people. To my knowledge, this is the first Urdu novel as per its subject where the problems of the nameless city settlements – which are called illegal – have been narrated. As to why these settlements become inhabited and what is the life and reality of their residents – these issues have been expressed well in this novel. Munshi Premchand had made the rural have-nots a subject of his novels, but in Masoor Jahan’s work are those urban have-nots, who have their own problems. She depicts them living a life and values that are being trampled on.

In this era of industrial production and consumerism when the short-story has become attentive towards topics like loneliness, helplessness, the meaninglessness of life, terrorism, war and modernity, a lot of changes have also occurred in the experience of women. With the external experiences, their inner feelings have also changed. The image of the domestic courtyard, for instance, is not the same as that of old. Such themes are covered in Masroor Jahan’s stories. But basically she was the supporter of an enlightened society where along with equality for women, such attitudes were also necessary which give them such authority that they do not feel crippled. After a mortal blow to the old image of a patriarchal system and family, and notwithstanding the speed at which society is changing its garb, despite all her freedoms, the woman in it is still far from equality. Masroor Jahan not only observed her surroundings but after discovering the realities of her time presented a sketch of the life of Muslim homes, much of which is affected by anxieties around the social position of a woman.

The greatest quality of Masroor Jahan’s short stories was that they, in addition to manifesting the changes in human society and human relations, talk about the woman and family whose construction or destruction is itself a topic. These stories written in easily comprehensible and beautiful prose were actually the stories of a search for life, where every character has their own respective paths and milestones. How successful or unsuccessful these stories were in the search for these paths and “milestones” can only be decided by the reader of these stories. All I know is that the singularity of effect expressed in these stories always catches the reader’s attention. What more would a fiction-writer have asked for?

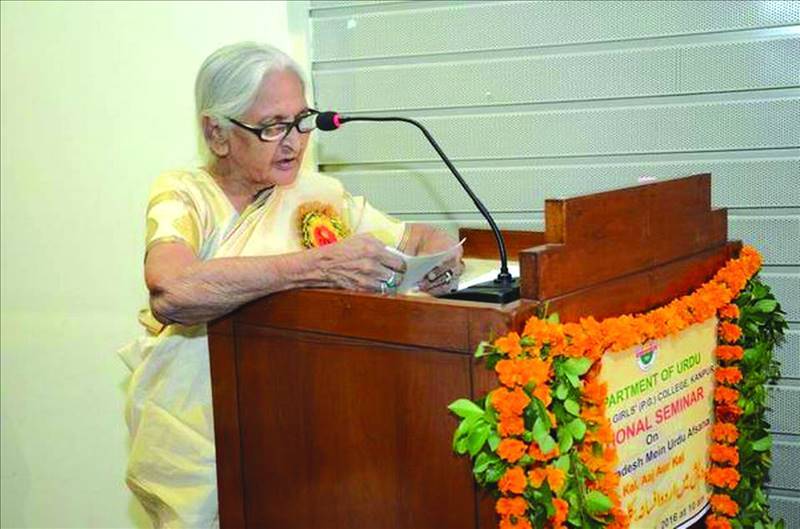

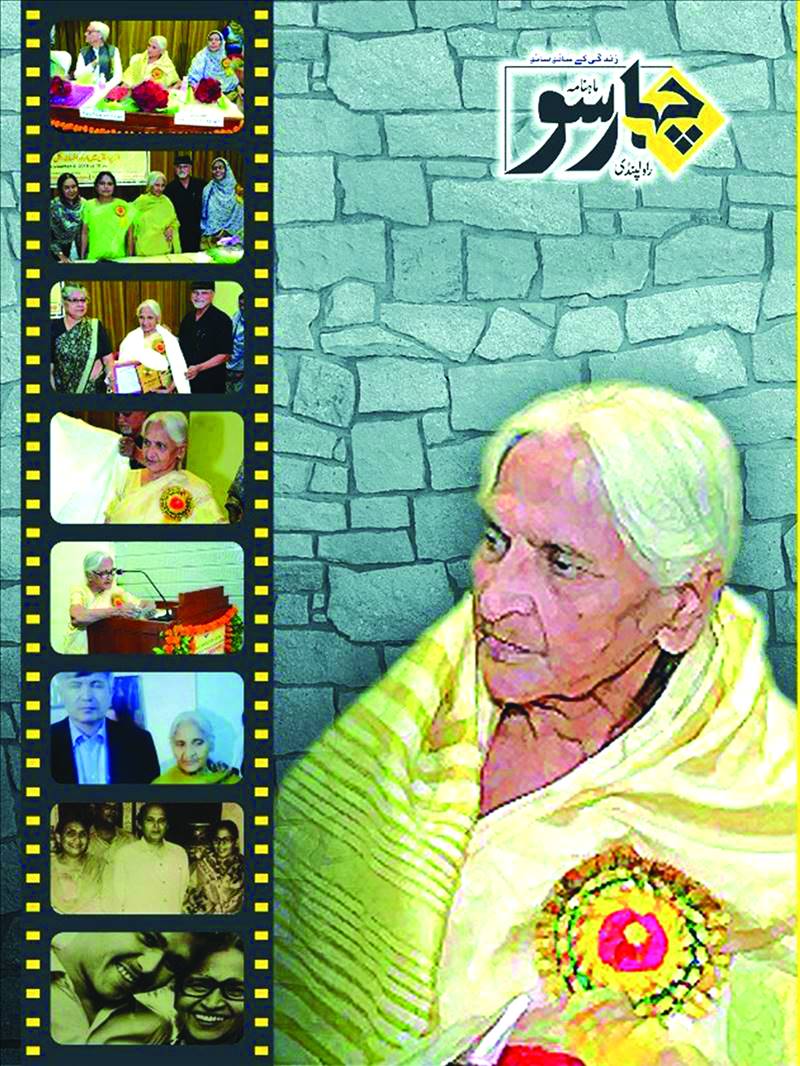

I got acquainted with Masroor Jahan barely more than a month ago when I read Shafey Kidwai’s lucid review of her two recent collections of short-stories namely Naql-e- Makaani (Migration) and Khuvaab der Khuvaab Safar (A Journey Dream After Dream) in the Friday Review of The Hindu. From there, I sought out the January/February issue of the monthly Chahaar-Su, issued from Rawalpindi, which was dedicated to Masroor Jahan and consists of an excellent and quite revealing interview of the writer with the editor Gulzar Javed. These readings also sent me down memory lane to my maiden visit to Lucknow back in 2014 when I was invited as the first ever delegate from Pakistan to the Lucknow Literature Festival. Our generous hosts took us around a heartening tour of the city, where one got a first-hand sampling of the city’s unique culinary specialties, like Tunde ke Kabab and Galawat Kabab. We were also taken to the tombs of Lucknow’s high and mighty poets and singers like Mushafi, Anees, Nasikh, Mir, Majaz and Begum Akhtar, and the old monuments of past grandees of that city. It was there, too, that I made the acquaintance of the charming and erudite Saira Mujtaba. Sadly, I do not recall any conversations we might have had with regard to her late grandmother, Masroor Jahan. Now when I think about that visit, I am disconsolate because I know I should have been spending time with the living monuments of Lucknow like Begum Masroor Jahan and Naiyer Masud, rather than the dead buildings of that city. That regret will always be mine!

Masroor Jahan’s quintessential short-story The Aged Eucalyptus talks about the eponymous tree which is a witness to the eras, revolutions, stories and secrets of the haveli where it had stood so proudly for decades in addition to being the recipient of the imprinted affections of the doomed love affair of the two main protagonists, Maliha and Ahmer. Later on, the aged eucalyptus would provide solace to Maliha as she held it to console herself in her lover’s absence. The story ends with the uprooting of the aged eucalyptus in a storm overnight. I would like to think that the aged, kind, empathetic eucalyptus was not only a metaphor for the doomed love affair in the story itself but for Masroor Jahan’s own life, patiently accumulating the various sorrows of her life, in which she had to contend with the early deaths of her brother and her son, as well as another brother who went missing in 1973 but never returned (her 1980 novel Shahvar is dedicated to him), and which she never spoke of.

The aged eucalyptus for me also reflects not the physical passing on of Masroor Jahan, but the uprooting of a whole way of life and a system of thinking and feeling which was Lakhnavi culture. It is now up to her younger successors like Anees Ashfaq and indeed my friend Saira Mujtaba (to whom Masroor Jahan’s last volume of stories Khuvaab Dar Khuvaab Safar is co-dedicated and who is currently translating a collection of her grandmother’s short stories into English) to pen the dirge of Lucknow in our own time.

Note: All translations from the Urdu are by the writer.

Raza Naeem is a social scientist and an award-winning translator currently based in Lahore. He has been trained in Political Economy from the University of Leeds in the UK and in Middle Eastern History and Anthropology from the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, USA. He is also the President of the Progressive Writers Association (PWA) in Lahore. He may be reached at: razanaeem@hotmail.com

“Actually life is not unidirectional. It has a thousand aspects and every aspect is a complete world in itself. The fiction writer is a pulse-reader of life. It is their duty to present every aspect of life in its proper context.”

Masroor Jahan did not get the recognition which she rightly deserved during her life due to her distance from critics and non-participation in literary groupings. Despite that, many of her short-stories were published in Punjabi, Tamil, Telugu, English, Kashmiri, Kannada, Malayali and Braille.

Nighat Sultana Abidi attained the degree of D. Litt by writing her thesis on “Masroor Jahan: Art and Personality”. Javed Kholov of Tajikistan University has done a PhD on this thesis in Tajik. It was later translated into Russian, thus making her only the second short-story writer after her living contemporary Jilani Bano to be so honoured. Other researchers of the short story also made Masroor Jahan and her stories the topic of their theses.

Apart from short-stories, she penned 65 novels, among which the social realist Nai Basti (New Colony) is of special interest. This novel, published in 1982, was topically different from all her novels, since its atmosphere and characters were drawn from settlements which were normally ignored by people. To my knowledge, this is the first Urdu novel as per its subject where the problems of the nameless city settlements – which are called illegal – have been narrated. As to why these settlements become inhabited and what is the life and reality of their residents – these issues have been expressed well in this novel. Munshi Premchand had made the rural have-nots a subject of his novels, but in Masoor Jahan’s work are those urban have-nots, who have their own problems. She depicts them living a life and values that are being trampled on.

In this era of industrial production and consumerism when the short-story has become attentive towards topics like loneliness, helplessness, the meaninglessness of life, terrorism, war and modernity, a lot of changes have also occurred in the experience of women. With the external experiences, their inner feelings have also changed. The image of the domestic courtyard, for instance, is not the same as that of old. Such themes are covered in Masroor Jahan’s stories. But basically she was the supporter of an enlightened society where along with equality for women, such attitudes were also necessary which give them such authority that they do not feel crippled. After a mortal blow to the old image of a patriarchal system and family, and notwithstanding the speed at which society is changing its garb, despite all her freedoms, the woman in it is still far from equality. Masroor Jahan not only observed her surroundings but after discovering the realities of her time presented a sketch of the life of Muslim homes, much of which is affected by anxieties around the social position of a woman.

The greatest quality of Masroor Jahan’s short stories was that they, in addition to manifesting the changes in human society and human relations, talk about the woman and family whose construction or destruction is itself a topic. These stories written in easily comprehensible and beautiful prose were actually the stories of a search for life, where every character has their own respective paths and milestones. How successful or unsuccessful these stories were in the search for these paths and “milestones” can only be decided by the reader of these stories. All I know is that the singularity of effect expressed in these stories always catches the reader’s attention. What more would a fiction-writer have asked for?

I got acquainted with Masroor Jahan barely more than a month ago when I read Shafey Kidwai’s lucid review of her two recent collections of short-stories namely Naql-e- Makaani (Migration) and Khuvaab der Khuvaab Safar (A Journey Dream After Dream) in the Friday Review of The Hindu. From there, I sought out the January/February issue of the monthly Chahaar-Su, issued from Rawalpindi, which was dedicated to Masroor Jahan and consists of an excellent and quite revealing interview of the writer with the editor Gulzar Javed. These readings also sent me down memory lane to my maiden visit to Lucknow back in 2014 when I was invited as the first ever delegate from Pakistan to the Lucknow Literature Festival. Our generous hosts took us around a heartening tour of the city, where one got a first-hand sampling of the city’s unique culinary specialties, like Tunde ke Kabab and Galawat Kabab. We were also taken to the tombs of Lucknow’s high and mighty poets and singers like Mushafi, Anees, Nasikh, Mir, Majaz and Begum Akhtar, and the old monuments of past grandees of that city. It was there, too, that I made the acquaintance of the charming and erudite Saira Mujtaba. Sadly, I do not recall any conversations we might have had with regard to her late grandmother, Masroor Jahan. Now when I think about that visit, I am disconsolate because I know I should have been spending time with the living monuments of Lucknow like Begum Masroor Jahan and Naiyer Masud, rather than the dead buildings of that city. That regret will always be mine!

I would like to think that the aged, kind, empathetic eucalyptus was not only a metaphor for the doomed love affair in the story itself but for Masroor Jahan’s own life, patiently accumulating the various sorrows of her life

Masroor Jahan’s quintessential short-story The Aged Eucalyptus talks about the eponymous tree which is a witness to the eras, revolutions, stories and secrets of the haveli where it had stood so proudly for decades in addition to being the recipient of the imprinted affections of the doomed love affair of the two main protagonists, Maliha and Ahmer. Later on, the aged eucalyptus would provide solace to Maliha as she held it to console herself in her lover’s absence. The story ends with the uprooting of the aged eucalyptus in a storm overnight. I would like to think that the aged, kind, empathetic eucalyptus was not only a metaphor for the doomed love affair in the story itself but for Masroor Jahan’s own life, patiently accumulating the various sorrows of her life, in which she had to contend with the early deaths of her brother and her son, as well as another brother who went missing in 1973 but never returned (her 1980 novel Shahvar is dedicated to him), and which she never spoke of.

The aged eucalyptus for me also reflects not the physical passing on of Masroor Jahan, but the uprooting of a whole way of life and a system of thinking and feeling which was Lakhnavi culture. It is now up to her younger successors like Anees Ashfaq and indeed my friend Saira Mujtaba (to whom Masroor Jahan’s last volume of stories Khuvaab Dar Khuvaab Safar is co-dedicated and who is currently translating a collection of her grandmother’s short stories into English) to pen the dirge of Lucknow in our own time.

Note: All translations from the Urdu are by the writer.

Raza Naeem is a social scientist and an award-winning translator currently based in Lahore. He has been trained in Political Economy from the University of Leeds in the UK and in Middle Eastern History and Anthropology from the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, USA. He is also the President of the Progressive Writers Association (PWA) in Lahore. He may be reached at: razanaeem@hotmail.com