Speaking to students in this country is always a bittersweet experience. One feels their spirit and determination, and a glimmer of hope for the future of Pakistan unearths itself. However, the saddening realities of the higher education crisis unfold in the depths of the conversation. Countless tales of students being denied financial aid due to budget cuts, a constant curtailment of fundamental rights across campuses, and, in the latest series of harrowing events, gross negligence that endangers the life and safety of students. As most universities shift toward operating like corporations, there are various barriers to intellectual experiences that are the essence of a university experience.

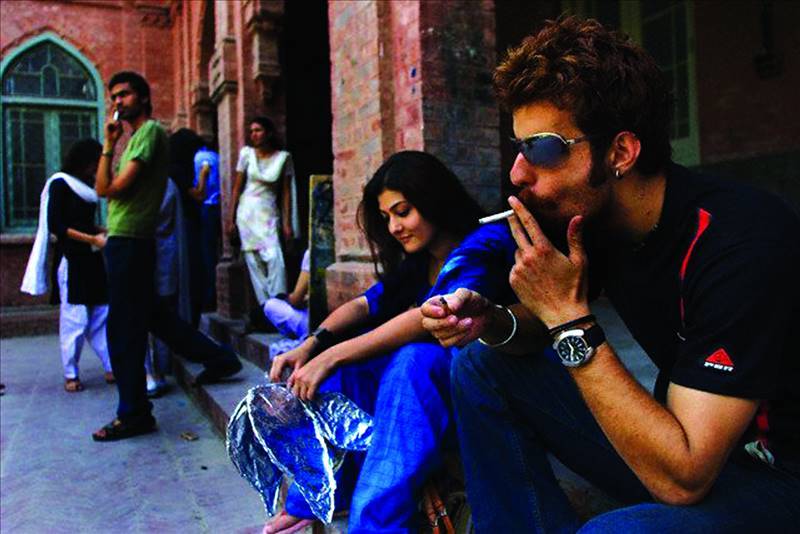

Most concerning has been the resurgence of overly paternalistic administrations who have developed an obsession with ‘correcting’ the moral fabric of their student bodies. In the last few weeks alone, various campuses across the country have revealed their fixation for female dress codes and others have announced tight checks on male female interaction as well as gross intrusions into student’s online privacy.

The problem, per se, is not the idea of universities wanting to influence the morals of their students, rather, it is the definition of morality itself, which has plagued our society, and now is doing the same to our education system. From dress codes, restricted syllabi and limitations on mobility, freedom, both intellectual and physical, has always been seen as the enemy of morality. However, there are much bigger enemies of our students’ collective moral fabric in Pakistani universities, than the non-existence of dupattas and chadars.

An average Pakistani university student goes through those four years witnessing gross ethical violations on campus ranging from blatant gender disparity and everyday harassment of female students, to severely underpaid and ill-treated janitorial and custodial staff. Additionally, our youth observe and internalise the visible discrimination minority students face, and the growing atmosphere of intolerance and aversion to debate, dialogue and open thinking. Yet, none of these issues appear on the list of ‘moral correction’ we’d like to subject our campuses to.

It is shocking that one of Pakistan’s top universities just recently hosted its first ever cultural night with music and dance, as a four-decade-old dictatorship of fundamentalist student groups is waning. Are the students who will now watch music and dance on PU’s campus more likely to be morally corrupt, or were those who were socialised during the 40 years of religious intolerance and violent mafias? Similarly, are the students who witness the slave-like conditions in which campus support staff reside not likely to reciprocate those attitudes in their homes and workplaces?

The question is larger than whether our university campuses should espouse Islamic values or uphold cultural ideals. The real question is why our cultural or religious identity feels more threatened by music, dance, liberal dresses, or male-female interaction on campuses, than it does by the complete denial of a fair and just education system. Is it not worse for the ethical values of our youth to witness violent stabbings of teachers, or the shameful treatment of ethnic minority and working class students? But the administrations and their keyboard warriors, who rejoice at the decision to make girls wear burqas in schools and universities, hardly ever use the same energy to raise their voices against harassment on campus, or unfair fee hikes, or the treatment of minority students. Pakistan is a case study in misplaced priorities where we fear open-minded thinking much more than we fear intolerance justified on the basis of religion, ethnicity, class and gender. By reciprocating the same attitudes within our student body, we are producing yet another generation of Pakistanis who can standby as a mob lynches the life out of a student accused of blasphemy.

A fundamental way in which universities differ from schools across the world is in the provision of the freedom of thought, mobility and action. This should be supplemented with a moral education that sees freedom not as an enemy, but as a means of motivating our youth to be able to have more avenues and choices and to advocate more vehemently for new ideas. It would do us justice to focus on providing a moral education to our students that prioritizes equality, tolerance, and social responsibility. This moral education should build a sense of empathy in our students for those who are from a different walk of life, and tolerance for those who might have fundamentally different points of view. Rather than caging students of different genders, it must build bridges between male and female students. It is time to shift our priorities from the lengths of a kameez, to a deeper understanding of gender equality and harassment, from the ban on cultural and musical festivities, to a metamorphosis of different cultures and ethnicities on campus and from the limitations on freedom of speech, to equipping them with the courage to raise their voices.

The writer is an entrepreneur and a women’s rights advocate. She can be reached on Twitter @nayabGJan

Most concerning has been the resurgence of overly paternalistic administrations who have developed an obsession with ‘correcting’ the moral fabric of their student bodies. In the last few weeks alone, various campuses across the country have revealed their fixation for female dress codes and others have announced tight checks on male female interaction as well as gross intrusions into student’s online privacy.

The problem, per se, is not the idea of universities wanting to influence the morals of their students, rather, it is the definition of morality itself, which has plagued our society, and now is doing the same to our education system. From dress codes, restricted syllabi and limitations on mobility, freedom, both intellectual and physical, has always been seen as the enemy of morality. However, there are much bigger enemies of our students’ collective moral fabric in Pakistani universities, than the non-existence of dupattas and chadars.

University experience should supplemented with a moral education that sees freedom not as an enemy, but as a means of motivating our youth

An average Pakistani university student goes through those four years witnessing gross ethical violations on campus ranging from blatant gender disparity and everyday harassment of female students, to severely underpaid and ill-treated janitorial and custodial staff. Additionally, our youth observe and internalise the visible discrimination minority students face, and the growing atmosphere of intolerance and aversion to debate, dialogue and open thinking. Yet, none of these issues appear on the list of ‘moral correction’ we’d like to subject our campuses to.

It is shocking that one of Pakistan’s top universities just recently hosted its first ever cultural night with music and dance, as a four-decade-old dictatorship of fundamentalist student groups is waning. Are the students who will now watch music and dance on PU’s campus more likely to be morally corrupt, or were those who were socialised during the 40 years of religious intolerance and violent mafias? Similarly, are the students who witness the slave-like conditions in which campus support staff reside not likely to reciprocate those attitudes in their homes and workplaces?

The question is larger than whether our university campuses should espouse Islamic values or uphold cultural ideals. The real question is why our cultural or religious identity feels more threatened by music, dance, liberal dresses, or male-female interaction on campuses, than it does by the complete denial of a fair and just education system. Is it not worse for the ethical values of our youth to witness violent stabbings of teachers, or the shameful treatment of ethnic minority and working class students? But the administrations and their keyboard warriors, who rejoice at the decision to make girls wear burqas in schools and universities, hardly ever use the same energy to raise their voices against harassment on campus, or unfair fee hikes, or the treatment of minority students. Pakistan is a case study in misplaced priorities where we fear open-minded thinking much more than we fear intolerance justified on the basis of religion, ethnicity, class and gender. By reciprocating the same attitudes within our student body, we are producing yet another generation of Pakistanis who can standby as a mob lynches the life out of a student accused of blasphemy.

A fundamental way in which universities differ from schools across the world is in the provision of the freedom of thought, mobility and action. This should be supplemented with a moral education that sees freedom not as an enemy, but as a means of motivating our youth to be able to have more avenues and choices and to advocate more vehemently for new ideas. It would do us justice to focus on providing a moral education to our students that prioritizes equality, tolerance, and social responsibility. This moral education should build a sense of empathy in our students for those who are from a different walk of life, and tolerance for those who might have fundamentally different points of view. Rather than caging students of different genders, it must build bridges between male and female students. It is time to shift our priorities from the lengths of a kameez, to a deeper understanding of gender equality and harassment, from the ban on cultural and musical festivities, to a metamorphosis of different cultures and ethnicities on campus and from the limitations on freedom of speech, to equipping them with the courage to raise their voices.

The writer is an entrepreneur and a women’s rights advocate. She can be reached on Twitter @nayabGJan