Taxation has an interesting relationship with the Pakistani public. While the government has trouble trying to collect taxes, debt has gotten worse because people either evade taxes, or don’t trust the government.

A new set of reports by Research and Advocacy for the Advancement of Allied Reforms (RAFTAAR), include crucial data on how public expenditure, along with existential problems that have resulted from low levels of tax revenue along with the solutions that have gone on ignored.

RAFTAAR gathered its data in part through collaboration with the Consortium For Development Policy Research (CDPR), while the research team was led by Dr. Hamid Mukhtar.

The reports highlight some interesting contradictions. Pakistani people almost always rank high when it comes to surveys that highlight how patriotic the people in the country are. However, when it comes to translate patriotism into pragmatism a great disparity makes itself obvious.

Only 0.3 per cent or 500,000 people in the country file their income tax returns, according to the report. This is in contrast to India that has around 27 million people filing returns, i.e. three per cent of its population.

It is no wonder that Pakistan’s tax to GDP ratio is only 9.4 per cent placing it at the bottom of revenue generation globally. Pakistanis also suffer from various misconceptions about the debt that they are in. Foreign debt is often viewed with suspicion and disdain. “Pakistan’s public debt was 63 per cent of GDP in 2014, of which a large majority is domestic debt. Contrary to popular belief, this domestic debt is substantially more expensive than foreign debt,” RAFTAAR’s Public Expenditure report points out.

Moreover, despite the fact that many do not pay their taxes, they do enjoy several subsidies. “Federal government’s expenditure on subsidies and grants… has increased rapidly in the past few years, from 1 per cent of GDP in 2002 to more than 2.5 per cent in 2014,” the report highlights.

Additionally the government continues to suffer from a grand predicament when it comes to how it handles its money. “… 29 per cent of the [federal government’s expenditure] is allocated towards subsidies and grants. These expenses either cannot or are unlikely to be decreased in the short run,” the report outlines.

“Consequently, development expenditure as a per cent of GDP has fallen sharply in the past 30 years,”

On a global scale there is a worldwide crisis in terms of refugees and donor fatigue’s impact has been felt in terms of development projects, not just in Pakistan but around the world. Moreover, during the last eight years only about 15 per cent of the overall development in the country was financed through foreign assistance. It accounted for less than four per cent of total expenditures.

The country’s development expenditure was ironically higher during the FY85-89 period at 5.5 per cent, as compared to now i.e. 3.2 per cent. The only spike it witnessed was during the FY05-09 period, apart from which it has consistently dwindled down. The very fact that a developing country has quite literally stopped focusing on development is alarming.

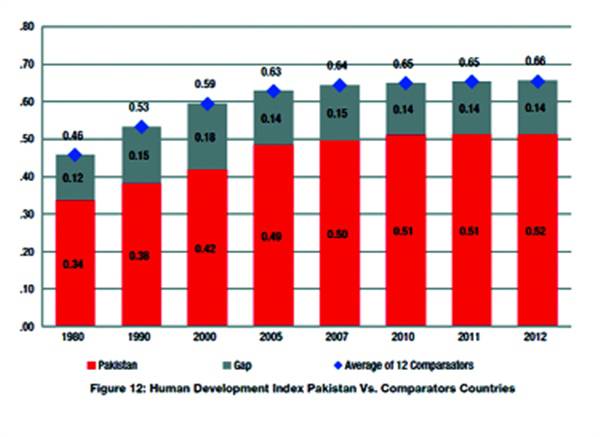

Figure 12 of the report indicates that our status in terms of the human development index is also nothing to be proud of. “Pakistan’s key social indicators remain among the worst in the region; and some of these indicators puts Pakistan in the company of sub-Saharan countries,” the report indicates.

“Pakistan’s primary school (net) enrolment rate is almost 21 bps below that of its comparators; life expectancy at birth lags 6 years behind; and infant mortality rate is more than 2.5 times that of comparators. Pakistan’s poor human development not only indicates weak social development, but also points to low overall productivity of Pakistan’s labour force,” it goes on to explain.

Development sectors often do not get adequate finances which result in such a scenario. The report highlights that these sectors have been “perpetually underfinanced, indicating the low priority these sectors have held for the policy-makers of the country.”

Even when provisions were made for these sectors the impact was not what it should have or could have been. “To assess the adequacy of social spending, it is important to note the Seventh NFC Award sharply increased the share of province in federal revenue. This led to a marked increase in spending on health and education (at 19.4% p.a. between 2005/06 and 2013/14),” the report states, only to follow it up with the fact that most of the increase was eaten up because of the high inflation that has plagued the country. “[As a result] real inputs devoted towards these sectors increased at a much smaller rate (9.1 percent per annum.)” it observed.

Evasion of taxes isn’t that easy to pin onto the people as well. The report highlights that development programs “remain the most potent tool for the line ministries to expand their claim on fiscal resources…” That would ordinarily translate into more money for development and ergo more development as well.

However, in Pakistan things are done a little differently. A World Bank study determined that a development project will typically take twice the money and twice the time to be executed. And the final product may have several chinks in its armour when it is completed.

Low tax collection has resulted in the debt burden entering into crisis mode. Interest payments are eating up almost half of our tax revenue at 44 per cent, amounting to over Rs. 6,684 interest paid per citizen.

Former principal economic advisor of the Ministry of Finance Sakib Sherani feels that without taxation Pakistan will continue to deepen its existential crisis. “People think other issues are bigger, but for a state, not being able to collect taxes is a fundamental issue,” he said.

Sherani also explained how the government can help get people on board, apart from revamping policy.

“These are two or three aspects to this; the government has to show that is spending the money in the right places. Right now we are not getting that feeling as citizens,” he said.

“The second aspect is that it is a bit of an excuse on our parts. It is a bit of a rich argument because many people use many amenities that are provided for by taxes. I have had people come into my office in land cruisers driven on public roads that were paid for through taxes!” he said.

Sherani pointed out that while the situation has become progressively worse since the 90s, in the past Pakistani were getting a bang for their buck as taxes did translate into a lot of value for money. “The report has given examples of this as well, of the big projects that have been executed as well and continue to be used,” he said.

“To say that no value or money has been delivered is incorrect. Many people who can afford to pay taxes are utilising services in every way but they are not willing to cough up their due share,” he lamented.

The third element of the equation revolved around the need for the government to also demonstrate equity and fairness on how they collect taxes. “I need to be sure that it’s not just you or me that’s just paying taxes but that everybody is paying taxes,” Sherani explained. This would mean that the public would have the surety that some people are not getting undue exemptions based on any bias or favour.

“Tax itself is a powerful message that they need to communicate,” Sherani asserted.

A new set of reports by Research and Advocacy for the Advancement of Allied Reforms (RAFTAAR), include crucial data on how public expenditure, along with existential problems that have resulted from low levels of tax revenue along with the solutions that have gone on ignored.

RAFTAAR gathered its data in part through collaboration with the Consortium For Development Policy Research (CDPR), while the research team was led by Dr. Hamid Mukhtar.

The reports highlight some interesting contradictions. Pakistani people almost always rank high when it comes to surveys that highlight how patriotic the people in the country are. However, when it comes to translate patriotism into pragmatism a great disparity makes itself obvious.

Only 0.3 per cent or 500,000 people in the country file their income tax returns, according to the report. This is in contrast to India that has around 27 million people filing returns, i.e. three per cent of its population.

The fact that a developing country has stopped focusing on development is alarming

It is no wonder that Pakistan’s tax to GDP ratio is only 9.4 per cent placing it at the bottom of revenue generation globally. Pakistanis also suffer from various misconceptions about the debt that they are in. Foreign debt is often viewed with suspicion and disdain. “Pakistan’s public debt was 63 per cent of GDP in 2014, of which a large majority is domestic debt. Contrary to popular belief, this domestic debt is substantially more expensive than foreign debt,” RAFTAAR’s Public Expenditure report points out.

Moreover, despite the fact that many do not pay their taxes, they do enjoy several subsidies. “Federal government’s expenditure on subsidies and grants… has increased rapidly in the past few years, from 1 per cent of GDP in 2002 to more than 2.5 per cent in 2014,” the report highlights.

Additionally the government continues to suffer from a grand predicament when it comes to how it handles its money. “… 29 per cent of the [federal government’s expenditure] is allocated towards subsidies and grants. These expenses either cannot or are unlikely to be decreased in the short run,” the report outlines.

“Consequently, development expenditure as a per cent of GDP has fallen sharply in the past 30 years,”

On a global scale there is a worldwide crisis in terms of refugees and donor fatigue’s impact has been felt in terms of development projects, not just in Pakistan but around the world. Moreover, during the last eight years only about 15 per cent of the overall development in the country was financed through foreign assistance. It accounted for less than four per cent of total expenditures.

The country’s development expenditure was ironically higher during the FY85-89 period at 5.5 per cent, as compared to now i.e. 3.2 per cent. The only spike it witnessed was during the FY05-09 period, apart from which it has consistently dwindled down. The very fact that a developing country has quite literally stopped focusing on development is alarming.

Figure 12 of the report indicates that our status in terms of the human development index is also nothing to be proud of. “Pakistan’s key social indicators remain among the worst in the region; and some of these indicators puts Pakistan in the company of sub-Saharan countries,” the report indicates.

“Pakistan’s primary school (net) enrolment rate is almost 21 bps below that of its comparators; life expectancy at birth lags 6 years behind; and infant mortality rate is more than 2.5 times that of comparators. Pakistan’s poor human development not only indicates weak social development, but also points to low overall productivity of Pakistan’s labour force,” it goes on to explain.

Development sectors often do not get adequate finances which result in such a scenario. The report highlights that these sectors have been “perpetually underfinanced, indicating the low priority these sectors have held for the policy-makers of the country.”

Even when provisions were made for these sectors the impact was not what it should have or could have been. “To assess the adequacy of social spending, it is important to note the Seventh NFC Award sharply increased the share of province in federal revenue. This led to a marked increase in spending on health and education (at 19.4% p.a. between 2005/06 and 2013/14),” the report states, only to follow it up with the fact that most of the increase was eaten up because of the high inflation that has plagued the country. “[As a result] real inputs devoted towards these sectors increased at a much smaller rate (9.1 percent per annum.)” it observed.

Evasion of taxes isn’t that easy to pin onto the people as well. The report highlights that development programs “remain the most potent tool for the line ministries to expand their claim on fiscal resources…” That would ordinarily translate into more money for development and ergo more development as well.

However, in Pakistan things are done a little differently. A World Bank study determined that a development project will typically take twice the money and twice the time to be executed. And the final product may have several chinks in its armour when it is completed.

Low tax collection has resulted in the debt burden entering into crisis mode. Interest payments are eating up almost half of our tax revenue at 44 per cent, amounting to over Rs. 6,684 interest paid per citizen.

Former principal economic advisor of the Ministry of Finance Sakib Sherani feels that without taxation Pakistan will continue to deepen its existential crisis. “People think other issues are bigger, but for a state, not being able to collect taxes is a fundamental issue,” he said.

Sherani also explained how the government can help get people on board, apart from revamping policy.

“These are two or three aspects to this; the government has to show that is spending the money in the right places. Right now we are not getting that feeling as citizens,” he said.

“The second aspect is that it is a bit of an excuse on our parts. It is a bit of a rich argument because many people use many amenities that are provided for by taxes. I have had people come into my office in land cruisers driven on public roads that were paid for through taxes!” he said.

Sherani pointed out that while the situation has become progressively worse since the 90s, in the past Pakistani were getting a bang for their buck as taxes did translate into a lot of value for money. “The report has given examples of this as well, of the big projects that have been executed as well and continue to be used,” he said.

“To say that no value or money has been delivered is incorrect. Many people who can afford to pay taxes are utilising services in every way but they are not willing to cough up their due share,” he lamented.

The third element of the equation revolved around the need for the government to also demonstrate equity and fairness on how they collect taxes. “I need to be sure that it’s not just you or me that’s just paying taxes but that everybody is paying taxes,” Sherani explained. This would mean that the public would have the surety that some people are not getting undue exemptions based on any bias or favour.

“Tax itself is a powerful message that they need to communicate,” Sherani asserted.