The situation in eastern Ladakh is on a knife-edge. The prospect of deescalation between China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) troops and the Indian Army (IA) has grown very dim since the preemptive action by Indian troops to secure unoccupied heights on the south bank of Pangong Tso, a high-altitude lake, on the intervening night of August 29/30.

This is the first proactive action undertaken by IA since tensions flared up at the Line of Actual Control in the Ladakh theatre in the first week of May this year.

The action, however, has raised the temperature in the area. Reports that IA used elements of Special Frontier Force, a little-known and talked about outfit, has likely further complicated the situation. The SFF, reportedly, is a special operations unit whose officers and men are drawn from the exiled Tibetan community that lives in India since the Dalai Lama escaped to India in 1959.

The SFF units, according to Indian media reports, have trained paratroopers meant to be deployed behind PLA lines in Tibet in case of hostilities. While they haven’t been used in that role up until now, their employment in a preemptive operation against PLA troops in Ladakh flies in the face of India’s 2003 recognition of Tibet as part of China. That’s not a signal that would be lost on China.

A meeting between defence ministers of India and China on September 4 failed to resolve the issues on the ground. India’s defence minister Rajnath Singh and China’s General Wei Fenghe had met on the sidelines of a Shanghai Cooperation Organisation’s defence chiefs ministerial. This was the first high-level meet between the two sides since tensions began in May this year. No details were given by either side, which was a clear signal that both had stuck to their guns. This was also clear from reported remarks made by Gen Fenghe and Singh, both of whom talked tough.

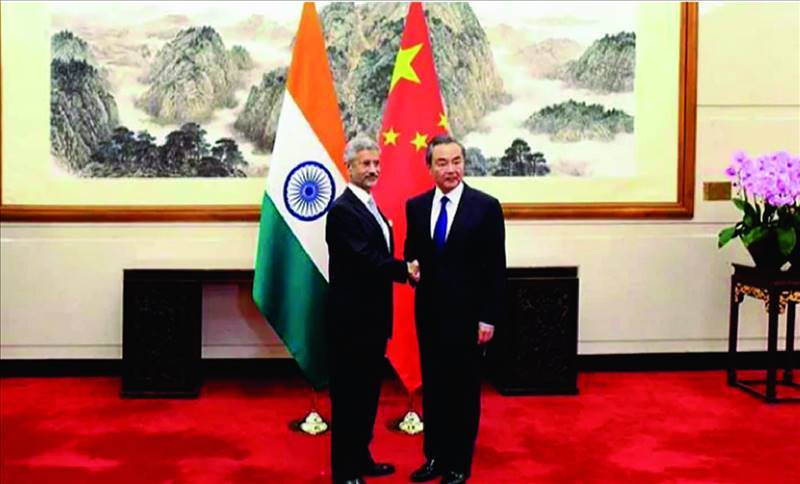

The only hope, albeit very slender, that the two sides might pull back from the brink is attached with the Thursday meeting between the Indian and Chinese foreign ministers on the sidelines of the SCO foreign ministers meeting. S. Jaishankar and Wang Yi will have a bilateral to work out some modus vivendi.

While Jaishankar, a very seasoned diplomat, has been insisting in interviews that the only solution can and must be through diplomacy, he has also made clear that the situation on the ground is very serious. With reference to the ground situation he is right and that is where it is difficult to see how he and Wang Yi could work out a solution. Consider.

While everyone talks about tensions at the LAC, the LAC itself is the problem in Ladakh. Where exactly is that line? India’s contention that the line is known is not borne out by historical facts, including developments that led to the 1962 War and saw Indian forces routed. Before that war, China had proposed that India accept China’s claim in Ladakh and then-Peking would accept a settlement in the eastern sector. As many authors have noted, this was dismissed by then-Indian prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. This tradeoff remained China’s position until the 1980s. That is no longer the case. China now includes the Tawang area in the eastern sector as part of China and insists on its 1959 claim line in the western sector.

China is also in no hurry to settle the issue with India for a simple reason: an un-demarcated line keeps India under pressure. I have already written elsewhere about the factors leading to the current standoff so I shan’t repeat them. But it’s important to note that there’s no single factor responsible for China’s current strategy. The strategy is driven by a medley of factors.

The other issue that makes it difficult for one to think that the odds might be in favour of a deescalation relates to the situation on the ground. The IA — as also the Indian media and public opinion — is already patting itself on the back for its preemptive action on a 30-km frontage. That self-congratulatory stance is both early and naive. The PLA has dominated the theatre both physically and psychologically until now. It simply cannot afford to let IA get out of that psychological bind. The psychological dominance in such contests is always a notch above the physical one.

Translated, it means that unless India agrees to vacate the heights its troops have occupied without a quid pro quo, PLA must deliver a riposte in that area or at other points in the theatre to restore psychological dominance in the theatre.

China is also the stronger state in this contest. For Beijing to agree to an outcome that puts New Delhi on an equal footing with it will be a big no. In fact, it will amount to China handing India a win. Put another way, if India has to win, it can’t be through diplomatic chinwagging; it must do so on the ground. And that’s where it must contend with the PLA.

That said, China’s strategy so far has been to dominate and direct India’s posture without a war. This is a strategy of compellence without resorting to actual use of force. It hinges, necessarily, on China’s psychological dominance. Also, as a stronger power, China wants to set the terms of engagement. That’s a lesson of history. India does this — or tries to — with all its neighbours. But this, paradoxically, makes it more difficult for China to take IA’s initiative lying down. In other words, this complicates the situation Jaishankar and Wang Yi are contending with, i.e., to find a diplomatic way out of the crisis.

There’s yet another problem. For China, the Ladakh crisis is not about controlling a barren stretch of land. How it deals with India is a strategic issue that has broader ramifications both in terms of power projection as well as China-US relations and Washington’s efforts to countervail China by getting India into the US camp.

Russia is playing a quiet role to mediate the problem. But it is difficult to see how Moscow can reconcile the asymmetries in the positions of both sides. This is a classic structural problem. Neither side, right earnestly, wants a war and yet both have demands that simply don’t have any points of convergence.

This piece was written before the Jaishankar-Wang Yi meet. Things might turn out differently if both foreign ministers could work out some magic formula to defuse the situation. But it will be difficult to play against so many odds. If this bilateral meeting meets the same fate as the defence ministers’ meeting, PLA’s riposte will be inevitable. That it will move in the Chushul sub-sector is unlikely. PLA troops have physical advantages at various other points in the theatre. They could go for horizontal escalation at multiple points. It will be interesting to see how the situation pans out in the next few days.

The writer is a former News Editor of The Friday Times. He reluctantly tweets @ejazhaider

This is the first proactive action undertaken by IA since tensions flared up at the Line of Actual Control in the Ladakh theatre in the first week of May this year.

The action, however, has raised the temperature in the area. Reports that IA used elements of Special Frontier Force, a little-known and talked about outfit, has likely further complicated the situation. The SFF, reportedly, is a special operations unit whose officers and men are drawn from the exiled Tibetan community that lives in India since the Dalai Lama escaped to India in 1959.

The SFF units, according to Indian media reports, have trained paratroopers meant to be deployed behind PLA lines in Tibet in case of hostilities. While they haven’t been used in that role up until now, their employment in a preemptive operation against PLA troops in Ladakh flies in the face of India’s 2003 recognition of Tibet as part of China. That’s not a signal that would be lost on China.

A meeting between defence ministers of India and China on September 4 failed to resolve the issues on the ground. India’s defence minister Rajnath Singh and China’s General Wei Fenghe had met on the sidelines of a Shanghai Cooperation Organisation’s defence chiefs ministerial. This was the first high-level meet between the two sides since tensions began in May this year. No details were given by either side, which was a clear signal that both had stuck to their guns. This was also clear from reported remarks made by Gen Fenghe and Singh, both of whom talked tough.

The only hope, albeit very slender, that the two sides might pull back from the brink is attached with the Thursday meeting between the Indian and Chinese foreign ministers on the sidelines of the SCO foreign ministers meeting. S. Jaishankar and Wang Yi will have a bilateral to work out some modus vivendi.

While Jaishankar, a very seasoned diplomat, has been insisting in interviews that the only solution can and must be through diplomacy, he has also made clear that the situation on the ground is very serious. With reference to the ground situation he is right and that is where it is difficult to see how he and Wang Yi could work out a solution. Consider.

While everyone talks about tensions at the LAC, the LAC itself is the problem in Ladakh. Where exactly is that line? India’s contention that the line is known is not borne out by historical facts, including developments that led to the 1962 War and saw Indian forces routed. Before that war, China had proposed that India accept China’s claim in Ladakh and then-Peking would accept a settlement in the eastern sector. As many authors have noted, this was dismissed by then-Indian prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru. This tradeoff remained China’s position until the 1980s. That is no longer the case. China now includes the Tawang area in the eastern sector as part of China and insists on its 1959 claim line in the western sector.

China is also in no hurry to settle the issue with India for a simple reason: an un-demarcated line keeps India under pressure. I have already written elsewhere about the factors leading to the current standoff so I shan’t repeat them. But it’s important to note that there’s no single factor responsible for China’s current strategy. The strategy is driven by a medley of factors.

The other issue that makes it difficult for one to think that the odds might be in favour of a deescalation relates to the situation on the ground. The IA — as also the Indian media and public opinion — is already patting itself on the back for its preemptive action on a 30-km frontage. That self-congratulatory stance is both early and naive. The PLA has dominated the theatre both physically and psychologically until now. It simply cannot afford to let IA get out of that psychological bind. The psychological dominance in such contests is always a notch above the physical one.

Translated, it means that unless India agrees to vacate the heights its troops have occupied without a quid pro quo, PLA must deliver a riposte in that area or at other points in the theatre to restore psychological dominance in the theatre.

China is also the stronger state in this contest. For Beijing to agree to an outcome that puts New Delhi on an equal footing with it will be a big no. In fact, it will amount to China handing India a win. Put another way, if India has to win, it can’t be through diplomatic chinwagging; it must do so on the ground. And that’s where it must contend with the PLA.

That said, China’s strategy so far has been to dominate and direct India’s posture without a war. This is a strategy of compellence without resorting to actual use of force. It hinges, necessarily, on China’s psychological dominance. Also, as a stronger power, China wants to set the terms of engagement. That’s a lesson of history. India does this — or tries to — with all its neighbours. But this, paradoxically, makes it more difficult for China to take IA’s initiative lying down. In other words, this complicates the situation Jaishankar and Wang Yi are contending with, i.e., to find a diplomatic way out of the crisis.

There’s yet another problem. For China, the Ladakh crisis is not about controlling a barren stretch of land. How it deals with India is a strategic issue that has broader ramifications both in terms of power projection as well as China-US relations and Washington’s efforts to countervail China by getting India into the US camp.

Russia is playing a quiet role to mediate the problem. But it is difficult to see how Moscow can reconcile the asymmetries in the positions of both sides. This is a classic structural problem. Neither side, right earnestly, wants a war and yet both have demands that simply don’t have any points of convergence.

This piece was written before the Jaishankar-Wang Yi meet. Things might turn out differently if both foreign ministers could work out some magic formula to defuse the situation. But it will be difficult to play against so many odds. If this bilateral meeting meets the same fate as the defence ministers’ meeting, PLA’s riposte will be inevitable. That it will move in the Chushul sub-sector is unlikely. PLA troops have physical advantages at various other points in the theatre. They could go for horizontal escalation at multiple points. It will be interesting to see how the situation pans out in the next few days.

The writer is a former News Editor of The Friday Times. He reluctantly tweets @ejazhaider